The Gravity Field and Interior Structure of Dione

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:1912.09192V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 24 Feb 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2925/arxiv-1912-09192v2-astro-ph-ep-24-feb-2020-2925.webp)

Arxiv:1912.09192V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 24 Feb 2020

Draft version February 25, 2020 Typeset using LATEX preprint style in AASTeX62 Photometric analyses of Saturn's small moons: Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene are dark; Helene and Calypso are bright. M. M. Hedman,1 P. Helfenstein,2 R. O. Chancia,1, 3 P. Thomas,2 E. Roussos,4 C. Paranicas,5 and A. J. Verbiscer6 1Department of Physics, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844 2Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, Cornell University, Ithaca NY 14853 3Center for Imaging Science, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester NY 14623 4Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, G¨ottingen,Germany 37077 5APL, John Hopkins University, Laurel MD 20723 6Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904 ABSTRACT We examine the surface brightnesses of Saturn's smaller satellites using a photometric model that explicitly accounts for their elongated shapes and thus facilitates compar- isons among different moons. Analyses of Cassini imaging data with this model reveals that the moons Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene are darker than one would expect given trends previously observed among the nearby mid-sized satellites. On the other hand, the trojan moons Calypso and Helene have substantially brighter surfaces than their co-orbital companions Tethys and Dione. These observations are inconsistent with the moons' surface brightnesses being entirely controlled by the local flux of E-ring par- ticles, and therefore strongly imply that other phenomena are affecting their surface properties. The darkness of Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene is correlated with the fluxes of high-energy protons, implying that high-energy radiation is responsible for darkening these small moons. Meanwhile, Prometheus and Pandora appear to be brightened by their interactions with nearby dusty F ring, implying that enhanced dust fluxes are most likely responsible for Calypso's and Helene's excess brightness. -

Cassini Update

Cassini Update Dr. Linda Spilker Cassini Project Scientist Outer Planets Assessment Group 22 February 2017 Sols%ce Mission Inclina%on Profile equator Saturn wrt Inclination 22 February 2017 LJS-3 Year 3 Key Flybys Since Aug. 2016 OPAG T124 – Titan flyby (1584 km) • November 13, 2016 • LAST Radio Science flyby • One of only two (cf. T106) ideal bistatic observations capturing Titan’s Northern Seas • First and only bistatic observation of Punga Mare • Western Kraken Mare not explored by RSS before T125 – Titan flyby (3158 km) • November 29, 2016 • LAST Optical Remote Sensing targeted flyby • VIMS high-resolution map of the North Pole looking for variations at and around the seas and lakes. • CIRS last opportunity for vertical profile determination of gases (e.g. water, aerosols) • UVIS limb viewing opportunity at the highest spatial resolution available outside of occultations 22 February 2017 4 Interior of Hexagon Turning “Less Blue” • Bluish to golden haze results from increased production of photochemical hazes as north pole approaches summer solstice. • Hexagon acts as a barrier that prevents haze particles outside hexagon from migrating inward. • 5 Refracting Atmosphere Saturn's• 22unlit February rings appear 2017 to bend as they pass behind the planet’s darkened limb due• 6 to refraction by Saturn's upper atmosphere. (Resolution 5 km/pixel) Dione Harbors A Subsurface Ocean Researchers at the Royal Observatory of Belgium reanalyzed Cassini RSS gravity data• 7 of Dione and predict a crust 100 km thick with a global ocean 10’s of km deep. Titan’s Summer Clouds Pose a Mystery Why would clouds on Titan be visible in VIMS images, but not in ISS images? ISS ISS VIMS High, thin cirrus clouds that are optically thicker than Titan’s atmospheric haze at longer VIMS wavelengths,• 22 February but optically 2017 thinner than the haze at shorter ISS wavelengths, could be• 8 detected by VIMS while simultaneously lost in the haze to ISS. -

