Arxiv:Math/0701882V1 [Math.NT] 30 Jan 2007 Ojcue1.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Elliptic Modular Curves) JS Milne

Modular Functions and Modular Forms (Elliptic Modular Curves) J.S. Milne Version 1.30 April 26, 2012 This is an introduction to the arithmetic theory of modular functions and modular forms, with a greater emphasis on the geometry than most accounts. BibTeX information: @misc{milneMF, author={Milne, James S.}, title={Modular Functions and Modular Forms (v1.30)}, year={2012}, note={Available at www.jmilne.org/math/}, pages={138} } v1.10 May 22, 1997; first version on the web; 128 pages. v1.20 November 23, 2009; new style; minor fixes and improvements; added list of symbols; 129 pages. v1.30 April 26, 2010. Corrected; many minor revisions. 138 pages. Please send comments and corrections to me at the address on my website http://www.jmilne.org/math/. The photograph is of Lake Manapouri, Fiordland, New Zealand. Copyright c 1997, 2009, 2012 J.S. Milne. Single paper copies for noncommercial personal use may be made without explicit permission from the copyright holder. Contents Contents 3 Introduction ..................................... 5 I The Analytic Theory 13 1 Preliminaries ................................. 13 2 Elliptic Modular Curves as Riemann Surfaces . 25 3 Elliptic Functions ............................... 41 4 Modular Functions and Modular Forms ................... 48 5 Hecke Operators ............................... 68 II The Algebro-Geometric Theory 89 6 The Modular Equation for 0.N / ...................... 89 7 The Canonical Model of X0.N / over Q ................... 93 8 Modular Curves as Moduli Varieties ..................... 99 9 Modular Forms, Dirichlet Series, and Functional Equations . 104 10 Correspondences on Curves; the Theorem of Eichler-Shimura . 108 11 Curves and their Zeta Functions . 112 12 Complex Multiplication for Elliptic Curves Q . -

Elliptic Curves, Modularity, and Fermat's Last Theorem

Elliptic curves, modularity, and Fermat's Last Theorem For background and (most) proofs, we refer to [1]. 1 Weierstrass models Let K be any field. For any a1; a2; a3; a4; a6 2 K consider the plane projective curve C given by the equation 2 2 3 2 2 3 y z + a1xyz + a3yz = x + a2x z + a4xz + a6z : (1) An equation as above is called a Weierstrass equation. We also say that (1) is a Weierstrass model for C. L-Rational points For any field extension L=K we can consider the L-rational points on C, i.e. the points on C with coordinates in L: 2 C(L) := f(x : y : z) 2 PL : equation (1) is satisfied g: The point at infinity The point O := (0 : 1 : 0) 2 C(K) is the only K-rational point on C with z = 0. It is always smooth. Most of the time we shall instead of a homogeneous Weierstrass equation write an affine Weierstrass equation: 2 3 2 C : y + a1xy + a3y = x + a2x + a4x + a6 (2) which is understood to define a plane projective curve. The discriminant Define 2 b2 := a1 + 4a2; b4 := 2a4 + a1a3; 2 b6 := a3 + 4a6; 2 2 2 b8 := a1a6 + 4a2a6 − a1a3a4 + a2a3 − a4: For any Weierstrass equation we define its discriminant 2 3 2 ∆ := −b2b8 − 8b4 − 27b6 + 9b2b4b6: 1 Note that if char(K) 6= 2, then we can perform the coordinate transformation 2 3 2 y 7! (y − a1x − a3)=2 to arrive at an equation y = 4x + b2x + 2b4x + b6. -

The Klein Quartic in Number Theory

The Eightfold Way MSRI Publications Volume 35, 1998 The Klein Quartic in Number Theory NOAM D. ELKIES Abstract. We describe the Klein quartic X and highlight some of its re- markable properties that are of particular interest in number theory. These include extremal properties in characteristics 2, 3, and 7, the primes divid- ing the order of the automorphism group of X; an explicit identification of X with the modular curve X(7); and applications to the class number 1 problem and the case n = 7 of Fermat. Introduction Overview. In this expository paper we describe some of the remarkable prop- erties of the Klein quartic that are of particular interest in number theory. The Klein quartic X is the unique curve of genus 3 over C with an automorphism group G of size 168, the maximum for its genus. Since G is central to the story, we begin with a detailed description of G and its representation on the 2 three-dimensional space V in whose projectivization P(V )=P the Klein quar- tic lives. The first section is devoted to this representation and its invariants, starting over C and then considering arithmetical questions of fields of definition and integral structures. There we also encounter a G-lattice that later occurs as both the period lattice and a Mordell–Weil lattice for X. In the second section we introduce X and investigate it as a Riemann surface with automorphisms by G. In the third section we consider the arithmetic of X: rational points, relations with the Fermat curve and Fermat’s “Last Theorem” for exponent 7, and some extremal properties of the reduction of X modulo the primes 2, 3, 7 dividing #G. -

