Inclusive Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flower Route Map 2014 LR

K o n k i e p en w R31 Lö Narubis Vredeshoop Gawachub R360 Grünau Karasburg Rosh Pinah R360 Ariamsvlei R32 e N14 ng Ora N10 Upington N10 IAi-IAis/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park Augrabies N14 e g Keimoes Kuboes n a Oranjemund r Flower Hotlines O H a ib R359 Holgat Kakamas Alexander Bay Nababeep N14 Nature Reserve R358 Groblershoop N8 N8 Or a For up-to-date information on where to see the Vioolsdrif nge H R27 VIEWING TIPS best owers, please call: Eksteenfontein a r t e b e e Namakwa +27 (0)79 294 7260 N7 i s Pella t Lekkersing t Brak u West Coast +27 (0)72 938 8186 o N10 Pofadder S R383 R383 Aggeneys Flower Hour i R382 Kenhardt To view the owers at their best, choose the hottest Steinkopf R363 Port Nolloth N14 Marydale time of the day, which is from 11h00 to 15h00. It’s the s in extended ower power hour. Respect the ower Tu McDougall’s Bay paradise: Walk with care and don’t trample plants R358 unnecessarily. Please don’t pick any buds, bulbs or N10 specimens, nor disturb any sensitive dune areas. Concordia R361 R355 Nababeep Okiep DISTANCE TABLE Prieska Goegap Nature Reserve Sun Run fels Molyneux Buf R355 Springbok R27 The owers always face the sun. Try and drive towards Nature Reserve Grootmis R355 the sun to enjoy nature’s dazzling display. When viewing Kleinzee Naries i R357 i owers on foot, stand with the sun behind your back. R361 Copperton Certain owers don’t open when it’s overcast. -

National Road N12 Section 6: Victoria West to Britstown

STAATSKOERANT, 15 OKTOBER 2010 NO.33630 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT No. 904 15 October 2010 THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL ROADS AGENCY LIMITED Registration No: 98109584106 DECLARATION AMENDMENT OF NATIONAL ROAD N12 SECTION 6 AMENDMENT OF DECLARATION No. 631 OF 2005 By virtue of section 40(1)(b) of the South African National Roads Agency Limited and the National Roads Act, 1998 (Act NO.7 of 1998), I hereby amend Declaration No. 631 of 2005, by substituting the descriptive section of the route from Victoria West up to Britstown, with the subjoined sheets 1 to 27 of Plan No. P727/08. (National Road N12 Section 6: Victoria West - Britstown) VI ~/ o8 ~I ~ ~ ... ... CD +' +' f->< >< >< lli.S..E..I VICTORIA WEST / Ul ~ '-l Ul ;Ii; o o -// m y 250 »JJ z _-i ERF 2614 U1 iii,..:.. "- \D o lL. C\J a Q:: lL. _<n lLJ ~ Q:: OJ olLJ lL. m ~ Q:: Q) lLJ JJ N12/5 lL. ~ fj- Q:: ~ I\J a DECLARATION VICTORIA lLJ ... ... .... PLAN No. P745/09 +' a REM 550 +' :£ >< y -/7 0 >< WEST >< 25 Vel von stel die podreserwe voor von 'n gedeelte Z Die Suid Afrikoonse Nosionole Podogentskop 8eperk Die figuur getoon Sheet 1 of 27 a represents the rood reserve of 0 portion ~:~:~:~: ~ :~: ~:~:~:~:~:~ The figure shown w The South African Notional Roods Agency Limited ........... von Nosionole Roete Seksie 6 Plan w :.:-:-:-:.:.:-:.:-:-:.: N12 OJ of Notional Route Section P727108 w a D.O.9.A • U1 01 o II') g 01' ICTORIA0' z " o o (i: WEST \V II> ..... REM ERF 9~5 II') w ... -

