Forgotten British Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magic Christian on Talking Pictures TV Directed by Joseph Mcgrath in 1969

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Mon 6th April 2020 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 The Magic Christian on Talking Pictures TV Directed by Joseph McGrath in 1969. Stars: Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr, with appearances by Raquel Welch, John Cleese, Graham Chapman, Spike Milligan, Christopher Lee, Richard Attenborough and Roman Polanski. Sir Guy Grand is the richest man in the world, and when he stumbles across a young orphan in the park he decides to adopt him and travel around the world spending cash. It’s not long before the two of them discover on their happy-go-lucky madcap escapades that money does, in fact, buy anything you want. Airs on Saturday 11th April at 9pm Monday 6th April 08:55am Wednesday 8th April 3:45pm Thunder Rock (1942) Heart of a Child (1958) Supernatural drama directed by Roy Drama, directed by Clive Donner. Boulting. Stars: Michael Redgrave, Stars: Jean Anderson, Barbara Mullen and James Mason. Donald Pleasence, Richard Williams. One of the Boulting Brothers’ finest, A young boy is forced to sell the a writer disillusioned by the threat of family dog to pay for food. Will his fascism becomes a lighthouse keeper. canine friend find him when he is trapped in a snowstorm? Monday 6th April 10pm The Family Way (1966) Wednesday 8th April 6:20pm Drama. Directors: Rebecca (1940) Roy and John Boulting. Mystery, directed by Alfred Hitchcock Stars: Hayley Mills, Hywel Bennett and starring Laurence Olivier, John Mills and Marjorie Rhodes. Joan Fontaine and George Sanders. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

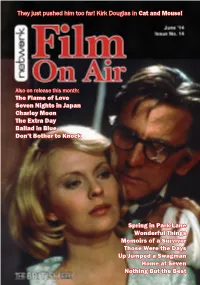

Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! the Flame of Love

They just pushed him too far! Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! Also on release this month: The Flame of Love Seven Nights in Japan Charley Moon The Extra Day Ballad in Blue Don’t Bother to Knock Spring in Park Lane Wonderful Things Memoirs of a Survivor Those Were the Days Up Jumped a Swagman Home at Seven Nothing But the Best Julie Christie stars in an award-winning adaptation of Doris Lessing’s famous dystopian novel. This complex, haunting science-fiction feature is presented in a Set in the exotic surroundings of Russia before the First brand-new transfer from the original film elements in World War, The Flame of Love tells the tragic story of the its as-exhibited theatrical aspect ratio. doomed love between a young Chinese dancing girl and the adjutant to a Russian Grand Duke. One of five British films Set in Britain at an unspecified point in the near- featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, The future, Memoirs of a Survivor tells the story of ‘D’, a Flame of Love (also known as Hai-Tang) was the star’s first housewife trying to carry on after a cataclysmic war ‘talkie’, made during her stay in London in the early 1930s, that has left society in a state of collapse. Rubbish is when Hollywood’s proscription of love scenes between piled high in the streets among near-derelict buildings Asian and Caucasian actors deprived Wong of leading roles. covered with graffiti; the electricity supply is variable, and water is now collected from a van. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Screenwriting CONOR Publish

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.4324/9780203080771 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Conor, B. (2014). Screenwriting: Creative labor and professional practice. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203080771 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Porträt : Antwort Einer Mutigen Frau

Porträt : Antwort einer mutigen Frau Autor(en): Silberschmidt, Catherine Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Filmbulletin : Zeitschrift für Film und Kino Band (Jahr): 60 (2018) Heft 374 PDF erstellt am: 29.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-863035 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Holyday Camp (1947) To Dorothy a Son (1954) Porträt wie intelligente Antwort auf die der Starpianistin Francesca und Geschlechterstereotype des konservativen ihrem Vormund, einem zwanghaften, britischen Nachkriegsfilms. latent homosexuellen Frauenhasser, Fasziniert von amerikanischen der sein Mündel zu Höchstleistungen Slapstickkomödien, die sie als Kind antreibt und ihr Beziehungen zu Muriel Box war eine der im Dorfkino gesehen hatte, entstand andern Männern untersagt. -

