Production Diary of the Debates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement on the Death of John Chancellor July 13, 1996 Executive

1242 July 13 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1996 should pass the Kassebaum-Kennedy health Statement on the Death of John insurance reform bill which could benefit 25 Chancellor million Americans by saying that you don't July 13, 1996 lose your health insurance when you change jobs or just because someone in your family Hillary and I were saddened to learn of has been sick. In its strongest form, this bill the death of one of the true frontiersmen passed the Senate unanimously. But for of television journalism, John Chancellor. months it slowed to a crawl as Republicans John's scrupulous attention to the facts and insisted on an untested and unlimited pro- his ability to capture the spirit of an issue posal for so-called medical savings accounts won him the hearts and minds of the Amer- that have nothing to do with the fundamental ican people. From his historic coverage of purposes of Kennedy-Kassebaum reforms. a story very personal to me, the desegrega- So I urge them to reject the political games, tion of Central High School in Little Rock, and let's come to a quick agreement. to his renowned political reporting, John We should also reform our illegal immigra- brought us the very best journalism had to tion laws. I support legislation that builds on offer. We extend our sincerest prayers and our efforts to restore the rule of law to our deepest sympathies to his family, his friends, and his colleagues at NBC News. borders, ensures that American jobs are re- served for legal workers, and boosts deporta- tion of criminal aliens. -

Ford Hall Forum Collection (MS113), 1908-2013: a Finding Aid

Ford Hall Forum Collection 1908-2013 (MS113) Finding Aid Moakley Archive and Institute www.suffolk.edu/moakley [email protected] Ford Hall Forum Collection (MS113), 1908-2013: A Finding Aid Descriptive Summary Repository: Moakley Archive and Institute, Suffolk University, Boston MA Collection Number: MS 113 Creator: Ford Hall Forum Title: Ford Hall Forum Collection Date(s): 1908-2013, 1930-2000 Quantity: 85 boxes, 41 cubic ft., 39 lin. ft. Preferred Citation: Ford Hall Forum Collection (MS 113), 1908-2013, Moakley Archive and Institute, Suffolk University, Boston, MA. Abstract: The Ford Hall Forum Collection documents the history of the nation’s longest running free public lecture series. The Forum has hosted some the most notable figures in the arts, science, politics, and the humanities since its founding in 1908. The collection, which spans from 1908 to 2013, includes of 85 boxes of materials related to the Forum's administration, lectures, fund raising, partnerships, and its radio program, the New American Gazette. Administrative Information Acquisition Information: Ownership transferred to Suffolk University in 2014. Use Restrictions: Use of materials may be restricted based on their condition, content or copyright status, or if they contain personal information. Consult Archive staff for more information. Related Collections: See also the Ford Hall Forum Oral History (SOH-041) and Arthur S. Meyers Collection (MS114) held by Suffolk University. Additional collection materials related to the organization --primarily audio and video -

WHCA Video Log

WHCA Video Log Tape # Date Title Format Duration Network C1 9/23/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #1 (Tape 1) In Philadelphia, Domestic Issues BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 ABC C2 9/23/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #1 (Tape 2) In Philadelphia, Domestic Issues BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C3 10/6/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #2 In San Francisco, Foreign Policy BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 ABC C4 10/15/1976 Mondale/Dole Debate BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 NBC C5 10/17/1976 Face the Nation with Walter Mondale BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C6 10/22/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #3 At William & Mary, not complete BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 NBC C7 11/1/1976 Carter Election Special BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C8 11/3/1976 Composite tape of Carter/Mondale activities 11/2-11/3/1976 BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C9 11/4/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ALL C10 11/7/1976 Ski Scene with Walter Mondale BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 WMAL C11 11/7/1976 Agronsky at Large with Mondale & Dole BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 WETA C12 11/29/1976 CBS Special with Cronkite & Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C13 12/3/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ALL C14 12/13/1976 Mike Douglas Show with Lillian and Amy Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 CBS C15 12/14/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ALL C16 12/14/1976 Barbara Walters Special with Peters/Streisand and Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ABC Page 1 of 92 Tape # Date Title Format Duration Network C17 12/16/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C18 12/21/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ALL C19 12/23/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C20 12/29/1976 Good Morning America with Carter and Cabinet Members (Tape 1) BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ABC C21 12/29/1976 Good Morning America with Carter and Cabinet Members (Tape 2) Digital Files, Umatic 60 ABC C22 1/4/1977 Dinah Shore Show with Mrs. -

