The Evolving Perception of Desert in American Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 20, 2017 Movie Year STAR 351 P Acu Lan E, Bish Op a B Erd

Movie Year STAR 351 Pacu Lane, Bishop Aberdeen Aberdeen Restaurant, Olancha Airflite Diner, Alabama Hills Ranch Anchor Alpenhof Lodge, Mammoth Lakes Benton Crossing Big Pine Bishop Bishop Reservation Paiute Buttermilk Country Carson & Colorado Railroad Gordo Cerro Chalk Bluffs Inyo Convict Lake Coso Junction Cottonwood Canyon Lake Crowley Crystal Crag Darwin Deep Springs Big Pine College, Devil's Postpile Diaz Lake, Lone Pine Eastern Sierra Fish Springs High Sierras High Sierra Mountains Highway 136 Keeler Highway 395 & Gill Station Rd Hoppy Cabin Horseshoe Meadows Rd Hot Creek Independence Inyo County Inyo National Forest June Lake June Mountain Keeler Station Keeler Kennedy Meadows Lake Crowley Lake Mary 2012 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2013 DOCUMENTARY 2013 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2014 DOCUMENTARY 2014 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2015 DOCUMENTARY 26 Men: Incident at Yuma 1957 Tristram Coffin x 3 Bad Men 1926 George O'Brien x 3 Godfathers 1948 John Wayne x x 5 Races, 5 Continents (SHORT) 2011 Kilian Jornet Abandoned: California Water Supply 2016 Rick McCrank x x Above Suspicion 1943 Joan Crawford x Across the Plains 1939 Jack Randall x Adventures in Wild California 2000 Susan Campbell x Adventures of Captain Marvel 1941 Tom Tyler x Adventures of Champion, The 1955-1956 Champion (the horse) Adventures of Champion, The: Andrew and the Deadly Double1956 Champion the Horse x Adventures of Champion, The: Crossroad Trail 1955 Champion the Horse x Adventures of Hajji Baba, The 1954 John Derek x Adventures of Marco Polo, The 1938 Gary Cooper x Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok 1951-1958 Guy Madison Affairs with Bears (SHORT) 2002 Steve Searles Air Mail 1932 Pat O'Brien x Alias Smith and Jones 1971-1973 Ben Murphy x Alien Planet (TV Movie) 2005 Wayne D. -

Gene Autry Personal Papers and Business Archives T.MSA.28

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8zp46v9 No online items Finding Aid to the Gene Autry Personal Papers and Business Archives T.MSA.28 Finding aid prepared by Holly Rose Larson Autry National Center, Autry Library 4700 Western Heritage Way Los Angeles, CA, 90027 (323) 667-2000 ext. 349 [email protected] 2012 January 27 Finding Aid to the Gene Autry T.MSA.28 1 Personal Papers and Business Archives T.MSA.28 Title: Gene Autry Personal Papers and Business Archives Identifier/Call Number: T.MSA.28 Contributing Institution: Autry National Center, Autry Library Language of Material: English Physical Description: 446.0 Linear feet(approximately 300 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1900-2002 Abstract: Orvon Gene Autry (born September 29, 1907 - died October 2, 1998) was a legendary recording and movie star whose career spanned over 60 years in the entertainment industry. Sometimes called “The Singing Cowboy,” Autry was also a broadcast executive for KTLA and owned the Major League baseball team, the Los Angeles Angels, among other business pursuits. Autry also co-founded the Gene Autry Western Heritage Museum, now known as The Autry National Center of the American West, with wife Jackie Autry and Monte and Joanne Hale in 1988. The Gene Autry Personal Papers and Business Archives span from 1900 to 2002 and document Autry’s personal and family life, including wives Ina Mae Spivey and Jackie Ellam; Autry’s military career during World War II; entertainment career; other business holdings; and honors received. Materials include administrative records; advertising material; awards; ephemera; correspondence; photographic material; posters; scrapbooks; and sheet music. -