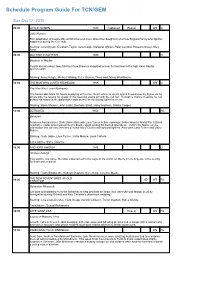

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GEM Sun Oct 17, 2010 06:00 LITTLE WOMEN 1949 Captioned Repeat WS G Little Women Film adaptation of Louisa May Alcott's beloved novel about four daughters of a New England family who fight for happiness during the Civil War. Starring: June Allyson, Elizabeth Taylor, Janet Leigh, Margaret O'brien, Peter Lawford, Rossano Brazzi, Mary Astor 08:30 MAYTIME IN MAYFAIR 1949 G Maytime In Mayfair Penniless man-about-town Michael Gore-Brown is delighted to hear he has been left a high-class Mayfair fashion salon. Starring: Anna Neagle, Michael Wilding, Peter Graves, Thora Hird, Mona Washbourne 10:35 THE MAN WHO LOVED REDHEADS 1955 WS G The Man Who Loved Redheads The honourable Mark St. Neots is playing with some chums when he meets and is bowled over by Sylvia. As he grows older he retains his image of this beautiful young girl with the red hair. Through a chance meeting, he can pursue his career in the diplomatic corps as well as the young ladies he meets. Starring: Moira Shearer, John Justin, Denholm Elliott, Harry Andrews, Gladys Cooper 12:40 BETRAYED 1954 PG Betrayed Academy Award winner Clark Gable stars with Lana Turner in this espionage thriller about a World War II Dutch resistance leader who must uncover a double agent among his trusted operatives... before the Nazis receive information that will cost the lives of hundreds of Dutch underground fighters. Also stars Lana Turner and Victor Mature. Starring: Clark Gable, Lana Turner, Victor Mature, Louis Calhern Cons.Advice: Some Violence 15:00 ANCHORS AWEIGH 1945 G Anchors Aweigh Two sailors, one naive, the other experienced in the ways of the world, on liberty in Los Angeles, is the setting for this movie musical. -

The Nation's Matron: Hattie Jacques and British Post-War Popular Culture

The Nation’s Matron: Hattie Jacques and British post-war popular culture Estella Tincknell Abstract: Hattie Jacques was a key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, condensing a range of contradictions around power, desire, femininity and class through her performances as a comedienne, primarily in the Carry On series of films between 1958 and 1973. Her recurrent casting as ‘Matron’ in five of the hospital-set films in the series has fixed Jacques within the British popular imagination as an archetypal figure. The contested discourses around nursing and the centrality of the NHS to British post-war politics, culture and identity, are explored here in relation to Jacques’s complex star meanings as a ‘fat woman’, ‘spinster’ and authority figure within British popular comedy broadly and the Carry On films specifically. The article argues that Jacques’s star meanings have contributed to nostalgia for a supposedly more equitable society symbolised by socialised medicine and the feminine authority of the matron. Keywords: Hattie Jacques; Matron; Carry On films; ITMA; Hancock’s Half Hour; Sykes; star persona; post-war British cinema; British popular culture; transgression; carnivalesque; comedy; femininity; nursing; class; spinster. 1 Hattie Jacques (1922 – 1980) was a gifted comedienne and actor who is now largely remembered for her roles as an overweight, strict and often lovelorn ‘battle-axe’ in the British Carry On series of low- budget comedy films between 1958 and 1973. A key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, Hattie Jacques’s star meanings are condensed around the contradictions she articulated between power, desire, femininity and class. -

