Uncovering Hope and Resilience Through Heavy Music.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: a Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: A Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A. Johnson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC LOGGING SONGS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST: A STUDY OF THREE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS By LESLIE A. JOHNSON A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Leslie A. Johnson defended on March 28, 2007. _____________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ` _____________________________ Karyl Louwenaar-Lueck Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have helped me with this manuscript and my academic career: my parents, grandparents, other family members and friends for their support; a handful of really good teachers from every educational and professional venture thus far, including my committee members at The Florida State University; a variety of resources for the project, including Dr. Jens Lund from Olympia, Washington; and the subjects themselves and their associates. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

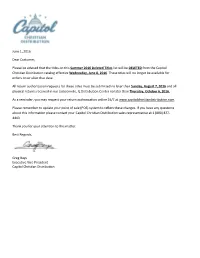

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please Be Advised That the Titles On

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please be advised that the titles on this Summer 2016 Deleted Titles list will be DELETED from the Capitol Christian Distribution catalog effective Wednesday, June 8, 2016. These titles will no longer be available for orders on or after that date. All return authorization requests for these titles must be submitted no later than Sunday, August 7, 2016 and all physical returns received in our Jacksonville, IL Distribution Center no later than Thursday, October 6, 2016. As a reminder, you may request your return authorization online 24/7 at www.capitolchristiandistribution.com. Please remember to update your point of sale (POS) system to reflect these changes. If you have any questions about this information please contact your Capitol Christian Distribution sales representative at 1 (800) 877- 4443. Thank you for your attention to this matter. Best Regards, Greg Bays Executive Vice President Capitol Christian Distribution CAPITOL CHRISTIAN DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2016 DELETED TITLES LIST Return Authorization Due Date August 7, 2016 • Physical Returns Due Date October 6, 2016 RECORDED MUSIC ARTIST TITLE UPC LABEL CONFIG Amy Grant Amy Grant 094639678525 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant My Father's Eyes 094639678624 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Never Alone 094639678723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Straight Ahead 094639679225 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Unguarded 094639679324 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant House Of Love 094639679829 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Behind The Eyes 094639680023 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant A Christmas To Remember 094639680122 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Simple Things 094639735723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Icon 5099973589624 Amy Grant Productions CD Seventh Day Slumber Finally Awake 094635270525 BEC Recordings CD Manafest Glory 094637094129 BEC Recordings CD KJ-52 The Yearbook 094637829523 BEC Recordings CD Hawk Nelson Hawk Nelson Is My Friend 094639418527 BEC Recordings CD The O.C. -

Культура І Мистецтво Великої Британії Culture and Art of Great Britain

НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИХ НАУК УКРАЇНИ ІНСТИТУТ ПЕДАГОГІКИ Т.К. Полонська КУЛЬТУРА І МИСТЕЦТВО ВЕЛИКОЇ БРИТАНІЇ CULTURE AND ART OF GREAT BRITAIN Навчальний посібник елективного курсу з англійської мови для учнів старших класів профільної школи Київ Видавничий дім «Сам» 2017 УДК 811.111+930.85(410)](076.6) П 19 Рекомендовано до друку вченою радою Інституту педагогіки НАПН України (протокол №11 від 08.12.2016 року) Схвалено для використання у загальноосвітніх навчальних закладах (лист ДНУ «Інститут модернізації змісту освіти». №21.1/12 -Г-233 від 15.06.2017 року) Рецензенти: Олена Ігорівна Локшина – доктор педагогічних наук, професор, завідувачка відділу порівняльної педагогіки Інституту педагогіки НАПН України; Світлана Володимирівна Соколовська – кандидат педагогічних наук, доцент, заступник декана з науково- методичної та навчальної роботи факультету права і міжнародних відносин Київського університету імені Бориса Грінченка; Галина Василівна Степанчук – учителька англійської мови Навчально-виховного комплексу «Нововолинська спеціалізована школа І–ІІІ ступенів №1 – колегіум» Нововолинської міської ради Волинської області. Культура і мистецтво Великої Британії : навчальний посібник елективного курсу з англійської мови для учнів старших класів профільної школи / Т. К. Полонська. – К. : Видавничий дім «Сам», 2017. – 96 с. ISBN Навчальний посібник є основним засобом оволодіння учнями старшої школи змістом англомовного елективного курсу «Культура і мистецтво Великої Британії». Створення посібника сприятиме подальшому розвиткові у -

