Women in Conflict Resolution and Peace Building In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Resilient Communities in the Face of Climate Change Through Community-Based Approaches in Somalia

BUILDING RESILIENT COMMUNITIES IN THE FACE OF CLIMATE CHANGE THROUGH COMMUNITY-BASED APPROACHES IN SOMALIA Abdullahi Sheikh Abdisalam, 50-years old farmer and the father of 9 children collects watermelon from his farm in Luuq district of Gedo Region, Somalia. Photo: Mohamed Bashir/NRC. Published by Abdikarim Ali, BRCiS NRC Communication and advocacy coordinator Luuq, also known as Luuq Ganaane, is one of the oldest districts of Gedo region of Jubba land state of Somalia. It locates at the bend of Juba River, where the Juba river flows down from north to south in a horseshoe shape. The district borders Ethiopia and Rabdure (Bakool Region) to the North, Wajiid District (Bakool), and Berdaale District (Bay Region) District to the East, Garbaharey District to the South and Beled Hawa and Dolow Districts to the West. The district has an estimated geographical area of 8,258 km2 and an estimated population of about 65,000 people living in the Luuq town, but the total population of the district is estimated at 185,703 people. Luuq has a hot climatic condition with little rainfall. The temperature is always high, and the areas are cyclically tropical by drought and the floods, which adversely affect the farm-based livelihoods. Several consecutive seasons of rain failure have led failed crop harvesting driving many people into food insecurity. Like any other sector, agriculture has adversely been affected by Somalia’s lack of functional and robust government in more than thirty years. Gedo region, in particular, Luuq district was severely affected, which was one of Somalia’s food basket areas. -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity Somalia Region Africa (excl MENA) Agreement name Declaration of National Commitment (Arta Declaration) Date 05/05/2000 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/intrastate conflict ( Somali Civil War (1991 - ) ) Stage Framework/substantive - partial (Multiple issues) Conflict nature Government/territory Peace process 87: Somalia Peace Process Parties The Transnational Government of Somalia Third parties [Note: Several references to the international community] Description Agreement outlines the responsibilities of the Transitional National Assembly, the election of the Chief Justice, the roles of the President and Prime Minister, particularly, the limitations of power of the President. It includes 17-points of binding principles. The Annexes include a ceasefire; a plan of reconstrution and recovery; and the foundations for representation of the Somali population in the TNA and the national dialogue. Agreement document SO_000505_Declaration of national commitment.pdf [] Groups Children/youth No specific mention. Disabled persons No specific mention. Elderly/age No specific mention. Migrant workers No specific mention. Racial/ethnic/national Substantive group [Summary] Contains substantive consideration of inter-group representation in the Transitional National Assembly. Page 1, • Representation in the Conference and in the "Transitional National Assembly" shall be on the basis of local constituencies (regional /clan mix) Page 3, TOWARD THIS END WE ... 8. pledge to place national interest above clan self interest, personal greed and ambitions Page 6, ANNEX IV BASE OF REPRESENTATION IN THE ... WHAT TO GUARD AGAINST • It must be stressed that representation based on clan affiliations or the assumed strength or importance of certain clan, including the size of territories presumed or traditional belonging to certain clans, would only succeed in perpetuating or reinforcing the division of the nation. -