Cultural Constructions of Democracy and the Public Library in Cold War Wisconsin

Reading versus the Red Bull: Cultural Constructions of Democracy and the Public Library in Cold War Wisconsin Christine Pawley During the run-up to the November 1952 election, newspaper readers in Luxemburg, a small town in Kewaunee County, Wisconsin, encountered com• peting appeals for their vote. The Republican Party dramatized the choices fac• ing the electorate. "Joe McCarthy Says: Give Dee a Good Staff to Control the Red BuU!" proclaimed a typical advertisement. "It's time we all saw Red! Vote Solid Republican November 4th." Depicting a pawing and snorting bull as "Com• munism and Corruption," the ad continued: "In China, Europe and the Middle East, the red bull has enslaved almost three quarter biUion humans In Wash• ington, the headlines tell of corruption and red influence in high places. Contrast all this," it asked "with clean Republican government in Wisconsin. Free of deals and debt. .. free of communism and corruption!"^ The lines of the cold war had formed, as Repubhcans and other critics pointed to the Stalinist domination of Eastern Europe as evidence that although the Demo• crats had won World War II, they had lost the peace.^ Fascism may have gone underground, but already some in politics and the media had found a new bo• gey: communism.^ By the late 1940s, accusations of disloyalty were naultiply- ing; in February 1950, Joseph R. McCarthy, Republican senator from Appleton, Wisconsin (a few miles from Kewaunee County), loaned his name to a phenom• enon that was already under way.** Public rhetoric was infused with the vocabu• lary of patriotism and anti-communism, often presented as synonymous with 0026-3079/2001/4203-087$2.50/0 American Studies, 42:3 (Fall 2001): 87-103 87 88 Christine Pawley democracy. -

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT in AMERICA By. Sean P Mccracken "CBS NEWS Now Projects...NBC NEWS Is Read

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT IN AMERICA By. Sean P McCracken "CBS NEWS now projects...NBC NEWS is ready to declare ...ABC NEWS is now making a call in....CNN now estimates...declares...projects....calls...predicts...retracts..." We hear these few opening words and wait on the edges of our seats as the names and places which follow these familiar predicates make very well be those which tell us in the United States who will occupy the White House for the next four years. We hear the words, follow the talking-heads and read the ever changing scripts which scroll, flash or blink across our television screens. It is a ritual that has been repeated an-masse every four years since 1952...and for a select few, 1948. Since its earliest days, television has had a love affair with politics, albeit sometimes a strained one. From the first primitive experiments at the Republican National Convention in 1940, to the multi angled, figure laden, information over-loaded spectacles of today, the "happening" that unfolds every four years on the second Tuesday in November, known as "Election Night" still holds a special place in either our heart...or guts. Somehow, it still manages to keep us glued to our television for hours on end. This one night that rolls around every four years has "grown up" with many of us over the last 64 years. Staring off as little more than chalk boards, name plates and radio announcers plopped in front of large, monochromatic cameras that barely sent signals beyond the limits of New York City and gradually morphing into color-laden, graphic-filled, information packed, multi channel marathons that can be seen by virtually...and virtually seen by...almost any human on the planet. -

