Masters of Our Time: Impatience and Self-Control in High Level Chess Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 After the Tournament

Important Dates for 2018-19 Important Changes early Sept. Chess Manual & Rule Book posted online TERMS & CONDITIONS November 1 Preliminary list of entries posted online V-E-3 Removes all restrictions on pairing teams at the state December 1 Official Entry due tournament. The result will be that teams from the same Official Entry should be submitted online by conference may be paired in any round. your school’s official representative. V- E-6 Provides that sectional tournament will only be paired There is no entry fee, but late entries will incur after registration is complete so that last-minute with- a $100 late fee. drawals can be taken into account. December 1 Updated list of entries posted online IX-G-4 Clarifies that the use of a smartwatch by a player is ille- gal, with penalties similar to the use of a cell phone. December 1 List of Participants form available online Contact your activities director for your login ID and password. VII-C-1,4,5,6 and VIII-D-1,2,4 Failure to fill out this form by the deadline con- Eliminates individual awards at all levels of the stitutes withdrawal from the tournament. tournament. Eliminates the requirement that a player stay on one board for the entire tournament. Allows January 2 Required rules video posted players to shift up and down to a different board, while January 16 Deadline to view online rules presentation remaining in the "Strength Order" declared by the Deadline to submit List of Participants (final coach prior to the start of the tournament. -

View 2020 Circular

2020 South African Junior Chess Championships 2020 Wild Card Chess Championship 2020 South Africa Junior Blitz Chess Championships 2020 South Africa Doubles Chess Championships 2020 Inter Regional Team Chess Championship 3 to 12 January 2021 Hosted by 4 Knights International Events Company CIRCULAR 1 Version 1.0 26 September 2020 Table of Contents 1. LOCAL ORGANIZING COMMITTEE (LOC) 5 1. CONVENER................................................................................................................................................. 5 2. TREASURER ................................................................................................................................................ 5 3. TECHNICAL DIRECTOR .................................................................................................................................. 5 4. CHIEF ARBITER ........................................................................................................................................... 5 5. ACCOMMODATION...................................................................................................................................... 5 6. MEDIA AND PHOTO’S .................................................................................................................................. 5 7. PUBLIC RELATIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 5 8. LOGISTICS ................................................................................................................................................. -

Super Human Chess Engine

SUPER HUMAN CHESS ENGINE FIDE Master / FIDE Trainer Charles Storey PGCE WORLD TOUR Young Masters Training Program SUPER HUMAN CHESS ENGINE Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Power Principles...................................................................................................................................... 4 Human Opening Book ............................................................................................................................. 5 ‘The Core’ Super Human Chess Engine 2020 ......................................................................................... 6 Acronym Algorthims that make The Storey Human Chess Engine ......................................................... 8 4Ps Prioritise Poorly Placed Pieces ................................................................................................... 10 CCTV Checks / Captures / Threats / Vulnerabilities ...................................................................... 11 CCTV 2.0 Checks / Checkmate Threats / Captures / Threats / Vulnerabilities ............................. 11 DAFiii Attack / Features / Initiative / I for tactics / Ideas (crazy) ................................................. 12 The Fruit Tree analysis process ............................................................................................................ -

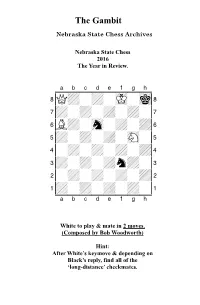

2016 Year in Review

The Gambit Nebraska State Chess Archives Nebraska State Chess 2016 The Year in Review. XABCDEFGHY 8Q+-+-mK-mk( 7+-+-+-+-' 6L+-sn-+-+& 5+-+-+-sN-% 4-+-+-+-+$ 3+-+-+n+-# 2-+-+-+-+" 1+-+-+-+-! xabcdefghy White to play & mate in 2 moves. (Composed by Bob Woodworth) Hint: After White’s keymove & depending on Black’s reply, find all of the ‘long-distance’ checkmates. Gambit Editor- Kent Nelson The Gambit serves as the official publication of the Nebraska State Chess Association and is published by the Lincoln Chess Foundation. Send all games, articles, and editorial materials to: Kent Nelson 4014 “N” St Lincoln, NE 68510 [email protected] NSCA Officers President John Hartmann Treasurer Lucy Ruf Historical Archivist Bob Woodworth Secretary Gnanasekar Arputhaswamy Webmaster Kent Smotherman Regional VPs NSCA Committee Members Vice President-Lincoln- John Linscott Vice President-Omaha- Michael Gooch Vice President (Western) Letter from NSCA President John Hartmann January 2017 Hello friends! Our beloved game finds itself at something of a crossroads here in Nebraska. On the one hand, there is much to look forward to. We have a full calendar of scholastic events coming up this spring and a slew of promising juniors to steal our rating points. We have more and better adult players playing rated chess. If you’re reading this, we probably (finally) have a functional website. And after a precarious few weeks, the Spence Chess Club here in Omaha seems to have found a new home. And yet, there is also cause for concern. It’s not clear that we will be able to have tournaments at UNO in the future. -

