RBWF Burns Chronicle 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SETL for Internet Data Processing

SETL for Internet Data Processing by David Bacon A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Computer Science New York University January, 2000 Jacob T. Schwartz (Dissertation Advisor) c David Bacon, 1999 Permission to reproduce this work in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes is hereby granted, provided that this notice and the reference http://www.cs.nyu.edu/bacon/phd-thesis/ remain prominently attached to the copied text. Excerpts less than one PostScript page long may be quoted without the requirement to include this notice, but must attach a bibliographic citation that mentions the author’s name, the title and year of this disser- tation, and New York University. For my children ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Jack Schwartz, for his support and encour- agement. I am also grateful to Ed Schonberg and Robert Dewar for many interesting and helpful discussions, particularly during my early days at NYU. Terry Boult (of Lehigh University) and Richard Wallace have contributed materially to my later work on SETL through grants from the NSF and from ARPA. Finally, I am indebted to my parents, who gave me the strength and will to bring this labor of love to what I hope will be a propitious beginning. iii Preface Colin Broughton, a colleague in Edmonton, Canada, first made me aware of SETL in 1980, when he saw the heavy use I was making of associative tables in SPITBOL for data processing in a protein X-ray crystallography laboratory. -

Modern Programming Languages CS508 Virtual University of Pakistan

Modern Programming Languages (CS508) VU Modern Programming Languages CS508 Virtual University of Pakistan Leaders in Education Technology 1 © Copyright Virtual University of Pakistan Modern Programming Languages (CS508) VU TABLE of CONTENTS Course Objectives...........................................................................................................................4 Introduction and Historical Background (Lecture 1-8)..............................................................5 Language Evaluation Criterion.....................................................................................................6 Language Evaluation Criterion...................................................................................................15 An Introduction to SNOBOL (Lecture 9-12).............................................................................32 Ada Programming Language: An Introduction (Lecture 13-17).............................................45 LISP Programming Language: An Introduction (Lecture 18-21)...........................................63 PROLOG - Programming in Logic (Lecture 22-26) .................................................................77 Java Programming Language (Lecture 27-30)..........................................................................92 C# Programming Language (Lecture 31-34) ...........................................................................111 PHP – Personal Home Page PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor (Lecture 35-37)........................129 Modern Programming Languages-JavaScript -

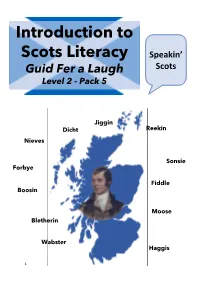

Introduction to Scots Literacy

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution During Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting Packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scot Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scot Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, short bread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

RBWF Burns Chronicle Index

A Directory To the Articles and Features Published in “The Burns Chronicle” 1892 – 2005 Compiled by Bill Dawson A “Merry Dint” Publication 2006 The Burns Chronicle commenced publication in 1892 to fulfill the ambitions of the recently formed Burns Federation for a vehicle for “narrating the Burnsiana events of the year” and to carry important articles on Burns Clubs and the developing Federation, along with contributions from “Burnessian scholars of prominence and recognized ability.” The lasting value of the research featured in the annual publication indicated the need for an index to these, indeed the 1908 edition carried the first listings, and in 1921, Mr. Albert Douglas of Washington, USA, produced an index to volumes 1 to 30 in “the hope that it will be found useful as a key to the treasures of the Chronicle” In 1935 the Federation produced an index to 1892 – 1925 [First Series: 34 Volumes] followed by one for the Second Series 1926 – 1945. I understand that from time to time the continuation of this index has been attempted but nothing has yet made it to general publication. I have long been an avid Chronicle collector, completing my first full set many years ago and using these volumes as my first resort when researching any specific topic or interest in Burns or Burnsiana. I used the early indexes and often felt the need for a continuation of these, or indeed for a complete index in a single volume, thereby starting my labour. I developed this idea into a guide categorized by topic to aid research into particular fields. -

A Lost Collection of Robert Burns Manuscripts: Sir Alfred Law, Davidson Cook, and the Honresfield Collection Patrick G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications English Language and Literatures, Department of 2-6-2015 A Lost Collection of Robert Burns Manuscripts: Sir Alfred Law, Davidson Cook, and the Honresfield Collection Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/engl_facpub Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Publication Info Published in Robert Burns Lives!, ed. Frank R. Shaw, Issue 210, 2015. "A Lost Collection of Robert Burns Manuscripts: Sir Alfred Law, Davidson Cook, and the Honresfield Collection," Robert Burns Lives!, ed. Frank R. Shaw, no. 210 (February 6, 2015): (c) Patrick Scott, 2015. This Article is brought to you by the English Language and Literatures, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “Lost” Collection of Robert Burns Manuscripts: Sir Alfred Law, Davidson Cook, and the Honresfield Collection by Patrick Scott Earlier this month, I was working with Ross Roy’s reminiscences from his twenty-plus years editing The Letters of Robert Burns. Elizabeth Sudduth and I are preparing a selection of Ross’s Burns essays for publication, and the introduction, “Encountering Robert Burns,” brings together sections from the autobiographical oral history interviews that Ross made in the spring of 2012 with shorter passages from other writings, such as his last article for Robert Burns Lives! about his grandfather W. Ormiston Roy. One paragraph about editing the Burns letters brought me up short: The problem is, of course, that over the years letters have disappeared into private hands. -