Reagan - General” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 39, folder “Reagan - General” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 39 of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library RONALD WILSON REAGAN Ronald Reagan was elected 33rd Governor of California on November 8, 1966. He was re-elected Nov. 3, 1970 for second four-year term. He did not seek re-election to.third term. Gov. Reagan was born Feb. 6, 1911 in Tampico, Ill., to Nellie and John Reagan. He married the former Nancy Davis on March 4,. 1952. The couple has two children, a daughter, Patricia Ann, (22) and a son, Ronald Prescott, (17). They reside in Pacific Palisades (Los Angeles) , Calif. Gov. Reagan also has two other children, Maureen, and Michael. Ronald Reagan was educated in the public schools of Illinois. He was graduated from Eureka College, Eureka, Ill., in 1932 with a degree in economics and sociology. -

The Great Ride of Our Parks

Highline Autos Highline Autos Yellowstone Bus- photo Museum of the Rockies Grand Canyon Railway GreatGarages Crater Lake National Park Lodge Our National Parks at 100: What a Ride! by David M. Brown This year, our National Park Service (NPS) is celebrating The Boats of Crater Lake its Centennial, and what a ride, and rides, it has been for the Approximately 500,000 visitors enjoy Crater Lake millions of visitors who have enjoyed them: on horse, by National Park annually, including driving the 33-mile Rim stagecoach, car, carriage, bus and boat. Drive around the spectacular lake, the deepest in the United President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Park States at 1,943 feet. The deep-blue waters, considered the Service Act on August 25, 1916. At the time, the Department world’s cleanest body of water, fill a caldera scooped out 7,700 of Interior was overseeing 14 national parks, 21 national years ago when volcanic 12,000-foot Mount Mazama col- monuments and Native American reservation sites at Hot lapsed. Similarly, near the southwest shore, Wizard Island is Springs, Arkansas, and the Casa Grande Ruins, Arizona. But, a cinder cone on a platform built after the climactic eruption. disorganization was creating many challenges. Private watercraft have never been permitted on Crater Crater Lake: the deepest in the U.S.- photo Susan Manganiello The Boats of Crater Lake The NPS was, therefore, established, “to conserve the Lake since its now 183,000 acres were placed under federal scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life protection in 1902 as a national park. -

2019 Death Valley Visitor Guide

DDAee Visitors Gaauide To tthh VVaalllleeyy 12th Edition Websites: Armargosa Conservancy, Shoshone, www.armargosaconservancy.org Death Valley Chamber of Commerce, www.deathvalleychamber.org Death Valley National Park, www.nps.gov/deva Shoshone Village, Shoshone, www.shoshonevillage.com Stovepipe Wells Village, www.stovepipewells.com Panamint Springs Resort, www.panamintsprings.com Death Valley Natural History Association, www.dvnha.org Death Valley Conservancy, Table of Contents www.dvconservancy.org Direct Results Media, Inc. Stunning Sights Directand Scene s Results Media, Inc.Page 4 Renovations Create An Oasis Page 6 Business Cards Rodney Preul Tecopa’s Restaurant Renaissance Page 8 Sales Associate Extraordinary Tecopa and Shosho3.5x2ne Page 10 Borax Wagons Find a New Home Page 12 6000 Bel Aire Way Cell: 760-382-1640 Bakersfield, CA 93301 [email protected] 20 Mule Team Canyon Page 14 Dante’s ‘Jaw-Dropping’ View Page 15 The 2019 Death Valley Visitor Guide is produced by the Lone Pine Chamber of Death Valley’s Dark Sky Page 16 Commerce, the Death Valley Chamber of Commerce, and the County of Inyo. The Mysterious Race Track Page 17 The contents do not necessarily reflect Direct Results Media, Inc. Direct Results Media, Inc. the views of the Lone Pine Chamber of Commerce, the Death Valley Chamber Jets Visit Star Wars Canyon Page 18 of Commerce, Death Valley National Park, or the County of Inyo. (Except for Death Valley Hot Fun Facts Page 20 our view that Death Valley is a spectac - Jerry Elford Robert Asianian ular place to visit. We will all definitely Sales Manager own that one.) Published by Direct Re - Attractions At A Glance Sales Associate Page 21 sults Media. -