Quick Guide by Steven Craig Miller

A Quick Guide by Steven Craig Miller Tournament etiquette is a lot simpler than table manners . We expect Scholastic Players to always demonstrate the following basic courtesies : 1. Do your best to show up on time , as this is considerate, and extreme tardiness can cause a game to be forfeited. 2. Shake your opponent's hand as soon as you meet them at the table, tell them your name, and wish them good luck. 3. Don't talk to your opponent during the game , or answer your opponent if they speak to you, except in three cases: to say "I resign" if you want to (though this may also be accomplished simply by gently tipping your king over), to ask your opponent if they will agree to a draw , or to announce "j'doube" (or "I adjust," when straightening a piece). It is not necessary to announce "check," though you may do so if you like. If you have an important question or concern, stop both sides of the clock, raise your hand and quietly wait for a tournament official's help. 4. If your opponent refuses your offer of a draw, don't keep repeating the draw offer on each subsequent move--this is considered bad form. 5. Noisy or messy eating (or gum chewing) is not allowed . 6. Avoid making tapping noises or doing anything that may annoy or distract your opponent or the other players around you. If you encounter someone else doing something like this, and it is making it very hard for you to concentrate on the game, raise your hand for a tournament official's assistance and politely explain the situation to them. -

An Arbiter's Notebook

10.2 Again Purchases from our shop help keep ChessCafe.com freely accessible: Question: Dear, Mr. Gijssen. I was playing in a tournament and the board next to me played this game: 1.Nf3 Nf6 2.Ng1 Ng8 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Ng1 Ng8. When a draw was claimed, the arbiter demanded that both players replay the game. When one of them refused, the arbiter forfeited them. Does the opening position count for purposes of threefold repetition? Matthew Larson (UK) Answer In my opinion, the arbiter was right not to accept this game. I refer to Article 12.1 of the Laws of Chess: An Arbiter’s The players shall take no action that will bring the game of chess into disrepute. Notebook To produce a "game" as mentioned in your letter brings the game of chess The Greatest Tournaments into disrepute. The only element in your letter that puzzles me is the fact that Geurt Gijssen 2001-2009 the arbiter forfeited both players, although only one refused to play a new by Chess Informant game. The question of the threefold repetition is immaterial in this case. Question Greetings, Mr. Gijssen. I acted as a member of the appeals committee in a rapid chess tournament (G60/sudden death). I also won that tournament, but I am not a strong player, just 2100 FIDE, with a good understanding of the rules. The incident is as follows: A player lost a game and signed the score sheet, and then he appealed the decision of the arbiter to the committee with regards to some bad rulings during the game. -

Regulations for the Chess Olympiad

D.II. Chess Olympiad D.II.01 Regulations for the Chess Olympiad 1. General 1.1 The Chess Olympiad is the principal team contest organized by FIDE. 1.1.1 The Olympiad is held regularly at two year intervals in the autumn of the even numbered years (2006, 2008, etc.) 1.1.2 The Olympiad for both the open section and the women section must be held, if possible, at a single venue. 1.1.3 However, in exceptional cases as determined by the FIDE General Assembly or (in between congresses) by the President - separate venues may be used for the men and women contests. 1.1.4 Organizing body: FIDE, represented by the FIDE President. 1.1.5 Administrator 1.1.5.1 The administrator is appointed through a special selection process (section 2 below). 1.1.5.2 The administrator is responsible to FIDE, and must abide by these regulations. 1.1.5.3 The administrator shall make available all necessary premises, staff and funds for the contest. The minimum requirements are laid down in individual sections of these regulations. 1.1.5.4 The administrator may utilize the services of outside bodies or private persons for the purpose of financing and running the contest. 1.1.5.5 Administrators may be proposed by the federations. 1.1.5.6 The President may also receive offers from sponsors outside the sphere of FIDE. 1.1.5.7 The tasks of the administrator are detailed in subsequent sections of these regulations. 1.1.6 FIDE Congress The administrator who undertakes the running of the Chess Olympiad must also undertake to hold the FIDE Congress for the same year. -

