Protecting Florida's Springs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preserving Florida's Heritage

Preserving Florida’s Heritage MMoorree TThhaann OOrraannggee MMaarrmmaallaaddee Florida’s Comprehensive Historic Preservation Plan 2012 - 2016 Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION Page 1 Viva Florida Why Have a Statewide Historic Preservation Plan? CHAPTER 1 OVERVIEW OF FLORIDA’S PRE-HISTORY & HISTORY Page 4 CHAPTER 2 PLANNING IN FLORIDA, A PUBLIC POLICY Page 8 CHAPTER 3 PRESERVATION PARTNERS Page 12 Federal Government Seminole Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) State Government Other Florida Department of State Programs Advisory Boards and Support Organizations Other State Agencies Formal Historic Preservation Academic Programs Local Governments Non-Profit Organizations CHAPTER 4 FLORIDA’S RESOURCES, AN ASSESSMENT Page 36 Recent Past Historic Landscapes Urbanization and Suburbanization Results from Statewide Survey of Local Historic Preservation Programs African-American Resources Hispanic Resources Transportation Religion Maritime Resources Military Recreation and Tourism Industrialization Folklife Resources CHAPTER 5 HOW THIS PLAN WAS DEVELOPED Page 47 Public Survey Survey Results Meetings Findings Timeframe of the Plan and Revisions CHAPTER 6 GOALS, OBJECTIVES, AND SUGGESTED STRATEGIES Page 53 Vision Statement for Historic Preservation in Florida CHAPTER 7 A BRIEF TIMELINE OF FLORIDA HISTORY Page 63 CHAPTER 8 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND OTHER RESOURCES Page 71 BIBLIOGRAPHY USEFUL LINKS FLORIDA’S HISTORICAL CONTEXTS MULTIPLE PROPERTY SUBMISSION COVERS Archaeological Thematic or Property Types Local Areas HERITAGE TRAILS SOCIAL MEDIA ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The preparation of a statewide comprehensive historic preservation plan intended for everyone across the state involved many people. We are greatly appreciative of the regional staff from the Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN) who hosted public meetings in five communities across the state, and to Jeannette Peters, the consultant who so ably led those meetings. -

Table of Contents

FLORIDA Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan SEPTEMBER 2008 (Originally submitted October 2006) Prepared by: Florida Coastal Management Program In cooperation with: Florida Department of Environmental Protection Division of State Lands Office of Coastal and Aquatic Managed Areas Florida Natural Areas Inventory ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many state partners and individuals assisted the Florida Coastal Management Program in developing the Florida Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan. The Florida Coastal Management Program would like to extend special thanks to the following for their assistance and support in developing this plan: From the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Division of State Lands O. Greg Brock, Donna Jones Ruffner and Ellen Stere From the Florida Natural Areas Inventory Gary Knight and Ann F. Johnson The Florida Coastal Management Program 3900 Commonwealth Blvd. MS #47 Tallahassee, FL 32399 Coastal Program URL: http://www.dep.state.fl.us/mainpage/programs/cmp.htm Development of this plan was supported with funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management under Section 306 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972. Florida Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan Overview of conservation lands in the State of Florida ii Florida Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 a. Background -

FLORIDA STATE PARKS FEE SCHEDULE (Fees Are Per Day Unless Otherwise Noted) 1. Statewide Fees Admission Range $1.00**

FLORIDA STATE PARKS FEE SCHEDULE (Fees are per day unless otherwise noted) 1. Statewide Fees Admission Range $1.00** - $10.00** (Does not include buses or admission to Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park or Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) Single-Occupant Vehicle or Motorcycle Admission $4.00 - $6.00** (Includes motorcycles with one or more riders and vehicles with one occupant) Per Vehicle Admission $5.00 - $10.00** (Allows admission for 2 to 8 people per vehicle; over 8 people requires additional per person fees) Pedestrians, Bicyclists, Per Passenger Exceeding 8 Per Vehicle; Per $2.00 - $5.00** Passenger In Vehicles With Holder of Annual Individual Entrance Pass Admission Economically Disadvantaged Admission One-half of base (Must be Florida resident admission fee** and currently participating in Food Stamp Program) Bus Tour Admission $2.00** per person (Does not include Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park, or $60.00 Skyway Fishing Pier State Park, or Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) whichever is less Honor Park Admission Per Vehicle $2.00 - $10.00** Pedestrians and Bicyclists $2.00 - $5.00** Sunset Admission $4.00 - $10.00** (Per vehicle, one hour before closing) Florida National Guard Admission One-half of base (Active members, spouses, and minor children; validation required) admission fee** Children, under 6 years of age Free (All parks) Annual Entrance Pass Fee Range $20.00 - $500.00 Individual Annual Entrance Pass $60.00 (Retired U. S. military, honorably discharged veterans, active-duty $45.00 U. S. military and reservists; validation required) Family Annual Entrance Pass $120.00 (maximum of 8 people in a group; only allows up to 2 people at Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park and Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) (Retired U. -