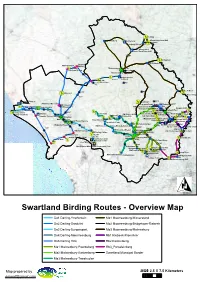

Swartland Birding Routes - Overview Map

!FDe Brug &RM Koringberg .!Koringberg Misverstand Dam Wall !F &RM Misverstand Koringberg Hiking Trails !F &RM N7 Misverstand :I Desert Rose Farm Stall K$ N7 !FBridgetown &RM Bridgetown Sandvlei RM Sandvlei N&!F&RM R45 &!FSout River Moorreesburg N7 Ganskraal Siding .!MKoo$rreesburg MoorreesburgTM Moorreesburg K$ R45 & !F !FRM R307-Main Stre Wetland Neulfontein &RM Da!Frling SW RK$45 and R307BS De Panne K$ N7 R45 &RM Riebeek West $ R 307 K$ R311 Kikoesvlei K !F !F K$ Berg River Bridge R3071 Blombos Hiking Tr Radyn Dam K$ R311 I BS Blombos !F !F: Hildebrand Monument RM Riebeek Rd-R311 &&RM Kikoesvlei 2 Ongegund/Smuts House Salt Pan Lime Kiln 1 \! Voorsp&oed Dam !F Tienie Versfeld RM Kikoesvlei 1 RM Riebeecksrivier Rd& \! & K$&R315 ! Voorspoed DamRM Riebee&k Rd R311 Zanquas Drift & \! R 27± K$ R K$315a !F Riebeek West RM BlombosRM Saltpan RM P!FPCK $Rd !F K$ R315 !F Horus Swift !F!FSchaap Island K$ R307 !FRi$ebeeksrivi.!er Dam1 RM DeliCo RIM Khwattu RM R315 Seasonal Pond RM Riebeeck Rd Riebeeksrivier RdK Small Vlei !FVis River Schaap Island Tra : K$ $ Seasonal Pan Oak Valley Dam !F& & Khwattu Cultural AreaK& & &RM Rd to R45 & Oak Valley Dam!F !F R.!307TM Darling !F :I& Riebee!Fk-Kasteel!F & !F !F RM Vyevlei Middelpos Dam Kloovenburg &&!F Darling$T$M Darling Vyevlei Dam !F .!&&R&M;I R311-R46Farm Dam KK Small Stream :I Pieter C!Fruythoff & R!3&07Oude$post Flower Reserve K$ K$;I&R 46!FEbenhaeser Dam& ± !K Spekulasie Farm $&R46 R46 ± R 307 R45 &FRM N7-Rheboksfontein K !F Waylands Flower Res & ! RM Riebeeksrivier-RK46$ R46 K$ RM Rondevlei-SpekulasieRheboksfontein Dam& $ R46. -

Getting Beyond the E-Toll Impasse

GETTING BEYOND THE E-TOLL IMPASSE August 2019 Initially compiled in September 2014 and titled “Beyond the Impasse” by Wayne Duvenage (OUTA Chairperson) and John Clarke (Consultant Social Worker), for presentation to Premier David Makhura’s Gauteng Advisory Panel on Socio-economic Impact of e-tolls. This position paper has now been updated and revised in August 2019 under an amended title: “Getting Beyond the e-toll Impasse” updated by Wayne Duvenage & Rudie Heyneke 1 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page 3 2. INTRODUCTION & SETTING THE SCENE Page 5 3. DEFINITIONS, EXPLANATIONS & CLARIFICATIONS Page 7 • The South African Roads Agency Page 7 • Types of Tolls in SA Page 8 • E-tolls and Intelligent Transport Systems (I.T.S.) Page 9 • The User-Pays Principle. Page 10 4. HISTORY OF THE E-TOLL SAGA Page 11 5. GAUTENG’s E-TOLL CHALLENGES Page 26 • Grounds for opposition to e-tolling of GFIP Page 28 6. FACTORS FOR SUCCESSFUL ‘USER PAY’ I.T.S. Page 37 7. INTERNATIONAL EXAMPLES & CASE STUDIES Page 43 8. GOVERNMENT IN A CRISIS OF LEGITIMACY ON E-TOLLS Page 48 9. THE WAY FORWARD Page 50 • OUTA’s Proposals Page 51 10. CONCLUSION Page 54 11. GLOSSARY & ABBREVIATIONS Page 55 12. BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 56 ANNEXURES: A: ETC Contract Value for e-toll Operations Services. Page 57 B: ETC-JV Tender value. Page 58 C: List of types of e-toll billing Errors. Page 59 D: FUEL LEVY Revenue and Fuel Volumes sold. Page 60 E: Department of Transport Memo to Cabinet – Page 61 Gauteng’s Economic Value to SA. -

Tender Bulletin REPUBLICREPUBLIC of of SOUTH SOUTH AFRICAAFRICA

Government Tender Bulletin REPUBLICREPUBLIC OF OF SOUTH SOUTH AFRICAAFRICA Vol. 598 Pretoria, 17 April 2015 No. 2864 This document is also available on the Internet on the following web sites: 1. http://www.treasury.gov.za 2. http://www.info.gov.za/documents/tenders/index.htm 3. http://www.gpwonline.co.za N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINEHELPLINE: 08000800-123-22 123 22 PreventionPrevention is is the the curecure 501241— A 2864— 1 2 GOVERNMENT TENDER BULLETIN, 17 APRIL 2015 INDEX Page No. Instructions.................................................................................................................................. 8 A. BID INVITED FOR SUPPLIES, SERVICES AND DISPOSALS SUPPLIES: CLOTHING/TEXTILES .................................................................................. 10 ١ SUPPLIES: ELECTRICAL EQUIPMENT .......................................................................... 10 ١ SUPPLIES: GENERAL...................................................................................................... 11 ١ SUPPLIES: MEDICAL ....................................................................................................... 28 ١ SUPPLIES: PERISHABLE PROVISIONS......................................................................... 33 ١ SUPPLIES: STATIONERY/PRINTING .............................................................................. 35 ١ SERVICES: BUILDING .................................................................................................... -

