Transforming Policy and Politics: the Future of the State in the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGMA Decisions Agreed 24 November 2017 FINAL, Item 3F PDF

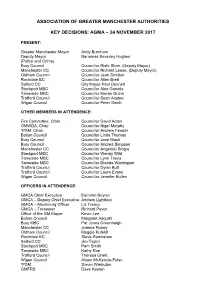

ASSOCIATION OF GREATER MANCHESTER AUTHORITIES KEY DECISIONS: AGMA – 24 NOVEMBER 2017 PRESENT: Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham Deputy Mayor Baroness Beverley Hughes (Police and Crime) Bury Council Councillor Rishi Shori, (Deputy Mayor) Manchester CC Councillor Richard Leese, (Deputy Mayor) Oldham Council Councillor Jean Stretton Rochdale BC Councillor Allen Brett Salford CC City Mayor Paul Dennett Stockport MBC Councillor Alex Ganotis Tameside MBC Councillor Kieran Quinn Trafford Council Councillor Sean Anstee Wigan Council Councillor Peter Smith OTHER MEMBERS IN ATTENDENCE: Fire Committee, Chair Councillor David Acton GMWDA, Chair Councillor Nigel Murphy TfGM, Chair, Councillor Andrew Fender Bolton Council Councillor Linda Thomas Bury Council Councillor Jane Black Bury Council Councillor Andrea Simpson Manchester CC Councillor Angelicki Stogia Stockport MBC Councillor Wendy Wild Tameside MBC Councillor Lynn Travis Tameside MBC Councillor Brenda Warrington Trafford Council Councillor Dylan Butt Trafford Council Councillor Laura Evans Wigan Council Councillor Jennifer Bullen OFFICERS IN ATTENDENCE: GMCA Chief Executive Eamonn Boylan GMCA – Deputy Chief Executive Andrew Lightfoot GMCA – Monitoring Officer Liz Treacy GMCA – Treasurer Richard Paver Office of the GM Mayor Kevin Lee Bolton Council Margaret Asquith Bury MBC Pat Jones Greenhalgh Manchester CC Joanne Roney Oldham Council Maggie Kufeldt Rochdale BC Steve Rumbelow Salford CC Jim Taylor Stockport MBC Pam Smith Tameside MBC Kathy Roe Trafford Council Theresa Grant Wigan Council Alison McKenzie-Folan TfGM Simon Warbuton GMFRS Dave Keelan Manchester Growth Co Mark Hughes GMCA Julie Connor GMCA Lindsay Dunn GMCA Simon Nokes GMCA Emma Stonier GMCA Sylvia Welsh APOLOGIES: Bolton Council Councillor Cliff Morris Oldham Council Carolyn Wilkins Rochdale BC Councillor Richard Farnell Tameside MBC Steven Pleasant Wigan Council Donna Hall GMP Ian Hopkins GMHSC Partnership Jon Rouse TfGM Jon Lamonte Agenda Item No. -

Let's Not Go Back to 70S Primary Education Wikio

This site uses cookies to help deliver services. By using this site, you agree to the use of cookies. Learn more Got it Conor's Commentary A blog about politics, education, Ireland, culture and travel. I am Conor Ryan, Dublin-born former adviser to Tony Blair and David Blunkett on education. Views expressed on this blog are written in a personal capacity. Friday, 20 February 2009 SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE UPDATES Let's not go back to 70s primary education Wikio Despite the Today programme's insistence on the term, "independent" is certainly not an apt Contact me description of today's report from the self-styled 'largest' review of primary education in 40 years. It You can email me here. is another deeply ideological strike against standards and effective teaching of the 3Rs in our primary schools. Many of its contributors oppose the very idea of school 'standards' and have an ideological opposition to external testing. They have been permanent critics of the changes of recent decades. And it is only in that light that the review's conclusions can be understood. Of course, there is no conflict between teaching literacy and numeracy, and the other subjects within the primary curriculum. And the best schools do indeed show how doing them all well provides a good and rounded education. Presenting this as the point of difference is a diversionary Aunt Sally. However, there is a very real conflict between recognising the need to single literacy and numeracy out for extra time over the other subjects as with the dedicated literacy and numeracy lessons, and making them just another aspect of primary schooling that pupils may or may not pick up along the way. -

