Limhi in the Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events Earl M. Wunderli DURING THE PAST FEW DECADES, a number of LDS scholars have developed various "limited geography" models of where the events of the Book of Mormon occurred. These models contrast with the traditional western hemisphere model, which is still the most familiar to Book of Mormon readers. Of the various models, the only one to have gained a following is that of John Sorenson, now emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University. His model puts all the events of the Book of Mormon essentially into southern Mexico and southern Guatemala with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the "narrow neck" described in the LDS scripture.1 Under this model, the Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites were relatively small colonies living concurrently with other peoples in- habiting the rest of the hemisphere. Scholars have challenged Sorenson's model based on archaeological and other external evidence, but lay people like me are caught in the crossfire between the experts.2 We, however, can examine Sorenson's model based on what the Book of Mormon itself says. One advantage of 1. John L. Sorenson, "Digging into the Book of Mormon," Ensign, September 1984, 26- 37; October 1984, 12-23, reprinted by the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS); An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: De- seret Book Company, and Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1990); "The Book of Mormon as a Mesoameri- can Record," in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. -

L17 a Seer … Becometh a Great Benefit to His Fellow Beings.Pages

Lesson 17: “A Seer … Becometh a Great Benefit to His Fellow Beings” (Mos. 7–11) L17 Study Guide Purpose: To encourage us to follow the counsel of Church leaders, particularly our prophets, seers, and revelators” See the diagram and explanation of the Land of Lehi-Nephi. 1. Ammon and his brethren find Limhi and his people. Ammon teaches Limhi of the importance of a seer. (Mosiah 7-8.) • Mos. 7:7-11 Ammon and his15 cohorts are taken captive by King Limhi’s guards. • Mos. 7:12-15 Ammon tells his story and King Limhi rejoices. • Mos. 7:17-20, 29-33 What principles does King Limhi teach his people? What does this tell us about King Limhi? • Mos. 8:7 King Limhi reports that he had sent out a scouting part of 43 persons to find Zarahemla. • Mos. 8:8-12 They found 24 gold plates and King Limhi desires they be translated. Why would it be helpful for Limhi’s people, and us, to “know the cause of [the] destruction” of the Jaredites? • Mosiah 8:13-16 Ammon told Limhi of a king who was a prophet and seer. • Mosiah 8:13, 17-18 How do prophets, seers, and revelators fulfill these roles? How have latter-day prophets, seers, and revelators been “a great benefit” to you? †1. Elder Boyd K. Packer †2. Elder John A. Widstoe 2. The record of Zeniff recounts a brief history of Zeniff’s people. (Mosiah 9-10.) Chapters 9 through 22 “of the book of Mosiah contain a history of the people who left Zarahemla to return to the land of Nephi. -

Formulas and Faith

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 21 Number 1 Article 6 2012 Formulas and Faith John Gee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gee, John (2012) "Formulas and Faith," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 21 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol21/iss1/6 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Formulas and Faith Author(s) John Gee Reference Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21/1 (2012): 60–65. ISSN 1948-7487 (print), 2167-7565 (online) Abstract The question of where Joseph Smith received the text of the Book of Abraham has elicited three main theories, one of which, held by a minority of church members, is that Joseph translated it from papyri that we no longer have. It is conjectured that if this were the case, then the contents of the Book of Abraham must have been on what nineteenth-century witnesses described as the “long roll.” Two sets of scholars devel- oped mathematical formulas to discover, from the remains of what they believe to be the long roll, what the length of the long roll would have been. However, when these formulas are applied on scrolls of known length, they produce erratic or inconclusive results, thus casting doubt on their ability to accurately con- clude how long the long roll would have been. -

