This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cassini Update

Cassini Update Dr. Linda Spilker Cassini Project Scientist Outer Planets Assessment Group 22 February 2017 Sols%ce Mission Inclina%on Profile equator Saturn wrt Inclination 22 February 2017 LJS-3 Year 3 Key Flybys Since Aug. 2016 OPAG T124 – Titan flyby (1584 km) • November 13, 2016 • LAST Radio Science flyby • One of only two (cf. T106) ideal bistatic observations capturing Titan’s Northern Seas • First and only bistatic observation of Punga Mare • Western Kraken Mare not explored by RSS before T125 – Titan flyby (3158 km) • November 29, 2016 • LAST Optical Remote Sensing targeted flyby • VIMS high-resolution map of the North Pole looking for variations at and around the seas and lakes. • CIRS last opportunity for vertical profile determination of gases (e.g. water, aerosols) • UVIS limb viewing opportunity at the highest spatial resolution available outside of occultations 22 February 2017 4 Interior of Hexagon Turning “Less Blue” • Bluish to golden haze results from increased production of photochemical hazes as north pole approaches summer solstice. • Hexagon acts as a barrier that prevents haze particles outside hexagon from migrating inward. • 5 Refracting Atmosphere Saturn's• 22unlit February rings appear 2017 to bend as they pass behind the planet’s darkened limb due• 6 to refraction by Saturn's upper atmosphere. (Resolution 5 km/pixel) Dione Harbors A Subsurface Ocean Researchers at the Royal Observatory of Belgium reanalyzed Cassini RSS gravity data• 7 of Dione and predict a crust 100 km thick with a global ocean 10’s of km deep. Titan’s Summer Clouds Pose a Mystery Why would clouds on Titan be visible in VIMS images, but not in ISS images? ISS ISS VIMS High, thin cirrus clouds that are optically thicker than Titan’s atmospheric haze at longer VIMS wavelengths,• 22 February but optically 2017 thinner than the haze at shorter ISS wavelengths, could be• 8 detected by VIMS while simultaneously lost in the haze to ISS. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

Privacy Policy

Privacy Policy Culmia Privacy Policy Culmia Desarrollos Inmobiliarios, S.L.U. (hereinafter, “the manager”), with headquarters in Madrid, Calle Génova, 27, Company Tax No. B-67186999, is an integral manager of property assets and a member of a Property Group to which it provides its services. The manager provides its services to the following property developers who are members of its Group: Company Company Company Company Tax Tax No. No. Saturn Holdco S.A.U. A88554100 Antea Activos Inmobiliarios B88554324 S.L.U. Thrym Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554142 Redes Promotora 1 Ma, B88093117 S.L.U. Erriap Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554159 Redes Promotora 2 Ma, B88093174 S.L.U. Daphne Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554167 Redes Promotora 3 Ma, B88093265 S.L.U. Dione Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554183 Redes Promotora 4 Ma, B88093356 S.L.U. Fornjot Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554191 Redes Promotora 5 Ma, B88093471 S.L.U. Greip Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554217 Redes Promotora 6 Ma, B88145073 S.L.U. Hiperion Activos Inmobiliarios B88554233 Redes Promotora 7 Ma, B88145123 S.L.U. S.L.U. Loge Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554241 Redes Promotora 8 Ma, B88145263 S.L.U. Kiviuq Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554258 Redes Promotora 9, S.L.U. B88159728 Narvi Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554266 Redes 2 2018 Iberica 2 B88160221 S.L.U. Polux Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554282 Redes 2 2018 Iberica 3 B88160239 S.L.U. Siarnaq Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554290 Redes 2 Promotora B88160247 Inversiones 2018 IV S.L.U. -

The Subsurface Habitability of Small, Icy Exomoons J

A&A 636, A50 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937035 & © ESO 2020 Astrophysics The subsurface habitability of small, icy exomoons J. N. K. Y. Tjoa1,?, M. Mueller1,2,3, and F. F. S. van der Tak1,2 1 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, Landleven 12, 9747 AD Groningen, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Landleven 12, 9747 AD Groningen, The Netherlands 3 Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Niels Bohrweg 2, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Received 1 November 2019 / Accepted 8 March 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Assuming our Solar System as typical, exomoons may outnumber exoplanets. If their habitability fraction is similar, they would thus constitute the largest portion of habitable real estate in the Universe. Icy moons in our Solar System, such as Europa and Enceladus, have already been shown to possess liquid water, a prerequisite for life on Earth. Aims. We intend to investigate under what thermal and orbital circumstances small, icy moons may sustain subsurface oceans and thus be “subsurface habitable”. We pay specific attention to tidal heating, which may keep a moon liquid far beyond the conservative habitable zone. Methods. We made use of a phenomenological approach to tidal heating. We computed the orbit averaged flux from both stellar and planetary (both thermal and reflected stellar) illumination. We then calculated subsurface temperatures depending on illumination and thermal conduction to the surface through the ice shell and an insulating layer of regolith. We adopted a conduction only model, ignoring volcanism and ice shell convection as an outlet for internal heat. -