The Orbits of Saturn's Small Satellites Derived From

The Astronomical Journal, 132:692–710, 2006 August A # 2006. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE ORBITS OF SATURN’S SMALL SATELLITES DERIVED FROM COMBINED HISTORIC AND CASSINI IMAGING OBSERVATIONS J. N. Spitale CICLOPS, Space Science Institute, 4750 Walnut Street, Suite 205, Boulder, CO 80301; [email protected] R. A. Jacobson Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099 C. C. Porco CICLOPS, Space Science Institute, 4750 Walnut Street, Suite 205, Boulder, CO 80301 and W. M. Owen, Jr. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099 Received 2006 February 28; accepted 2006 April 12 ABSTRACT We report on the orbits of the small, inner Saturnian satellites, either recovered or newly discovered in recent Cassini imaging observations. The orbits presented here reflect improvements over our previously published values in that the time base of Cassini observations has been extended, and numerical orbital integrations have been performed in those cases in which simple precessing elliptical, inclined orbit solutions were found to be inadequate. Using combined Cassini and Voyager observations, we obtain an eccentricity for Pan 7 times smaller than previously reported because of the predominance of higher quality Cassini data in the fit. The orbit of the small satellite (S/2005 S1 [Daphnis]) discovered by Cassini in the Keeler gap in the outer A ring appears to be circular and coplanar; no external perturbations are appar- ent. Refined orbits of Atlas, Prometheus, Pandora, Janus, and Epimetheus are based on Cassini , Voyager, Hubble Space Telescope, and Earth-based data and a numerical integration perturbed by all the massive satellites and each other. -

Privacy Policy

Privacy Policy Culmia Privacy Policy Culmia Desarrollos Inmobiliarios, S.L.U. (hereinafter, “the manager”), with headquarters in Madrid, Calle Génova, 27, Company Tax No. B-67186999, is an integral manager of property assets and a member of a Property Group to which it provides its services. The manager provides its services to the following property developers who are members of its Group: Company Company Company Company Tax Tax No. No. Saturn Holdco S.A.U. A88554100 Antea Activos Inmobiliarios B88554324 S.L.U. Thrym Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554142 Redes Promotora 1 Ma, B88093117 S.L.U. Erriap Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554159 Redes Promotora 2 Ma, B88093174 S.L.U. Daphne Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554167 Redes Promotora 3 Ma, B88093265 S.L.U. Dione Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554183 Redes Promotora 4 Ma, B88093356 S.L.U. Fornjot Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554191 Redes Promotora 5 Ma, B88093471 S.L.U. Greip Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554217 Redes Promotora 6 Ma, B88145073 S.L.U. Hiperion Activos Inmobiliarios B88554233 Redes Promotora 7 Ma, B88145123 S.L.U. S.L.U. Loge Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554241 Redes Promotora 8 Ma, B88145263 S.L.U. Kiviuq Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554258 Redes Promotora 9, S.L.U. B88159728 Narvi Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554266 Redes 2 2018 Iberica 2 B88160221 S.L.U. Polux Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554282 Redes 2 2018 Iberica 3 B88160239 S.L.U. Siarnaq Activos Inmobiliarios S.L.U. B88554290 Redes 2 Promotora B88160247 Inversiones 2018 IV S.L.U. -

The Subsurface Habitability of Small, Icy Exomoons J

A&A 636, A50 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937035 & © ESO 2020 Astrophysics The subsurface habitability of small, icy exomoons J. N. K. Y. Tjoa1,?, M. Mueller1,2,3, and F. F. S. van der Tak1,2 1 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, Landleven 12, 9747 AD Groningen, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Landleven 12, 9747 AD Groningen, The Netherlands 3 Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Niels Bohrweg 2, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Received 1 November 2019 / Accepted 8 March 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Assuming our Solar System as typical, exomoons may outnumber exoplanets. If their habitability fraction is similar, they would thus constitute the largest portion of habitable real estate in the Universe. Icy moons in our Solar System, such as Europa and Enceladus, have already been shown to possess liquid water, a prerequisite for life on Earth. Aims. We intend to investigate under what thermal and orbital circumstances small, icy moons may sustain subsurface oceans and thus be “subsurface habitable”. We pay specific attention to tidal heating, which may keep a moon liquid far beyond the conservative habitable zone. Methods. We made use of a phenomenological approach to tidal heating. We computed the orbit averaged flux from both stellar and planetary (both thermal and reflected stellar) illumination. We then calculated subsurface temperatures depending on illumination and thermal conduction to the surface through the ice shell and an insulating layer of regolith. We adopted a conduction only model, ignoring volcanism and ice shell convection as an outlet for internal heat. -

