MORE REFLECTIONS on CONSEQUENCE* 1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Validities of Pep and Some Characteristic Formulas in Modal Logic

THE VALIDITIES OF PEP AND SOME CHARACTERISTIC FORMULAS IN MODAL LOGIC Hong Zhang, Huacan He School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University,Xi'an, Shaanxi 710032, P.R. China Abstract: In this paper, we discuss the relationships between some characteristic formulas in normal modal logic with their frames. We find that the validities of the modal formulas are conditional even though some of them are intuitively valid. Finally, we prove the validities of two formulas of Position- Exchange-Principle (PEP) proposed by papers 1 to 3 by using of modal logic and Kripke's semantics of possible worlds. Key words: Characteristic Formulas, Validity, PEP, Frame 1. INTRODUCTION Reasoning about knowledge and belief is an important issue in the research of multi-agent systems, and reasoning, which is set up from the main ideas of situational calculus, about other agents' states and actions is one of the most important directions in Al^^'^\ Papers [1-3] put forward an axiom scheme in reasoning about others(RAO) in multi-agent systems, and a rule called Position-Exchange-Principle (PEP), which is shown as following, was abstracted . C{(p^y/)^{C(p->Cy/) (Ce{5f',...,5f-}) When the length of C is at least 2, it reflects the mechanism of an agent reasoning about knowledge of others. For example, if C is replaced with Bf B^/, then it should be B':'B]'{(p^y/)-^iBf'B]'(p^Bf'B]'y/) 872 Hong Zhang, Huacan He The axiom schema plays a useful role as that of modus ponens and axiom K when simplifying proof. Though examples were demonstrated as proofs in papers [1-3], from the perspectives both in semantics and in syntax, the rule is not so compellent. -

The Substitutional Analysis of Logical Consequence

THE SUBSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS OF LOGICAL CONSEQUENCE Volker Halbach∗ dra version ⋅ please don’t quote ónd June óþÕä Consequentia ‘formalis’ vocatur quae in omnibus terminis valet retenta forma consimili. Vel si vis expresse loqui de vi sermonis, consequentia formalis est cui omnis propositio similis in forma quae formaretur esset bona consequentia [...] Iohannes Buridanus, Tractatus de Consequentiis (Hubien ÕÉßä, .ì, p.óóf) Zf«±§Zh± A substitutional account of logical truth and consequence is developed and defended. Roughly, a substitution instance of a sentence is dened to be the result of uniformly substituting nonlogical expressions in the sentence with expressions of the same grammatical category. In particular atomic formulae can be replaced with any formulae containing. e denition of logical truth is then as follows: A sentence is logically true i all its substitution instances are always satised. Logical consequence is dened analogously. e substitutional denition of validity is put forward as a conceptual analysis of logical validity at least for suciently rich rst-order settings. In Kreisel’s squeezing argument the formal notion of substitutional validity naturally slots in to the place of informal intuitive validity. ∗I am grateful to Beau Mount, Albert Visser, and Timothy Williamson for discussions about the themes of this paper. Õ §Z êZo±í At the origin of logic is the observation that arguments sharing certain forms never have true premisses and a false conclusion. Similarly, all sentences of certain forms are always true. Arguments and sentences of this kind are for- mally valid. From the outset logicians have been concerned with the study and systematization of these arguments, sentences and their forms. -

Propositional Logic (PDF)

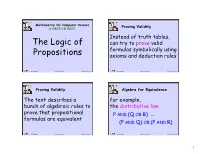

Mathematics for Computer Science Proving Validity 6.042J/18.062J Instead of truth tables, The Logic of can try to prove valid formulas symbolically using Propositions axioms and deduction rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.1 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.2 Proving Validity Algebra for Equivalence The text describes a for example, bunch of algebraic rules to the distributive law prove that propositional P AND (Q OR R) ≡ formulas are equivalent (P AND Q) OR (P AND R) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.3 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.4 1 Algebra for Equivalence Algebra for Equivalence for example, The set of rules for ≡ in DeMorgan’s law the text are complete: ≡ NOT(P AND Q) ≡ if two formulas are , these rules can prove it. NOT(P) OR NOT(Q) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.5 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.6 A Proof System A Proof System Another approach is to Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a start with some valid particularly elegant example of this idea. formulas (axioms) and deduce more valid formulas using proof rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.7 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.8 2 A Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a Axioms: particularly elegant example of 1) (¬P → P) → P this idea. It covers formulas 2) P → (¬P → Q) whose only logical operators are 3) (P → Q) → ((Q → R) → (P → R)) IMPLIES (→) and NOT. The only rule: modus ponens Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.9 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.10 Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Prove formulas by starting with Prove formulas by starting with axioms and repeatedly applying axioms and repeatedly applying the inference rule. -

