Comparative Breeding Biology of Guillemots Uria Spp. and Razorbills Alca Torda at a Colony in the Northwest Atlantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorbill: Species Information for Marine Special Protection Area Consultations

Natural England Technical Information Note TIN124 Razorbill: species information for marine Special Protection Area consultations The UK government has committed to identifying a network of Special Protection Areas (SPAs) in the marine environment by 2015. Natural England is responsible for recommending potential SPAs in English waters to Defra for classification. This and other related information notes have been written to provide further information to coastal and marine stakeholders about the bird species we are seeking to protect through Marine SPAs. For more information about the process for establishing marine SPAs see TIN120 Establishing Marine Special Protection Areas. Background The Birds Directive (EC Directive on the conservation of wild birds (79/409/EEC)) requires member states to identify SPAs for: rare or vulnerable bird species (as listed in Annex I of the Directive); and regularly occurring migratory bird species. Razorbills Alca torda are a regularly occurring migratory bird species in Europe. They are 37– 39 cm long with a wingspan of 63-68 cm1. Their typical lifespan is 13 years and the oldest Razorbill by Andy Brown reported individual was over 41 years old2. The majority of UK birds nest in the north and west of Scotland. In England, razorbills breed on Conservation Status coasts and islands in the north and south-west. UK amber-listed bird of conservation concern3. The largest English colony is at Flamborough Distribution and population Head and Bempton Cliffs in Yorkshire. Razorbills only breed along North Atlantic coasts, including the UK. Migration/movements Adults and dependent young disperse offshore The Seabird 2000 census lists the UK breeding from colonies in July – August, with adults population at 187,100 individuals, 20% of global becoming flightless during this period due to 4 population with 11,144 individuals breeding in moult. -

Breeding Ecology and Extinction of the Great Auk (Pinguinus Impennis): Anecdotal Evidence and Conjectures

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 101 JANUARY1984 No. 1 BREEDING ECOLOGY AND EXTINCTION OF THE GREAT AUK (PINGUINUS IMPENNIS): ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE AND CONJECTURES SVEN-AXEL BENGTSON Museumof Zoology,University of Lund,Helgonavi•en 3, S-223 62 Lund,Sweden The Garefowl, or Great Auk (Pinguinusimpen- Thus, the sad history of this grand, flightless nis)(Frontispiece), met its final fate in 1844 (or auk has received considerable attention and has shortly thereafter), before anyone versed in often been told. Still, the final episodeof the natural history had endeavoured to study the epilogue deservesto be repeated.Probably al- living bird in the field. In fact, no naturalist ready before the beginning of the 19th centu- ever reported having met with a Great Auk in ry, the GreatAuk wasgone on the westernside its natural environment, although specimens of the Atlantic, and in Europe it was on the were occasionallykept in captivity for short verge of extinction. The last few pairs were periods of time. For instance, the Danish nat- known to breed on some isolated skerries and uralist Ole Worm (Worm 1655) obtained a live rocks off the southwesternpeninsula of Ice- bird from the Faroe Islands and observed it for land. One day between 2 and 5 June 1844, a several months, and Fleming (1824) had the party of Icelanderslanded on Eldey, a stackof opportunity to study a Great Auk that had been volcanic tuff with precipitouscliffs and a flat caught on the island of St. Kilda, Outer Heb- top, now harbouring one of the largestsgan- rides, in 1821. nettles in the world. -

Norway Pout, Sandeel and North Sea Sprat

FINAL REPORT Initial assessment of the Norway sandeel, pout and North Sea sprat fishery Norges Fiskarlag Report No.: 2017-008, Rev 3 Date: January 2nd 2018 Certificate code: 251453-2017-AQ-NOR-ASI Report type: Final Report DNV GL – Business Assurance Report title: Initial assessment of the Norway sandeel, pout and North Sea sprat fishery DNV GL Business Assurance Customer: Norges Fiskarlag, Pirsenteret, Norway AS 7462 TRONDHEIM Veritasveien 1 Contact person: Tor Bjørklund Larsen 1322 HØVIK, Norway Date of issue: January 2nd 2018 Tel: +47 67 57 99 00 Project No.: PRJC -557210 -2016 -MSC -NOR http://www.dnvgl.com Organisation unit: ZNONO418 Report No.: 2017-008, Rev 3 Certificate No.: 251453-2017-AQ-NOR-ASI Objective: Assessment of the Norway sandeel, pout and North Sea sprat fishery against MSC Fisheries Standards v2.0. Prepared by: Verified by: Lucia Revenga Sigrun Bekkevold Team Leader and P2 Expert Principle Consultant Hans Lassen P1 Expert Geir Hønneland P3 Expert Stefan Midteide Project Manager Copyright © DNV GL 2014. All rights reserved. This publication or parts thereof may not be copied, reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, whether digitally or otherwise without the prior written consent of DNV GL. DNV GL and the Horizon Graphic are trademarks of DNV GL AS. The content of this publication shall be kept confidential by the customer, unless otherwise agreed in writing. Reference to part of this publication which may lead to misinterpretation is prohibited. DNV GL Distribution: ☒ Unrestricted distribution (internal and external) ☐ Unrestricted distribution within DNV GL ☐ Limited distribution within DNV GL after 3 years ☐ No distribution (confidential) ☐ Secret Rev. -

