PAYING for the CREDIT CRUNCH Sharing the Proceeds of Thrift

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Observable Party Cohesion on Voter Choice in Liberal Democracies

PhD in Political Science The effect of observable party cohesion on voter choice in liberal democracies. Candidate David Jack Barrett Supervisor Michael Gallagher September 2017 2 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. Date Signature 3 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the help of a large number of people, and I would like to take the opportunity to express my thanks and gratitude to them. First, my supervisor Michael Gallagher has truly been extraordinarily helpful, providing comments and feedback at every point in the last four years, often at quite short notice. His encouragement and advice both on this thesis, but also in teaching and to attending conferences has always been wonderful. Certainly no one could have asked for a more patient and forgiving supervisor. This thesis would have been impossible without the financial support provided by the Irish Research Council (IRC) and by the Department of Political Science at Trinity College Dublin. My work is deeply in the debt of many scholars. James Davidson in the University of Exeter though, especially, provided me with much of the data used in Chapter Five in this thesis that he had gathered for his own research, and answered my endless questions regarding it, without which this research would have been impossible. -

Poverty and Philanthropy in the East

KATHARINE MARIE BRADLEY POVERTY AND PHILANTHROPY IN EAST LONDON 1918 – 1959: THE UNIVERSITY SETTLEMENTS AND THE URBAN WORKING CLASSES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD IN HISTORY CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF LONDON The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between the university settlements and the East London communities through an analysis their key areas of work during the period: healthcare, youth work, juvenile courts, adult education and the arts. The university settlements, which brought young graduates to live and work in impoverished areas, had a fundamental influence of the development of the welfare state. This occurred through their alumni going on to enter the Civil Service and politics, and through the settlements’ ability to powerfully convey the practical experience of voluntary work in the East End to policy makers. The period 1918 – 1959 marks a significant phase in this relationship, with the economic depression, the Second World War and formative welfare state having a significant impact upon the settlements and the communities around them. This thesis draws together the history of these charities with an exploration of the complex networking relationships between local and national politicians, philanthropists, social researchers and the voluntary sector in the period. This thesis argues that work on the ground, an influential dissemination network and the settlements’ experience of both enabled them to influence the formation of national social policy in the period. -

What Happens After an Indecisive Election Result?

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07163, 9 June 2017 What happens after an By Lucinda Maer indecisive election result? Gail Bartlett Inside: 1. Forming a government after a hung parliament 2. “Caretaker” administrations 3. The meeting of a new Parliament 4. The Queen’s Speech 5. An investiture vote? www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 07163, 9 June 2017 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Forming a government after a hung parliament 5 1.1 What kind of government can form? 5 1.2 Historical precedents 6 1.3 When should an incumbent Prime Minister resign? 7 1.4 How long does government formation take? 9 1.5 Internal party consultation 9 1.6 Role of the House of Commons 10 1.7 Effects of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 10 2. “Caretaker” administrations 12 2.1 What is a “caretaker” administration? 12 2.2 The nature of the restrictions on government action 12 2.3 When do the restrictions end? 13 3. The meeting of a new Parliament 15 3.1 When does a Parliament return? 15 4. The Queen’s Speech 17 4.1 When does the Queen’s Speech take place? 17 4.2 The debate on the Address 17 5. An investiture vote? 19 Cover page image copyright UK Parliament 3 What happens after an indecisive election result? Summary Following the 2017 general election, held on 8 June 2017, the Conservative Party was returned as the largest party, but did not have an overall majority in the House of Commons. -

Pakistanis, Irish, and the Shaping of Multiethnic West Yorkshire, 1845-1985

“Black” Strangers in the White Rose County: Pakistanis, Irish, and the Shaping of Multiethnic West Yorkshire, 1845-1985 An honors thesis for the Department of History Sarah Merritt Mass Tufts University, 2009 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Section One – The Macrocosm and Microcosm of Immigration 9 Section Two – The Dialogue Between “Race” and “Class” 28 Section Three – The Realization of Social and Cultural Difference 47 Section Four – “Multicultural Britain” in Action 69 Conclusion 90 Bibliography 99 ii Introduction Jess Bhamra – the protagonist in the 2002 film Bend It Like Beckham about a Hounslow- born, football-playing Punjabi Sikh girl – is ejected from an important match after shoving an opposing player on the pitch. When her coach, Joe, berates her for this action, Jess retorts with, “She called me a Paki, but I guess you wouldn’t understand what that feels like, would you?” After letting the weight of Jess’s frustration and anger sink in, Joe responds, “Jess, I’m Irish. Of course I understand what that feels like.” This exchange highlights the shared experiences of immigrants from Ireland and those from the Subcontinent in contemporary Britain. Bend It Like Beckham is not the only film to join explicitly these two ethnic groups in the British popular imagination. Two years later, Ken Loach’s Ae Fond Kiss confronted the harsh realities of the possibility of marriage between a man of Pakistani heritage and an Irish woman, using the importance of religion in both cases as a hindrance to their relationship. Ae Fond Kiss recognizes the centrality of Catholicism and Islam to both of these ethnic groups, and in turn how religion defined their identity in the eyes of the British community as a whole. -