Heavy Metal and Classical Literature

Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 ROCKING THE CANON: HEAVY METAL AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE By Heather L. Lusty University of Nevada, Las Vegas While metalheads around the world embrace the engaging storylines of their favorite songs, the influence of canonical literature on heavy metal musicians does not appear to have garnered much interest from the academic world. This essay considers a wide swath of canonical literature from the Bible through the Science Fiction/Fantasy trend of the 1960s and 70s and presents examples of ways in which musicians adapt historical events, myths, religious themes, and epics into their own contemporary art. I have constructed artificial categories under which to place various songs and albums, but many fit into (and may appear in) multiple categories. A few bands who heavily indulge in literary sources, like Rush and Styx, don’t quite make my own “heavy metal” category. Some bands that sit 101 Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 on the edge of rock/metal, like Scorpions and Buckcherry, do. Other examples, like Megadeth’s “Of Mice and Men,” Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and Cradle of Filth’s “Nymphetamine” won’t feature at all, as the thematic inspiration is clear, but the textual connections tenuous.1 The categories constructed here are necessarily wide, but they allow for flexibility with the variety of approaches to literature and form. A segment devoted to the Bible as a source text has many pockets of variation not considered here (country music, Christian rock, Christian metal). -

Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition

Notes and Errata for Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition Nachum Dershowitz and Edward M. Reingold Cambridge University Press, 2008 4:00am, July 24, 2013 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] Cuiusvis hominis est errare; nullius nisi insipientis in errore perseverare. [Any man can make a mistake; only a fool keeps making the same one.] —Attributed to Marcus Tullius Cicero If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. -

A Survey of Christian Cross-Over Songwriting Core Principles and Potential for Impact

CHRISTIAN CROSS-OVER SONGWRITING 1 A Survey of Christian Cross-Over Songwriting Core Principles and Potential for Impact Paul Malhotra A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2013 CHRISTIAN CROSS-OVER SONGWRITING 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ John D. Kinchen III, D.M.A. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Michael Babcock, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Mr. Don Marsh, M.S. Committee Member ______________________________ Marilyn Gadomski, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Director ______________________________ Date CHRISTIAN CROSS-OVER SONGWRITING 3 Abstract A cross-over song has been defined as a song written by a Christian artist aimed at a mainstream audience. An understanding of the core principles of cross-over songs and their relevance in contemporary culture is essential for Christian songwriters. Six albums marked by spiritual overtones or undertones, representing a broad spectrum of contemporary cross-over music, were examined. Selected songs were critiqued by analyzing the album of origin, lyrical content, author’s expressed worldview, and level of commercial success. Renaissance art also provided a historical parallel to modern day songwriting. Recommendations were developed for Christian songwriters to craft songs with greater effectiveness to impact the culture while adhering to a biblical worldview. CHRISTIAN CROSS-OVER SONGWRITING 4 A Survey of Christian Cross-Over Songwriting An exploration of Christian cross-over music can provide an objective framework for evaluating songs and developing guidelines for Christian songwriters so they can enhance their effectiveness in communicating with their audiences. -

Auburn CV (MOLK)

Molk 1 DAVID MOLK 2190 E 11th Ave, Ap 521 Denver, CO 80206 (860) 966-3802 (cell) [email protected] www.molkmusic.com Education PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Princeton, NJ Ph.D Music Composition, July 2016 M.A. Music Composition, May 2013 • Dissertation: • Composition Component—softer shadows (percussion quartet for two vibraphones in two movements, 35 minutes) • Research Component: Classical Form in EDM: Ambiguities in BT’s This Binary Universe • Advisor: Dan Trueman • Composition Studies: Dan Trueman, Paul Lansky, Steven Mackey, Dmitri Tymoczko, Juri Seo, Donnacha Dennehy, Barbara White TUFTS UNIVERSITY, Medford, MA M.A. Music Composition, May 2011 • Thesis: String Quartet No. 1 (3 movements, 30 minutes) • Advisor: John McDonald • Composition Studies: John McDonald BERKLEE COLLEGE OF MUSIC, Boston, MA B.M. magna cum laude, Composition, December 2008 MIDDLEBURY COLLEGE, Middlebury, VT B.A. magna cum laude, Math and Economics, May 2004 • Honors Thesis: A Mathematical Survey of Game Theory: Games of Incomplete Information Significant Compositions loss, found—Vibraphone solo, premiere at Georgetown University with national release at PASIC 2018 Dreams—Percussion trio plus electronics, premiered at 2016 and performed at Friends University, Furman Univesity, Georgetown University, Princeton University, and venues in Quebec. murmur—Percussion quartet (two vibes), premiered at SoSI 2015 and subsequently performed by Sandbox Percussion, Sō Percussion, and students at University of Nebraska (Lincoln), Northern Illinois University, Ohio University, Salisbury, -