The Modularity Theorem

R. van Dobben de Bruyn The Modularity Theorem Bachelor's thesis, June 21, 2011 Supervisors: Dr R.M. van Luijk, Dr C. Salgado Mathematisch Instituut, Universiteit Leiden Contents Introduction4 1 Elliptic Curves6 1.1 Definitions and Examples......................6 1.2 Minimal Weierstrass Form...................... 11 1.3 Reduction Modulo Primes...................... 14 1.4 The Frey Curve and Fermat's Last Theorem............ 15 2 Modular Forms 18 2.1 Definitions............................... 18 2.2 Eisenstein Series and the Discriminant............... 21 2.3 The Ring of Modular Forms..................... 25 2.4 Congruence Subgroups........................ 28 3 The Modularity Theorem 36 3.1 Statement of the Theorem...................... 36 3.2 Fermat's Last Theorem....................... 36 References 39 2 Introduction One of the longest standing open problems in mathematics was Fermat's Last Theorem, asserting that the equation an + bn = cn does not have any nontrivial (i.e. with abc 6= 0) integral solutions when n is larger than 2. The proof, which was completed in 1995 by Wiles and Taylor, relied heavily on the Modularity Theorem, relating elliptic curves over Q to modular forms. The Modularity Theorem has many different forms, some of which are stated in an analytic way using Riemann surfaces, while others are stated in a more algebraic way, using for instance L-series or Galois representations. This text will present an elegant, elementary formulation of the theorem, using nothing more than some basic vocabulary of both elliptic curves and modular forms. For elliptic curves E over Q, we will examine the reduction E~ of E modulo any prime p, thus introducing the quantity ~ ap(E) = p + 1 − #E(Fp): We will also give an almost complete description of the conductor NE associated to an elliptic curve E, and compute it for the curve used in the proof of Fermat's Last Theorem. -

"Rank Zero Quadratic Twists of Modular Elliptic Curves" by Ken

RANK ZERO QUADRATIC TWISTS OF MODULAR ELLIPTIC CURVES Ken Ono Abstract. In [11] L. Mai and M. R. Murty proved that if E is a modular elliptic curve with conductor N, then there exists infinitely many square-free integers D ≡ 1 mod 4N such that ED, the D−quadratic twist of E, has rank 0. Moreover assuming the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture, they obtain analytic estimates on the lower bounds for the orders of their Tate-Shafarevich groups. However regarding ranks, simply by the sign of functional equations, it is not expected that there will be infinitely many square-free D in every arithmetic progression r (mod t) where gcd(r, t) is square-free such that ED has rank zero. Given a square-free positive integer r, under mild conditions we show that there ×2 exists an integer tr and a positive integer N where tr ≡ r mod Qp for all p | N, such that 0 there are infinitely many positive square-free integers D ≡ tr mod N where ED has rank 0 0 Q zero. The modulus N is defined by N := 8 p|N p where the product is over odd primes p dividing N. As an example of this theorem, let E be defined by y2 = x3 + 15x2 + 36x. If r = 1, 3, 5, 9, 11, 13, 17, 19, 21, then there exists infinitely many positive square-free in- tegers D ≡ r mod 24 such that ED has rank 0. As another example, let E be defined by y2 = x3 − 1. If r = 1, 2, 5, 10, 13, 14, 17, or 22, then there exists infinitely many positive square-free integers D ≡ r mod 24 such that ED has rank 0. -

Elliptic Modular Curves)

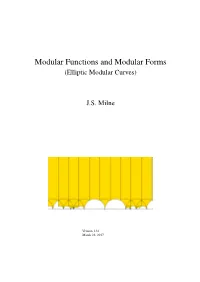

Modular Functions and Modular Forms (Elliptic Modular Curves) J.S. Milne Version 1.31 March 22, 2017 This is an introduction to the arithmetic theory of modular functions and modular forms, with a greater emphasis on the geometry than most accounts. BibTeX information: @misc{milneMF, author={Milne, James S.}, title={Modular Functions and Modular Forms (v1.31)}, year={2017}, note={Available at www.jmilne.org/math/}, pages={134} } v1.10 May 22, 1997; first version on the web; 128 pages. v1.20 November 23, 2009; new style; minor fixes and improvements; added list of symbols; 129 pages. v1.30 April 26, 2010. Corrected; many minor revisions. 138 pages. v1.31 March 22, 2017. Corrected; minor revisions. 133 pages. Please send comments and corrections to me at the address on my website http://www.jmilne.org/math/. The picture shows a fundamental domain for 1.10/, as drawn by the fundamental domain drawer of H. Verrill. Copyright c 1997, 2009, 2012, 2017 J.S. Milne. Single paper copies for noncommercial personal use may be made without explicit permission from the copyright holder. Contents Contents3 Introduction..................................... 5 I The Analytic Theory 13 1 Preliminaries ................................. 13 2 Elliptic Modular Curves as Riemann Surfaces................ 25 3 Elliptic Functions............................... 41 4 Modular Functions and Modular Forms ................... 48 5 Hecke Operators ............................... 67 II The Algebro-Geometric Theory 87 6 The Modular Equation for 0.N / ...................... 87 7 The Canonical Model of X0.N / over Q ................... 91 8 Modular Curves as Moduli Varieties..................... 97 9 Modular Forms, Dirichlet Series, and Functional Equations . 101 10 Correspondences on Curves; the Theorem of Eichler-Shimura . -