The Gravity Field and Interior Structure of Dione

The gravity field and interior structure of Dione Marco Zannoni1*, Douglas Hemingway2,3, Luis Gomez Casajus1, Paolo Tortora1 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria Industriale, Università di Bologna, Forlì, Italy 2Department of Earth & Planetary Science, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, USA 3Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution for Science, Washington, DC, USA *Corresponding author. Abstract During its mission in the Saturn system, Cassini performed five close flybys of Dione. During three of them, radio tracking data were collected during the closest approach, allowing estimation of the full degree-2 gravity field by precise spacecraft orbit determination. 6 The gravity field of Dione is dominated by J2 and C22, for which our best estimates are J2 x 10 = 1496 ± 11 and 6 C22 x 10 = 364.8 ± 1.8 (unnormalized coefficients, 1-σ uncertainty). Their ratio is J2/C22 = 4.102 ± 0.044, showing a significative departure (about 17-σ) from the theoretical value of 10/3, predicted for a relaxed body in slow, synchronous rotation around a planet. Therefore, it is not possible to retrieve the moment of inertia directly from the measured gravitational field. The interior structure of Dione is investigated by a combined analysis of its gravity and topography, which exhibits an even larger deviation from hydrostatic equilibrium, suggesting some degree of compensation. The gravity of Dione is far from the expectation for an undifferentiated hydrostatic body, so we built a series of three-layer models, and considered both Airy and Pratt compensation mechanisms. The interpretation is non-unique, but Dione’s excess topography may suggest some degree of Airy-type isostasy, meaning that the outer ice shell is underlain by a higher density, lower viscosity layer, such as a subsurface liquid water ocean. -

Abstracts of the 50Th DDA Meeting (Boulder, CO)

Abstracts of the 50th DDA Meeting (Boulder, CO) American Astronomical Society June, 2019 100 — Dynamics on Asteroids break-up event around a Lagrange point. 100.01 — Simulations of a Synthetic Eurybates 100.02 — High-Fidelity Testing of Binary Asteroid Collisional Family Formation with Applications to 1999 KW4 Timothy Holt1; David Nesvorny2; Jonathan Horner1; Alex B. Davis1; Daniel Scheeres1 Rachel King1; Brad Carter1; Leigh Brookshaw1 1 Aerospace Engineering Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder 1 Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland (Boulder, Colorado, United States) (Longmont, Colorado, United States) 2 Southwest Research Institute (Boulder, Connecticut, United The commonly accepted formation process for asym- States) metric binary asteroids is the spin up and eventual fission of rubble pile asteroids as proposed by Walsh, Of the six recognized collisional families in the Jo- Richardson and Michel (Walsh et al., Nature 2008) vian Trojan swarms, the Eurybates family is the and Scheeres (Scheeres, Icarus 2007). In this theory largest, with over 200 recognized members. Located a rubble pile asteroid is spun up by YORP until it around the Jovian L4 Lagrange point, librations of reaches a critical spin rate and experiences a mass the members make this family an interesting study shedding event forming a close, low-eccentricity in orbital dynamics. The Jovian Trojans are thought satellite. Further work by Jacobson and Scheeres to have been captured during an early period of in- used a planar, two-ellipsoid model to analyze the stability in the Solar system. The parent body of the evolutionary pathways of such a formation event family, 3548 Eurybates is one of the targets for the from the moment the bodies initially fission (Jacob- LUCY spacecraft, and our work will provide a dy- son and Scheeres, Icarus 2011). -