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009 This note provides details of the Cabinet and Ministerial reshuffle carried out by the Prime Minister on 5 June following the resignation of a number of Cabinet members and other Ministers over the previous few days. In the new Cabinet, John Denham succeeds Hazel Blears as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and John Healey becomes Housing Minister – attending Cabinet - following Margaret Beckett’s departure. Other key Cabinet positions with responsibility for issues affecting housing remain largely unchanged. Alistair Darling stays as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Mandelson at Business with increased responsibilities, while Ed Miliband continues at the Department for Energy and Climate Change and Hilary Benn at Defra. Yvette Cooper has, however, moved to become the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions with Liam Byrne becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills has been merged with BERR to create a new Department for Business, Innovation and Skills under Lord Mandelson. As an existing CLG Minister, John Healey will be familiar with a number of the issues affecting the industry. He has been involved with last year’s Planning Act, including discussions on the Community Infrastructure Levy, and changes to future arrangements for the adoption of Regional Spatial Strategies. HBF will be seeking an early meeting with the new Housing Minister. A full list of the new Cabinet and other changes is set out below. There may yet be further changes in junior ministerial positions and we will let you know of any that bear on matters of interest to the industry. -

Lobby Programme Emphasis in 2008 Keep Our Future Afloat Campaign

Keep our Future Afloat 2008 Lobby programme emphasis in 2008 • Continuing to influence all political parties and shipbuilding industry leaders. • Meeting with the new Defence Procurement Minister, Baroness Taylor at the earliest opportunity. • Drawing attention to potential workload gaps and implications for production and design skills retention. • Securing orders for Barrow’s core expertise submarines, 7 Astute class. The UK needs a fleet that can surge in times of crisis, 4, 5 or 6 are not enough. • Highlighting Barrow’s role in the successor submarine (Vanguard replacement) programme and the need to proceed with the replacement deterrent fleet. • Promoting Barrow’s core competency and role in delivering nuclear submarines. • Highlighting Barrow’s role in building the Future Aircraft Carriers. • Seeking a role for Barrow in the MARS programme. • Publishing a lobby paper highlighting the benefits of the UK nuclear power station programme as a means of creating diversification opportunities for UK shipyards, a way of sustaining key nuclear skills and of enhancing the implementation of the Defence Industrial Strategy requirement to sustain key capabilities and promote opportunity for civil nuclear reactor build being undertaken in the UK instead of overseas. • Supporting BAE SYSTEMS diversification moves, particularly into nuclear and upstream oil and gas. • Ensuring that overseas shipyards do not gain a share of the market at the expense of Barrow and support build of warlike ships in UK not EU. • Securing MoD clarification of what it regards as ‘complex’ and ‘less complex’ naval ships which are not defined in the Defence Industrial Strategy. • Helping implement the new Defence Industrial Strategy. -

Decennium 7/7 the United Kingdom Terrorist Attacks on July 7, 2005, and the Evolution of Anti-Terrorism Policies, Laws, and Practices

Decennium 7/7 The United Kingdom terrorist attacks on July 7, 2005, and the evolution of anti-terrorism policies, laws, and practices By Prof. Dr. Dr. Clive Walker , Leeds I. Introduction might be termed ‘neighbour terrorism’ 5 has taken centre- 6 The tenth anniversary (the Decennium) of the 7 July 2005, stage rather than terrorism from alien sources. London transport bombings provides a poignant but appro- The human and material wreckage of 7/7 was also the priate juncture at which to reflect upon the lessons learned catalyst for signalling major changes in the long history of from those coordinated and severe terrorist attacks. 1 The United Kingdom counter-terrorism policy and laws. A com- killing of 52 civilians by four ‘home-grown’ extremists, who prehensive strategy, entitled CONTEST, which had been prepared in secret by 2003, 7 was finally unveiled to the public had been inspired by the violent ideology of Al Qa’ida, 8 marked the worst terrorist atrocity in the United Kingdom in 2006. The strategy includes the traditional approaches of since the Lockerbie air disaster of 1988. 2 The seminal im- ‘Pursuit’ (policing and criminal justice tactics). Protective portance of 7/7 resides in both the nature of the attack and the security (dubbed ‘Prepare’ and ‘Protect’) is also highlighted, official response, both marking a transition to a new, but not and this element builds on the Promethean and expensive duties of planning and resilience established in the Civil wholly distinct, stage of United Kingdom terrorism and coun- 9 ter-terrorism. Contingencies Act 2004. However, CONTEST also address- As for the nature of the terrorism, the characteristics of ji- es the more pioneering and problematic agenda of ‘Prevent’ – hadi terrorism, 3 with its vaulting ambitions, strident ideology ‘tackling disadvantage and supporting reform […] deterring those who facilitate terrorism and those who encourage oth- and disregard for civilian casualties signified new challenges 10 for the state authorities and public alike. -