Arithmetical Problems in Number Fields, Abelian Varieties and Modular Forms*

CONTRIBUTIONS to SCIENCE, 1 (2): 125-145 (1999) Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona Arithmetical problems in number fields, abelian varieties and modular forms* P. Bayer** et al. Abstract Resum Number theory, a fascinating area in mathematics and one La teoria de nombres, una àrea de la matemàtica fascinant i of the oldest, has experienced spectacular progress in re- de les més antigues, ha experimentat un progrés especta- cent years. The development of a deep theoretical back- cular durant els darrers anys. El desenvolupament d’una ground and the implementation of algorithms have led to base teòrica profunda i la implementació d’algoritmes han new and interesting interrelations with mathematics in gen- conduït a noves interrelacions matemàtiques interessants eral which have paved the way for the emergence of major que han fet palesos teoremes importants en aquesta àrea. theorems in the area. Aquest informe resumeix les contribucions a la teoria de This report summarizes the contribution to number theory nombres dutes a terme per les persones del Seminari de made by the members of the Seminari de Teoria de Teoria de Nombres (UB-UAB-UPC) de Barcelona. Els seus Nombres (UB-UAB-UPC) in Barcelona. These results are resultats són citats en connexió amb l’estat actual d’alguns presented in connection with the state of certain arithmetical problemes aritmètics, de manera que aquesta monografia problems, and so this monograph seeks to provide readers cerca proporcionar al públic lector una ullada sobre algunes with a glimpse of some specific lines of current mathemati- línies específiques de la recerca matemàtica actual. cal research. -

MODULAR CURVES and MODULAR FORMS All of the Material Covered Here Can Be Found in the References, Though I Claim Responsibility

MODULAR CURVES AND MODULAR FORMS All of the material covered here can be found in the references, though I claim responsibility for mistakes. As these are very rough notes, I have not been diligent in adding citations for each specific results. The advanced reader should consult [1]. 1. Basic Theory of Elliptic Curves Elliptic curves admit numerous descriptions: projective curves of genus 1 with a distinguished point, varieties with equations y2 = x3 + ax + b, complete group varieties of dimension 1, etc. All are equivalent and it is instructive to see how one goes from one object to the next. Our goal is to classify elliptic curves up to isomorphism. Given a field K, we will denote by Ell(K) to be the set of elliptic curves over K (i.e. the equation defining the curve has coefficients in K) up to isomorphism. We consider curves E1;E2 over K to be isomorphic if there is a map ': E1 ! E2 defined over K (meaning the coefficients of ' are in K). This is an example of a moduli problem. We begin by studying Ell(C). Elliptic curves over C have a particularly nice form: Proposition 1. For every elliptic curve E=C, there is a lattice ΛE ⊂ C and a complex analytic group 0 isomorphism C=ΛE ! E(C). Further, maps E ! E correspond to complex numbers α such that αΛE ⊂ ΛE0 . 0 In particular two elliptic curves E; E are isomorphic if and only if αΛE = ΛE0 for some α 2 C, i.e. if the lattices ΛE; ΛE0 are homothetic. -

The Klein Quartic in Number Theory

The Klein Quartic in Number Theory The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Elkies, Noam D. The Klein quartic in number theory. In The Eightfold Way: The Beauty of Klein's Quartic Curve, ed. Sylvio Levi, 51-102. Mathematical Sciences Research Institute publications, 35. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Published Version http://www.msri.org/publications/books/Book35/contents.html Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:2920120 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Eightfold Way MSRI Publications Volume 35, 1998 The Klein Quartic in Number Theory NOAM D. ELKIES Abstract. We describe the Klein quartic X and highlight some of its re- markable properties that are of particular interest in number theory. These include extremal properties in characteristics 2, 3, and 7, the primes divid- ing the order of the automorphism group of X; an explicit identification of X with the modular curve X(7); and applications to the class number 1 problem and the case n = 7 of Fermat. Introduction Overview. In this expository paper we describe some of the remarkable prop- erties of the Klein quartic that are of particular interest in number theory. The Klein quartic X is the unique curve of genus 3 over C with an automorphism group G of size 168, the maximum for its genus. -

