A Case to Answer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan

Nxxx,2009-09-05,A,009,Bs-BW,E3 THE NEW YORK TIMES INTERNATIONAL SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2009 ØØN A9 NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan governor of Ali Abad, Hajji Habi- From Page A1 bullah, said the area was con- with the Afghan people.” trolled by Taliban commanders. Two 14-year-old boys and one The Kunduz area was once 10-year-old boy were admitted to calm, but much of it has recently the regional hospital here in Kun- slipped under the control of in- duz, along with a 16-year-old who surgents at a time when the Oba- later died. Mahboubullah Sayedi, ma administration has sent thou- a spokesman for the Kunduz pro- sands of more troops to other vincial governor, said most of the parts of the country to combat an estimated 90 dead were militants, insurgency that continues to gain judging by the number of charred strength in many areas. pieces of Kalashnikov rifles The region is patrolled mainly found. But he said civilians were by NATO’s 4,000-member Ger- also killed. man force, which is barred by In explaining the civilian German leaders from operating deaths, military officials specu- in combat zones farther south. lated that local people were con- The United States has 68,000 scripted by the Taliban to unload troops in Afghanistan, more than the fuel from the tankers, which any other nation; other countries were stuck near a river several fighting under the NATO com- miles from the nearest villages. mand have a combined total of about 40,000 troops here. -

Intelligence Ethics 2007.Pdf

Intelligence Ethics: The Definitive Work of 2007* Published by the Center for the Study of Intelligence and Wisdom Edited by Michael Andregg About the Eyes A spy asked, “Why the eyes?” They are the eyes of my daughter, who deserves a decent world to grow up in. They are the eyes of your mother, who deserves a decent peace to grow old in. They are the eyes of children blown to shreds by PGMs sent to the wrong address by faulty intelligence. And they are the eyes of children blown to shreds by suicide bombers inspired by faulty intelligence. They are the eyes of orphans and they are the eyes of God, wondering who fears ethical thought and why. Grandmother says it is time to grow up. The nation is in danger and the children are in peril. So sometimes you can set long books of rules aside and use the ancient Grandma Test. If she were watching, and knew everything you do, would she really approve? Copyright © 2007 by Michael Murphy Andregg All rights reserved. Published in the United States by the Center for the Study of Intelligence and Wisdom, an imprint of Ground Zero Minnesota in St. Paul, Minnesota, USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Andregg, Michael M. ISBN 0-9773-8181-1 1. Ethics. 2. Intelligence Studies. 3. Human Survival. Printed in the United States of America First Edition A generic Disclaimer : Many of our authors have had diverse and interesting government backgrounds and some are still on active duty. Others are professors of intelligence studies with active security clearances. -

Investigatory Inquiries and the Inquiries Act 2005

Investigatory inquiries and the Inquiries Act 2005 Standard Note: SN/PC/02599 Last updated: 19 July 2011 Author: Chris Sear Section Parliament and Constitution Centre The Inquiries Act 2005 made significant changes to the system of public inquiries in the UK including the repeal of the Tribunals of Inquiry (Evidence) Act 1921 which had formed the main basis for statutory inquiries over some 80 years. The 2005 Act provides a statutory framework for inquiries into matters of public concern, and this note list the inquiries established under the Inquiries Act 2005 and, provides some assessments of the impact of the Act. This note does not encompass routine administrative inquiries into, for example, planning or social security matters, nor specialist inquiries such as transport accident or companies act investigations. It does however discuss some alternative ways of establishing inquiries into matters of public concern, other than those set up under the 2005 Act, as well as some of the issues raised by public inquiries such as the need to keep the cost of inquiries under control. This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for it. A suitably qualified professional should be consulted if specific advice or information is required. This information is provided subject to our general terms and conditions which are available online or may be provided on request in hard copy. -