Local Government AR 12

Annual Report 2011/2012 Department of Local Government Department of Local Government Vote 14 Annual Report 2011/12 Provincial Government Western Cape Mr Anton Bredell Minister of Local Government, Environmental Affairs and Development Planning I have the honour of submitting the Annual Report of the Department of Local Government for the period 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012. H Fast 31 August 2012 Annual Report 2011/12 List of Abbreviations in Annual Report AC: Accounting Officer MDB: Municipal Demarcation Board ACC: Anti-Corruption (Ethics) Committees MEC: Member of the Executive Council ACSA: Airports Company South Africa MFMA: Municipal Finance Management Act, 2003 AFS: Annual Financial Statements (Act 56 of 2003) APP: Annual Performance Plan MIG: Municipal Infrastructure Grant BAS: Basic Accounting System MINMAY: Forum of Provincial Minister of Local CAPS: Category of Authorised Persons Government & Executive Mayors CBOs: Community Based Organisation MINMAYTECH: Forum of the Head of Department: CDW: Community Development Worker Local Government & Municipal Managers CF: Communication Forums MIS MIG: Management Information System, CSC: Corporate Service Centre Municipal Infrastructure Grant DCAS: Department of Cultural Affairs & Sport MM: Municipal Manager DCF: District Co-ordinating Forum MoU: Memorandum of Understanding DCOG: Department of Co-operative Governance MPM: Municipal Performance Monitoring DBSA: Development Bank of South Africa MPRA: Municipal Property Rates Act, 2004 (Act 6 DHS: Department of Human Settlements of 2004) -

Flower Route Map 2017

K o n k i e p en w R31 Lö Narubis Vredeshoop Gawachub R360 Grünau Karasburg Rosh Pinah R360 Ariamsvlei R32 e N14 ng Ora N10 Upington N10 IAi-IAis/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park Augrabies N14 e g Keimoes Kuboes n a Oranjemund r Flower Hotlines O H a ib R359 Holgat Kakamas Alexander Bay Nababeep N14 Nature Reserve R358 Groblershoop N8 N8 Or a For up-to-date information on where to see the Vioolsdrif nge H R27 VIEWING TIPS best owers, please call: Eksteenfontein a r t e b e e Namakwa +27 (0)72 760 6019 N7 i s Pella t Lekkersing t Brak u Weskus +27 (0)63 724 6203 o N10 Pofadder S R383 R383 Aggeneys Flower Hour i R382 Kenhardt To view the owers at their best, choose the hottest Steinkopf R363 Port Nolloth N14 Marydale time of the day, which is from 11h00 to 15h00. It’s the s in extended ower power hour. Respect the ower Tu McDougall’s Bay paradise: Walk with care and don’t trample plants R358 unnecessarily. Please don’t pick any buds, bulbs or N10 specimens, nor disturb any sensitive dune areas. Concordia R361 R355 Nababeep Okiep DISTANCE TABLE Prieska Goegap Nature Reserve Sun Run fels Molyneux Buf R355 Springbok R27 The owers always face the sun. Try and drive towards Nature Reserve Grootmis R355 the sun to enjoy nature’s dazzling display. When viewing Kleinzee Naries i R357 i owers on foot, stand with the sun behind your back. R361 Copperton Certain owers don’t open when it’s overcast. -

Market Inquiry Into Land Based Public Passenger Transport Main Report

MARKET INQUIRY INTO LAND BASED PUBLIC PASSENGER TRANSPORT MAIN REPORT NON-CONFIDENTIAL VERSION 19 February 2020 i Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... ii List of figures .......................................................................................................................................... iv List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................ v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 1 1. MARKET INQUIRY PROCESS................................................................................................... 1 2. BACKGROUND TO THE PUBLIC TRANSPORT SECTOR IN SOUTH AFRICA ...................... 9 3. REGULATORY FRAMEWORK................................................................................................. 26 4. PUBLIC TRANSPORT AS AN INTEGRATED SYSTEM .......................................................... 41 5. SUBSIDIES IN THE PUBLIC TRANSPORT SECTOR ............................................................. 61 6. THE RAIL SECTOR .................................................................................................................. 91 7. SUBSIDISED BUS CONTRACTS IN URBAN AREAS ........................................................... 126 8. RURAL TRANSPORTATION AND -

Industrial Policy Action Plan (IPAP)