Bulletin June 28, 1974

Missouri Honor A '\Yards for Distinguished Service in Journalism 197 4 UNNERSITY OF MISSOURI-COLUMBIA BULLETIN JUNE 28, 1974 Journalism Honor Awards Seven Honor Awards for Distinguished Service in Journalism were presented at the 65th annual Journalism Week Banquet, April 5, 1974. Medalists this year were: Sam J. Ervin, Jr. , United States senator from North Carolina. Fred Freed, executive producer, NBC News. The award was made posthumously and accepted by John Chancellor, NBC Nightly News anchorman. The National Observer, with Editor Henry Gemmill accepting. Raymond B. Nixon, emeritus professor of journalism and in ternational communication, University of Minnesota. Richard L. Strout, senior Washington correspondent, the Christian Science Monitor. The Sunday Times of London, with Associate Editor Henry Brandon accepting. Robert L. Vickery, publisher, the Salem (Mo.) News. As stipulated when the awards were established by the Uni versity of Missouri School of Journalism in 1930, the medals were awarded "to newspapers, or periodicals, or editors or publishers of newspapers and periodicals, or persons engaged in the practice of journalism for distinguished service performed in such lines of journalistic endeavor as shall be selected each year for consid eration." A Journalism School committee each year considers nomina tions that have been received before November 1. Members give special attention to records of excellence over a period of time, rather than particular occasions of achievement. Nominations for the honor awards may be submitted by in terested parties. Names should be sent before November 1 to the Dean of the Faculty, School of Journalism. After consideration by the Honor Awards committee, nominees are voted on by the faculty and approved by the Chancellor, President, and Board of Curators. -

Document Rum

DOCUMENT RUM EA 097 707 CS 201 632 AUTHOR Atkin, Charles K.; Gantt, Walter TITLE Children's Response to Broadcast News: Exposure, Evaluation, and Learning. PUS DATE Aug 74 NOTE 15p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism (57th, San Diego, California, August 18-21, 1974) ETV PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-411.85 PLUS POSTAGE DLSCRIPTORS *Childhood Attitudes; *Communication (Thought Transfer) ; Elementary School Students; Evaluation; Journalism; Learning; Mass Media; *News Reporting; *Television Research; *Television Viewing ABSTRACT This study provides evidence of the basic parameters of elementary school students' viewing of national, local, and children's news programing. About half of the children studied regularly watched the special Saturday morning newscasts, whie almost half watched adult news programing at least occasionally. News viewing increased steadily from kindergarten through fifth grade. A small number of children expressed positive evaluation of the Saturday "In the News" segmeiits and a much smaller group strongly preferred adult news. Communication about news events with parents and friends is somewhat related to viewing; however, there is little evidence of parent-child similarities in actual exposure behavior. Demographically, sex is the major determinant of news viewing, as boys watched considerably more news programs than did girls. Assuming that exposure is either a sole or a reciprocal causal agent, the following tentative conclusions can be suggested; television news exposure produces moderately increased levels ofknowledge about political affairs and popular events and persons; exposure to television news produces moderately increased levels of interpersonal discussion of news with peers and parents; and it stimulates perhaps half of the children to seek additional information. -

1O1 Most Influential Latinos

Contributors: Kristian Jaime Kimberly Olguin 1O1 MOST INFLUENTIAL LATINOS As usual, these are not all of the leaders, but those in the list are all leaders. Fantastic leaders with a diverse activity, all of them advancing Latinos all over the country and all across industries and professions. All of the leaders included have proven an actual influence on the national scene, not only for the Hispanic community but for the entire country. From lawyers to cabinet members, from media personalities to powerful business figures, this list is a snap shot of the power and influence of Latinos in the US today. Newcomers, like Lin-Manuel Miranda, who has a powerful voice in the entertainment industry, or Agustin Arteaga, the only Latino with the title of Director at one of the most important museums of art in the country, or Andre Arbelaez, who may be the most respected voice for Latinos in the hi-tech industry, make this list a very special one. 1O1 We hope you enjoy reading who they are, where they live, what has been their professional path and even contact them, for these are the leaders forging the future of America. 001 R • Mexican-American 2017 Ruben Salazar Award Alcaraz is best known for his comic La Cucaracha, the first nation- • 1964 in San Diego, CA for Communication at National ally syndicated, politically themed Latino daily comic strip. Launched • Bachelor’s degree in Art and Council of La Raza Annual in 2002, La Cucaracha has become one of the most controversial in Industrial Design from San Conference the history of American comic strips. -