7Firemen Saved

U- - Distribution Today ' RedBqnk Arm 26,675 , Cop^ght-The Red. B«ak Register, Inc. 1968. DIAL 741-0010 MONMOUTH COlWtY'5 HOJKE NEWSPAPER FOR 88 YEARS FRIDAY, DBCJSMBER 2?, 1966 In Dramatic New York Rescue NE7W YOR KFiremen (AP) — A Times Square area crowd of thou- snapped to attentioSavedn and saluted. Then he shouted above the sands cheered itself hoarse as firemen — risking death In din: "Merry Christmas, fireman," flame and smoke with every step — rescued seven of their The'episode brought a new burst of cheers from hundreds comrades trapped in the rubble of a four-story building that of firemen on the street and the spectators toward the front collapsed on them. of the crowd watching the fire that wrecked an unoccupied One by one, the seven men were dragged out last night and building on 6th Ave. near 45th St. early today from behind blazing wreckage and tons of wood The flames, at their height, flared like torches through the and metal which might weH have been their tomb. burned roof. , AU were taken to Bellevue Hospital. None appeared to be The sftven men were trapped about 10 p.m., and the last was brought to safety at 1:26 a.m. Electric-powered saws -seriously injured but all were held for observation. went used to cut through the debris. The' trapped men were to The sixth man rescued — his face'blackened and Ms' uni- 1 radio communication with firemen outside during part of the form in smoking rags — sat up on a stretcher, grinned, waved rescue operations. -

To Download the 2018 Inyo County

VISITOR’S GUIDE TO IINNYYOOCCOOUUNNTTYY 11 TH EDITION www.TheOtherSideOfCalifornia.com Table of Contents Chamber of Commerce of Inyo County Birds Come Back to Owens Lake Page 4 Bishop Chamber of Commerce & Borax Wagons Find A New Home Page 6 Visitor Center 690 N. Main St. Bishop, CA 93514 Enchanting Fall Colors Page 8 760-873-8405 1-888-395-3952 760-873-6999 Enjoy Bishop’s Big Backyard Page 10 [email protected] www.bishopvisitor.com Appealing Adventures in Lone Pine Page 11 Death Valley Chamber of Commerce 118 Highway 127 Everyone Loves A Parade Page 12 P.O. Box 157 Shoshone, CA 92384 760-852-4524 Historic Independence Page 14 760-852-4144 www.deathvalleychamber.org Direct Results Media, Inc. Direct ResultsLone Media, Pine Inc. Big Pine: An Adventure Hub Page 15 Chamber of Commerce 124 Main St BusinessPO B oCardsx 749 Inyo County Fun Facts Page 16 Lone Pine, CA 93545 Rodney Preul Ph: 760-876-4444 Fx: 760-876-9205 Sales Associate Owens River Links LA And Inyo Page 17 [email protected] https://w3.5x2ww.lonepinechamber.org Inyo Attractions At A Glance Page 19 6000 Bel Aire Way Cell: 760-382-1640 Bakersfield, CA 93301 [email protected] The 2018 Inyo County Visitor Guide is produced by the Lone Pine Chamber of Government Agencies: Commerce and the County of Inyo. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) contents do not necessarily reflect the views 760-872-4881 of the Lone Pine Chamber of Commerce or the County of Inyo. (Except for our view that Inyo County is a spectacular place to visit. -

