Liability of Online Platforms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents This report covers 238 international channels/networks across 152 major operators in 34 EMEA countries. From the total, 67 channels (28%) transmit in high definition (HD). The report shows the reader which international channels are carried by which operator – and which tier or package the channel appears on. The report allows for easy comparison between operators, revealing the gaps and showing the different tiers on different operators that a channel appears on. Published in September 2012, this 168-page electronically-delivered report comes in two parts: A 128-page PDF giving an executive summary, comparison tables and country-by-country detail. A 40-page excel workbook allowing you to manipulate the data between countries and by channel. Countries and operators covered: Country Operator Albania Digitalb DTT; Digitalb Satellite; Tring TV DTT; Tring TV Satellite Austria A1/Telekom Austria; Austriasat; Liwest; Salzburg; UPC; Sky Belgium Belgacom; Numericable; Telenet; VOO; Telesat; TV Vlaanderen Bulgaria Blizoo; Bulsatcom; Satellite BG; Vivacom Croatia Bnet Cable; Bnet Satellite Total TV; Digi TV; Max TV/T-HT Czech Rep CS Link; Digi TV; freeSAT (formerly UPC Direct); O2; Skylink; UPC Cable Denmark Boxer; Canal Digital; Stofa; TDC; Viasat; You See Estonia Elion nutitv; Starman; ZUUMtv; Viasat Finland Canal Digital; DNA Welho; Elisa; Plus TV; Sonera; Viasat Satellite France Bouygues Telecom; CanalSat; Numericable; Orange DSL & fiber; SFR; TNT Sat Germany Deutsche Telekom; HD+; Kabel -

Rp. 149.000,- Rp

Indovision Basic Packages SUPER GALAXY GALAXY VENUS MARS Rp. 249.000,- Rp. 179.000,- Rp. 149.000,- Rp. 149.000,- Animax Animax Animax Animax AXN AXN AXN AXN BeTV BeTV BeTV BeTV Channel 8i Channel 8i Channel 8i Channel 8i E! Entertainment E! Entertainment E! Entertainment E! Entertainment FOX FOX FOX FOX FOXCrime FOXCrime FOXCrime FOXCrime FX FX FX FX Kix Kix Kix Kix MNC Comedy MNC Comedy MNC Comedy MNC Comedy MNC Entertainment MNC Entertainment MNC Entertainment MNC Entertainment One Channel One Channel One Channel One Channel Sony Entertainment Television Sony Entertainment Television Sony Entertainment Television Sony Entertainment Television STAR World STAR World STAR World STAR World Syfy Universal Syfy Universal Syfy Universal Syfy Universal Thrill Thrill Thrill Thrill Universal Channel Universal Channel Universal Channel Universal Channel WarnerTV WarnerTV WarnerTV WarnerTV Al Jazeera English Al Jazeera English Al Jazeera English Al Jazeera English BBC World News BBC World News BBC World News BBC World News Bloomberg Bloomberg Bloomberg Bloomberg Channel NewsAsia Channel NewsAsia Channel NewsAsia Channel NewsAsia CNBC Asia CNBC Asia CNBC Asia CNBC Asia CNN International CNN International CNN International CNN International Euronews Euronews Euronews Euronews Fox News Fox News Fox News Fox News MNC Business MNC Business MNC Business MNC Business MNC News MNC News MNC News MNC News Russia Today Russia Today Russia Today Russia Today Sky News Sky News Sky News Sky News BabyTV BabyTV BabyTV BabyTV Boomerang Boomerang Boomerang Boomerang -

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS with SUNRISE TV TV Channel List for Printing