Uria Aalge ) Eggshells in Atlantic Canada

08_13025_Bond_NOTE_FINAL_CFN 128(1) 2017-09-01 4:01 AM Page 72 Notes Thickness of Common Murre ( Uria aalge ) Eggshells in Atlantic Canada DonAlD W. P iriE -H Ay and AlExAnDEr l. B onD 1 Department of Biology, University of Saskatchewan, and Environment Canada, 11 innovation Boulevard, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7n 3H5 Canada 1Corresponding author: [email protected] Pirie-Hay, Donald W., and Alexander l. Bond. 2014. T hickness of Common Murre ( Uria aalge ) eggshells in Atlantic Cana - da. Canadian Field-naturalist 128(1): 7 2–76. reported values for eggshell thickness in Common Murre ( Uria aalge ) are few, and even fewer since the decline in use of organochlorine pesticides and other environmental pollutants that caused significant thinning of shells. The eggshells of Common Murres and Thick-billed Murres ( Uria lomvia ) are among the thickest and heaviest, proportionately, of any bird and this represents a non-trivial maternal investment. We measured the length and breadth of Common Murre eggs collected from Machias Seal island, new Brunswick, in 2006, and Gull island, newfoundland and labrador, in 2012, and we measured the thickness of the eggshells. Shell thickness was not related to egg size or volume, and it varied in individual eggs. The shells of Common Murre eggs from Machias Seal island (mean and standard deviation [SD] (0.767, SD 0.078 mm) and Gull island (0.753, SD 0.057 mm ) were significantly thicker than any previously reported value and among the thickest of all birds . Such thickness is likely a result of nesting on rock substrate with no nesting material and, perhaps, high breeding densities. -

A Review of the Fossil Seabirds from the Tertiary of the North Pacific

Paleobiology,18(4), 1992, pp. 401-424 A review of the fossil seabirds fromthe Tertiaryof the North Pacific: plate tectonics,paleoceanography, and faunal change Kenneth I. Warheit Abstract.-Ecologists attempt to explain species diversitywithin Recent seabird communities in termsof Recent oceanographic and ecological phenomena. However, many of the principal ocean- ographic processes that are thoughtto structureRecent seabird systemsare functionsof geological processes operating at many temporal and spatial scales. For example, major oceanic currents,such as the North Pacific Gyre, are functionsof the relative positions of continentsand Antarcticgla- ciation,whereas regional air masses,submarine topography, and coastline shape affectlocal processes such as upwelling. I hypothesize that the long-termdevelopment of these abiotic processes has influencedthe relative diversityand communitycomposition of North Pacific seabirds. To explore this hypothesis,I divided the historyof North Pacific seabirds into seven intervalsof time. Using published descriptions,I summarized the tectonicand oceanographic events that occurred during each of these time intervals,and related changes in species diversityto changes in the physical environment.Over the past 95 years,at least 94 species of fossil seabirds have been described from marine deposits of the North Pacific. Most of these species are from Middle Miocene through Pliocene (16.0-1.6 Ma) sediments of southern California, although species from Eocene to Early Miocene (52.0-22.0 Ma) deposits are fromJapan, -

The Amazon River Dolphin

lMATA Dedicated to those who serve marine mammal science through training, public display, research, husbandry, conservation, and education. Back. Cover: Graphics play like a sentinel over Tacoma. an important role in the Washington, site of the 22nd public display of animals; Annual IMATA Conference. they are essential education From COver: Chuckles, the Photograph by Mark Holden. tools that provide the public only Amazon River dolphin with a wide range of in North America, resides at important information about the Pittsburgh Zoo in animals and the environment. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Marcye Photograph by n'm Smith. Miller-Lebert Copyright 1994. AIl of the articles contained within Soundings are the personal views of the respective authors and not necessarily the views of IMATA . DESIGN & PRODUCTION: I-deal Services, San Diego, California (619) 275-1800 Page 2 Spring 1994 ~- --- ---- --- lMATA PUBLlCAnONS COMMlTIEE Editor John Kirtland Regional The Dolphin Expedence Editorial Director Reports Dave Force Designed to help members Sea World Q/Texas keep track of what is going Assodate Editor on in other facilities around :.Jedra Hecker the world. i\arional Aquadum in Baltimore IMATA'S Growth Contributing Editors Jim Clarke and Development Pete Davey Greg Dye IMATA is dedicated to Steve Shippee providing and advancing the Kari Snelgrove The Amazon most professional. effective, Contributing Writers and humane care and Kathy Sdao River Dolphin handling of all marine Jeff Fasick Learning about this species is a animals in all habitats. Editoria) Advisory Board challenge. Few Inia have been Randy Brill, Ph.D. housed in captivity for long NCCOSCINRaD periods making research of the Brian E. -