An Arbiter's Notebook

What is a Valid Claim? Purchases from our shop help keep ChessCafe.com freely accessible: Question Dear, Geurt. I was the Arbiter in Grandmaster Group C during the Corus Chess tournament. I was able to observe the way players handled the new speed of play: 40 moves in 100', followed by 20 in 50', followed by 15', while there was an increment of 30 seconds per move starting from move one. When not in time trouble, thirteen out of fourteen players recorded their move immediately after having made it, or after their opponent's move; one player recorded her opponent's move together with her own move, directly after having made a move herself. An Arbiter’s However, when in time trouble, with a recording requirement till the end, this Notebook changed. Many of the players now recorded their moves the way player fourteen did from the beginning. But four players in different rounds started to Play Chess Like the Pros blitz illegally when their opponent answered a move immediately in a legal by Danny Gormally Geurt Gijssen way. Undoubtedly, this is caused by the fact that in games without increment it is allowed to blitz without recording moves when a player has less than five minutes for that part of the game. Once a player even had to stop the clock and ask for assistance. His opponent had started blitzing, triggered by an immediate answer; actually I am convinced that the player who started the blitzing was not doing this on purpose. Players in time trouble, filled with adrenaline, are eager to make an immediate counter-move. -

2020 FISU World University Championship Mind Sports Online Regulations

2020 FISU World University Championship Mind Sports online Regulations 2020 FISU WUC Mind Sports online Regulations Contents 1. Event Regulations........................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 General terms ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Pre-competition procedure ............................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Registration ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.2 Competition timeline ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Technical requirements ................................................................................................................. 4 3. Competition .................................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Competition programme .............................................................................................................................................. 4 3.2 System of competition .................................................................................................................................................. -

Starting Out: the Sicilian JOHN EMMS

starting out: the sicilian JOHN EMMS EVERYMAN CHESS Everyman Publishers pic www.everymanbooks.com First published 2002 by Everyman Publishers pIc, formerly Cadogan Books pIc, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD Copyright © 2002 John Emms Reprinted 2002 The right of John Emms to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 857442490 Distributed in North America by The Globe Pequot Press, P.O Box 480, 246 Goose Lane, Guilford, CT 06437·0480. All other sales enquiries should be directed to Everyman Chess, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD tel: 020 7539 7600 fax: 020 7379 4060 email: [email protected] website: www.everymanbooks.com EVERYMAN CHESS SERIES (formerly Cadogan Chess) Chief Advisor: Garry Kasparov Commissioning editor: Byron Jacobs Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton Production by Book Production Services Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd., Trowbridge, Wiltshire Everyman Chess Starting Out Opening Guides: 1857442342 Starting Out: The King's Indian Joe Gallagher 1857442296 -

1) the Team Listed First Has White on Boards 1 and 3. 2) All Teams

Rules 1) The team listed first has White on Boards 1 and 3. 2) All teams must play in rating order, unrateds below all rated players. Unrateds may play in any order, but order may not subsequently be changed. 3) Both Team Captains are responsible for turning in the result sheet. If the Captain must leave, he should assign another team member as acting captain to sign and submit the result sheet. 4) A player may ask his Captain whether to offer or accept a draw. The Captain may reply based on the match standing. The Captain may not give advice based on the position on the board (or allow any appearance of doing so). The player is not obligated to accept the Captain's advice. 5) Black has his choice of standard equipment, except that digital time delay clocks with the time delay in effect are always preferred.. 6) If a player wishes to use a digital clock, it is his responsibility to set the clock and explain all of its functions to the opponent. If you can’t, find another clock.. 7) In order to claim a win on time, a player must present a legible score sheet correct to within three move pairs at the time the opponent’s flag falls. Moves filled in after this do not count. A missing move or check mark for either White’s or Black’s move counts as one missing move pair. So does an unreadable or ambiguous move earlier in the game. Minor notation errors which do not affect playability do not count as errors. -

Double Fianchetto – the Modern Chess Lifestyle

DOUBLE-FIANCHETTO THE MODERN CHESS LIFESTYLE by Daniel Hausrath www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor Romain Edouard Assistant Editor Daniel Vanheirzeele Graphic Artist Philippe Tonnard Cover design Iwan Kerkhof Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2020 by Th inkers Publishing Double-Fianchetto — the Modern Chess Lifestyle Copyright © 2020 Daniel Hausrath All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-94-9251-075-4 D/2020/13730/3 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Th inkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.thinkerspublishing.com TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO SYMBOLS 5 PREFACE 7 PART 1. DOUBLE FIANCHETTO WITH WHITE 9 Chapter 1. Double fi anchetto against the King’s Indian and Grünfeld 11 Chapter 2. Double fi anchetto structures against the Dutch 59 Chapter 3. Double fi anchetto against the Queen’s Gambit and Tarrasch 77 Chapter 4. Diff erent move orders to reach the Double Fianchetto 97 Chapter 5. Diff erent resulting positions from the Double Fianchetto and theoretically-important nuances 115 PART 2. DOUBLE FIANCHETTO WITH BLACK 143 Chapter 1. Double fi anchetto in the Accelerated Dragon 145 Chapter 2. Double fi anchetto in the Caro Kann 153 Chapter 3. Double fi anchetto in the Modern 163 Chapter 4. Double fi anchetto in the “Hippo” 187 Chapter 5. Double fi anchetto against 1.d4 205 Chapter 6. Double fi anchetto in the Fischer System 231 Chapter 7.