Solution 6: Drag and Drop 169

06_0132344815_ch06.qxd 10/16/07 11:41 AM Page 167 SolutionSolution 1: Drag and Drop 167 6 Drag and Drop The ultimate in user interactivity, drag and drop is taken for granted in desktop appli- cations but is a litmus test of sorts for web applications: If you can easily implement drag and drop with your web application framework, then you know you’ve got something special. Until now, drag and drop for web applications has, for the most part, been limited to specialized JavaScript frameworks such as Script.aculo.us and Rico.1 No more. With the advent of GWT, we have drag-and-drop capabilities in a Java-based web applica- tion framework. Although GWT does not explicitly support drag and drop (drag and drop is an anticipated feature in the future), it provides us with all the necessary ingre- dients to make our own drag-and-drop module. In this solution, we explore drag-and-drop implementation with GWT. We implement drag and drop in a module of its own so that you can easily incorporate drag and drop into your applications. Stuff You’re Going to Learn This solution explores the following aspects of GWT: • Implementing composite widgets with the Composite class (page 174) • Removing widgets from panels (page 169) • Changing cursors for widgets with CSS styles (page 200) • Implementing a GWT module (page 182) • Adding multiple listeners to a widget (page 186) • Using the AbsolutePanel class to place widgets by pixel location (page 211) • Capturing and releasing events for a specific widget (page 191) • Using an event preview to inhibit browser reactions to events (page 196) 1 See http://www.script.aculo.us and http://openrico.org for more information about Script.aculo.us and Rico, respectively. -

Thomas Dolby: the Sole Inhabitant Story and Photos by John Voket Thomas Dolby Returns He Wants for the Rest of His Natural Life

InterMixx • Independent Music Magazine • • InterMixx • Independent Music Magazine InterMixx • Independent Music Magazine • Officer Roseland: Rock Juggernaut WHY THE BAND SIMPLY CANNOT BE STOPPED Officer Roseland has been a rock band for 5 R o s e l a n d the Independent film festival, we rented a van and drove out years. However, it has taken them that long claims with Music Conference to Park City, Utah to promote our asses off. to find a “stable” (I use this term loosely) certitude that in August and lineup. Two of three original members they cannot be S e p t e m b e r InterMixx: Did you already make the music remain with the band: Dan Daidone and stopped. Read of ‘06, the band video, what song is it for, when can we Brian Jones. When the band started out on for even was asked expect it, and where will it be available? as a 3 piece with Daidone on vocals and more proof... a few quick OR: We are in pre-production right now bass, Jones was playing keyboards and questions... and it will be for the song “Wrist Bizness.” guitars and Matt Pone played drums. While Over the next We’d like to have it available by late recording their first release, they decided two and one half I n t e r M i x x : winter or early spring, depending on what that in order to put on a great, energetic, years the band What did you Punxatawny Phil has to report. We’ll have live performance, they would need Dan to would audition think about the it on our website, on Youtube, MySpace, focus exclusively on vocals and therefore thirty-seven IMC? What and hopefully DirecTV. -

Exploring the Chinese Metal Scene in Contemporary Chinese Society (1996-2015)

"THE SCREAMING SUCCESSOR": EXPLORING THE CHINESE METAL SCENE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE SOCIETY (1996-2015) Yu Zheng A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2016 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2016 Yu Zheng All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This research project explores the characteristics and the trajectory of metal development in China and examines how various factors have influenced the localization of this music scene. I examine three significant roles – musicians, audiences, and mediators, and focus on the interaction between the localized Chinese metal scene and metal globalization. This thesis project uses multiple methods, including textual analysis, observation, surveys, and in-depth interviews. In this thesis, I illustrate an image of the Chinese metal scene, present the characteristics and the development of metal musicians, fans, and mediators in China, discuss their contributions to scene’s construction, and analyze various internal and external factors that influence the localization of metal in China. After that, I argue that the development and the localization of the metal scene in China goes through three stages, the emerging stage (1988-1996), the underground stage (1997-2005), the indie stage (2006-present), with Chinese characteristics. And, this localized trajectory is influenced by the accessibility of metal resources, the rapid economic growth, urbanization, and the progress of modernization in China, and the overall development of cultural industry and international cultural communication. iv For Yisheng and our unborn baby! v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to show my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00