The Crisis of the Democratic Left in Europe

The crisis of the democratic left in Europe Denis MacShane Published by Progress 83Victoria Street, London SW1H 0HW Tel: 020 3008 8180 Fax: 020 3008 8181 Email: [email protected] www.progressonline.org.uk Progress is an organisation of Labour party members which aims to promote a radical and progressive politics for the 21st century. We seek to discuss, develop and advance the means to create a more free, equal and democratic Britain, which plays an active role in Europe and the wider the world. Diverse and inclusive, we work to improve the level and quality of debate both within the Labour party, and between the party and the wider progressive communnity. Honorary President : Rt Hon Alan Milburn MP Chair : StephenTwigg Vice chairs : Rt Hon Andy Burnham MP, Chris Leslie, Rt Hon Ed Miliband MP, Baroness Delyth Morgan, Meg Munn MP Patrons : Rt Hon Douglas Alexander MP, Wendy Alexander MSP, Ian Austin MP, Rt Hon Hazel Blears MP, Rt HonYvette Cooper MP, Rt Hon John Denham MP, Parmjit Dhanda MP, Natascha Engel MP, Lorna Fitzsimons, Rt Hon Peter Hain MP, John Healey MP, Rt Hon Margaret Hodge MP, Rt Hon Beverley Hughes MP, Rt Hon John Hutton MP, Baroness Jones, Glenys Kinnock MEP, Sadiq Kahn MP, Oona King, David Lammy MP, Cllr Richard Leese,Rt Hon Peter Mandelson, Pat McFadden MP, Rt Hon David Miliband MP,Trevor Phillips, Baroness Prosser, Rt Hon James Purnell MP, Jane Roberts, LordTriesman. Kitty Ussher MP, Martin Winter Honorary Treasurer : Baroness Margaret Jay Director : Robert Philpot Deputy Director : Jessica Asato Website and Communications Manager :Tom Brooks Pollock Events and Membership Officer : Mark Harrison Publications and Events Assistant : EdThornton Published by Progress 83 Victoria Street, London SW1H 0HW Tel: 020 3008 8180 Fax: 020 3008 8181 Email: [email protected] www.progressives.org.uk 1 . -

Ministers Reflect Jim Knight

Ministers reflect Jim Knight May 2016 2 Jim Knight – biographical details Electoral History 2010-present: Labour Member of the House of Lords 2001-2010: Member of Parliament for South Dorset Parliamentary Career 2011-2014: Shadow Spokesperson (Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) 2010-2011: Shadow Spokesperson (Work and Pensions) 2009-2010: Minister of State for Employment and Welfare Reform 2009-2010: Minister of State for the South West 2006-2009: Minister of State for Schools and Learners 2005-2006: Parliamentary Under-Secretary (Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) 3 Jim Knight Jim Knight was interviewed by Nicola Hughes and Catherine Haddon on 28th April 2016 for the Institute for Government’s Ministers Reflect Project. Nicola Hughes (NH): So if we can start back when you very first started as a minister, do you remember much of what your experience of coming into government was like? Jim Knight (JK): Yeah, well I remember things. I haven’t wiped it completely clean! So I was appointed to Defra [Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs] and as then subsequently was the way, when I was appointed to [the Department for] Education, the first thing I found out about was that I had a bill straight away. I had a Secretary of State in the form of Margaret Beckett who was quite hands off, was clear about what she wanted, and regular and effective and very inclusive ministerial meetings, but I think I only had one one-to-one with her in the whole year that I was working with her, which I took as an endorsement of trust and so on. -

Tittle-Tattle (Summer 2010)