Abstracts of the 50Th DDA Meeting (Boulder, CO)

Abstracts of the 50th DDA Meeting (Boulder, CO) American Astronomical Society June, 2019 100 — Dynamics on Asteroids break-up event around a Lagrange point. 100.01 — Simulations of a Synthetic Eurybates 100.02 — High-Fidelity Testing of Binary Asteroid Collisional Family Formation with Applications to 1999 KW4 Timothy Holt1; David Nesvorny2; Jonathan Horner1; Alex B. Davis1; Daniel Scheeres1 Rachel King1; Brad Carter1; Leigh Brookshaw1 1 Aerospace Engineering Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder 1 Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland (Boulder, Colorado, United States) (Longmont, Colorado, United States) 2 Southwest Research Institute (Boulder, Connecticut, United The commonly accepted formation process for asym- States) metric binary asteroids is the spin up and eventual fission of rubble pile asteroids as proposed by Walsh, Of the six recognized collisional families in the Jo- Richardson and Michel (Walsh et al., Nature 2008) vian Trojan swarms, the Eurybates family is the and Scheeres (Scheeres, Icarus 2007). In this theory largest, with over 200 recognized members. Located a rubble pile asteroid is spun up by YORP until it around the Jovian L4 Lagrange point, librations of reaches a critical spin rate and experiences a mass the members make this family an interesting study shedding event forming a close, low-eccentricity in orbital dynamics. The Jovian Trojans are thought satellite. Further work by Jacobson and Scheeres to have been captured during an early period of in- used a planar, two-ellipsoid model to analyze the stability in the Solar system. The parent body of the evolutionary pathways of such a formation event family, 3548 Eurybates is one of the targets for the from the moment the bodies initially fission (Jacob- LUCY spacecraft, and our work will provide a dy- son and Scheeres, Icarus 2011). -

The Sources and Dynamical Mechanisms Responsible for Differing Regolith Cover on Satellites Embedded in Saturn’S E Ring

50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2019 (LPI Contrib. No. 2132) 2790.pdf WHY SO MUTED? THE SOURCES AND DYNAMICAL MECHANISMS RESPONSIBLE FOR DIFFERING REGOLITH COVER ON SATELLITES EMBEDDED IN SATURN’S E RING. S. J. Morrison1 and S. G. Zaidi1, 1Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds, 525 Davey Laboratory, The Pennsylvania State Uni- versity, University Park, PA, 16802, USA ([email protected]) Introduction: Saturn’s E ring, sourced primarily by resonances with Tethys and Dione. We also numerically cryovolcanic material erupted from Enceladus, extends integrate E ring particle trajectories including these outward from Enceladus’ orbit to beyond Dione’s orbit forces using the integrator package REBOUND and RE- [1][2]. Amongst the satellites embedded in this ring, BOUNDx [10-12]. We use initial orbits for the Satur- there are observed differences in regolith cover. In par- nian System from [13] and estimated masses for the tad- ticular, the small satellites Telesto, Calypso, Helene, pole moons from [7] that assume an average density of and Polydeuces have more muted surfaces, an absence 0.6 g/cc. We include Saturn’s gravitational harmonics of small craters, and downslope transport of regolith up to J4 and plasma drag forces arising from collisions within large craters than observed on Tethys and Dione with co-rotating O+ ions, the primary constituent of on similar distance scales [3][4]. However, these small plasma in the region of the Saturnian system of interest. satellites orbit in a different dynamical environment: Results: To provide insight into whether outwardly Telesto and Calypso are on leading and trailing tadpole drifting E ring particles should accumulate in the 1:1 orbits about the L4 and L5 Lagrange points in the co- resonances with Tethys and Dione, we compare the orbital 1:1 mean motion resonance with Tethys, respec- timescale for a particle of a given size to drift across the tively, as are Helene and Polydeuces tadpoles of Dione maximum libration width of this resonance to the corre- [e.g. -

