Conserve O Gram Volume 8 Issue 3: Preservation of Low-Fired Ceramic Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bonefolder: an E-Journal for the Bookbinder and Book Artist Surface Gilding by James Reid-Cunningham

Bexx Caswell’s binding of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman; Illustrations by Jim Spanfeller. Hallmark, 1969. From the 2009 Bind-O-Rama. Volume 6, Number 1, Fall 2009 The Bonefolder: an e-journal for the bookbinder and book artist Surface Gilding By James Reid-Cunningham 28 Figure 1. The House South of North. Calfskin, gold leaf, Figure 2. Transfer leaf. palladium leaf, kidskin, fish skin, goatskin, box calf, abalone. Gilding on large flat surfaces is best done with transfer leaf Bound 2006. (also called patent leaf), which is gold leaf mounted on a piece Traditional binding decoration utilizes gold leaf to create of thin tissue that allows easily handling without wrinkling or discrete highlights, as in gold finishing. What I refer to as breaking the gold leaf. Transfer leaf can be cut with a scissors. “surface gilding” covers a binding with gold leaf over large Use a scissors reserved only for this task because any scratch areas, even over entire boards. This kind of decoration is rare or little bit of adhesive on the blade will pull the leaf and in bookbinding history, but can be seen in Art Deco bindings break it. When using loose gold leaf, it is necessary to adhere done in France during the 1920s and 1930s. Surface gilding the leaf to the substrate using oil or Vaseline. has become increasingly common among design binders in It sometimes seems that any adhesive ever invented recent years. Whether bound in leather, paper or vellum, has been used at one point or another to adhere gold to a surface gilding gives a spectacularly luxurious effect to a book, so there are many choices of what to use. -

Or on the ETHICS of GILDING CONSERVATION by Elisabeth Cornu, Assoc

SHOULD CONSERVATORS REGILD THE LILY? or ON THE ETHICS OF GILDING CONSERVATION by Elisabeth Cornu, Assoc. Conservator, Objects Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Gilt objects, and the process of gilding, have a tremendous appeal in the art community--perhaps not least because gold is a very impressive and shiny currency, and perhaps also because the technique of gilding has largely remained unchanged since Egyptian times. Gilding restorers therefore have enjoyed special respect in the art community because they manage to bring back the shine to old objects and because they continue a very old and valuable craft. As a result there has been a strong temptation among gilding restorers/conservators to preserve the process of gilding rather than the gilt objects them- selves. This is done by regilding, partially or fully, deteriorated gilt surfaces rather than attempting to preserve as much of the original surface as possible. Such practice may be appropriate in some cases, but it always presupposes a great amount of historic knowledge of the gilding technique used with each object, including such details as the thickness of gesso layers, the strength of the gesso, the type of bole, the tint and karatage of gold leaf, and the type of distressing or glaze used. To illustrate this point, I am asking you to exercise some of the imagination for which museum conservators are so famous for, and to visualize some historic objects which I will list and discuss. This will save me much time in showing slides or photographs. Gilt wooden objects in museums can be broken down into several subcategories: 1) Polychromed and gilt sculptures, altars Examples: baroque church altars, often with polychromed sculptures, some of which are entirely gilt. -

Gilding with Kolner Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay by Lauren Sepp

Gilding with Kolner Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay By Lauren Sepp ’ve been asked many times by custom framing re- achieve different shades. The white Burnishing Clay tailers if there is an easier way to water gild and can be tinted with Mixol tinting agents up to 5 percent I burnish a surface, as it’s generally agreed upon that by weight to achieve any color you desire. traditional water gilding is a labor-intensive method. Both the Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay can be Kolner products address that demand by streamlining applied to many different surfaces. Certain nonpo- the water gilding process, which would otherwise in- rous substrates require no sealing before application clude many more steps. of the clay: Plexiglas and other plastics, sealed woods, Kolner Products, based in Germany, formulated a nonporous paints, and lacquered metals. Unsealed water-based, single-layer, burnishable gilders’ clay for metals may require a primer. Smooth plastics and water gilding in 1985 called Kolner Burnishing Clay. metals may require a light sanding to promote good This product combines and replaces the glue size, ges- adhesion. Porous surfaces such as matboard, paper, so, and bole layers with a single product. The clay is parchment, raw wood, textiles, unglazed ceramics, premixed with an acrylic binder and only needs to be stone, plaster, traditional gesso and compo orna- thinned slightly and stirred. There is no heating, dis- ments require a sealer before applying the clays. In solving of glues, or straining. There is also a sprayable many applications, shellac is a good all-around sealer. -