Reddy Saturn's Small Wonders Astronomy 46 No 03 (2018)-1.Pdf

Saturn’s small wonders Usually known for its rings, the Saturn system is also home to some of our solar system’s most intriguing moons. by Francis Reddy Above: NASA’s Cassini mission took images as the spacecraft approached ye candy is not in short supply at Saturn. and Calypso orbit along with Tethys — an (left) and departed (right) For visitors who tire of watching the plan- arrangement thus far unseen among any other Saturn’s moon Phoebe et’s stormy atmosphere or gazing into the moons in the solar system. during its only close flyby of the satellite. Cassini solar system’s most beautiful and complex And this is just for starters. “The Saturn sys- passed just 1,285 miles ring system, there's always the giant satel- tem is full of surprises,” says Paul Schenk, a plan- (2,068 km) above the lite Titan to explore. This colossal moon etary geologist at the Lunar and Planetary surface on June 11, 2004. is bigger than Mercury and sports a hazy Institute in Houston. There’s a satellite that likely Phoebe is thought to be a centaur that might have orange atmosphere denser than Earth’s, originated in the Kuiper Belt, the storehouse of become a Jupiter-family producing methane rains that flow across icy bodies beyond Neptune’s orbit; a piebald comet, had Saturn not Titan’s icy landscape and pool into vast lakes. moon nearly encircled by an equatorial ridge captured it. NASA/JPL-CALTECH But look again. Even Saturn’s small moons containing some of the tallest mountains in the display some unusual dynamic relationships. -

Observing the Universe

ObservingObserving thethe UniverseUniverse :: aa TravelTravel ThroughThrough SpaceSpace andand TimeTime Enrico Flamini Agenzia Spaziale Italiana Tokyo 2009 When you rise your head to the night sky, what your eyes are observing may be astonishing. However it is only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum of the Universe: the visible . But any electromagnetic signal, indipendently from its frequency, travels at the speed of light. When we observe a star or a galaxy we see the photons produced at the moment of their production, their travel could have been incredibly long: it may be lasted millions or billions of years. Looking at the sky at frequencies much higher then visible, like in the X-ray or gamma-ray energy range, we can observe the so called “violent sky” where extremely energetic fenoena occurs.like Pulsar, quasars, AGN, Supernova CosmicCosmic RaysRays:: messengersmessengers fromfrom thethe extremeextreme universeuniverse We cannot see the deep universe at E > few TeV, since photons are attenuated through →e± on the CMB + IR backgrounds. But using cosmic rays we should be able to ‘see’ up to ~ 6 x 1010 GeV before they get attenuated by other interaction. Sources Sources → Primordial origin Primordial 7 Redshift z = 0 (t = 13.7 Gyr = now ! ) Going to a frequency lower then the visible light, and cooling down the instrument nearby absolute zero, it’s possible to observe signals produced millions or billions of years ago: we may travel near the instant of the formation of our universe: 13.7 By. Redshift z = 1.4 (t = 4.7 Gyr) Credits A. Cimatti Univ. Bologna Redshift z = 5.7 (t = 1 Gyr) Credits A. -

NWC SAF Convective Precipitation Product from MSG: a New Day-Time Method Based on Cloud Top Physical Properties

Tethys 2015, 12, 3–11 www.tethys.cat ISSN-1697-1523 eISSN-1139-3394 DOI:10.3369/tethys.2015.12.01 Journal edited by ACAM NWC SAF convective precipitation product from MSG: A new day-time method based on cloud top physical properties C. Marcos1, J. M. Sancho2 and F. J. Tapiador3 1Spanish Meteorological Agency (AEMET); Leonardo Prieto Castro, 8, 28071, Madrid 2Spanish Meteorological Agency (AEMET), Territorial delegation in Andalusia, Ceuta and Melilla; Demstenes, 4, 29010 Malaga 3Instituto de Ciencias Ambientales, University of Castilla-La Mancha; Avda. Carlos III s/n, 45071, Toledo Received: 3-XII-2014 – Accepted: 25-III-2015 – Original version Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract Several precipitation products use radiances and reflectances obtained from the Spinning En- hanced Visible and Infrared Imager (SEVIRI) to estimate convective precipitation. The direct use of these physical quantities in precipitation algorithms is known to generate an overestimation of the precipitation area and an underestimation of the rainfall rates. In order to extenuate these issues, the most recent Satellite Application Facility on Support to Nowcasting & Very Short Range Forecasting (NWC SAF/MSG) software package (version 2013) includes a new day-time algorithm that takes advantage of advances in cloud microphysics estimation, namely a better knowledge of Effective Radius (Reff ), Cloud Optical Thickness (COT) and Water Phase. The improved algorithm, known as Convective Rainfall Rate from Cloud Physical Properties (CRPh), uses such Cloud Top Physical Properties (CPP) to estimate rainfall rates from convective clouds on a SEVIRI pixel basis (about 3 km at nadir). This paper presents the novelties of the new algorithm and provides both a comparison of the product with the previous versions in the NWC SAF/MSG software package, and a validation with independent ground radar data from the Spanish Radar Network operated by AEMET. -