Curriculum Vitae Joseph N. Boyer, Director

Curriculum Vitae Joseph N. Boyer, Director Southeast Environmental Research Center 305-348-4076 (Office) OE-148 305-348-4096 (FAX) Florida International University 305-606-6874 (cell) Miami, FL 33199 [email protected] Professional Experience 2010-present Associate Professor, Dept. of Earth & Environment, FIU 2009-present Director, SERC, FIU 2003-2009 Associate Director, SERC, FIU 2001-2009 Associate Scholar/Scientist. SERC, FIU 1995-2001 Assistant Scholar/Scientist. SERC, FIU 1992-1995 Postdoctoral Ecologist. Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, NY 1994 Instructor. Bard College, NY 1990-1992 Aquatic Biologist. Waterline Ltd., Prince Edward Island, Canada 1989-1990 Instructor. Biology Dept., East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 1987-1990 Assistant Scientist. Institute for Coastal and Marine Resources, ECU 1986-1987 Marine Scientist A. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary Education Ph.D. Marine Science, 1987, College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA Dissertation: Degradation and Mineralization of Chitin in an Estuary B.S. Microbiology, 1978, The American University, Washington, DC Professional Activities Scientific Advisory Panel/Board Membership Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council (SAC) FDEP Numeric Nutrient Criteria Technical Advisory Committee (MTAC) FIU representative to the Florida Coastal Ocean Observing System Caucus (FLCOOS) FIU representative to the Florida Institute of Oceanography Council (FIO) Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Technical Advisory Committee Southeast Florida Coral -

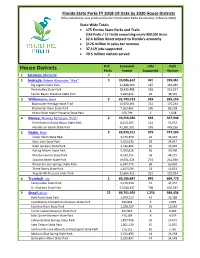

Florida State Parks Data by 2021 House District

30, Florida State Parks FY 2019-20 Data by 2021 House Districts This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation . FloridaStateParksFoundation.org Statewide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.2 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $150 million in sales tax revenue • 31,810 jobs supported • 25 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 31,073,188 436 349,462 Big Lagoon State Park 10,336,536 145 110,254 Perdido Key State Park 17,191,206 241 198,276 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,545,446 50 40,932 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 26,651,285 416 362,492 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 18,971,114 266 218,287 Blackwater River State Park 7,101,563 99 78,680 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 578,608 51 65,525 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 41,626,278 583 469,477 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,558,966 106 83,636 Henderson Beach State Park 34,067,312 477 385,841 5 Drake, Brad 9 64,140,859 897 696,022 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 Deer Lake State Park 1,738,073 24 19,557 Eden Gardens State Park 3,235,182 45 36,128 Falling Waters State Park 5,510,029 77 58,866 Florida Caverns State Park 4,090,576 57 39,405 Grayton Beach State Park 17,072,108 239 186,686 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,911,495 97 78,277 Three Rivers State Park 2,916,005 41 30,637 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 19,533,681 273 213,693 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 45,103,015 632 504,860 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 St. -

30, House Districts

30, Florida State Parks FY 2018-19 Data by 2020 House Districts (This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, February 2020) . State Wide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.6 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $176 million in sales tax revenue • 37,119 jobs supported • 29.5 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 35,086,662 491 399,461 Big Lagoon State Park 13,388,360 187 146,049 Perdido Key State Park 18,435,488 258 215,257 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,262,814 46 38,155 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 22,793,752 319 262,150 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 15,070,491 211 175,244 Blackwater River State Park 7,562,462 106 85,258 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 160,799 2 1,648 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 49,456,096 692 567,948 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 8,154,105 114 91,652 Henderson Beach State Park 41,301,991 578 476,296 5 Drake, Brad 9 69,939,012 979 747,560 Camp Helen State Park 3,176,350 44 34,444 Deer Lake State Park 2,102,533 29 24,057 Eden Gardens State Park 3,186,404 45 35,924 Falling Waters State Park 5,760,818 81 59,390 Florida Caverns State Park 4,532,155 63 44,215 Grayton Beach State Park 19,551,524 274 212,050 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,347,774 89 69,063 Three Rivers State Park 1,617,039 23 15,653 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 23,664,415 331 252,764 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 60,186,687 842 684,779 Camp Helen State Park 3,176,350 44 34,444 St. -

FLORIDA: Guide to Living on the Space Coast & Fun in the Sunshine State!