Gilding Through the Ages

Gilding Through the Ages AN OUTLINE HISTORY OF THE PROCESS IN THE OLD WORLD Andrew Oddy Research Laboratory, The British Museum, London, U.K. In 1845, Sir Edward Thomason wrote in his not public concern but technological advance which memoirs (1) a description of a visit he had made in brought an end to the use of amalgam for gilding. to certain artisans in Paris and he commented: 1814 Gilding with Gold Foil `I was surprised, however, at their secret of superior Although fire-gilding had been in widespread use in gilding of the time-pieces. I was admitted into one gilding establishment, and I found the medium was Europe and Asia for at least 1 500 years when it was similar to ours, mercury; nevertheless the French did displaced by electroplating, the origins of gilding — gild the large ornaments and figures of the chimney- that is, the application of a layer of gold to the surface piece clocks with one-half the gold we could at of a less rare metal — go back at least 5 000 years, to Birmingham, and produced a more even and finer the beginning of the third millennium B.C. The colour'. British Museum has some silver nails from the site of Much to his disgust, Thomason could not persuade Tell Brak in Northern Syria (5) which have had their the French workmen to tell him the secret of their heads gilded by wrapping gold foil over the silver. superior technique, but it seems most likely that it This is, in fact, the earliest form of gilding and it lay either in the preparation of the metal surface depends not on a physical or chemical bond between for gilding or perhaps in the final cleaning and the gold foil and the substrate, but merely on the burnishing of the gilded surface. -

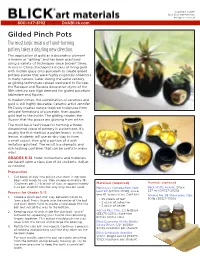

Gilded Pinch Pots the Most Basic Means of Hand-Forming Pottery Takes a Dazzling New Direction

Copyright © 2018 Dick Blick Art Materials All rights reserved 800-447-8192 DickBlick.com Gilded Pinch Pots The most basic means of hand-forming pottery takes a dazzling new direction. The application of gold as a decorative element is known as "gilding" and has been practiced using a variety of techniques since ancient times. Artists in China developed a means of firing gold with molten glass onto porcelain to create gilded pottery pieces that were highly prized by collectors in many nations. Later during the same century, as gilding techniques spread westward to Europe, the Baroque and Rococo decorative styles of the 18th century saw high demand for gilded porcelain tableware and figures. In modern times, the combination of ceramics and gold is still highly desirable. Ceramic artist Jennifer McCurdy creates nature-inspired sculptures from delicate formations of porcelain, then applies gold leaf to the inside. The gilding creates the illusion that the pieces are glowing from within. The most basic technique for forming a three- dimensional piece of pottery is a pinch pot. It's usually the first method a potter learns. In this lesson, students will use air-dry clay to form a small vessel, then gild a portion of it with imitation gold leaf. The result is a dramatic and rich-looking container that can be useful in many ways. GRADES K-12 Note: Instructions and materials are based upon a class size of 24 students. Adjust as needed. Preparation 1. Cut block of clay into pieces and store in zip-lock bags until ready to use. -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. -

GILDING-TECHNIQUES.Pdf

1 GILDING TECHNIQUES A description of various techniques by Aidan Hart THE SYMBOLISM OF GOLD In Orthodox icons, as in sacred arts of many other religions, gold symbolizes divine presence, glory, spiritual light. Gold is not a colour as such, as are the other elements of the icon; it is of a different order of existence. That is, it represents the divine order, which creates and sustains the created order. This being the case the role of gold is not mere decoration. One sign of decadence in the majority of eigtheenth and nineteenth century Russian icons is that gold’s symbolic role was compromised; overly fine gold lines are used as mere ornament, especially on garments. The main places gold is used on traditional icons is the “background”, for haloes, and as gold lines (called assist ) on garments, trees and more rarely, on architectural details. As background the gold shows that it is in God that we “live and move and have our being”, as Saint Paul said. God is like the water within which all creation swims like fish in the ocean. The gold halo represents the Holy Spirit’s indwelling of the saint, the shekena glory of God shining from within. When used as assist the gold represents the material world being transfigured by God. The lines thus do not denote superficial decoration, but rather an inner, transforming presence of the Divine within the inimate world. These lines follow the basic form of the object on which they are drawn - the drapery, tree trunk or whatever - but are abstracted enough to show that they represent a spiritual reality and do not just suggest form. -