The Etienne Gilson Series 21

The Etienne Gilson Series 21 Remapping Scholasticism by MARCIA L. COLISH 3 March 2000 Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies This lecture and its publication was made possible through the generous bequest of the late Charles J. Sullivan (1914-1999) Note: the author may be contacted at: Department of History Oberlin College Oberlin OH USA 44074 ISSN 0-708-319X ISBN 0-88844-721-3 © 2000 by Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies 59 Queen’s Park Crescent East Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2C4 Printed in Canada nce upon a time there were two competing story-lines for medieval intellectual history, each writing a major role for scholasticism into its script. Although these story-lines were O created independently and reflected different concerns, they sometimes overlapped and gave each other aid and comfort. Both exerted considerable influence on the way historians of medieval speculative thought conceptualized their subject in the first half of the twentieth cen- tury. Both versions of the map drawn by these two sets of cartographers illustrated what Wallace K. Ferguson later described as “the revolt of the medievalists.”1 One was confined largely to the academy and appealed to a wide variety of medievalists, while the other had a somewhat narrower draw and reflected political and confessional, as well as academic, concerns. The first was the anti-Burckhardtian effort to push Renaissance humanism, understood as combining a knowledge and love of the classics with “the discovery of the world and of man,” back into the Middle Ages. The second was inspired by the neo-Thomist revival launched by Pope Leo XIII, and was inhabited almost exclusively by Roman Catholic scholars. -

Plurals and Mereology

Journal of Philosophical Logic (2021) 50:415–445 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-020-09570-9 Plurals and Mereology Salvatore Florio1 · David Nicolas2 Received: 2 August 2019 / Accepted: 5 August 2020 / Published online: 26 October 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract In linguistics, the dominant approach to the semantics of plurals appeals to mere- ology. However, this approach has received strong criticisms from philosophical logicians who subscribe to an alternative framework based on plural logic. In the first part of the article, we offer a precise characterization of the mereological approach and the semantic background in which the debate can be meaningfully reconstructed. In the second part, we deal with the criticisms and assess their logical, linguistic, and philosophical significance. We identify four main objections and show how each can be addressed. Finally, we compare the strengths and shortcomings of the mereologi- cal approach and plural logic. Our conclusion is that the former remains a viable and well-motivated framework for the analysis of plurals. Keywords Mass nouns · Mereology · Model theory · Natural language semantics · Ontological commitment · Plural logic · Plurals · Russell’s paradox · Truth theory 1 Introduction A prominent tradition in linguistic semantics analyzes plurals by appealing to mere- ology (e.g. Link [40, 41], Landman [32, 34], Gillon [20], Moltmann [50], Krifka [30], Bale and Barner [2], Chierchia [12], Sutton and Filip [76], and Champollion [9]).1 1The historical roots of this tradition include Leonard and Goodman [38], Goodman and Quine [22], Massey [46], and Sharvy [74]. Salvatore Florio [email protected] David Nicolas [email protected] 1 Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom 2 Institut Jean Nicod, Departement´ d’etudes´ cognitives, ENS, EHESS, CNRS, PSL University, Paris, France 416 S. -

A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments

A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments By María Elena Oliveri, René Lawless, and John W. Young A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments María Elena Oliveri, René Lawless, and John W. Young1 1 The authors would like to acknowledge Bob Mislevy, Michael Kane, Kadriye Ercikan, and Maurice Hauck for their valuable input and expertise in reviewing various iterations of the framework as well as Priya Kannan, Don Powers, and James Carlson for their input throughout the technical review process. Copyright © 2015 Educational Testing Service. All Rights Reserved. ETS, the ETS logo, GRADUATE RECORD EXAMINATIONS, GRE, LISTENTING. LEARNING. LEADING, TOEIC, and TOEFL are registered trademarks of Educational Testing Service (ETS). EXADEP and EXAMEN DE ADMISIÓN A ESTUDIOS DE POSGRADO are trademarks of ETS. 1 Abstract In this document, we present a framework that outlines the key considerations relevant to the fair development and use of exported assessments. Exported assessments are developed in one country and are used in countries with a population that differs from the one for which the assessment was developed. Examples of these assessments include the Graduate Record Examinations® (GRE®) and el Examen de Admisión a Estudios de Posgrado™ (EXADEP™), among others. Exported assessments can be used to make inferences about performance in the exporting country or in the receiving country. To illustrate, the GRE can be administered in India and be used to predict success at a graduate school in the United States, or similarly it can be administered in India to predict success in graduate school at a graduate school in India. -