Lobster 59 Tittle-tattle Tom Easton The fall of St David The departure of the Lib-Con government’s Chief Secretary to the Treasury, David Laws, must cause a little alarm to other ministers whose expense records are held by The Daily Telegraph. Will their own financial affairs be revealed at critical times for the new coalition, they must be wondering. But for Laws, the co-editor of the Lib Dems’ Orange Book, who set himself up for a political career in Lord Ashdown’s old Yeovil seat after making a pile with JP Morgan and Barclays de Zoete Wedd, the press coverage was broadly sympathetic. Most of the media support the coalition, and so while accepting he had to go after the revelation of the £40,000 rent payment from the taxpayer, most still think he can a make a ministerial return following the New Labour precedents of Peter Mandelson, David Blunkett, Beverley Hughes and Peter Hain. Some journalists went further in their support for Laws. While his partner Matthew Parris was touring the studios urging Laws to stay on, Guardian columnist Julian Glover wrote twice in two days in support of the Yeovil MP. Before his departure Glover wrote: ‘The story of David Laws has an uncomfortable echo: the downfall of BP’s former chief executive John Browne.’ After he went, Glover described Laws as ‘this man of exceptional nobility’. Readers who want to assess Glover’s comparison with Lord Browne may care to read the judgment in that case of Mr Justice Eady, a man not known for upholding the press’s right 86 Summer 2010 to free expression in privacy matters.1 Those who want to weigh the ‘exceptional nobility’ of the former Chief Secretary, ‘Mr Integrity’, according to Ashdown, might start with this – <www.yeovil-libdems.org.uk/news/press/1305.htm> – from his recent Yeovil election campaign. -

Labour Party Annual Report 2020 3 CONTENTS

LABOUR PARTY ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 2 0 Labour Party Annual Report 2020 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION LABOUR PARTY MANAGEMENT . 45 Foreword from Keir Starmer . 5 Human Resources Report . 46 Introduction from Angela Rayner . 7 Introduction from the General Secretary . 8 2019/2020 National Executive Committee . 10 STABILITY IN OUR FINANCES . 49 NEC Committees . 13 Finances . 50 Obituaries . 14 Fundraising: NEC aims and objectives for 2020 . 15 fundraising and The Rose Network . 51 Events and Endorsements 2019/20: events, exhibitions, annual conference . 52 GENERAL ELECTION . 17 Donations, including sponsorship over £7 .5k . 55 2019 General Election . 18 Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 December 2019 . 56 PARLIAMENTARY BY-ELECTIONS . 25 Statement of Registered Brecon and Radnorshire . 26 Treasurer’s responsibilities . 57 LOOKING AHEAD: 2021 ELECTIONS . 27 APPENDICES . 81 Local and Mayoral Elections 2021 . 28 Members of Shadow Cabinet The year ahead in Scotland . 30 and Opposition Frontbench . 82 The year ahead in Wales . 31 Parliamentary Labour Party . 86 Members of the Scottish Parliament. 92 MEMBERS AND SUPPORTERS . 33 Members of the Welsh Parliament . 93 Building an active membership Members of the London Assembly . 94 and supporters network . 34 Directly Elected Mayors . 95 Equalities: Winning with Women; Leaders of Labour Groups . 96 BAME Labour; LGBT+ Labour; Labour Peers . 104 Disability Labour; Young Labour . 35 Labour Police and Crime Commissioners . 103 Parliamentary Candidates endorsed by the NEC at time of publication . 107 POLICY MAKING . 39 NEC Disputes . 108 National Policy Forum . 40 NCC Cases . 109 INTERNATIONAL . 43 International work/ Westminster Foundation for Democracy . 44 Labour Party Annual Report 2020 3 Introduction FOREWORD KEIR STARMER It is the honour of my life to lead our great running the Organise to Win review, and a movement . -