GILDING with KOLNER INSTACOLL Ally Burnished Gold

There is a gilding size that many gilders have 3. Apply activator when the Instacoll has dried. not heard of. It was developed by Kolner in It can be applied up to 1 year later. Use a syn- 1990 for interior and exterior gilding projects. thetic fiber brush or a lint free cloth soaked It is called Instacoll and it achieves a super with activator. Apply a thin coat of activator shiny, mirror gloss finish as bright as tradition- on an area that can be gilded within 60 min- GILDING WITH KOLNER INSTACOLL ally burnished gold. Instacoll has been fully utes. Wait until the activator has dried, about tested since 1990 and meets the requirements 15 minutes. Instacoll’s tack is so faint and dry for long lasting exterior gilding. Instacoll was that you really can’t feel it. So it’s best to rely used on the 2583 sq.ft. Victory Column in on the clock. Do not touch the activated area Berlin in 2010.The Berlin State Heritage De- as this will decrease the leaf adhesion. The ac- By Lauren Sepp partment decided to use Instacoll because of tivator is clear, so make sure you have coated the durability it has shown for the last 27 years the whole area you want to gild. In the world of gilding, the question that arises frequent- on exterior gilded projects. It has recently been ly is “can I oil gild a surface and get the look of burnished used on the Academy of the arts in Dresden gold without water gilding.” The answer has always been as well. -

The Gilding Arts Newsletter

The Gilding Arts Newsletter ...an educational resource for Gold Leaf Gilding CHARLES DOUGLAS GILDING STUDIO Seattle, WA Quick Links April 12, 2020 Quick Links Letter from the Gilding Desk: A Gilder's Journal (Blog) Greetings, Class Updates and COVID-19 Georgian Bay Art Conservation Dear Newsletter Friends, Gilding Studio...on Twitter Uffizi Gallery Galleria dell'Accademia di Firenze It goes without saying (although Frye Art Museum I'll say it anyway!) that it's been an unusual and somewhat crazy year Seattle Art Museum with many aspects of our lives turned a bit upside down through Society of Gilders our collective experience of COVID -19. I do hope you are all Metropolitan Museum remaining healthy and heartfelt of Art thoughts to those whose lives have been more impacted than perhaps some of us. Classes which The Fricke Collection have long been scheduled have been postponed and Palace of Versailles remain in a holding pattern. The border with Canada remains closed with quarantines affecting Owen Museo Thyssen- Sound and NY classes for traveling from Seattle Bornemisza with close-knit classes still too difficult or safe to do.We are keeping our eye on developments that Sepp Leaf Products will tell us when more definite dates can be announced while keeping everyone's safety and well-being in the forefront. Gilded Planet Some good news, however, is that a series of Online Gilding Classes through Zoom have been in Join our list development these past few months with Registration now being open for the Fall! Due to the desire to provide gilding assistance to current students-in-waiting as well as helping to meet the growing demand Internationally for gilding education through an Online option it seemed like now was the time. -