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry: Executive Summary

Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons dated 6 July 2016 for The Report of the Iraq Inquiry Executive Summary Report of a Committee of Privy Counsellors Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 6 July 2016 HC 264 46561_00b Viking_Executive Summary Title Page.indd 1 23/06/2016 14:22 © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identifi ed any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] Print ISBN 9781474133319 Web ISBN 9781474133326 ID 23051602 46561 07/16 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fi bre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Offi ce 46561_00b Viking_Executive Summary Title Page.indd 2 23/06/2016 14:22 46561_00c Viking_Executive Summary.indd 1 23/06/2016 15:04 46561_00c Viking_Executive Summary.indd 2 23/06/2016 14:17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 Pre‑conflict strategy and planning .................................................................................... 5 The UK decision to support US military action ................................................................. 6 UK policy before 9/11 ................................................................................................ -

Party Conferences Programme 2010

PARTY CONFERENCES PROGRAMME 2010 Liberal Democrat Party Conference 19—21 September p.! Labour Party Conference 26—29 September p." Conservative Party Conference 3—6 October p.# Liberal Democrat Party Conference ! SUNDAY 19 SEPTEMBER 13.00—14.00 / Suite 8 / Jury’s Inn Child-friendly communities: Tackling child poverty at the local level Sarah Teather MP; Anita Tiessen, UNICEF UK; David Powell, Dorset County Council; A young person involved with Child Friendly Communities; Decca Aitkenhead, The Guardian (Chair) 18.15—19.30 / Suite 6 / Jury’s Inn !e Demos Grill: An in-conversation Vince Cable MP, Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills; Danny Finkelstein, The Times 18.15—19.30 / ACC Liverpool / Hall 11C Public service reform in an age of cuts: Where next? Paul Burstow MP (invited); Ben Lucas, 2020 Public Services Trust (invited); Stephen Bubb, ACEVO; Roy O’Shaughnessy, CDG; Randeep Ramesh, The Guardian (Chair); MONDAY 20 SEPTEMBER 8.00—9.00 / Holiday Inn Express / Albert Dock / Britannia 1 Tackling Britain’s worklessness: How to get the Work Programme working Lord German; Jill Kirby, Centre for Policy Studies (invited); Mark Lovell, A4e; Allegra Stratton, The Guardian (Chair) By invitation only 8.00—9.30 / Hilton Liverpool / Meeting Room 6—7 Learning to Succeed: Building culture and ethos in challenging schools Duncan Hames MP; Daisy Christodoulou, Teach First; Professor Dylan Wiliam, Institute of Education, University of London; Chris Kirk, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP; Philip Collins, Demos (Chair) By invitation only 13.00—14.00 / Blue Bar / Albert Dock Tackling child poverty in an age of austerity Sarah Teather MP; Kate Stanley, ippr; Sally Copley, Save the Children; Philip Collins, Demos (Chair) Liberal Democrat Party Conference cont. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

Mr Blair's Poodle Goes To

Mr Blair’s Poodle goes to War The House of Commons, Congress and Iraq ANDREW TYRIE MP CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street, London SW1P 3QL 2004 THE AUTHOR ANDREW TYRIE has been Conservative Member of Parliament for Chichester since May 1997. His publications include A Cautionary Tale of EMU (CPS, 1991); The Prospects for Public Spending (Social Market Foundation, 1996); Reforming the Lords: a Conservative approach (Conservative Policy Forum, 1998); Leviathan at Large: the new regulator for the financial markets (with Martin McElwee, CPS, 2000); Mr Blair’s Poodle: an agenda for reviving the House of Commons (CPS, 2000); Back from the Brink (Parliamentary Mainstream, 2001); Statism by Stealth: new Labour, new collectivism (CPS, 2002); and Axis of Instability: America, Britain and The New World Order after Iraq (The Foreign Policy Centre and the Bow Group, 2003). The aim of the Centre for Policy Studies is to develop and promote policies that provide freedom and encouragement for individuals to pursue the aspirations they have for themselves and their families, within the security and obligations of a stable and law-abiding nation. The views expressed in our publications are, however, the sole responsibility of the authors. Contributions are chosen for their value in informing public debate and should not be taken as representing a corporate view of the CPS or of its Directors. The CPS values its independence and does not carry on activities with the intention of affecting public support for any registered political party or for candidates at election, or to influence voters in a referendum. ISBN No. -