The Attlee Governments

Vic07 10/15/03 2:11 PM Page 159 Chapter 7 The Attlee governments The election of a majority Labour government in 1945 generated great excitement on the left. Hugh Dalton described how ‘That first sensa- tion, tingling and triumphant, was of a new society to be built. There was exhilaration among us, joy and hope, determination and confi- dence. We felt exalted, dedication, walking on air, walking with destiny.’1 Dalton followed this by aiding Herbert Morrison in an attempt to replace Attlee as leader of the PLP.2 This was foiled by the bulky protection of Bevin, outraged at their plotting and disloyalty. Bevin apparently hated Morrison, and thought of him as ‘a scheming little bastard’.3 Certainly he thought Morrison’s conduct in the past had been ‘devious and unreliable’.4 It was to be particularly irksome for Bevin that it was Morrison who eventually replaced him as Foreign Secretary in 1951. The Attlee government not only generated great excitement on the left at the time, but since has also attracted more attention from academics than any other period of Labour history. Foreign policy is a case in point. The foreign policy of the Attlee government is attractive to study because it spans so many politically and historically significant issues. To start with, this period was unique in that it was the first time that there was a majority Labour government in British political history, with a clear mandate and programme of reform. Whereas the two minority Labour governments of the inter-war period had had to rely on support from the Liberals to pass legislation, this time Labour had power as well as office. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

New Labour, Old Morality

New Labour, Old Morality. In The IdeasThat Shaped Post-War Britain (1996), David Marquand suggests that a useful way of mapping the „ebbs and flows in the struggle for moral and intellectual hegemony in post-war Britain‟ is to see them as a dialectic not between Left and Right, nor between individualism and collectivism, but between hedonism and moralism which cuts across party boundaries. As Jeffrey Weeks puts it in his contribution to Blairism and the War of Persuasion (2004): „Whatever its progressive pretensions, the Labour Party has rarely been in the vanguard of sexual reform throughout its hundred-year history. Since its formation at the beginning of the twentieth century the Labour Party has always been an uneasy amalgam of the progressive intelligentsia and a largely morally conservative working class, especially as represented through the trade union movement‟ (68-9). In The Future of Socialism (1956) Anthony Crosland wrote that: 'in the blood of the socialist there should always run a trace of the anarchist and the libertarian, and not to much of the prig or the prude‟. And in 1959 Roy Jenkins, in his book The Labour Case, argued that 'there is a need for the state to do less to restrict personal freedom'. And indeed when Jenkins became Home Secretary in 1965 he put in a train a series of reforms which damned him in they eyes of Labour and Tory traditionalists as one of the chief architects of the 'permissive society': the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, reform of the abortion and obscenity laws, the abolition of theatre censorship, making it slightly easier to get divorced. -

Nutt Dismissal in Britain Highlights Diverging Drug Views

NEWS Testy debate: Looking ahead: 2009 in review: Biomarkers for Warwick Anderson We take a look prostate cancer discusses funding back at the past stir controversy in Australia year’s headlines 1339 1346 1348 Nutt dismissal in Britain highlights diverging drug views At a time when the US government has Jacqui Smith over a paper Nutt published in signaled a softer stance on medical marijuana, January on perceptions of risk that compared the dismissal of an independent drug advisor 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in Britain has highlighted the UK’s hard-line (MDMA, or ‘ecstasy’) use to horse riding (J. stance on illegal substances. Psychopharmacol. 23, 3–5; 2009). David Nutt, until recently chair of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Public dispute (ACMD), was fired by UK Home Secretary In a statement, Johnson claimed that Nutt’s Alan Johnson on 30 October. The sacking comments “damage efforts to give the public followed the issuing of a press release relating clear messages about the dangers of drugs.” to a lecture on drug risk and classification that Nutt, however, has hit back in a series of Nutt gave in July at King’s College London. interviews attacking the Labour government’s In his lecture, Nutt criticized the lack of approach to the issue of drugs. evidence for the current classification of drugs As Nature Medicine went to press, no less in the UK and claimed that this undermined than five members of the ACMD had resigned the credibility of the official message on drugs. in protest of Nutt’s dismissal. -