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS WITH SUNRISE TV TV channel list for printing Need assistance? Hotline Mon.- Fri., 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. Sat. - Sun. 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. 0800 707 707 Hotline from abroad (free with Sunrise Mobile) +41 58 777 01 01 Sunrise Shops Sunrise Shops Sunrise Communications AG Thurgauerstrasse 101B / PO box 8050 Zürich 03 | 2021 Last updated English Welcome to Sunrise TV This overview will help you find your favourite channels quickly and easily. The table of contents on page 4 of this PDF document shows you which pages of the document are relevant to you – depending on which of the Sunrise TV packages (TV start, TV comfort, and TV neo) and which additional premium packages you have subscribed to. You can click in the table of contents to go to the pages with the desired station lists – sorted by station name or alphabetically – or you can print off the pages that are relevant to you. 2 How to print off these instructions Key If you have opened this PDF document with Adobe Acrobat: Comeback TV lets you watch TV shows up to seven days after they were broadcast (30 hours with TV start). ComeBack TV also enables Go to Acrobat Reader’s symbol list and click on the menu you to restart, pause, fast forward, and rewind programmes. commands “File > Print”. If you have opened the PDF document through your HD is short for High Definition and denotes high-resolution TV and Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari...): video. Go to the symbol list or to the top of the window (varies by browser) and click on the print icon or the menu commands Get the new Sunrise TV app and have Sunrise TV by your side at all “File > Print” respectively. -

European” News

Producing ”European” News. The Case of the Pan-European News Channel Euronews Olivier Baisnée, Dominique Marchetti To cite this version: Olivier Baisnée, Dominique Marchetti. Producing ”European” News. The Case of the Pan-European News Channel Euronews. 2010, pp.1-32. halshs-00665816 HAL Id: halshs-00665816 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00665816 Submitted on 2 Feb 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Working Paper Series e 2010/I Meenakshi Thapan and Maitrayee Deka : South Asian Migrants in Europe : Heterogeneity, Multiplicity and the Overcoming of Difference. Producing "European" m 2010/II Eric Fassin : The Sexual Politics of Immigration and National Identities in Contemporary Europe. News m 2010/III Case of the Pan-European Johan Heilbron : Transnational Cultural Exchange and Globalization. a 2011/IV r News Channel Euronews Bertrand Reau : Making a Utopia? An Ethnography of Club Med Resorts in the 1950s. g o r P s e i d Olivier Baisnée Dominique Marchetti u t Translated From The French by : S Chandrika Mathur n a e University of Delhi p Working Paper Series o r 2010/V u (The project is funded by the European Union) www.europeanstudiesgroupdu.org E Working Paper Series 2010/V Working Paper Series 2010/V Translated by: Chandrika Mathur [email protected] Producing "European" News © Olivier Baisnée Case of the Pan-European News Channel Euronews © Dominique Marchetti Olivier Baisnée, is associate professor of political science at the Institute for Political Studies in Toulouse. -

Samsung TV Plus

Samsung TV Plus Channel Descriptions | Italy | 9th Dec 2020 Channel Description Info Samsung Name Logo Genre Summary TV Plus # Welcome to Amuse Animation! All of our content is 100% safe for children. Together, let's meet our Car City heroes: Amuse Animation Kids & Family 4302 Carl, Tom, Car Parol and many more! New episodes come out every day! In Big Name, discover fascinating biopics that retrace the history of the great names of humanity. (Re) discover the Big Name Entertainment 4251 history of those who have stood out notably for our greatest good ... or our greatest misfortune. Bizzarro Movies Channel will present all those movies that, as the word itself suggests, appear «weird», but which have Bizzarro Movies Movies 4502 made themselves famous all over the world, so much to become real cults for a very huge audience. Bloomberg TV+ UHD delivers Live 24x7 global business and markets news, data, analysis, and stories from Bloomberg Bloomberg TV+ News 4007 News and Businessweek – available in a 4K ultra high definition (UHD) viewing experience. The Brindiamo! Channel provides an informative, educational, yet fun window to everything Italian - from Brindiamo! Lifestyle 4351 travel to food, art, lifestyles, and successful stories, through TV Series, documentaries and short movies. Do you love cinema? This is the channel for you! On CGtv you will find Italian and international cult films, comedies CGtv Movies and genre films as well as critically acclaimed films and a 4504 wide selection of the best documentaries made in recent years. Secret Cinema will cover 30 years of Italian cinema, ranging from classic films directed by great directors and starring Cinema Segreto Movies 4503 great actors to lesser-known but still appreciated films all over the world. -