AGMA Decisions Agreed 24 November 2017 FINAL, Item 3F PDF

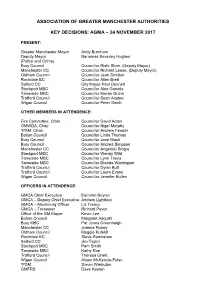

ASSOCIATION OF GREATER MANCHESTER AUTHORITIES KEY DECISIONS: AGMA – 24 NOVEMBER 2017 PRESENT: Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham Deputy Mayor Baroness Beverley Hughes (Police and Crime) Bury Council Councillor Rishi Shori, (Deputy Mayor) Manchester CC Councillor Richard Leese, (Deputy Mayor) Oldham Council Councillor Jean Stretton Rochdale BC Councillor Allen Brett Salford CC City Mayor Paul Dennett Stockport MBC Councillor Alex Ganotis Tameside MBC Councillor Kieran Quinn Trafford Council Councillor Sean Anstee Wigan Council Councillor Peter Smith OTHER MEMBERS IN ATTENDENCE: Fire Committee, Chair Councillor David Acton GMWDA, Chair Councillor Nigel Murphy TfGM, Chair, Councillor Andrew Fender Bolton Council Councillor Linda Thomas Bury Council Councillor Jane Black Bury Council Councillor Andrea Simpson Manchester CC Councillor Angelicki Stogia Stockport MBC Councillor Wendy Wild Tameside MBC Councillor Lynn Travis Tameside MBC Councillor Brenda Warrington Trafford Council Councillor Dylan Butt Trafford Council Councillor Laura Evans Wigan Council Councillor Jennifer Bullen OFFICERS IN ATTENDENCE: GMCA Chief Executive Eamonn Boylan GMCA – Deputy Chief Executive Andrew Lightfoot GMCA – Monitoring Officer Liz Treacy GMCA – Treasurer Richard Paver Office of the GM Mayor Kevin Lee Bolton Council Margaret Asquith Bury MBC Pat Jones Greenhalgh Manchester CC Joanne Roney Oldham Council Maggie Kufeldt Rochdale BC Steve Rumbelow Salford CC Jim Taylor Stockport MBC Pam Smith Tameside MBC Kathy Roe Trafford Council Theresa Grant Wigan Council Alison McKenzie-Folan TfGM Simon Warbuton GMFRS Dave Keelan Manchester Growth Co Mark Hughes GMCA Julie Connor GMCA Lindsay Dunn GMCA Simon Nokes GMCA Emma Stonier GMCA Sylvia Welsh APOLOGIES: Bolton Council Councillor Cliff Morris Oldham Council Carolyn Wilkins Rochdale BC Councillor Richard Farnell Tameside MBC Steven Pleasant Wigan Council Donna Hall GMP Ian Hopkins GMHSC Partnership Jon Rouse TfGM Jon Lamonte Agenda Item No. -

Let's Not Go Back to 70S Primary Education Wikio

This site uses cookies to help deliver services. By using this site, you agree to the use of cookies. Learn more Got it Conor's Commentary A blog about politics, education, Ireland, culture and travel. I am Conor Ryan, Dublin-born former adviser to Tony Blair and David Blunkett on education. Views expressed on this blog are written in a personal capacity. Friday, 20 February 2009 SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE UPDATES Let's not go back to 70s primary education Wikio Despite the Today programme's insistence on the term, "independent" is certainly not an apt Contact me description of today's report from the self-styled 'largest' review of primary education in 40 years. It You can email me here. is another deeply ideological strike against standards and effective teaching of the 3Rs in our primary schools. Many of its contributors oppose the very idea of school 'standards' and have an ideological opposition to external testing. They have been permanent critics of the changes of recent decades. And it is only in that light that the review's conclusions can be understood. Of course, there is no conflict between teaching literacy and numeracy, and the other subjects within the primary curriculum. And the best schools do indeed show how doing them all well provides a good and rounded education. Presenting this as the point of difference is a diversionary Aunt Sally. However, there is a very real conflict between recognising the need to single literacy and numeracy out for extra time over the other subjects as with the dedicated literacy and numeracy lessons, and making them just another aspect of primary schooling that pupils may or may not pick up along the way. -