Antique Mahogany Ormolu Bijouterie Display Cabinet 19Th C

anticSwiss 01/10/2021 02:05:58 http://www.anticswiss.com Antique Mahogany Ormolu Bijouterie Display Cabinet 19th C FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 19° secolo - 1800 Regent Antiques London Style: Altri stili +44 2088099605 447836294074 Height:102cm Width:55cm Depth:38cm Price:3900€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: This is a beautiful antique French ormolu mounted mahogany bijouterie cabinet, circa 1880 in date. The oval top has a bevelled glass insert over a convex glazed cupboard door which opens to a fitted interior with a single glazed shelf. The cabinet is freestanding, the sides are all glazed and it is raised on elegant tapered cabriole legs decorated with foliate ormolu cast mounts. Complete with working lock and key. Condition: In excellent condition having been beautifully cleaned and waxed in our workshops, please see photos for confirmation. Dimensions in cm: Height 102 x Width 55 x Depth 38 Dimensions in inches: Height 40.2 x Width 21.7 x Depth 15.0 Ormolu - (from French 'or moulu', signifying ground or pounded gold) is an 18th-century English term for applying finely ground, high-carat gold in a mercury amalgam to an object of bronze.The mercury is driven off in a kiln leaving behind a gold-coloured veneer known as 'gilt bronze'. The manufacture of true ormolu employs a process known as mercury-gilding or fire- gilding, in which a solution of nitrate of mercury is applied to a piece of copper, brass, or bronze, followed by the application of an amalgam of gold and mercury. The item was 1 / 3 anticSwiss 01/10/2021 02:05:58 http://www.anticswiss.com then exposed to extreme heat until the mercury burned off and the gold remained, adhered to the metal object. -

Foil and Leaf Gilding on Cultural Artifacts; Forming and Adhesion E

Revista Matéria, v. 16, n. 1, pp. 540 –559, 2011 ISSN 1517-7076 http://www.materia.coppe.ufrj.br/sarra/artigos/artigo11439 Foil and leaf gilding on cultural artifacts; forming and adhesion E. Darque-Ceretti I, Eric Felder I, Marc Aucouturier II I MINES Paristech-CEMEF, Centre de Mise en Forme des Matériaux, CNRS UMR 7635, BP 207, F-06904 Sophia-Antipolis, France. e-mails: [email protected] ; [email protected] II Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, CNRS UMR 171, Palais du Louvre, porte des Lions, 14 quai François Mitterrand, F-75001 Paris France. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The process used to obtain foils of more and more thin thickness and coat them on artefacts varied during centuries. It started from thick foils of the first ages mechanically assembled and evolved until the rolled and beaten leaves, a few hundred nanometres thick. This paper will develop, through examples taken from laboratory studies on museum objects, the main evolution steps of gold leaf forming. It will discuss the present knowledge about processes used by hand-workers of different origins and periods: antic Egypt, Roman Empire, western and oriental Middle-Age, South America, modern Europe. A recent mechanical modelling work about gold forming by beating will be exposed. Then will be described, still through recent examples, some of the non-destructive and destructive laboratory methods used to characterise ancient and modern gildings, their composition, thickness and adhesion modes. The different coating process will be discussed, owing to the presently available knowledge. -

Techniques for Emulating Textiles: Gold and Its Alternatives

Samuel H. Kress Reconstruction Project TECHNIQUES FOR EMULATING TEXTILES: GOLD AND ITS ALTERNATIVES Lesson Plan 16-Adult From left to right: Giotto, Madonna and Child, tempera and gold on panel, ca. 1320-1330 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC); Taddeo di Bartolo, Madonna and Child, tempera and gold on panel, 1410 (Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa). Summary Throughout the ages, artists have come up with a variety of techniques to emulate the elaborate designs and embellishments found on textiles worn by religious and civic figures of great importance. These costly fabrics often incorporated gold threads and designs. Painters often used gold leaf or simulated gold threads found on expensive fabrics with illusionistic painting techniques. Examples of the use of gold leaf can be found in Giotto’s Madonna and Child, The Creation of Eve by Maestro Bartolomé, and Madonna and Child by Taddeo di Bartolo. In this lesson participants will learn to recreate these textiles using mordant gilding and sgraffito. These techniques will also be contrasted with approaches used by northern oil painters of the 15th and 16th centuries. Samuel H. Kress Reconstruction Project Age group: 16 to adult. Length of lesson: 3 lessons (300 minutes total). Objectives: • Introduce the students to the Kress Collection. • Deepen the student’s understanding of how Old Masters emulated textiles. • Enable creative exploration and discovery. Materials: • A projector. • A screen. • Black chalk or 4B pencils for each participant. • A metal stylus for each participant. • Two 8x8 in. prepared wooden panels (purchased with ground already applied) for each student. See the section on ground preparation on this website if you wish to prepare the ground yourself.