FLORIDA: Guide to Living on the Space Coast & Fun in the Sunshine State! By Pam Winegar ➢ Our nature photography blog is at: https://naturetime.wordpress.com/ ➢ Ask to join Pam’s e-mail photo-of-the-day at: [email protected] Updated January 24, 2018 Contents LOCAL PALM BAY/MELBOURNE BASICS ...................................................................................................... 1 BREVARD COUNTY BASICS .......................................................................................................................... 1 WEATHER .................................................................................................................................................... 5 AREA WEBSITES .......................................................................................................................................... 6 LIVE WEBCAMS ........................................................................................................................................... 6 SPACE COAST FUN ...................................................................................................................................... 7 BEACHES ................................................................................................................................................. 7 NATURE OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................................. 11 LAGOON ACTIVITIES ............................................................................................................................. -

House Districts (This Compilation Was Produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, January 2019)

Florida State Parks FY 2017-18 Data by 2019 House Districts (This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, January 2019) . State Wide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.4 billion direct economic impact • $158 million in sales tax revenue • 33,587 jobs supported • Over 28 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Hill, Walter Bryan “Mike” 0 2 Andre, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 28,135,146 393 338,807 Big Lagoon State Park 12,155,746 170 141,517 Perdido Key State Park 12,739,427 178 157,126 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,239,973 45 40,164 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 22,545,992 315 275,195 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 15,301,348 214 188,630 Blackwater River State Park 6,361,036 89 75,848 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 883,608 12 10,717 4 Ponder, Mel 2 46,877,022 657 564,936 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,896,093 111 88,633 Henderson Beach State Park 38,980,929 546 476,303 5 Drake, Brad 9 75,811,647 1062 881,589 Camp Helen State Park 2,778,378 39 31,704 Deer Lake State Park 1,654,544 23 19,939 Eden Gardens State Park 3,298,681 46 39,601 Falling Waters State Park 5,761,074 81 67,225 Florida Caverns State Park 12,217,659 171 135,677 Grayton Beach State Park 20,250,255 284 236,181 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 4,745,495 66 57,194 Three Rivers State Park 3,465,975 49 39,482 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 21,639,586 303 254,586 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 76,186,412 1,067 926,162 Camp Helen State Park 2,778,378 39 31,704 St. -

Springs TMDL of Coastal Hernando and Pasco

SOUTHWEST DISTRICT • SPRINGS COAST BASIN FINAL TMDL Report Nutrient TMDLs for Coastal Springs of Pasco and Hernando Counties: Magnolia–Aripeka Springs Group, Jenkins Creek Spring, Wilderness–Mud–Salt Springs Group, (WBIDs 1391B, 1389, and 1382G) and Documentation in Support of Development of Site-Specific Numeric Interpretations of the Narrative Nutrient Criterion Kristina Bridger and James Dodson Ground Water Management Section Division of Environmental Assessment and Restoration Florida Department of Environmental Protection July 2016 2600 Blair Stone Road Mail Station 3575 Tallahassee, FL 32399-2400 FINAL TMDL Report: Springs Coast Basin, Magnolia–Aripeka Springs Group, Jenkins Creek Spring, and Wilderness–Mud–Salt Springs Group (WBIDs 1391B, 1389, and 1382G), Nutrients, July 2016 Acknowledgments This analysis could not have been accomplished without significant contributions from Kirstin Eller, Edgar Wade, Gary Maddox, and Brian Katz in the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) Water Quality Evaluation and Total Maximum Daily Loads Program, Ground Water Management Section. Hernando Environmental Land Protectors (HELP), Gulf Coast Conservancy, Hernando County Groundwater Guardian, and Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD) provided local and historical studies, including photographs. The authors also appreciate the assistance provided by the SWFWMD in in their review of this report. Map production was provided by Ron Hughes in the DEP Office of Watershed Services. Editorial assistance was provided by Linda -