Elliptic and Modular Curves Over Finite Fields and Related Computational

Elliptic and modular curves over finite fields and related computational issues Noam D. Elkies March, 1997 Based on a talk given at the conference Computational Perspectives on Number Theory in honor of A.O.L. Atkin held September, 1995 in Chicago Introduction The problem of calculating the trace of an elliptic curve over a finite field has attracted considerable interest in recent years. There are many good reasons for this. The question is intrinsically compelling, being the first nontrivial case of the natural problem of counting points on a complete projective variety over a finite field, and figures in a variety of contexts, from primality proving to arithmetic algebraic geometry to applications in secure communication. It is also a difficult but rewarding challenge, in that the most successful approaches draw on some surprisingly advanced number theory and suggest new conjectures and results apart from the immediate point-counting problem. It is those number-theoretic considerations that this paper addresses, specifi- cally Schoof’s algorithm and a series of improvements using modular curves that have made it practical to compute the trace of a curve over finite fields whose size is measured in googols. Around this main plot develop several subplots: other, more elementary approaches better suited to small fields; possible gener- alizations to point-counting on varieties more complicated than elliptic curves; further applications of our formulas for modular curves and isogenies. We steer clear only of the question of how to adapt our methods, which work most read- ily for large prime fields, to elliptic curves over fields of small characteristic; see [Ler] for recent work in this direction. -

Modular Forms: a Computational Approach William A. Stein

Modular Forms: A Computational Approach William A. Stein (with an appendix by Paul E. Gunnells) Department of Mathematics, University of Washington E-mail address: [email protected] Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Massachusetts E-mail address: [email protected] 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 11; Secondary 11-04 Key words and phrases. abelian varieties, cohomology of arithmetic groups, computation, elliptic curves, Hecke operators, modular curves, modular forms, modular symbols, Manin symbols, number theory Abstract. This is a textbook about algorithms for computing with modular forms. It is nontraditional in that the primary focus is not on underlying theory; instead, it answers the question “how do you explicitly compute spaces of modular forms?” v To my grandmother, Annette Maurer. Contents Preface xi Chapter 1. Modular Forms 1 1.1. Basic Definitions 1 § 1.2. Modular Forms of Level 1 3 § 1.3. Modular Forms of Any Level 4 § 1.4. Remarks on Congruence Subgroups 7 § 1.5. Applications of Modular Forms 9 § 1.6. Exercises 11 § Chapter 2. Modular Forms of Level 1 13 2.1. Examples of Modular Forms of Level 1 13 § 2.2. Structure Theorem for Level 1 Modular Forms 17 § 2.3. The Miller Basis 20 § 2.4. Hecke Operators 22 § 2.5. Computing Hecke Operators 26 § 2.6. Fast Computation of Fourier Coefficients 29 § 2.7. Fast Computation of Bernoulli Numbers 29 § 2.8. Exercises 33 § Chapter 3. Modular Forms of Weight 2 35 3.1. Hecke Operators 36 § 3.2. Modular Symbols 39 § 3.3. Computing with Modular Symbols 41 § vii viii Contents 3.4. -

Elliptic Curves and Modularity

Elliptic curves and modularity For background and (most) proofs, we refer to [1]. 1 Weierstrass models Let K be any field. For any a1; a2; a3; a4; a6 2 K consider the plane projective curve C given by the equation 2 2 3 2 2 3 y z + a1xyz + a3yz = x + a2x z + a4xz + a6z : (1) An equation as above is called a Weierstrass equation. We also say that (1) is a Weierstrass model for C. L-Rational points For any field extension L=K we can consider the L-rational points on C, i.e. the points on C with coordinates in L: 2 C(L) := f(x : y : z) 2 PL : equation (1) is satisfied g: The point at infinity The point O := (0 : 1 : 0) 2 C(K) is the only K-rational point on C with z = 0. It is always smooth. Most of the time we shall instead of a homogeneous Weierstrass equation write an affine Weierstrass equation: 2 3 2 C : y + a1xy + a3y = x + a2x + a4x + a6 (2) which is understood to define a plane projective curve. The discriminant Define 2 b2 := a1 + 4a2; b4 := 2a4 + a1a3; 2 b6 := a3 + 4a6; 2 2 2 b8 := a1a6 + 4a2a6 − a1a3a4 + a2a3 − a4: For any Weierstrass equation we define its discriminant 2 3 2 ∆ := −b2b8 − 8b4 − 27b6 + 9b2b4b6: 1 Note that if char(K) 6= 2, then we can perform the coordinate transformation 2 3 2 y 7! (y − a1x − a3)=2 to arrive at an equation y = 4x + b2x + 2b4x + b6. The discriminant (w.r.t.