The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan Hughes, University of Central Lancashire The North of England is a place-myth as much as a material reality. Conceptually it exists as the location where the economic, political, sociological, as well as climatological and geomorphological, phenomena particular to the region are reified into a set of socio-cultural qualities that serve to define it as different to conceptualisations of England and ‘Englishness’. Whilst the abstract nature of such a construction means that the geographical boundaries of the North are implicitly ill-defined, for ease of reference, and to maintain objectivity in defining individual texts as Northern films, this paper will adhere to the notion of a ‘seven county North’ (i.e. the pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire) that is increasingly being used as the geographical template for the North of England within social and cultural history.1 The British film industry in 1941 As 1940 drew to a close in Britain any memories of the phoney war of the spring of that year were likely to seem but distant recollections of a bygone age long dispersed by the brutal realities of the conflict. Outside of the immediate theatres of conflict the domestic industries that had catered for the demands of an increasingly affluent and consuming population were orientated towards the needs of a war economy as plant, machinery, and labour shifted into war production. -

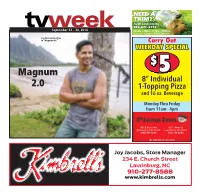

Magnum P.I.” Carry out Weekdaymanager’S Spespecialcial $ 2 Medium 2-Topping Magnum Pizzas5 2.0 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5And 16Each Oz

NEED A TRIM? AJW Landscaping 910-271-3777 September 22 - 28, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching Licensed – Insured – FREE Estimates 00941084 Jay Hernandez stars in “Magnum P.I.” Carry Out WEEKDAYMANAGEr’s SPESPECIALCIAL $ 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Magnum Pizzas5 2.0 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5and 16EACH oz. Beverage (AdditionalMonday toppings $1.40Thru each) Friday from 11am - 4pm 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, September 22, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Back to the well: ‘Magnum P.I.’ returns to television with CBS reboot By Kenneth Andeel er One,” 2018) in the role of Higgins, dependence on sexual tension in TV Media the straight woman to Magnum’s the new formula. That will ultimate- wild card, and fellow Americans ly come down to the skill and re- ame the most famous mustache Zachary Knighton (“Happy End- straint of the writing staff, however, Nto ever grace a TV screen. You ings”) and Stephen Hill (“Board- and there’s no inherent reason the have 10 seconds to deduce the an- walk Empire”) as Rick and TC, close new dynamic can’t be as engrossing swer, and should you fail, a shadowy friends of Magnum’s from his mili- as its prototype was. cabal of drug-dealing, bank-rob- tary past. There will be other notable cam- bing, helicopter-hijacking racketeers The pilot for the new series was eos, though. -

Audiovisual Translation: a Multimodal Corpus-Based Analy- Sis.” Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 21:4

Ayşe Şirin Okyayuz, Bilkent University Power, society and AVT in Turkey: an overview Abstract: The article relates the findings of an ongoing research project that encompasses several decades of AVT in Turkey. Drawing a matrix of relations and interactions between types of AVT (i.e. subtitling, dubbing, remakes, adaptations) and practices (i.e. censoring, choice of AV products) and the political as well as social realities and aspirations of certain periods, the aim is to provide a historical trajectory of AVT to exemplify the specific use of certain types of AVT in line with societal and political aspirations and developments. Lim- ited by the length of an article and the inability to provide AV material in printed format, the article provides an overview of the major eras of AVT and the political and societal shifts that necessitated or brought about changes to the AVT scene in the decades studied. 1. Introduction The discussion of issues such as the use of different types of AVT for specific purposes (i.e. localized adaptations of foreign AV products for building a national identity, dubbing with the standard dialect to support language standardization and learning, providing information flow and familiarity with foreign cultures through subtitling), social and political policies that influence AVT (i.e. tax re- ductions in films imports, foreign/domestic productions, audience viewing rates, censorship organs), power play (i.e. state led AV sector, elitist, ideological, and populist AV productions and translations), actors (i.e. governments, foreign firms and agreements) and technologies (i.e. dubbing, subtitling) are all of interest to the AVT researcher.