Cassini Finds Hints of Activity at Saturn Moon Dione 30 May 2013

Cassini finds hints of activity at Saturn moon Dione 30 May 2013 our solar system. They have been intriguing targets for geologists and scientists looking for the building blocks of life elsewhere in the solar system. The presence of a subsurface ocean at Dione would boost the astrobiological potential of this once- boring iceball. Hints of Dione's activity have recently come from Cassini, which has been exploring the Saturn system since 2004. The spacecraft's magnetometer has detected a faint particle stream coming from the moon, and images showed evidence for a possible liquid or slushy layer under its rock-hard The Cassini spacecraft looks down, almost directly at the ice crust. Other Cassini images have also revealed north pole of Dione. The feature just left of the terminator ancient, inactive fractures at Dione similar to those at bottom is Janiculum Dorsa, a long, roughly north- seen at Enceladus that currently spray water ice south trending ridge. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Space and organic particles. Science Institute The mountain examined in the latest paper—published in March in the journal Icarus—is called Janiculum Dorsa and ranges in height from (Phys.org) —From a distance, most of the Saturnian about 0.6 to 1.2 miles (1 to 2 kilometers). The moon Dione resembles a bland cueball. Thanks to moon's crust appears to pucker under this close-up images of a 500-mile-long (800-kilometer- mountain as much as about 0.3 mile (0.5 long) mountain on the moon from NASA's Cassini kilometer). spacecraft, scientists have found more evidence for the idea that Dione was likely active in the past. -

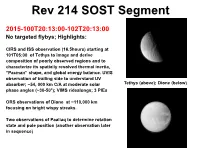

Rev 214 SOST Segment Titan Rainclouds 2015-100T20:13:00-102T20:13:00 Rhea No Targeted Flybys; Highlights

Rev 214 SOST Segment Titan rainclouds 2015-100T20:13:00-102T20:13:00 Rhea No targeted flybys; Highlights: CIRS and ISS observation (16.5hours) starting at 101T05:00 of Tethys to image and derive composition of poorly observed regions and to characterize its spatially resolved thermal inertia, “Pacman” shape, and global energy balance. UVIS observation of trailing side to understand UV absorber; ~54, 000 km C/A at moderate solar Tethys (above); Dione (below) phase angles (~30-50°); VIMS ridealongs; 3 PIEs ORS observations of Dione at ~110,000 km focusing on bright wispy streaks. CIRS PDT Design Two observations of Paaliaq to determine rotation state and pole position (another observation later in sequence) Helene The Tethys observations will focus on the above area. Iapetus observing campaign (No PIES) Rhea On rev 213-214 (XD Segment) there are five distant (~1 million km) ORS Iapetus observations designed to cover regions that are poorly imaged. The solar phase angle is ~40 degrees throughout the observing period, which is ideal for mapping geologic features. Composition and thermal properties will also be studied. Tethys The observations extend from 2015- 085T21:52-091T20:17 and cover the N. trailing (bright) hemisphere. ISS is CIRS PDT Design prime except for one observation, which is CIRS prime. Iapetus is about 240 ISS pixels at 6 VIMS (hi-res) pixels. Iapetus Helene This part of the campaign will focus on the above area. Plume Observation in S88 (not a PIE) XD_214_215 Rhea ISS_214EN_PLMHPMR001_PRIME 2015-103T23:10-104T09:00 VIMS and UVIS in ridealong; pointing requirements (must point within 15 ° of Saturn center ; added to spreadsheet) Science Goals:recap To obtain different viewing geometries which better characterize plume morphology, Tethys particle size, and the relationship between plumes and surface features and thermal anomalies. -

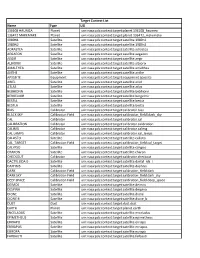

PDS4 Context List

Target Context List Name Type LID 136108 HAUMEA Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136108_haumea 136472 MAKEMAKE Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136472_makemake 1989N1 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n1 1989N2 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n2 ADRASTEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.adrastea AEGAEON Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegaeon AEGIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegir ALBIORIX Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.albiorix AMALTHEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.amalthea ANTHE Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.anthe APXSSITE Equipment urn:nasa:pds:context:target:equipment.apxssite ARIEL Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.ariel ATLAS Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.atlas BEBHIONN Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bebhionn BERGELMIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bergelmir BESTIA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestia BESTLA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestla BIAS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.bias BLACK SKY Calibration Field urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibration_field.black_sky CAL Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal CALIBRATION Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calibration CALIMG Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calimg CAL LAMPS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal_lamps CALLISTO Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.callisto