The New Frontiers of User Rights

American University International Law Review Volume 32 Article 1 Issue 1 Issue1 2016 The ewN Frontiers Of User Rights Niva Elkin-Koren University of Haifa, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Elkin-Koren, Niva (2016) "The eN w Frontiers Of User Rights," American University International Law Review: Vol. 32 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr/vol32/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELKINREVISED.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 10/24/16 3:45 PM ARTICLES THE NEW FRONTIERS OF USER RIGHTS * NIVA ELKIN-KOREN I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................2 II. FAIR USE AND NEW CHALLENGES TO ACCESS TO KNOWLEDGE ..............................................................................5 A. ACCESS TO KNOWLEDGE ............................................................5 B. NEW FRONTIERS IN ACCESS TO KNOWLEDGE ...........................8 C. BARRIERS TO ACCESS AND COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT BY ONLINE INTERMEDIARIES .......................................................13 -

No Monitoring Obligations’ the Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ a Story of Untameable Monsters by Giancarlo F

The Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ The Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ A Story of Untameable Monsters by Giancarlo F. Frosio* Abstract: In imposing a strict liability regime pean Commission, would like to introduce filtering for alleged copyright infringement occurring on You- obligations for intermediaries in both copyright and Tube, Justice Salomão of the Brazilian Superior Tribu- AVMS legislations. Meanwhile, online platforms have nal de Justiça stated that “if Google created an ‘un- already set up miscellaneous filtering schemes on a tameable monster,’ it should be the only one charged voluntary basis. In this paper, I suggest that we are with any disastrous consequences generated by the witnessing the death of “no monitoring obligations,” lack of control of the users of its websites.” In order a well-marked trend in intermediary liability policy to tame the monster, the Brazilian Superior Court that can be contextualized within the emergence of had to impose monitoring obligations on Youtube; a broader move towards private enforcement online this was not an isolated case. Proactive monitoring and intermediaries’ self-intervention. In addition, fil- and filtering found their way into the legal system as tering and monitoring will be dealt almost exclusively a privileged enforcement strategy through legisla- through automatic infringement assessment sys- tion, judicial decisions, and private ordering. In multi- tems. Due process and fundamental guarantees get ple jurisdictions, recent case law has imposed proac- mauled by algorithmic enforcement, which might fi- tive monitoring obligations on intermediaries across nally slay “no monitoring obligations” and fundamen- the entire spectrum of intermediary liability subject tal rights online, together with the untameable mon- matters. -

Digital Millennium Copyright Act

Safe Harbor for Online Service Providers Under Section 512(c) of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act March 26, 2014 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R43436 Safe Harbor for Online Service Providers Under Section 512(c) of the DMCA Summary Congress passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in 1998 in an effort to adapt copyright law to emerging digital technologies that potentially could be used to exponentially increase infringing activities online. Title II of the DMCA, titled the “Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act,” added a new Section 512 to the Copyright Act (Title 17 of the U.S. Code) in order to limit the liability of providers of Internet access and online services that may arise due to their users posting or sharing materials that infringe copyrights. Congress was concerned that without insulating Internet intermediaries from crippling financial liability for copyright infringement, investment in the growth of the Internet could be stifled and innovation could be harmed. The § 512 “safe harbor” immunity is available only to a party that qualifies as a “service provider” as defined by the DMCA, and only after the provider complies with certain eligibility requirements. The DMCA’s safe harbors greatly limit service providers’ liability based on the specific functions they could perform: (1) transitory digital network communications, (2) system caching, (3) storage of information on systems or networks at direction of users, and (4) information location tools. In exchange for the shelter from most forms of liability, the DMCA requires service providers to cooperate with copyright owners to address infringing activities conducted by the providers’ customers. -

TV News Channels in Europe: Offer, Establishment and Ownership European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2018

TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2018 Director of publication Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director Editorial supervision Gilles Fontaine, Head of Department for Market Information Author Laura Ene, Analyst European Television and On-demand Audiovisual Market European Audiovisual Observatory Proofreading Anthony A. Mills Translations Sonja Schmidt, Marco Polo Sarl Press and Public Relations – Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] European Audiovisual Observatory Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76 Allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France Tel.: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 00 Fax. : +33 (0)3 90 21 60 19 [email protected] http://www.obs.coe.int Cover layout – ALTRAN, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France Please quote this publication as Ene L., TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership, European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2018 © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, July 2018 If you wish to reproduce tables or graphs contained in this publication please contact the European Audiovisual Observatory for prior approval. Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership Laura Ene Table of contents 1. Key findings ...................................................................................................................... -