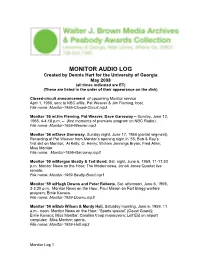

Monitor Audio

MONITOR AUDIO LOG Created by Dennis Hart for the University of Georgia May 2008 (all times indicated are ET) (These are listed in the order of their appearance on the disk) Closed-circuit announcement of upcoming Monitor service April 1, 1955, sent to NBC affils, Pat Weaver & Jim Fleming, host. File name: Monitor-1955-Closed-Circuit.mp3 Monitor ’55 w/Jim Fleming, Pat Weaver, Dave Garroway – Sunday, June 12, 1955, 4-4:18 p.m. -- (first moments of premiere program on NBC Radio). File name: Monitor-1955-Weaver.mp3 Monitor ‘56 w/Dave Garroway, Sunday night, June 17, 1956 (partial segment) Recording of Pat Weaver from Monitor’s opening night in ’55; Bob & Ray’s first skit on Monitor; Al Kelly; O. Henry; William Jennings Bryan; Fred Allen; Miss Monitor. File name: Monitor-1956-Garroway.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Morgan Beatty & Ted Bond, Sat. night, June 6, 1959, 11-11:30 p.m. Monitor News on the Hour; The Modernaires; Jonah Jones Quartet live remote. File name: Monitor-1959-Beatty-Bond.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Hugh Downs and Peter Roberts, Sat. afternoon, June 6, 1959, 3-3:30 p.m. Monitor News on the Hour; Paul Mason on Fort Bragg warfare program; Ernie Kovacs. File name: Monitor-1959-Downs.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Bob Wilson & Monty Hall, Saturday morning, June 6, 1959, 11 a.m.- noon. Monitor News on the Hour; “Sports special” (Coast Guard); Ernie Kovacs; Miss Monitor; Carolina troop maneuvers; Leif Eid on airport computer; Miss Monitor; sports. File name: Monitor-1959-Hall.mp3 Monitor Log 1 Monitor ’61 w/Frank McGee, Sunday night, New Year’s Eve, [December 31, 1961] 7-8 p.m. -

Huntley Finds Life Has Its Drawbacks BOZEMAN, Mont

Huntley Finds Life Has Its Drawbacks BOZEMAN, Mont. July 21. (AP)—Chet Huntley of the Huntley-Brinkley news tele- cast says Life magazine incor- rectly quOted him as saying it "frightens me" that Richard M. Nixon is president. In a letter to the Bozeman Chronicle, Huntley declared Monday that he actually said he "worried about all presi- dents of the United States— whether they will stay healthy, whether• they can stand the strain, their power, the decisions they make, and our tendency to make mon- archs out of them." In New York a Life spokes- man declined immediate com ment, pointing out that nei- CHET HUNTLEY ther Huntley nor his ern-. ... good night, Lite! ployer, NBC, had complained. to the magazine. into the statement that I. think Huntley, 58, retires from Mr. Nixon was shallow," Hunt- the telecast after the Friday ley said. night show and will devote Huntley also denied having full time to developing a Mon- said he had "poured Scotch" tana recreational complex. for President Johnson. The newscaster also dis- owned another quote in the "Well, so it goes," concluded Life interview: "The shallow- Huntley. "The only reasonably ness of the man—President accurate quote was the one Nixon—overwhelms me." about the Eastern Establish- In disclaiming that quote, ment." Huntley said he had ventured In that passage the newscas- the judgment that the 1968 ter was quoted as saying campaign, as waged by all can- "Spiro Agnew is appealing to didates, was shallow and that the most base of elements" the President's rationale for and that the networks had "al- Cambodia was thin. -