Razorbill Alca Torda in North Norway

THE EFFECT OF PHYSICAL AND BIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS ON THE BREEDING SUCCESS OF RAZORBILLS (ALCA TORDA L. 1758) ON MACHIAS SEAL ISLAND, NB IN 2000 AND 2001 by Virgil D. Grecian Bachelor of Science (Hon), Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1996 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Graduate Academic Unit of Biology Supervisors: A.W. Diamond, Ph.D., Biology and Forestry & Environmental Management, J.W. Chardine, Ph.D., Canadian Wildlife Service Supervisory Committee: D.J. Hamilton, Ph.D., Mt Allison University Examining Board: This thesis is accepted. ………………………………………… Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada December, 2004 ABSTRACT The influence of various physical and biological parameters on the breeding biology of Razorbills (Alca torda) on Machias Seal Island (MSI) was studied in 2000 and 2001. The major predators (gulls) on seabird eggs and chicks on MSI are controlled, providing an unusual opportunity to study breeding biology in the virtual absence of predation. The timing of egg-laying was right skewed in both years. A complete survey 10-14 June 2000 of all Razorbill breeding habitat on MSI was combined with radio telemetry to estimate the total number of inaccessible breeding sites that may not have been counted. A corrected breeding pair estimate for MSI is 592 ± 17 pairs. Overall breeding success was 55% in 2000 and 59% in 2001. Most chicks that hatched also departed the island, so differences in breeding success were due chiefly to differences in hatching success. Adults breeding in burrows were more successful than adults in crevice and open nest sites. -

International Black-Legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents

ARCTIC COUNCIL Circumpolar Seabird Expert Group July 2020 International Black-legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................4 CAFF Designated Agencies: Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway Chapter 2: Ecology of the kittiwake ....................................................................................................................6 • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada Species information ...............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) Habitat requirements ............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland Life cycle and reproduction ................................................................................................................................................................................7 • Icelandic Institute of Natural -

Alcid Identification in Massachusetts

ALCID IDENTIFICATION IN MASSACHUSETTS by Richard R. Veit, Tuckernuck The alcldae, a northern circvimpolar family of sesbirds, are memhers of the order Charadrilformes and thus most closely related to the gulls, skuas, and shorehirds. All alcids have approximately elliptical bodies and much reduced appendages, adaptations for insulation as well as a streamlined trajectory under water. Their narrow flipperlike wings are modified to reduce drag durlng underwater propulsión, and are, therefore, comparatively inefficient for flight. Razorbills, murres, and puffins feed predominately on fish, such as the sand launce, capelin, Arctic cod, herring, and mackerel. The Dovekie, by far the smallest Atlantic alcid, eats zooplankton exclusively, such as the superabundant "krill." The Black Guillemot, unique.in its con- finement to the shallow littoral zone, feeds largely on rock eels or gunnel. As with many pelagic birds, the alcids' dependence on abundant marine food restricts them to the productive vaters of the high latitudes. Bio- logical productivity of the oceans increases markedly towards the poles, largely because the low surface temperaturas there maintain convection currents which serve to raise large quantities of dissolved mineral nu triente to the siirface. The resultant high concentration of nutriente near the surface of polar seas supports enormous populations of plankton and, ultimately, the fish upon which the largar alcids feed. Alcids are comparatively weak flyers and are not regularly migratory, but rather disperse from their breeding ranga only when forced to do so by freezing waters or food scarcity. Massachusetts lies at the periphery of the ranges of these birds, with the exception of the Razorbill. It i& only under exceptional circumstances, such as southward irruptions coupled with strong northeasterly storms that substantial numbers of alcids are observad along the Massachusetts coastline. -