FROM the MANSE Gary Noonan Easter Sunday Sees the End of Gary’S Placement with Us

Reflections The Magazine of Kay Park Parish Church Issue No 27 April - May 2017 FROM THE MANSE Gary Noonan Easter Sunday sees the end of Gary’s placement with us. In one paragraph of his final report from me, I have written:“ He feels – and patently is – called to the Ministry of Word and Sacrament, and to Parish Ministry. That call must be affirmed in him at the close of every service which he has conducted when the people respond as positively as they have done. He shows a fiery enthusiasm for the old role of Minister but is genuinely open to the new ways which are ahead.” Kay Park, Minister and people, have really enjoyed having him, and also getting to know Ruth, Robbie and Gregor. He goes on to Probation at Alloway Parish Church with the Rev. Neil McNaught. Our thanks, prayers and affection go with him. Farewell St. Paul ends his 2nd letter to the Corinthians Church (v.11) with“ And now, my friends, farewell….” I prefer Eugene Peterson’s version in “The Message”, “And that’s about it, friends”. My retirement on May 7th does not, I hope, mean, “Farewell”; the reason Joan and I are staying in the town (although at the opposite end!) is because of all the friendships we have made here, especially in the congregation: these are not ending. But, as far as being your Minister is concerned, “That’s about it”! What a privilege it has been! I have loved leading worship here; I have felt a deep two- way interaction with the congregation (that doesn’t happen everywhere, believe me!) which has helped me to grow and develop my own faith and proclamation of it. -

![Francis Grose, Ed.] Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3221/francis-grose-ed-classical-dictionary-of-the-vulgar-tongue-853221.webp)

Francis Grose, Ed.] Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue

A landmark in the lexicography of slang in its first edition [Francis Grose, ed.] Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. London: S.[Samuel] Hooper, 1785. 8vo, [208] pages. Francis Grose (ca. 1730–1791) was the son of the Swiss jeweler who created the coronation crown of George II. With assistance from his father, Grose (who developed a precocious interest in antiquities) was appointed to be Richmond Herald in the College of Arms, a post he held from 1755 to 1763. After attaining the rank of captain in the military, Grose set out to research and produce drawings for his first book, The Antiquities of England and Wales (1773–87), which was commercially successful. Grose’s next work, A Guide to Health, Beauty, Riches, and Honour (1783) contained a collection of contemporary quack advertisements with a satirical preface. In the compilation of his Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, Grose, accompanied by his amanuensis and fellow artist Tom Cocking, collected slang terms during late-night visits to London’s roughest neighborhoods and drinking establishments. Grose went on to author A Provincial Glossary (1787) “with a collection of local proverbs and popular superstitions,” Rules for Drawing Caricatures (1788), The Antiquities of Scotland (1789–91), and A Treatise on Ancient Armour and Weapons (1791). While traveling in Scotland making preparations for The Antiquities of Scotland, Grose made the acquaintance of poet Robert Burns and was subsequently immortalized in Burns’ “Verses on Captain Grose” and “On the late Captain Grose’s Peregrinations.” Francis Grose was a corpulent and convivial person who took great pleasure in food and drink; it is fitting that in 1791, soon after traveling to Dublin to start a book on Irish antiquities, he died at the dinner table (reputedly by choking). -

Antiquarian Prints1

Antiquarian Topographical Prints 1550-1850 (As they relate to castle studies) Bibliography Antiquarianism - General Peter N. Miller, (2017). History and Its Objects: antiquarianism and material culture since 1500. NY: Cornell Univ Press. David Gaimster, Bernard Nurse, Julia Steele (eds.), (2007), Making History: Antiquaries in Britain 1707-2007 (London, the Royal Academy of Arts & the Society of Antiquaries, Exhibition Catalogue).* Susan Pearce, (ed) (2007). Visions of Antiquity: The Society of Antiquaries of London 1707–2007. (Society of Antiquaries).* Jan Broadway (2006). "No Historie So Meete": gentry culture and the development of local history in Elizabethan and early Stuart England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. R. Sweet, (2004). Antiquaries: the discovery of the past in eighteenth-century Britain. (London: Hambledon Continuum). Daniel Woolf (2003). The Social Circulation of the Past: English historical culture 1500–1730. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Anthony Griffiths, (1998) The Print in Stuart Britain: 1603-1689,[Exhibition Cat.] British Museum Press.* Philippa Levine, (1986). The Amateur and the Professional: antiquarians, historians and archaeologists in Victorian England, 1838–1886. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). J. Evans, (1956), A history of the Society of Antiquaries, (Oxford University Press for the Society of Antiquaries) D. J. H Clifford (2003), The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford (The History Press Ltd). Topographical Prints and Painting - General Ronald Russell, (2001), Discovering Antique Prints (Shire Books)* Julius Bryant, (1996), Painting the Nation - English Heritage properties as seen by Turner, (English Heritage, London)* Peter Humphries, (1995), On the Trail of Turner in North and South Wales, (Cadw, Cardiff). Andrew Wilton & Anne Lyles (1993), The Great Age of British Watercolours, (Prestel - Exhibition catalogue)* Lindsay Stainton, (1991) Nature into Art: English Landscape Watercolours, (British Museum Press)* Especially Section II ‘Man in the Landscape’ pp. -