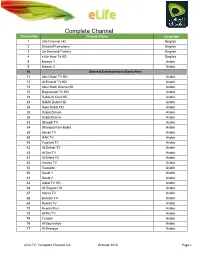

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Dmca Safe Harbors: an Analysis of the Statute and Case Law

DMCA SAFE HARBORS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE STATUTE AND CASE LAW Excerpted from Chapter 4 (Copyright Protection in Cyberspace) from the April 2020 updates to E-Commerce and Internet Law: Legal Treatise with Forms 2d Edition A 5-volume legal treatise by Ian C. Ballon (Thomson/West Publishing, www.IanBallon.net) INTERNET, MOBILE AND DIGITAL LAW YEAR IN REVIEW: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW FOR 2021 AND BEYOND ASSOCIATION OF CORPORATE COUNSEL JANUARY 14, 2021 Ian C. Ballon Greenberg Traurig, LLP Silicon Valley: Los Angeles: 1900 University Avenue, 5th Fl. 1840 Century Park East, Ste. 1900 East Palo Alto, CA 914303 Los Angeles, CA 90067 Direct Dial: (650) 289-7881 Direct Dial: (310) 586-6575 Direct Fax: (650) 462-7881 Direct Fax: (310) 586-0575 [email protected] <www.ianballon.net> LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook: IanBallon This paper has been excerpted from E-Commerce and Internet Law: Treatise with Forms 2d Edition (Thomson West April 2020 Annual Update), a 5-volume legal treatise by Ian C. Ballon, published by West, (888) 728-7677 www.ianballon.net Ian C. Ballon Silicon Valley 1900 University Avenue Shareholder 5th Floor Internet, Intellectual Property & Technology Litigation East Palo Alto, CA 94303 T 650.289.7881 Admitted: California, District of Columbia and Maryland F 650.462.7881 Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Seventh, Ninth, Eleventh and Federal Circuits Los Angeles U.S. Supreme Court 1840 Century Park East JD, LLM, CIPP/US Suite 1900 Los Angeles, CA 90067 [email protected] T 310.586.6575 LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook: IanBallon F 310.586.0575 Ian C. Ballon is Co-Chair of Greenberg Traurig LLP’s Global Intellectual Property & Technology Practice Group and represents companies in intellectual property litigation (including copyright, trademark, trade secret, patent, right of publicity, DMCA, domain name, platform defense, fair use, CDA and database/screen scraping) and in the defense of data privacy, cybersecurity breach and TCPA class action suits. -

Section 512 of Title 17 a Report of the Register of Copyrights May 2020 United States Copyright Office

united states copyright office section 512 of title 17 a report of the register of copyrights may 2020 united states copyright office section 512 of title 17 a report of the register of copyrights may 2020 U.S. Copyright Office Section 512 Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The publication of this Report is the final output of several years of effort by the Copyright Office to assist Congress with evaluating ways to update the Copyright Act for the 21st century. The genesis of this Report occurred in the midst of the two years of copyright review hearings held by the House Judiciary Committee that spanned the 113th and 114th Congresses. At the twentieth and final hearing in April 2015, the Copyright Office proposed several policy studies to aid Congress in its further review of the Copyright Act. Two studies already underway at the time were completed after the hearings: Orphan Works and Mass Digitization (2015), which the Office later supplemented with a letter to Congress on the “Mass Digitization Pilot Program” (2017), and The Making Available Right in the United States (2016). Additional studies proposed during the final hearing that were subsequently issued by the Office included: the discussion document Section 108 of Title 17 (2017), Section 1201 of Title 17 (2017), and Authors, Attribution, and Integrity: Examining Moral Rights in the United States (2019). The Office also evaluated how the current copyright system works for visual artists, which resulted in the letter to Congress titled “Copyright and Visual Works: The Legal Landscape of Opportunities and Challenges” (2019). Shortly after the hearings ended, two Senators requested a review of the role of copyright law in everyday consumer products and the Office subsequently published a report, Software-Enabled Computer Products (2016).