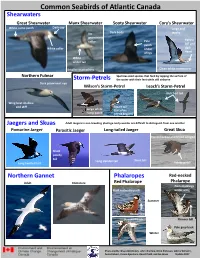

Common Seabirds of Atlantic Canada

Common Seabirds of Atlantic Canada Shearwaters Great Shearwater Manx Shearwater Sooty Shearwater Cory’s Shearwater White rump patch dark Dark cap Large and cap Dark body stocky No dark prominent head Yellow collar Pale patch bill and dark dark White collar under yellowhead belly wings bill White broad under tail wings Smaller than others Clean white underparts Northern Fulmar Sparrow-sized species that feed by tapping the surface of Storm-Petrels the water with their feet while still airborne Dark prominent eye Wilson’s Storm-Petrel Leach’s Storm-Petrel Notched tail Wing beat shallow and stiff Square tail Large white (feet often rump patch extend beyond) Jaegers and Skuas Adult Jaegers in non-breeding plumage and juveniles are difficult to distinguish from one another Pomarine Jaeger Parasitic Jaeger Long-tailed Jaeger Great Skua Hunchbacked and broad winged Short pointy tail Long slender tail Short bill Long twisted tail White patch Northern Gannet Phalaropes Red-necked Adult Immature Red Phalarope Phalarope Dark markings Bold red underparts under wing Summer Thicker bill White chin Streaked back Thinner bill Pale grey back Winter Photo credits: Bruce Mactavish, John Chardine, Brian Patteson, Sabina Wilhelm, Anna Calvert, Carina Gjerdrum, Dave Fifield, and Ian Jones. Update 2017 Common Seabirds of Atlantic Canada Black wing-tipped Gulls Herring Gull Great Black-backed Gull Black-legged Kittiwake Adult Adult Has brownish Breeding adult Winter adult head in winter Dark patch Marbled More uniform behind underwing brown than eye coverts -

Age and Sex of Common Murres Uria Aalge Recovered During the 1997-98 Point Reyes Tarball Incidents in Central California

51 AGE AND SEX OF COMMON MURRES URIA AALGE RECOVERED DURING THE 1997-98 POINT REYES TARBALL INCIDENTS IN CENTRAL CALIFORNIA HANNAHROSE M. NEVINS1 & HARRY R. CARTER 2, 3 1Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, 8272 Moss Landing Road, Moss Landing, CA 95039 USA, e-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA 95521 USA 3Present address: 5700 Arcadia Road, Apt #219, Richmond, B.C. V6X2G9 Canada Received 9 April 2003, accepted 11 October 2003 SUMMARY NEVINS, H. M. & CARTER, H. R. Age and sex of Common Murres Uria aalge recovered during the 1997-98 Point Reyes Tarball Incidents in central California. Marine Ornithology 31: 51-58. We examined 1,138 Common Murre Uria aalge carcasses recovered along the central California coast from November 1997 through March 1998 during the Point Reyes Tarball Incidents, a prolonged oiling event traced to the sunken vessel S. S. Jacob Luckenbach. We used head plumage, supraorbital ridge, and bursa of Fabricius, to classify age among carcasses as hatch-year (HY), or after-hatch year (AHY). We then separated AHY birds into two maturity categories based on gonad development: subadult and adult. The observed age class composition (14.6% HY, 37.6% subadult, and 47.8% adult) was not different from expected values generated with a stage-based matrix model that assumed a year-round resident population. The sex ratio for HY birds was equal (1.2:1), indicating little difference in at-sea distribution among male and female HY birds during winter. We found male-biased sex ratios in subadult (1.6:1) and adult (1.5:1) age classes. -

Uria Lomvia) and Black-Legged Kittiwakes (Rissa Tridactyla

A First Count of Thick-billed Murres ( Uria lomvia ) and Black-legged Kittiwakes ( Rissa tridactyla ) Breeding on Bylot Island ANTHONY J. G ASTON 1, 4 , MARC -A NDRÉ CYR 2, and KIERAN O’D ONOVAN 3 1Science and Technology Branch, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H3 Canada 2Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Place Vincent Massey, 351 St. Joseph Boulevard, Gatineau, Quebec K1A 0H3 Canada 3308a Klukshu Avenue, Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 3Y1 Canada 4Corresponding author: [email protected] Gaston, Anthony J., Marc-André Cyr, and Kieran O’Donovan. 2017. A first count of Thick-billed Murres ( Uria lomvia ) and Black-legged Kittiwakes ( Rissa tridactyla ) breeding on Bylot Island. Canadian Field-Naturalist 131(1): 69 –74. https:// doi.org/10.22621/cfn.v 131i 1.1953 Bylot Island, part of Sirmilik National Park, supports two major breeding colonies of intermingled Thick-billed Murres ( Uria lomvia ) and Black-legged Kittiwakes ( Rissa tridactyla ): at Cape Hay near the northwest tip and at Cape Graham Moore at the opposite end of the island. Although the size of these colonies has been estimated previously, there is no information on how the estimates were made, except for Thick-billed Murres at Cape Hay in 1977, when the numbers were based on sampling only about 30% of the colony. In 2013, high-resolution digital photographs of the whole area of both colonies were taken in July, when most birds were probably incubating eggs. Individual birds were counted on the photographs, and the numbers were corrected for image quality and converted to numbers of breeding pairs based on correction factors from another High Arctic colony.