Comprehension – Robert Burns – Y5m/Y6d – Brainbox Remembering Burns Robert Burns May Be Gone, but He Will Never Be Forgotten

Robert Burns Who is He? Robert Burns is one of Scotland’s most famous poets and song writers. He is widely regarded as the National Poet of Scotland. He was born in Ayrshire on the 25th January, 1759. Burns was from a large family; he had six other brothers and sisters. He was also known as Rabbie Burns or the Ploughman Poet. Childhood Burns was the son of a tenant farmer. As a child, Burns had to work incredibly long hours on the farm to help out. This meant that he didn’t spend much time at school. Even though his family were poor, his father made sure that Burns had a good education. As a young man, Burns enjoyed reading poetry and listening to music. He also enjoyed listening to his mother sing old Scottish songs to him. He soon discovered that he had a talent for writing and wrote his first song, Handsome Nell, at the age of fifteen. Handsome Nell was a love song, inspired by a farm servant named Nellie Kilpatrick. Becoming Famous In 1786, he planned to emigrate to Jamaica. His plans were changed when a collection of his songs and poems were published. The first edition of his poetry was known as the Kilmarnock edition. They were a huge hit and sold out within a month. Burns suddenly became very popular and famous. That same year, Burns moved to Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. He was made very welcome by the wealthy and powerful people who lived there. He enjoyed going to parties and living the life of a celebrity. -

Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 a Dissertation Submitted in Part

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Sentiment and Laughter: Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Leigh-Michil George 2016 © Copyright by Leigh-Michil George 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Sentiment and Laughter: Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 by Leigh-Michil George Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Jonathan Hamilton Grossman, Co-Chair Professor Felicity A. Nussbaum, Co-Chair This dissertation examines how late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century British novelists—major authors, Laurence Sterne and Jane Austen, and lesser-known writers, Pierce Egan, Charles Jenner, and Alexander Bicknell—challenged Henry Fielding’s mid-eighteenth-century critique of caricature as unrealistic and un-novelistic. In this study, I argue that Sterne, Austen, Egan, and others translated visual tropes of caricature into literary form in order to make their comic writings appear more “realistic.” In doing so, these authors not only bridged the character-caricature divide, but a visual- verbal divide as well. As I demonstrate, the desire to connect caricature with character, and the visual with the verbal, grew out of larger ethical and aesthetic concerns regarding the relationship between laughter, sensibility, and novelistic form. ii This study begins with Fielding’s Joseph Andrews (1742) and its antagonistic stance towards caricature and the laughter it evokes, a laughter that both Fielding and William Hogarth portray as detrimental to the knowledge of character and sensibility. My second chapter looks at how, increasingly, in the late eighteenth century tears and laughter were integrated into the sentimental experience. -

Preconditions/Postconditions Author: Robert Dewar Abstract: Ada Gem

Gem #31: preconditions/postconditions Author: Robert Dewar Abstract: Ada Gem #31 — The notion of preconditions and postconditions is an old one. A precondition is a condition that must be true before a section of code is executed, and a postcondition is a condition that must be true after the section of code is executed. Let’s get started… The notion of preconditions and postconditions is an old one. A precondition is a condition that must be true before a section of code is executed, and a postcondition is a condition that must be true after the section of code is executed. In the context we are talking about here, the section of code will always be a subprogram. Preconditions are conditions that must be guaranteed by the caller before the call, and postconditions are results guaranteed by the subprogram code itself. It is possible, using pragma Assert (as defined in Ada 2005, and as implemented in all versions of GNAT), to approximate run-time checks corresponding to preconditions and postconditions by placing assertion pragmas in the body of the subprogram, but there are several problems with that approach: 1. The assertions are not visible in the spec, and preconditions and postconditions are logically a part of (in fact, an important part of) the spec. 2. Postconditions have to be repeated at every exit point. 3. Postconditions often refer to the original value of a parameter on entry or the result of a function, and there is no easy way to do that in an assertion. The latest versions of GNAT implement two pragmas, Precondition and Postcondition, that deal with all three problems in a convenient way.