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009 This note provides details of the Cabinet and Ministerial reshuffle carried out by the Prime Minister on 5 June following the resignation of a number of Cabinet members and other Ministers over the previous few days. In the new Cabinet, John Denham succeeds Hazel Blears as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and John Healey becomes Housing Minister – attending Cabinet - following Margaret Beckett’s departure. Other key Cabinet positions with responsibility for issues affecting housing remain largely unchanged. Alistair Darling stays as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Mandelson at Business with increased responsibilities, while Ed Miliband continues at the Department for Energy and Climate Change and Hilary Benn at Defra. Yvette Cooper has, however, moved to become the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions with Liam Byrne becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills has been merged with BERR to create a new Department for Business, Innovation and Skills under Lord Mandelson. As an existing CLG Minister, John Healey will be familiar with a number of the issues affecting the industry. He has been involved with last year’s Planning Act, including discussions on the Community Infrastructure Levy, and changes to future arrangements for the adoption of Regional Spatial Strategies. HBF will be seeking an early meeting with the new Housing Minister. A full list of the new Cabinet and other changes is set out below. There may yet be further changes in junior ministerial positions and we will let you know of any that bear on matters of interest to the industry. -

H-Diplo/ISSF Roundtable, Vol. 3, No. 16 (2012)

H-Diplo | ISSF Roundtable, Volume III, No. 17 (2012) A production of H-Diplo with the journals Security Studies, International Security, Journal of Strategic Studies, and the International Studies Association’s Security Studies Section (ISSS). http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/ISSF | http://www.issforum.org Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse, H-Diplo/ISSF Editors George Fujii, H-Diplo/ISSF Web and Production Editor Introduction by Jack S. Levy, Rutgers University Joshua Rovner. Fixing the Facts: National Security and the Politics of Intelligence. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011. ISBN: 978-0-8014-4829-4 (hardcover, $35.00). Published by H-Diplo/ISSF on 9 July 2012 Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/ISSF/PDF/ISSF-Roundtable-3-17.pdf Contents Introduction by Jack S. Levy, Rutgers University ...................................................................... 2 Review by Uri Bar-Joseph, Haifa University .............................................................................. 9 Review by Philip H.J. Davies, Brunel University ...................................................................... 16 Review by Michael S. Goodman, Department of War Studies, King’s College London ......... 21 Review by Keren Yarhi-Milo, Princeton University ................................................................. 24 Author’s Response by Joshua Rovner, Department of Strategy and Policy, U.S. Naval War College ..................................................................................................................................... 29 Copyright © 2012 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for nonprofit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author, web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For any other proposed use, contact the H-Diplo Editors at [email protected] H-Diplo/ISSF Roundtable Reviews, Vol. III, No. 17 (2012) Introduction by Jack S. -

Lobby Programme Emphasis in 2008 Keep Our Future Afloat Campaign

Keep our Future Afloat 2008 Lobby programme emphasis in 2008 • Continuing to influence all political parties and shipbuilding industry leaders. • Meeting with the new Defence Procurement Minister, Baroness Taylor at the earliest opportunity. • Drawing attention to potential workload gaps and implications for production and design skills retention. • Securing orders for Barrow’s core expertise submarines, 7 Astute class. The UK needs a fleet that can surge in times of crisis, 4, 5 or 6 are not enough. • Highlighting Barrow’s role in the successor submarine (Vanguard replacement) programme and the need to proceed with the replacement deterrent fleet. • Promoting Barrow’s core competency and role in delivering nuclear submarines. • Highlighting Barrow’s role in building the Future Aircraft Carriers. • Seeking a role for Barrow in the MARS programme. • Publishing a lobby paper highlighting the benefits of the UK nuclear power station programme as a means of creating diversification opportunities for UK shipyards, a way of sustaining key nuclear skills and of enhancing the implementation of the Defence Industrial Strategy requirement to sustain key capabilities and promote opportunity for civil nuclear reactor build being undertaken in the UK instead of overseas. • Supporting BAE SYSTEMS diversification moves, particularly into nuclear and upstream oil and gas. • Ensuring that overseas shipyards do not gain a share of the market at the expense of Barrow and support build of warlike ships in UK not EU. • Securing MoD clarification of what it regards as ‘complex’ and ‘less complex’ naval ships which are not defined in the Defence Industrial Strategy. • Helping implement the new Defence Industrial Strategy.