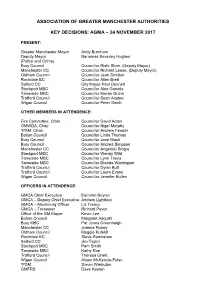

AGMA Decisions Agreed 24 November 2017 FINAL, Item 3F PDF

ASSOCIATION OF GREATER MANCHESTER AUTHORITIES KEY DECISIONS: AGMA – 24 NOVEMBER 2017 PRESENT: Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham Deputy Mayor Baroness Beverley Hughes (Police and Crime) Bury Council Councillor Rishi Shori, (Deputy Mayor) Manchester CC Councillor Richard Leese, (Deputy Mayor) Oldham Council Councillor Jean Stretton Rochdale BC Councillor Allen Brett Salford CC City Mayor Paul Dennett Stockport MBC Councillor Alex Ganotis Tameside MBC Councillor Kieran Quinn Trafford Council Councillor Sean Anstee Wigan Council Councillor Peter Smith OTHER MEMBERS IN ATTENDENCE: Fire Committee, Chair Councillor David Acton GMWDA, Chair Councillor Nigel Murphy TfGM, Chair, Councillor Andrew Fender Bolton Council Councillor Linda Thomas Bury Council Councillor Jane Black Bury Council Councillor Andrea Simpson Manchester CC Councillor Angelicki Stogia Stockport MBC Councillor Wendy Wild Tameside MBC Councillor Lynn Travis Tameside MBC Councillor Brenda Warrington Trafford Council Councillor Dylan Butt Trafford Council Councillor Laura Evans Wigan Council Councillor Jennifer Bullen OFFICERS IN ATTENDENCE: GMCA Chief Executive Eamonn Boylan GMCA – Deputy Chief Executive Andrew Lightfoot GMCA – Monitoring Officer Liz Treacy GMCA – Treasurer Richard Paver Office of the GM Mayor Kevin Lee Bolton Council Margaret Asquith Bury MBC Pat Jones Greenhalgh Manchester CC Joanne Roney Oldham Council Maggie Kufeldt Rochdale BC Steve Rumbelow Salford CC Jim Taylor Stockport MBC Pam Smith Tameside MBC Kathy Roe Trafford Council Theresa Grant Wigan Council Alison McKenzie-Folan TfGM Simon Warbuton GMFRS Dave Keelan Manchester Growth Co Mark Hughes GMCA Julie Connor GMCA Lindsay Dunn GMCA Simon Nokes GMCA Emma Stonier GMCA Sylvia Welsh APOLOGIES: Bolton Council Councillor Cliff Morris Oldham Council Carolyn Wilkins Rochdale BC Councillor Richard Farnell Tameside MBC Steven Pleasant Wigan Council Donna Hall GMP Ian Hopkins GMHSC Partnership Jon Rouse TfGM Jon Lamonte Agenda Item No. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Women Mps in Westminster Photographs Taken May 21St, June 3Rd, June 4Th, 2008

“The House of Commons Works of Art Collection documents significant moments in Parliamentary history. We are delighted to have added this unique photographic record of women MPs of today, to mark the 90th anniversary of women first being able to take their seats in this House” – Hugo Swire, Chairman, The Speaker's Advisory Committee on Works of Art. “The day the Carlton Club accepted women” – 90 years after women first got the vote aim to ensure that a more enduring image of On May 21st 2008 over half of all women women's participation in the political process Members of Parliament in Westminster survives. gathered party by party to have group photographs taken to mark the anniversary of Each party gave its permission for the 90 years since women first got the vote (in photographs to be taken. For the Labour February 1918 women over 30 were first Party, Barbara Follett MP, the then Deputy granted the vote). Minister for Women and Equality, and Barbara Keeley MP, who was Chair of the Labour Party Women’s Committee and The four new composite Caroline Adams, who works for the photographs taken party by Parliamentary Labour Party helped ensure that all but 12 of the Labour women party aim to ensure that a attended. more enduring image of For the Conservative women's participation in the Party, The Shadow Leader of the House of political process survives Commons and Shadow Minister for Until now the most often used photographic Women, Theresa May image of women MPs had been the so called MP and the Chairman “Blair Babes” picture taken on 7th May 1997 of the Conservative shortly after 101 Labour women were elected Party, Caroline to Westminster as a result of positive action by Spelman MP, enlisted the Labour Party. -

Let's Not Go Back to 70S Primary Education Wikio

This site uses cookies to help deliver services. By using this site, you agree to the use of cookies. Learn more Got it Conor's Commentary A blog about politics, education, Ireland, culture and travel. I am Conor Ryan, Dublin-born former adviser to Tony Blair and David Blunkett on education. Views expressed on this blog are written in a personal capacity. Friday, 20 February 2009 SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE UPDATES Let's not go back to 70s primary education Wikio Despite the Today programme's insistence on the term, "independent" is certainly not an apt Contact me description of today's report from the self-styled 'largest' review of primary education in 40 years. It You can email me here. is another deeply ideological strike against standards and effective teaching of the 3Rs in our primary schools. Many of its contributors oppose the very idea of school 'standards' and have an ideological opposition to external testing. They have been permanent critics of the changes of recent decades. And it is only in that light that the review's conclusions can be understood. Of course, there is no conflict between teaching literacy and numeracy, and the other subjects within the primary curriculum. And the best schools do indeed show how doing them all well provides a good and rounded education. Presenting this as the point of difference is a diversionary Aunt Sally. However, there is a very real conflict between recognising the need to single literacy and numeracy out for extra time over the other subjects as with the dedicated literacy and numeracy lessons, and making them just another aspect of primary schooling that pupils may or may not pick up along the way.