From the Bottom

Conflict Early Warning Early Response Unit From the bottom up: Southern Regions - Perspectives through conflict analysis and key political actors’ mapping of Gedo, Middle Juba, Lower Juba, and Lower Shabelle - SEPTEMBER 2013 With support from Conflict Dynamics International Conflict Early Warning Early Response Unit From the bottom up: Southern Regions - Perspectives through conflict analysis and key political actors’ mapping of Gedo, Middle Juba, Lower Juba, and Lower Shabelle Version 2 Re-Released Deceber 2013 with research finished June 2013 With support from Conflict Dynamics International Support to the project was made possible through generous contributions from the Government of Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Government of Switzerland Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the official position of Conflict Dynamics International or of the Governments of Norway or Switzerland. CONTENTS Abbreviations 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 8 Conflict Early Warning Early Response Unit (CEWERU) 8 Objectives 8 Conflict Dynamics International (CDI) 8 From the Country Coordinator 9 I. OVERVIEW 10 Social Conflict 10 Cultural Conflict 10 Political Conflict 10 II. INTRODUCTION 11 Key Findings 11 Opportunities 12 III. GEDO 14 Conflict Map: Gedo 14 Clan Chart: Gedo 15 Introduction: Gedo 16 Key Findings: Gedo 16 History of Conflict: Gedo 16 Cross-Border Clan Conflicts 18 Key Political Actors: Gedo 19 Political Actor Mapping: Gedo 20 Clan Analysis: Gedo 21 Capacity of Current Government Administration: Gedo 21 Conflict Mapping and Analysis: Gedo 23 Conflict Profile: Gedo 23 Conflict Timeline: Gedo 25 Peace Initiative: Gedo 26 IV. MIDDLE JUBA 27 Conflict Map: Middle Juba 27 Clan Chart: Middle Juba 28 Introduction: Middle Juba 29 Key Findings: Middle Juba 29 History of Conflict : Middle Juba 29 Key Political Actors: Middle Juba 29 Political Actor Mapping: Middle Juba 30 Capacity of Current Government Administration: Middle Juba 31 Conflict Mapping and Analysis: Middle Juba 31 Conflict Profile: Middle Juba 31 V. -

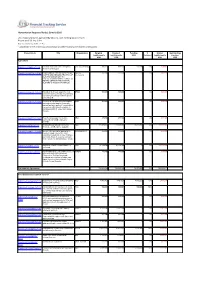

With Funding Status of Each Report As

Humanitarian Response Plan(s): Somalia 2016 List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 23-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R3) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD Agriculture SOM-16/A/84942/5110 Puntland and Lower Juba Emergency VSF (Switzerland) 998,222 998,222 588,380 59% 409,842 0 Animal Health Support SOM-16/A/86501/15092 PROVISION OF FISHING INPUTS FOR SAFUK- 352,409 352,409 0 0% 352,409 0 YOUTHS AND MEN AND TRAINING OF International MEN AND WOMEN ON FISH PRODUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF FISHING GEARS IN THE COASTAL REGIONS OF MUDUG IN SOMALIA. SOM-16/A/86701/14592 Integrated livelihoods support to most BRDO 500,000 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 vulnerable conflict affected 2850 farming and fishing households in Marka district Lower Shabelle. SOM-16/A/86746/14852 Provision of essential livelihood support HOD 500,000 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 and resilience building for Vulnerable pastoral and agro pastoral households in emergency, crisis and stress phase in Kismaayo district of Lower Juba region, Somalia SOM-16/A/86775/17412 Food Security support for destitute NRO 499,900 499,900 0 0% 499,900 0 communities in Middle and Lower Shabelle SOM-16/A/87833/123 Building Household and Community FAO 111,805,090 111,805,090 15,981,708 14% 95,823,382 0 Resilience and Response Capacity SOM-16/A/88141/17597 Access to live-saving for population in SHARDO Relief 494,554 494,554 0 0% 494,554 0 emergency and crises of the most vulnerable households in lower Shabelle and middle Shabelle regions, and build their resilience to withstand future shocks. -

Protection Cluster Update Weekly Report

Protection Cluster Update Funded by: The People of Japan Weeklyhttp://www.shabelle.net/article.php?id=4297 Report 27 th January 2012 European Commission IASC Somalia •Objective Prote ction Monitoring Network (PMN) Humanitarian Aid This update provides information on the protection environment in Somalia, including apparent violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law as reported during the last two weeks through the IASC Somalia Protection Cluster monitoring systems. Incidents mentioned in this report are not exhaustive. They are intended to highlight credible reports to inform and prompt programming and advocacy initiatives by the humanitarian community and national authorities. GENERAL OVERVIEW Clan tensions resumed between Sool, Sanag Clan militias (SSC), including Dhulbahante clan militias and Somaliland forces in Buuhoodle district of Togdheer region after the Somaliland military launched an attack against the SSC militias and captured Buuhoodle town. The fighting resulted in a number of civilian casualties and over 2,000 displacements mainly within Buuhoodle district. Reports suggest that the majority of IDPs returned to their villages when the fighting ended. Following the tensions in Buuhoodle, the Somaliland forces were deployed in parts of Sool region to prevent Dhulbahante clan members from declaring a separate clan administration in the area, which could be perceived by Somaliland authorities as prejudicial to Somaliland’s sovereignty. Following the deployment, members of the Dhulbahante clan demonstrated in favour of creating a separate administration in Laas Canood town, but were faced with a police crackdown. Reports indicate that four civilians were wounded and over 60 people were arrested and detained by the Somaliland security forces. -