The Death Valley Visitor's Guide

DDAee Visitors Gaauide To tthh VVaalllleeyy 11th Edition Websites: Armargosa Conservancy, Shoshone, www.armargosaconservancy.org Death Valley Chamber of Commerce, www.deathvalleychamber.org Death Valley National Park, www.nps.gov/deva Shoshone Village, Shoshone, www.shoshonevillage.com Stovepipe Wells Village, www.stovepipewells.com Panamint Springs Resort, www.panamintsprings.com Death Valley Natural History Association, www.dvnha.org Death Valley Conservancy, www.dvconservancy.org Direct Results Media, Inc. Direct Results Media, Inc. Business Cards Rodney Preul Table of Contents Sales Associate Stunning Sights and Scenes Page 4 Extraordinary Tecopa and Shos3.5x2hone Page 6 6000 Bel Aire Way Cell: 760-382-1640 Borax Wagons Find a New Home Page 8 Bakersfield, CA 93301 [email protected] Death Valley Fun Facts Page 10 Tecopa’s Restaurant Renaissance Page 11 The 2018 Death Valley Visitor Guide is produced by the Lone Pine Chamber Death Valley’s Dark Sky Page 15 of Commerce, the Death Valley Chamber of Commerce, and the The Mysterious Race Track Page 16 County of Inyo. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views of the Renovations CDirectreate An O Resultsasis Media, Inc.Page 17 Direct Results Media, Inc. Lone Pine Chamber of Commerce, the Death Valley Chamber of Commerce, Death Valley National 20 Mule Team Canyon Page 18 Park, or the County of Inyo. (Except for our view that Death Valley is a Dante’s ‘Jaw-Dropping’ VieJerryw Elford Page 19 Robert Asianian spectacular place to visit. We will all definitely own that one.) Attractions At A Glance Sales Associate Page 20 Sales Manager Direct Results Media, Inc. Direct Results Media, Inc. -

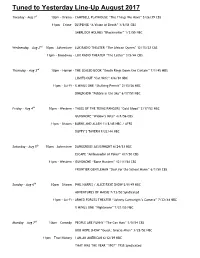

Tuned to Yesterday Line-Up August 2017

Tuned to Yesterday Line-Up August 2017 Tuesday - Aug 1st 10pm – Drama – CAMPBELL PLAYHOUSE “The Things We Have” 5/26/39 CBS 11pm – Crime – SUSPENSE “A Vision of Death” 3/8/51 CBS SHERLOCK HOLMES “Blackmailer” 1/2/55 NBC Wednesday – Aug 2nd 10pm – Adventure – LUX RADIO THEATER “The African Queen” 12/15/52 CBS 11pm – Broadway – LUX RADIO THEATER “The Letter” 3/5/44 CBS Thursday – Aug 3rd 10pm – Horror – THE SEALED BOOK “Death Rings Down the Curtain” 7/1/45 MBS LIGHTS OUT “Cat Wife” 4/6/38 NBC 11pm – Sci-Fi – X MINUS ONE “Skulking Permit” 2/15/56 NBC DIMENSION “Pebble in the Sky” 6/17/51 NBC Friday - Aug 4th 10pm – Western – TALES OF THE TEXAS RANGERS “Cold Blood” 2/17/52 NBC GUNSMOKE “Widow’s Mite” 4/8/56 CBS 11pm – Sitcom – BURNS AND ALLEN 11/8/45 NBC / AFRS DUFFY’S TAVERN 9/22/44 NBC Saturday – Aug 5th 10pm – Adventure – DANGEROUS ASSIGNMENT 6/24/53 NBC ESCAPE “Ambassador of Poker” 4/7/50 CBS 11pm – Western – GUNSMOKE “Bone Hunters” 12/11/54 CBS FRONTIER GENTLEMAN “Duel for the School Marm” 6/1/58 CBS Sunday – Aug 6th 10pm – Sitcom – PHIL HARRIS / ALICE FAYE SHOW 5/8/49 NBC ADVENTURES OF MAISIE 7/13/50 Syndicated 11pm – Sci-Fi – ARMED FORCES THEATER “Johnny Cartwright’s Camera” 7/22/44 NBC X MINUS ONE “Nightmare” 7/21/55 NBC Monday – Aug 7th 10pm – Comedy – PEOPLE ARE FUNNY “The Con Man” 1/5/54 CBS BOB HOPE SHOW “Guest: Gracie Allen” 3/25/52 NBC 11pm – True History – I AM AN AMERICAN 6/12/39 NBC THAT WAS THE YEAR “1907” 1935 Syndicated Tuesday – Aug 8th 10pm – Drama – PHILIP MORRIS PLAYHOUSE “Leona’s Room” 2/25/49 CBS ENCORE THEATER “Nurse -