Observing the Universe

ObservingObserving thethe UniverseUniverse :: aa TravelTravel ThroughThrough SpaceSpace andand TimeTime Enrico Flamini Agenzia Spaziale Italiana Tokyo 2009 When you rise your head to the night sky, what your eyes are observing may be astonishing. However it is only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum of the Universe: the visible . But any electromagnetic signal, indipendently from its frequency, travels at the speed of light. When we observe a star or a galaxy we see the photons produced at the moment of their production, their travel could have been incredibly long: it may be lasted millions or billions of years. Looking at the sky at frequencies much higher then visible, like in the X-ray or gamma-ray energy range, we can observe the so called “violent sky” where extremely energetic fenoena occurs.like Pulsar, quasars, AGN, Supernova CosmicCosmic RaysRays:: messengersmessengers fromfrom thethe extremeextreme universeuniverse We cannot see the deep universe at E > few TeV, since photons are attenuated through →e± on the CMB + IR backgrounds. But using cosmic rays we should be able to ‘see’ up to ~ 6 x 1010 GeV before they get attenuated by other interaction. Sources Sources → Primordial origin Primordial 7 Redshift z = 0 (t = 13.7 Gyr = now ! ) Going to a frequency lower then the visible light, and cooling down the instrument nearby absolute zero, it’s possible to observe signals produced millions or billions of years ago: we may travel near the instant of the formation of our universe: 13.7 By. Redshift z = 1.4 (t = 4.7 Gyr) Credits A. Cimatti Univ. Bologna Redshift z = 5.7 (t = 1 Gyr) Credits A. -

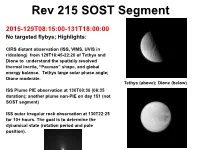

Rev 215 SOST Segment Titan Rainclouds 2015-129T08:15:00-131T18:00:00 Rhea No Targeted Flybys; Highlights

Rev 215 SOST Segment Titan rainclouds 2015-129T08:15:00-131T18:00:00 Rhea No targeted flybys; Highlights: CIRS distant observation (ISS, VIMS, UVIS in ridealong) from 129T16:45-22:20 of Tethys and Dione to understand the spatially resolved thermal inertia, “Pacman” shape, and global energy balance. Tethys large solar phase angle; Dione moderate. Tethys (above); Dione (below) ISS Plume PIE observation at 130T00:30 (06:35 duration); another plume non-PIE on day 151 (not SOST segment) ISS outer irregular rock observation at 130T22:25 CIRS PDT Design for 10+ hours. The goal is to determine the dynamical state (rotation period and pole position). Helene Rev 215 SOST Segment, cont’d. Titan rainclouds Rhea Flyby of Polydeuces BEST EVER by a factor of 2 Polydeuces is a Dione Lagrangian that was discovered by Cassini. The goal of this observation is to study its morphology, size, albedo, and derive its composition to understand its origin and relationship to Dione and other moons. Observation starts at 129T22:20 (May 10, 2015), with a closest approach around 34,000 with a moderate solar phase angle. This is just the resolution where features (craters, CIRS PDT Design etc.) may start to appear on this irregular moon. Polydeuces, Cassini’s own satellite Helene Hyperion observing campaign (Not a PIE) Rhea On rev 216-217 (XD Segment) there is a ~34,000 ORS Hyperion Flyby designed to cover regions that may have poorly imaged (Hyperion is in chaotic rotation, so the location will be a surprise). The solar phase angle is moderate throughout the observing period, which is ideal for mapping geologic Features. -

Cassini Finds Hints of Activity at Saturn Moon Dione 30 May 2013

Cassini finds hints of activity at Saturn moon Dione 30 May 2013 our solar system. They have been intriguing targets for geologists and scientists looking for the building blocks of life elsewhere in the solar system. The presence of a subsurface ocean at Dione would boost the astrobiological potential of this once- boring iceball. Hints of Dione's activity have recently come from Cassini, which has been exploring the Saturn system since 2004. The spacecraft's magnetometer has detected a faint particle stream coming from the moon, and images showed evidence for a possible liquid or slushy layer under its rock-hard The Cassini spacecraft looks down, almost directly at the ice crust. Other Cassini images have also revealed north pole of Dione. The feature just left of the terminator ancient, inactive fractures at Dione similar to those at bottom is Janiculum Dorsa, a long, roughly north- seen at Enceladus that currently spray water ice south trending ridge. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Space and organic particles. Science Institute The mountain examined in the latest paper—published in March in the journal Icarus—is called Janiculum Dorsa and ranges in height from (Phys.org) —From a distance, most of the Saturnian about 0.6 to 1.2 miles (1 to 2 kilometers). The moon Dione resembles a bland cueball. Thanks to moon's crust appears to pucker under this close-up images of a 500-mile-long (800-kilometer- mountain as much as about 0.3 mile (0.5 long) mountain on the moon from NASA's Cassini kilometer). spacecraft, scientists have found more evidence for the idea that Dione was likely active in the past. -