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki District 2 Awdal Region Borama District 3 Awdal Region Lughaya District 4 Awdal Region Zeila District 5 Bakool Region El Barde District 6 Bakool Region Hudur District 7 Bakool Region Rabdhure District 8 Bakool Region Tiyeglow District 9 Bakool Region Wajid District 10 Banaadir Region Abdiaziz District 11 Banaadir Region Bondhere District 12 Banaadir Region Daynile District 13 Banaadir Region Dharkenley District 14 Banaadir Region Hamar Jajab District 15 Banaadir Region Hamar Weyne District 16 Banaadir Region Hodan District 17 Banaadir Region Hawle Wadag District 18 Banaadir Region Huriwa District 19 Banaadir Region Karan District 20 Banaadir Region Shibis District 21 Banaadir Region Shangani District 22 Banaadir Region Waberi District 23 Banaadir Region Wadajir District 24 Banaadir Region Wardhigley District 25 Banaadir Region Yaqshid District 26 Bari Region Bayla District 27 Bari Region Bosaso District 28 Bari Region Alula District 29 Bari Region Iskushuban District 30 Bari Region Qandala District 31 Bari Region Ufayn District 32 Bari Region Qardho District 33 Bay Region Baidoa District 34 Bay Region Burhakaba District 35 Bay Region Dinsoor District 36 Bay Region Qasahdhere District 37 Galguduud Region Abudwaq District 38 Galguduud Region Adado District 39 Galguduud Region Dhusa Mareb District 40 Galguduud Region El Buur District 41 Galguduud Region El Dher District 42 Gedo Region Bardera District 43 Gedo Region Beled Hawo District www.downloadexcelfiles.com 44 Gedo Region El Wak District 45 Gedo -

SO 000505 Declaration of National Commitment.Pdf

PA-X, Peace Agreement Access Tool www.peaceagreements.org DECLARATION OF NATIONAL COMMITMENT (Arta Declaration), 5 May 2000 • The Somalia people are desirous oF reaFFirminG the sovereiGn state oF Somalia, and oF ForminG transitional mechanisms (transitional national assembly, transitional Government, an independent judiciary) which shall prepare the country For a peaceFul, permanent and democratic Future. • The Form oF Government shall be parliamentary democracy, with a bicameral national assembly ("Chamber of Elders" to provide leGitimacy, stability and assist in the reconciliation process; and a "Chamber of Representatives"). • The Transitional period shall last 24 months. • The Transitional mechanism shall be based on a "Decentralized" system oF Governance ""reGional autonomy " or Federal structure"), during the transitional period. • The decentralized system oF governance is one that brings diFFerent political communities under a common government For common purposes, and separates regional government For the particular needs of each region • Representation in the ConFerence and in the "Transitional National Assembly" shall be on the basis of local constituencies (regional /clan mix) The National Assembly THE TNA SHALL: • Symbolize power-sharing • be the sole authority with legislative Function during the period in question • elect an interim President (Head of State ) of the country • elect a "government" headed by a Prime Minister. TNA shall approve the Cabinet oF the Prime Minster. The Prime Minster shall be accountable to the TNA -