Twenty-Fourthannual Celebration

Twenty-FourthAnnual Celebration First AmendmentAwards Dinner Radio Television Digital News Foundation Congratulationsto the 2014 rtdnf first amendment honorees The Associated Press Lester Holt Dave Lougee Robin Sproul Bill Plante NBC News Gannett Broadcasting ABC News CBS News Your Friends at RTDNA and RTDNF Chris Carl David Louie RTDNA Chairman Janice S. Gin Vince Duffy Harvey Nagler RTDNF Chairman Dan Shelley Kathy Walker Amy Tardif Christy Moreno RTDNA Chair-Elect Scott Libin Loren Tobia Terence Shepherd RTDNA Treasurer Brandon Mercer Ed Esposito Carlton Houston RTDNF Treasurer Jam Sardar Randy Bell Mike Cavender RTDNA/F Executive Director Andrew Vrees Bill Roswell Barbara Cochran Mark Kraham RTDNA President Emeritus Terry Scott Kevin Benz Jerry Walsh Immediate Past RTDNF Chairman Sean McGarvy Holly Gauntt 2 First Amendment Awards Dinner | March 12, 2014 Radio Television Digital News Foundation Program WELCOME INTRODUCTION MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mike Cavender Vince Duffy Chris Wallace RTDNA/F Executive Director RTDNF Chair FOX News Awards Presentation FIRST AMENDMENT AWARD The Associated Press Accepted by: Gary Pruitt, President and CEO, The Associated Press Presenter: Tom Curley, Retired, former President & CEO, The Associated Press FIRST AMENDMENT SERVICE AWARD Robin Sproul Vice President and Washington Bureau Chief, ABC News Presenter: Martha Raddatz, Chief Global Affairs Correspondent, ABC News LEONARD ZEIDENBERG FIRST AMENDMENT AWARD Lester Holt Principal Anchor, “Dateline”, Anchor, “NBC Nightly News” Weekend Edition Co-Anchor, -

Download It, and Transcribe It with the to Create a Network of Arab Correspon- Subscribe to Our Print Edition

Vol. 54 No. 4 NIEMAN REPORTS Winter 2000 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 4 The Internet, Technology and Journalism Peering Into the 6 Technology Is Changing Journalism BY TOM REGAN Digital Future 9 The Beginning (and End) of an Internet Beat BY ELIZABETH WEISE 11 Digitization and the News BY NANCY HICKS MAYNARD 13 The Internet, the Law, and the Press BY ADAM LIPTAK 15 Meeting at the Internet’s Town Square EXCERPTS FROM A SPEECH BY DAN RATHER 17 Why the Internet Is (Mostly) Good for News BY LEE RAINIE 19 Taming Online News for Wall Street BY ARTHUR E. ROWSE 21 While TV Blundered on Election Night, the Internet Gained Users BY HUGH CARTER DONAHUE, STEVEN SCHNEIDER, AND KIRSTEN FOOT 23 Preserving the Old While Adapting to What’s New BY KENNY IRBY 25 Wanted: a 21st Century Journalist BY PATTI BRECKENRIDGE 28 Is Including E-Mail Addresses in Reporters’ Bylines a Good Idea? BY MARK SEIBEL 29 Responding to E-Mail Is an Unrealistic Expectation BY BETTY BAYÉ 30 Interactivity—Via E-Mail—Is Just What Journalism Needs BY TOM REGAN 30 E-Mail Deluge EXCERPT FROM AN ARTICLE BY D.C. DENISON Financing News in 31 On the Web, It’s Survival of the Biggest BY MARK SAUTER The Internet Era 33 Merging Media to Create an Interactive Market EXCERPT FROM A SPEECH BY JACK FULLER 35 Web Journalism Crosses Many Traditional Lines BY DAVID WEIR 37 Independent Journalism Meets Business Realities on the Web BY DANNY SCHECHTER 41 Economics 101 of Internet News BY JAY SMALL 43 The Web Pulled Viewers Away From the Olympic Games BY GERALD B.