Moons of Saturn

National Aeronautics and Space Administration 0 300,000,000 900,000,000 1,500,000,000 2,100,000,000 2,700,000,000 3,300,000,000 3,900,000,000 4,500,000,000 5,100,000,000 5,700,000,000 kilometers Moons of Saturn www.nasa.gov Saturn, the sixth planet from the Sun, is home to a vast array • Phoebe orbits the planet in a direction opposite that of Saturn’s • Fastest Orbit Pan of intriguing and unique satellites — 53 plus 9 awaiting official larger moons, as do several of the recently discovered moons. Pan’s Orbit Around Saturn 13.8 hours confirmation. Christiaan Huygens discovered the first known • Mimas has an enormous crater on one side, the result of an • Number of Moons Discovered by Voyager 3 moon of Saturn. The year was 1655 and the moon is Titan. impact that nearly split the moon apart. (Atlas, Prometheus, and Pandora) Jean-Dominique Cassini made the next four discoveries: Iapetus (1671), Rhea (1672), Dione (1684), and Tethys (1684). Mimas and • Enceladus displays evidence of active ice volcanism: Cassini • Number of Moons Discovered by Cassini 6 Enceladus were both discovered by William Herschel in 1789. observed warm fractures where evaporating ice evidently es- (Methone, Pallene, Polydeuces, Daphnis, Anthe, and Aegaeon) The next two discoveries came at intervals of 50 or more years capes and forms a huge cloud of water vapor over the south — Hyperion (1848) and Phoebe (1898). pole. ABOUT THE IMAGES As telescopic resolving power improved, Saturn’s family of • Hyperion has an odd flattened shape and rotates chaotically, 1 2 3 1 Cassini’s visual known moons grew. -

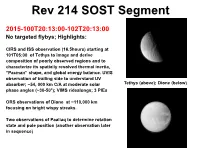

Rev 214 SOST Segment Titan Rainclouds 2015-100T20:13:00-102T20:13:00 Rhea No Targeted Flybys; Highlights

Rev 214 SOST Segment Titan rainclouds 2015-100T20:13:00-102T20:13:00 Rhea No targeted flybys; Highlights: CIRS and ISS observation (16.5hours) starting at 101T05:00 of Tethys to image and derive composition of poorly observed regions and to characterize its spatially resolved thermal inertia, “Pacman” shape, and global energy balance. UVIS observation of trailing side to understand UV absorber; ~54, 000 km C/A at moderate solar Tethys (above); Dione (below) phase angles (~30-50°); VIMS ridealongs; 3 PIEs ORS observations of Dione at ~110,000 km focusing on bright wispy streaks. CIRS PDT Design Two observations of Paaliaq to determine rotation state and pole position (another observation later in sequence) Helene The Tethys observations will focus on the above area. Iapetus observing campaign (No PIES) Rhea On rev 213-214 (XD Segment) there are five distant (~1 million km) ORS Iapetus observations designed to cover regions that are poorly imaged. The solar phase angle is ~40 degrees throughout the observing period, which is ideal for mapping geologic features. Composition and thermal properties will also be studied. Tethys The observations extend from 2015- 085T21:52-091T20:17 and cover the N. trailing (bright) hemisphere. ISS is CIRS PDT Design prime except for one observation, which is CIRS prime. Iapetus is about 240 ISS pixels at 6 VIMS (hi-res) pixels. Iapetus Helene This part of the campaign will focus on the above area. Plume Observation in S88 (not a PIE) XD_214_215 Rhea ISS_214EN_PLMHPMR001_PRIME 2015-103T23:10-104T09:00 VIMS and UVIS in ridealong; pointing requirements (must point within 15 ° of Saturn center ; added to spreadsheet) Science Goals:recap To obtain different viewing geometries which better characterize plume morphology, Tethys particle size, and the relationship between plumes and surface features and thermal anomalies.