Popular Western Shows from the 1950S and 1960S

Popular Western Shows From the 1950s and 1960s 1 History of the Western Genre Western themed programs were broadcast on radio and on tv throughout the 30’s, 40’s 50’s and 60’s. As the popularity rose, Westerns taught honesty, focused on values, and inspired integrity. With Westerns present in our households, many of us would tune in to listen to or watch our favorite series to follow what our hero’s had to face next. We developed a relationship with our favorite characters and followed them season after season on our favorite programs. We also looked forward to receiving the anticipated preview for the next episode. When Westerns were at their peak, there were about 30 westerns on tv in 1959. Let's take a look at some of our favorites. 2 Gunsmoke ● Ran from September 10,1955 to March 31, 1975 with 20 seasons. ● James Arness starred as Matt Dillon, Milburn Stone as Doc Galen Adams, and Amanda Blake as Kitty Russel. ● There was a radio series that lasted until 1961. ● Marshal Matt Dillon is in charge of Dodge City, a town in the wild west where people often have no respect for the law. He had to manage the problems of frontier life: cattle rustling, gunfights, brawls, standover tactics, and land fraud. 3 4 Bonanza ● Bonanza ran from September 12, 1959 - January 16, 1973 airing a total of 14 seasons. ● The show takes place in the 1860’s and is centered around the wealthy Cartwright family who lives near Virginia City, Nevada, which borders Lake Tahoe. -

Are You Hitched up and Ready for Encampment?

Volume III, Issue 2: Fall Encampment Edition Leslie Ide, Editor Are you hitched up and ready for Encampment? Each year the list of favorite events looks similar to previous years. While there are always a few additions and subtractions, I am sure this Encampment will not disappoint. Ted Faye will be back with his popular documentary programs. We have added a chuck wagon demonstration with dutch oven cooking and blacksmithing. The Encampment entertainment line up on the Fiddlers' Stage is Dave Stamey, Old West Trio, and the Messick Family. In addition, two musical offerings will be available beginning mid-October. In the tradition of Ray Parish, Steve Hohstadt (Sunset Campground) and David Ciccone (Sunset Campground Overflow) will be welcoming folks to their song circles. Susan and Kenn of Live Oak Belgians will bring back their four Belgians and a wagon or two for your riding pleasure. Chuck Knight will lead you to a few new destinations in your 4x4. Steve Hale has a new twist to this year’s historical character that you will want to see. The events are too numerous to detail in full here. Just start packing, because this Encampment promises to be a good one! See ya in Death Valley in November! Woody Adams, Encampment Program Co-Coordinator NPS Park Liaison Scholarship Endowment Chairperson President's Corner Dear Fellow ‘49ers: Welcome to the 69th Encampment of the Death Valley ‘49ers. It has been my pleasure to serve a second term as president of this fine organization, one that began with the California Centennial Celebration in 1949. -

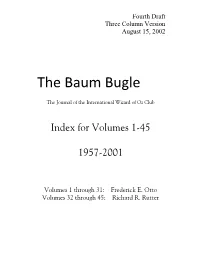

The Baum Bugle

Fourth Draft Three Column Version August 15, 2002 The Baum Bugle The Journal of the International Wizard of Oz Club Index for Volumes 1-45 1957-2001 Volumes 1 through 31: Frederick E. Otto Volumes 32 through 45: Richard R. Rutter Dedications The Baum Bugle’s editors for giving Oz fans insights into the wonderful world of Oz. Fred E. Otto [1927-95] for launching the indexing project. Peter E. Hanff for his assistance and encouragement during the creation of this third edition of The Baum Bugle Index (1957-2001). Fred M. Meyer, my mentor during more than a quarter century in Oz. Introduction Founded in 1957 by Justin G. Schiller, The International Wizard of Oz Club brings together thousands of diverse individuals interested in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and this classic’s author, L. Frank Baum. The forty-four volumes of The Baum Bugle to-date play an important rôle for the club and its members. Despite the general excellence of the journal, the lack of annual or cumulative indices, was soon recognized as a hindrance by those pursuing research related to The Wizard of Oz. The late Fred E. Otto (1925-1994) accepted the challenge of creating a Bugle index proposed by Jerry Tobias. With the assistance of Patrick Maund, Peter E. Hanff, and Karin Eads, Fred completed a first edition which included volumes 1 through 28 (1957-1984). A much improved second edition, embracing all issues through 1988, was published by Fred Otto with the assistance of Douglas G. Greene, Patrick Maund, Gregory McKean, and Peter E.