S 2019 858 E.Pdf

United Nations S/2019/858* Security Council Distr.: General 1 November 2019 Original: English Letter dated 1 November 2019 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia addressed to the President of the Security Council On behalf of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia, and in accordance with paragraph 54 of Security Council resolution 2444 (2018), I have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia. In this connection, the Committee would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Marc Pecsteen de Buytswerve Chair Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia * Reissued for technical reasons on 14 November 2019. 19-16960* (E) 141119 *1916960* S/2019/858 Letter dated 27 September 2019 from the Panel of Experts on Somalia addressed to the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia In accordance with paragraph 54 of Security Council resolution 2444 (2018), we have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia. (Signed) Jay Bahadur Coordinator Panel of Experts on Somalia (Signed) Mohamed Abdelsalam Babiker Humanitarian expert (Signed) Nazanine Moshiri Armed groups expert (Signed) Brian O’Sullivan Armed groups/natural resources expert (Signed) Matthew Rosbottom Finance expert (Signed) Richard Zabot Arms expert 2/161 19-16960 S/2019/858 Summary During the first reporting period of the Panel of Experts on Somalia, the use by Al-Shabaab of improvised explosive devices reached its greatest extent in Somali history, with a year-on-year increase of approximately one third. -

Gedo 120621.Pdf (Английский (English))

Minutes of the Food Security Cluster Meeting Gedo Region ASEP Conference Hall, Dollow, Somalia Thursday, June 21, 2012 _______________________________________________________ Agenda: 1. Introduction 2. Agree on previous minutes 3. Review/follow–up actions from previous meeting 4. Security updates and partner contribution 5. Updates from FEWSNET 6. Presentation of summary district level information by response objective 7. Review of gaps per district and response discussion 8. Any Other Business Introduction The Chair of the meeting guided the members through the agenda and self introduction. He thanked the members present for finding time to attend the meeting and the Advancement for Small Enterprise Program (ASEP) for hosting the meeting. He called for an interactive meeting. Agree on previous minutes The minutes of the previous meeting were ratified by the members for posting on the FSC webpage and on the OCHA website. Review/follow–up actions from previous meeting The election results for the position of Vice Coordinator for Gedo Region would be announced at a later date. Security updates and partner contribution Participants at the meeting reported vehicle ambushes around Garbaharey district in May and June. There were also difficulties in movement and access to certain villages situated between Luuq and other parts of the region during this same period. In June, 2012, in Belet-Hawa town, cases of hit and run leading to fatalities were reported. Nonetheless, Belet–Hawa district remained accessible to local NGOs throughout the previous month with El Waq remaining relatively safe and calm. Abridged Updates from FEWSNET Apart from using satellite imagery, FEWSNET complements information gathered by field enumerators, local partners trained in data collection, Key Informants (KI) and ground truth. -

Nutrition Update January 2007 FSAU FSAU NUTRITION Food Security Analysis Unit - Somalia UPDATE January 2007

FSAU Monthly Nutrition Update January 2007 FSAU FSAU NUTRITION Food Security Analysis Unit - Somalia UPDATE January 2007 Post Deyr ’06/07 Jan to June ’07 Integrated Phase Classification: Post Deyr ’06/07 Nutrition Situation January 2007 1 The FSAU with partners has completed the analysis of the Post Post Deyr ’06/07 Jan to June ’07 Integrated Phase Deyr ’06/07 rains assessment and produced an updated Integrated Classifi cation 1 Phase Classification (IPC) based on the findings (see Map 3). Southern Zone (Juba & Gedo) Nutrition Analysis 2 Overall an improvement in the food security and nutrition indicators Southwest Zone (Bay & Bakool) Nutrition Analysis 4 has been reported in rain fed crop and pastoral production areas. Central and Southeast Zones Nutrition Analysis 5 This improvement is largely due to the second season of good Northeast Zone Nutrition Analysis 7 rains which has had a very positive impact on both animal and Northwest Zone Nutrition Analysis 7 rainfed agricultural production. However, riverine areas in Gedo, Juba valley and Hiran have seen a worsening of the situation due to the compound impacts of flooding and previously poor harvests, Post Deyr ’06/07 Nutrition Situation - including destruction of livelihood assets, displacement, loss of Overview agricultural opportunities, exposure to water borne diseases and destruction of crops. Nevertheless there will be opportunities for Current Nutrition Situation: A summary of the integrated analysis of the flood recession off-season cropping. (see Map 4 Livelihood Zones nutrition situation across the country indicates significant improvement for locations of livelihoods) A more detailed analysis is provided in in the northeast and northwest zones over the last three rainy seasons, the latest FSAU Food Security and Nutrition Post Deyr Brief ’06/07 . -