LGIU Local Government Information Unit

Ministerial, Shadow and regional responsibilities July 2007 - LGIU Page 1 of 5 LGIU Local Government Information Unit Independent Intelligent Information Ministerial, Shadow and regional responsibilities July 2007 (LGIUandSTEER) 9/7/2007 Author: Hilary Kitchin Reference No: PB 1526/07L This covers: England and Wales Overview This briefing provides an outline of new ministerial and shadow responsibilities in Communities and Local Government. There is as yet no timetable for publication of ministers' full range of responsibilities. Ministerial biographies of the DCLG team and and the names of ministers with regional responsibilities are set out in the main part of the briefing. Ministerial team at the Department for Communities and Local Government Secretary of State: The Right Hon Hazel Blears MP Minister of State - Yvette Cooper MP - housing Minister of State - John Healey MP - local government Parliamentary Under Secretary of State - Baroness Andrews OBE Parliamentary Under Secretary of State - Parmjit Dhanda MP - cohesion and neighbourhoods Parliamentary Under Secretary of State - Iain Wright MP - planning Special advisors to Hazel Blears: Paul Richards and Andy Bagnall, former councillors at Lewisham and Croydon respectively. Opposition changes of direct relevance to local government: Conservative Party responsibilities: Eric Pickles MP will replace Caroline Spelman MP as Shadow Communities Secretary. The front bench team is made up of MPs Grant Shapps, Alistair Burt, Paul Goodman, Bob Neil, and Jacqui Lait. Sayeeda Warsi, currently a Vice Chairman of the Party, will be given a peerage to take up a role as Shadow Minister for Community Cohesion http://www.lgiu.gov.uk/briefing-detail.jsp?&id=1526&md=0§ion=briefing 09/07/2007 Ministerial, Shadow and regional responsibilities July 2007 - LGIU Page 2 of 5 Liberal Democrat responsibilities: Andrew Stunell MP retains his position as Shadow Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government. -

A Case to Answer

A Case to Answer A first report on the potential impeachment of the Prime Minister for High Crimes and Misdemeanours in relation to the invasion of Iraq. Produced for Adam Price MP August 2004 www.impeachBlair.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. First published in August 2004 by Adam Price MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA Printed by Kinko’s Limited 1 Curzon Street London W1Y 7FN A Case to Answer A first report on the potential impeachment of the Prime Minister for High Crimes and Misdemeanours in relation to the invasion of Iraq. Produced for Adam Price MP Authors Chapter I: Glen Rangwala and Dan Plesch Chapter II: Dan Plesch With the assistance of Ffion Evans, John Fellows and Gwenllian Griffiths Glen Rangwala is a lecturer in politics at Newnham College, Cambridge. Dan Plesch is an Honorary Fellow of Birkbeck College, University of London and a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the University of Keele. He is the author of the recently published The Beauty Queens’ Guide to World Peace. Foreword This report sets out compelling evidence of deliberate repeated distortion, seriously misleading statements and culpable negligence on the part of the Prime Minister. This misconduct is in itself more than sufficient to require his resignation. Further to this, the Prime Minister’s conduct has also destroyed the United Kingdom’s reputation for honesty around the world; it has produced a war with no end in sight; it has damaged and discredited the intelligence services which are essential to the security of the state; it has undermined the constitution by weakening cabinet government to breaking point and it has made a mockery of the authority of Parliament as representatives of the people. -

Gordon Brown's Ministers

Gordon Brown’s ministers What do they do? What do they earn? The new cabinet is in place. Competing claims for promo- Secretary of state Parliamentary under secretary of Prime minister Minister of state (Lord) Cabinet minister in charge of a state £188,848 £81,504 tion — and survival — have been squared, something all government department (although Junior minister and not a member incoming prime ministers must do. Deals have been HM Treasury is headed by the of cabinet — although they may be Secretary of state Parliamentary secretary: (MP) struck on who remains a minister of state, or gets quietly Chancellor of the Exchequer) members of a cabinet committee £137,579 £90,954 dropped, and what fresh talent climbs the first rung of Permanent secretary: Parliamentary private secretary Solicitor general Parliamentary secretary: (Lord) Most senior civil servant in a Unpaid junior position in which MP £127,683 £70,986 office as an under secretary. In new departments cabinet government department, and runs acts as the parliamentary eyes and Attorney general Salaries include MP’s basic pay of ministers must get to know the civil servant whose coop- it on a day-to-day basis ears for a senior minister. Officially £109,201 £60,675 eration may be crucial to success, their permanent secre- not members of government Minister of state Minister of state (MP) tary, but also choose special advisers to be their political Junior to the secretary of state but senior to a parliamentary under £100,567 eyes and ears. Seventeen men and five women must secretary of state and parliamen- absorb hours of expert policy briefing and mountains of tary private secretaries paper.