Nature's Place to Play

PLAN YOUR ADVENTURE TODAY Nature’s Place To Play 800.601.4580 v 352.754.4405 FloridasAdventureCoast.com A B C D E F G H I J K Gulf 98 89 CITY HALL GOVERNMENT CENTER 125 19 PONCE DELEON BLVD. 352.540.3810 352.754.4000 of Mexico HOWELL AVE. LEMON ST. LEMON FORT DADE AVE. 107 MUSEUM CT. S U W. JEFFERSON ST. W. JEFFERSON ST. 24 12 1 N 491 50A 115 127 BROAD ST. C 41 THRASHER AVE. O 109 LIBERTY ST. Y 16 15 200 A A 439 13 41 BROOKSVILLE AVE. S CHASSAHOWITZKA W 110 T 129 K 28 195 R 43 T Wildlife Management Area E. JEFFERSON ST. A R P A & National Wildlife Refuge AVE. SAXON T 99 120 50A I 476 S LAMAR AVE. 165 BROAD ST. L PONCE DE LEON BLVD. ST. LEMON KNUCKEY RD. A SNOW MEMORIAL HWY LAKE LINDSEY RD. EARLY ST. O ST. MAIN C LAKE LINDSEY RD. N 41 476 98 U 38 68 26 GOOD NEIGHBOR TRAILHEAD DALY RD. W COMMERCIAL WAY S 17 147 98 I T LELANI DR. 541 2 LAKE LINDSEY RD. 220 WILLOW ST. H 97 476 L A 69 476 TOLL NOBLETON-CROOM RD. CITY OF BROOKSVILLE CENTRALIA RD. CROOM C 106 O 56 BROOKSVILLE O TRACT C 589 H 105 E E BROAD STREET N. S T A 70 19 T 49 CROOM RD. E S DEMPSEY RD. DEMPSEY 131 T U 193 480 R HEXAM RD. N 74 A 122 Y C I L PINE A 98 50 O 227 100 W 59 A K WITHLACOOCHEE 3 S WAY CITRUS ISLAND R WEEKI T 42 A 73 STATE FOREST COBB RD. -

Lieux D'intérêt Pour Le Centre De La Floride

Lieux d’intérêt pour le centre de la Floride Les attractions d’une valeur remarquable signalées par un diamant | figurent au début de chaque catégorie. ACHATS ET BOÎTES DE NUIT International Drive..........................................................Orlando 49er Flea Market ........................................................ Clearwater International Plaza and Bay Street ..................................Tampa Adjectives Market .........................................Altamonte Springs Ivanhoe Row ..................................................................Orlando Altamonte Mall ..............................................Altamonte Springs The Jacksonville Landing .......................................Jacksonville Altamonte Mall ...............................................................Orlando Jake’s American Bar ......................................................Orlando Amalie Arena ...................................................................Tampa John’s Pass Village & Boardwalk ....................... Madeira Beach Antique Galleries of St. Petersburg .................... St. Petersburg Kathmandu ....................................................................Orlando Artegon Marketplace Orlando .......................................Orlando Kathmandu/Tribalasia ....................................................Orlando Atomic Tonic ..................................................................Orlando The Kennedy ...................................................................Tampa Audubon Park -

Phase I Archaeological Survey of Weeki Wachee Springs State Park, Hernando County, Florida

PHASE I ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WEEKI WACHEE SPRINGS STATE PARK, HERNANDO COUNTY, FLORIDA Jason M. O’Donoughue and Kenneth E. Sassaman Technical Report 18 Laboratory of Southeastern Archaeology Department of Anthropology University of Florida PHASE I ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WEEKI WACHEE SPRINGS STATE PARK, HERNANDO COUNTY, FLORIDA Jason M. O’Donoughue Kenneth E. Sassaman Technical Report 18 Laboratory of Southeastern Archaeology Department of Anthropology University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 Florida DEP Order No. A75928 December 2013 © 2013 Department of Anthropology, University of Florida all rights reserved Cover photo of subsurface testing near the Underwater Mermaid Theater at Weeki Wachee Springs State Park, Hernando County, Florida, March 2013. ii MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The Laboratory of Southeastern Archaeology (LSA) of the Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, conducted a Phase I archaeological survey at Weeki Wachee Springs State Park in March and May 2013 to aid the Florida Division of Recreation and Parks (DRP), Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) as they plan infrastructure rehabilitation and redevelopment in the park. This survey was conducted to identify subsurface cultural resources that could be impacted by redevelopment activities and to evaluate their eligibility for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). An additional goal was to document the depth and extent of recent subsurface disturbance in the APE. This research was conducted under Florida DEP Order #A75928 and 1A-32 permit #1213.023. The survey was performed in accordance with Chapter 267 Florida Statutes and all work including background research, field work, artifact analysis and curation, and preparation of this report conformed to Chapter 1A-46, Florida Administrative Code and the Cultural Resource Management Standards and Operation Manual (FDHR 2002).