Belet Hawa District Gedo Region, Somalia

BELET HAWA DISTRICT GEDO REGION, SOMALIA NUTRITION SURVEY October 2002 FSAU/GHC/CARE Belet Hawa Nutrition Survey. October 2002. FSAU and Partners. Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 8 1 INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 SURVEY JUSTIFICATION 9 1.2 1.2 SURVEY OBJECTIVES 10 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION 10 2.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND 10 2.2 FOOD SECURITY OVERVIEW 10 2.3 HISTORICAL FOOD SECURITY AND NUTRITION SITUATION 12 2.4 HUMANITARIAN OPERATIONS IN BELET HAWA DISTRICT 13 2.4.1 DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES 13 2.4.2 HEALTH 13 2.4.3 MORBIDITY SURVEILLANCE 13 2.4.4 GENERAL FOOD AID 14 2.4.5 SELECTIVE FEEDING 14 2.5 WATER AND ENVIRONMENTAL SANITATION 15 2.6 PREVIOUS NUTRITION SURVEYS IN NORTH GEDO 16 3 METHODOLOGY 17 3.1 SURVEY DESIGN 17 3.2 THE SAMPLING PROCEDURE 17 3.2.1 STUDY POPULATION AND SAMPLING CRITERIA 17 3.3 DATA COLLECTION 17 3.3.1 ANTHROPOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS 17 3.3.2 CHILD AGE DETERMINATION 18 3.3.3 OEDEMA 18 3.3.4 MORBIDITY 18 3.3.5 MORTALITY 19 3.4 DESCRIPTION OF SURVEY ACTIVITIES 19 3.5 QUALITY CONTROL PROCEDURES 19 - 2 - Belet Hawa Nutrition Survey. October 2002. FSAU and Partners. 3.6 DATA ANALYSIS 20 3.6.1 ENTRY, CLEANING, PROCESSING AND ANALYSIS 20 3.6.2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDY POPULATION 20 3.6.3 CREATION OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS INDICES 20 4 SURVEY RESULTS 21 4.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY POPULATION 21 4.2 FOOD SOURCES, INCOME SOURCES AND COPING STRATEGIES 22 4.3 WATER AND SANITATION 22 4.4 HEALTH SERVICES 23 4.4.1 NUTRITIONAL STATUS 23 4.4.2 HEALTH, FEEDING PRACTICES AND IMMUNISATION COVERAGE 26 4.4.3 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MALNUTRITION AND OTHER FACTORS 27 4.5 MORTALITY DATA 27 4.6 QUALITATIVE INFORMATION 28 5 DISCUSSION 29 5.1 FOOD SOURCES, INCOME AND COPING MECHANISMS 29 5.1.1 PERSISTENT CHRONIC MALNUTRITION IN BELET HAWA ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. -

Garbaharey District Baseline Assessment and Conflict & Clan

Garbaharey District Baseline Assessment and Conflict & Clan mapping (Activity 1.1) 1 Cover Letter January 16, 2018 To: The Ministry of Interior, Jubbaland State, Somalia District Baseline Assessment and Conflict & Clan mapping report for Garbaharey District Dear MOI Team, DANSOM Research and Consultancy team travelled to Garbaharey for 6 days (December 15th – 21st, 2017) to conduct a thorough District Baseline Assessment and Conflict & Clan mapping for Garbaharey District. Please find attached hereto our assessment report. We thank you in advance for your kind consideration and remain available to directly discuss any questions. Sincerely yours, M. M. Dirir Managing Director +252 (0) 615570144 (Somalia) +254 (0) 722853540 (Kenya) [email protected] www.dansomconsultancy.org 2 Content ACKNOWLEDGMENT ........................................................................................................................ 4 ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................................... 5 a) Maps: ............................................................................................................................... 6 b) Tables: ............................................................................................................................. 6 1. INTRODUCTION: ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Profile and Description of Garbaharey Town .....................................................................