INDUSTRIAL POLICY ACTION PLAN Economic sectors, employment and infrastructure development cluster 2018/19 - 2020/21 Economic Analysis 10-year Legacy Review Key Constraints on Industrial Policy Transversal and Sector Focus Areas with Key Action Programmes towards full-scale industrialisation and inclusive growth the dti Customer Contact Centre: 0861 843 384 Website: www.thedti.gov.za © Department of Trade and Industry, May 2018 Photos are courtesy of the dti image library the dti Campus 77 Meintjies Street Sunnyside Pretoria 0002 the dti Private Bag X84 Pretoria 0001 the dti Customer Contact Centre: 0861 843 384 the dti Website: www.thedti.gov.za ISBN: 978-0-621-46268-5 RP: 109/2018 Contents FOREWORD BY THE MINISTER OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY ....................................................................................................................................................................................................4 A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR-GENERAL .........................................................................................................................................................................................................................9 IPAP IN CONTEXT: ECONOMIC ANALYSIS ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................10 10 YEARS OF IPAP: A LEGACY REPORT ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................28 -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant April Vol. 646 18 2019 No. 42405 April ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 42405 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 42405 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 18 APRIL 2019 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Contents Page No. Transport, Department of Cross-Border Road Transport Agency: Applications for Permits Menlyn .............................................................................................................................................................................3 Applications concerning Operating Licences Goodwood ..................................................................................................................................................................... 15 This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 18 APRIL 2019 No. 42405 3 Transport, Department of Cross-Border Road Transport Agency: Applications for Permits Menlyn CROSS-BORDER ROAD TRANSPORT AGENCY APPLICATIONS FOR PERMITS Particulars in respect of applications for permits as submitted to the Cross-Border Road Transport -

2020 QUARTER 3 (July–September)

Economic Performance Indicators for Cape Town 2020 QUARTER 3 (July–September) WWW.INVESTCAPETOWN.COM EPIC 2020: Q3 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The EPIC quarterly publication is a collaboration between the Enterprise and Investment, and Policy and Strategy departments of the City of Cape Town. The EPIC publication presents and analyses economic (and related) trends in Cape Town on a quarterly basis. This edition focuses on the third quarter of 2020, covering the period 1 July to 30 September 2020. ECONOMIC CONTENT AUTHORED BY THE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS BRANCH, POLICY AND STRATEGY DEPARTMENT Manager: Economic Analysis: Paul Court Project manager and author: Dilshaad Gallie Additional authors: Alfred Moyo Monique Petersen Jodie Posen Yoliswa Tiwe MARKETING, DESIGN AND DISTRIBUTION BY THE INVEST CAPE TOWN TEAM, ENTERPRISE AND INVESTMENT DEPARTMENT Manager: Place Marketing: Rory Viljoen Project manager: Tarryn Voigt-Mallum Success stories: Caryn Jeftha HelloFCB Kim Whitaker Email: [email protected] [email protected] Online access: www.capetown.gov.za/EPIC ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION City of Cape Town Planning and Building Development Management: Marius Crous Lizanne Ryneveldt City of Cape Town Electricity Generation and Distribution: Cornie Malan 2 EPIC 2020: Q3 FOREWORD Although the full effect of the various stages of Even before Covid-19, many businesses found the national lockdown is yet to be quantified, the themselves in distress, and the pandemic has short-term costs for the economy have been dire. exacerbated this situation. The challenges are Early on in the global Covid-19 pandemic, I set up not just financial, as most of these businesses an essential task team to work on our response are struggling with productivity, or streamlining to the impact of the lockdown measures. -

2010 Developer Guide

2010 Developer’s Guide Town of Fountain Hills Development Services Department 1 | Page Town of Fountain Hills Developer’s Guide Town Council Jay Schlum, Mayor Dennis Brown, Vice Mayor Dennis Contino, Councilmember Ginny Dickey, Councilmember Tait Elkie, Councilmember Cassie Hansen, Councilmember Henry Leger, Councilmember Richard Davis, Town Manager Prepared by Town of Fountain Hills Development Services Department August 2010 2 | Page Preface and Acknowledgements This Developer’s Guide has been prepared to assist future builders, contractors, and developers in preparing applications for Town of Fountain Hills permits. This book provides a step-by-step process for acquiring permits and generates fewer questions for Town Departments as well as minimizes applicant confusion. In addition to this Guide, it will be beneficial for the builder, contractor, or developer to discuss the project with people in various Town departments. This will allow the Town to become familiar with the ideas and goals, thereby creating a smooth transition to obtaining the necessary permits. If additional questions or concerns arise, the Town of Fountain Hills will be better equipped to assist. The fee schedule in Chapter 9 of the Developer’s Guide is subject to change and should be verified. Please note that this Guide is published only as a source of helpful information and does not supersede actual regulations adopted by the Town Council. Town of Fountain Hills 16705 East Avenue of the Fountains Fountain Hills, Arizona 85268 Telephone: 480-816-5100 Fax: 480-837-3145