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Papers, 1646-1716

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2779p48t No online items Finding Aid for the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Papers, 1646-1716 Processed by David MacGill; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Gottfried 503 1 Wilhelm Leibniz Papers, 1646-1716 Finding Aid for the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Papers, 1646-1716 Collection number: 503 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Processed by: David MacGill, November 1992 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Online finding aid edited by: Josh Fiala, October 2003 © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Papers, Date (inclusive): 1646-1716 Collection number: 503 Creator: Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm, Freiherr von, 1646-1716 Extent: 6 oversize boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Leibniz (1646-1716) was a philosopher, mathematician, and political advisor. He invented differential and integral calculus. His major writings include New physical hypothesis (1671), Discourse on metaphysics (1686), On the ultimate origin of things (1697), and On nature itself (1698). The collection consists of 35 reels of positive microfilm of more than 100,000 handwritten pages of manuscripts and letters. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Language: English. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections. -

Frege and the Logic of Sense and Reference

FREGE AND THE LOGIC OF SENSE AND REFERENCE Kevin C. Klement Routledge New York & London Published in 2002 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2002 by Kevin C. Klement All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infomration storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klement, Kevin C., 1974– Frege and the logic of sense and reference / by Kevin Klement. p. cm — (Studies in philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-415-93790-6 1. Frege, Gottlob, 1848–1925. 2. Sense (Philosophy) 3. Reference (Philosophy) I. Title II. Studies in philosophy (New York, N. Y.) B3245.F24 K54 2001 12'.68'092—dc21 2001048169 Contents Page Preface ix Abbreviations xiii 1. The Need for a Logical Calculus for the Theory of Sinn and Bedeutung 3 Introduction 3 Frege’s Project: Logicism and the Notion of Begriffsschrift 4 The Theory of Sinn and Bedeutung 8 The Limitations of the Begriffsschrift 14 Filling the Gap 21 2. The Logic of the Grundgesetze 25 Logical Language and the Content of Logic 25 Functionality and Predication 28 Quantifiers and Gothic Letters 32 Roman Letters: An Alternative Notation for Generality 38 Value-Ranges and Extensions of Concepts 42 The Syntactic Rules of the Begriffsschrift 44 The Axiomatization of Frege’s System 49 Responses to the Paradox 56 v vi Contents 3. -

Presupposition Failure and Intended Pronominal Reference: Person Is Not So Different from Gender After All* Isabelle Charnavel Harvard University

Presupposition failure and intended pronominal reference: Person is not so different from gender after all* Isabelle Charnavel Harvard University Abstract This paper aims to show that (one of) the main argument(s) against the presuppositional account of person is not compelling if one makes appropriate assumptions about how the context fixes the assignment. It has been argued that unlike gender features, person features of free pronouns cannot yield presupposition failure (but only falsity) when they are not verified by the referent. The argument is however flawed because the way the referent is assigned is not made clear. If it is assumed to be the individual that the audience can recognize as the referent intended by the speaker, the argument is reversed. Keywords Person, gender, presupposition, assignment, reference, indexicals 1 Introduction Since Cooper (1983), gender features on pronouns are standardly analyzed as presuppositions (Heim and Kratzer 1998, Sauerland 2003, Heim 2008, Percus 2011, i.a.). Cooper’s analysis of gender features has not only been extended to number, but also to person features (Heim and Kratzer 1998, Schlenker 1999, 2003, Sauerland 2008, Heim 2008, i.a.), thus replacing the more traditional indexical analysis of first and second person pronouns (Kaplan 1977 and descendants of it). All pronouns are thereby interpreted as variables, and all phi-features are assigned uniform interpretive functions, that is, they introduce presuppositions that restrict of the value of the variables. However, empirical arguments have recently been provided that cast doubt on the presuppositional nature of person features (Stokke 2010, Sudo 2012, i.a.). In particular, it has been claimed that when the person information is not verified by the referent, the use of a first/second person pronoun does not give rise to a feeling of presupposition failure, as is the case when the gender information does not match the referent’s gender: a person mismatch, unlike a gender mismatch, yields a plain judgment of falsity. -

Bearers of Truth and the Unsaid

1 Bearers of Truth and the Unsaid Stephen Barker (University of Nottingham) Draft (Forthcoming in Making Semantics Pragmatic (ed) K. Turner. (CUP). The standard view about the bearers of truth–the entities that are the ultimate objects of predication of truth or falsity–is that they are propositions or sentences semantically correlated with propositions. Propositions are meant to be the contents of assertions, objects of thought or judgement, and so are ontologically distinct from assertions or acts of thought or judgement. So understood propositions are meant to be things like possible states of affairs or sets of possible worlds–entities that are clearly not acts of judgement. Let us say that a sentence S encodes a proposition «P» when linguistic rules (plus context) correlate «P» with S in a manner that does not depend upon whether S is asserted or appears embedded in a logical compound. The orthodox conception of truth-bearers then can be expressed in two forms: TB1 : The primary truth-bearers are propositions. TB2 : The primary truth-bearers are sentences that encode a proposition «P». I use the term primary truth-bearers , since orthodoxy allows that assertions or judgements, etc, can be truth-bearers, it is just that they are derivatively so; they being truth-apt depends on other things being truth-apt. Some orthodox theorists prefer TB1 –Stalnaker (1972)– some prefer TB2 –Richard (1990). We need not concern ourselves with the reasons for their preferences here. Rather, our concern shall be this: why accept orthodoxy at all in either form: TB1 or TB2 ? There is without doubt a strong general reason to accept the propositional view. -

Handbook of Mereology Total

Simons, P., 1987. Part I is a standard The notion of structure is of central im- reference for extensional mereology. portance to mereology (for the following Parts II and III treat further topics and see also Koslicki 2008, ch. IX). Histori- question some assumptions of extension- cal contributions had this clearly in view; ality. Has an extensive bibliography. for example, as is brought out in Harte 2002, Plato in numerous dialogues grap- ples with the question of how a whole References and further readings which has many parts can nevertheless be a single unified object and ultimately Cartwright, R., 1975, “Scattered Ob- endorses a structure-based response to jects”, as reprinted in his Philosophical this question (see Plato). Wholes, ac- Essays, 1987, Cambridge, MIT Press: cording to Plato’s mature views (as de- 171-86. veloped primarily in the Sophist, Par- Lewis, D., 1991, Parts of Classes, Ox- menides, Philebus and Timaeus), have a ford: Blackwell. dichotomous nature, consisting of both material as well as structural compo- Sanford, D. H., 2003, “Fusion Confu- nents; it is the job of structure to unify sion”, Analysis 63: 1-4. and organize the plurality of material Sanford, D. H., 2011, “Can a sum change parts that are present in a unified whole. its parts?”, Analysis 71: 235-9. A similar conception is taken up and worked out further by Aristotle who Simons, P., 1987, Parts: A Study in On- famously believed that ordinary material tology, Oxford: Clarendon Press. objects, such as houses, are compounds Tarski, A., 1929, “Foundations of the of matter (viz., the bricks, wood, etc.) Geometry of Solids” as reprinted in his and form (viz., the arrangement exhibited Logic, Semantics, Metamathematics, by the material components for the pur- Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959: pose of providing shelter). -

Redalyc.Logical Consequence for Nominalists

THEORIA. Revista de Teoría, Historia y Fundamentos de la Ciencia ISSN: 0495-4548 [email protected] Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea España ROSSBERG, Marcus; COHNITZ, Daniel Logical Consequence for Nominalists THEORIA. Revista de Teoría, Historia y Fundamentos de la Ciencia, vol. 24, núm. 2, 2009, pp. 147- 168 Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea Donostia-San Sebastián, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=339730809003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Logical Consequence for Nominalists Marcus ROSSBERG and Daniel COHNITZ BIBLID [0495-4548 (2009) 24: 65; pp. 147-168] ABSTRACT: It has repeatedly been argued that nominalistic programmes in the philosophy of mathematics fail, since they will at some point or other involve the notion of logical consequence which is unavailable to the nominalist. In this paper we will argue that this is not the case. Using an idea of Nelson Goodman and W.V.Quine's which they developed in Goodman and Quine (1947) and supplementing it with means that should be nominalistically acceptable, we present a way to explicate logical consequence in a nominalistically acceptable way. Keywords: Philosophy of mathematics, nominalism, logical consequence, inferentialism, Nelson Goodman, W.V. Quine. 1. The Argument from Logical Consequence We do not have any strong convictions concerning the question of the existence or non- existence of abstract objects. We do, however, believe that ontological fastidiousness is prima facie a good attitude to adopt.