Mosiah the Lack of a Preface for the Book of Mosiah in the Present Book

Book of Mormon Commentary Mosiah 1 Mosiah The lack of a preface for the book of Mosiah in the present Book of Mormon is probably because the text takes 1 up the Mosiah account some time after its original beginning. The original manuscript of the Book of Mormon, written in Oliver Cowdery’s hand, has no title for the Book of Mosiah. It was inked in later, prior to sending it to the printer for typesetting. The first part of Mormon’s abridgment of Mosiah’s record…was evidently on the 116 pages lost by Martin Harris. John A. Tvedtnes, Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, ed. By John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne [Salt Lake City: 1991], 33 Note that the main story in the book of Mosiah is told in the third person rather than in the first person as was the 2 custom in the earlier books of the Book of Mormon. The reason for this is that someone else is now telling the story and that “someone else” is Mormon. With the beginning of the book of Mosiah we start our study of Mormon’s abridgment of various books that had been written on the large plates of Nephi (3 Nephi 5:8-12). The book of Mosiah and the five books that follow—Alma, Helaman, 3 Nephi, 4 Nephi, and Mormon—were all abridged or condensed by Mormon from the large plates of Nephi, and these abridged versions were written by Mormon on the plates that bear his name, the plates of Mormon. These are the same plates that were given to Joseph Smith by the angel Moroni on September 22, 1827. -

“They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton's Dissent

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2020-8 “They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton’s Dissent Dan Belnap Brigham Young University, [email protected] Daniel L. Belnap Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Belnap, Dan and Belnap, Daniel L., "“They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton’s Dissent" (2020). Faculty Publications. 4479. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/4479 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ILLUMINATING THE RECORDS Edited by Daniel L. Belnap Published by the Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, in cooper- ation with Deseret Book Company, Salt Lake City. Visit us at rsc.byu.edu. © 2020 by Brigham Young University. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Inc. DESERET BOOK is a registered trademark of Deseret Book Company. Visit us at DeseretBook.com. Any uses of this material beyond those allowed by the exemptions in US copyright law, such as section 107, “Fair Use,” and section 108, “Library Copying,” require the written permission of the publisher, Religious Studies Center, 185 HGB, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of Brigham Young University or the Religious Studies Center. -

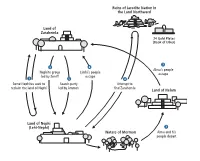

Land of Zarahemla Land of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) Waters of Mormon

APPENDIX Overview of Journeys in Mosiah 7–24 1 Some Nephites seek to reclaim the land of Nephi. 4 Attempt to fi nd Zarahemla: Limhi sends a group to fi nd They fi ght amongst themselves, and the survivors return to Zarahemla and get help. The group discovers the ruins of Zarahemla. Zeniff is a part of this group. (See Omni 1:27–28 ; a destroyed nation and 24 gold plates. (See Mosiah 8:7–9 ; Mosiah 9:1–2 .) 21:25–27 .) 2 Nephite group led by Zeniff settles among the Lamanites 5 Search party led by Ammon journeys from Zarahemla to in the land of Nephi (see Omni 1:29–30 ; Mosiah 9:3–5 ). fi nd the descendants of those who had gone to the land of Nephi (see Mosiah 7:1–6 ; 21:22–24 ). After Zeniff died, his son Noah reigned in wickedness. Abinadi warned the people to repent. Alma obeyed Abinadi’s message 6 Limhi’s people escape from bondage and are led by Ammon and taught it to others near the Waters of Mormon. (See back to Zarahemla (see Mosiah 22:10–13 ). Mosiah 11–18 .) The Lamanites sent an army after Limhi and his people. After 3 Alma and his people depart from King Noah and travel becoming lost in the wilderness, the army discovered Alma to the land of Helam (see Mosiah 18:4–5, 32–35 ; 23:1–5, and his people in the land of Helam. The Lamanites brought 19–20 ). them into bondage. (See Mosiah 22–24 .) The Lamanites attacked Noah’s people in the land of Nephi. -

Conversion of Alma the Younger

Conversion of Alma the Younger Mosiah 27 I was in the darkest abyss; but now I behold the marvelous light of God. Mosiah 27:29 he first Alma mentioned in the Book of Mormon Before the angel left, he told Alma to remember was a priest of wicked King Noah who later the power of God and to quit trying to destroy the Tbecame a prophet and leader of the Church in Church (see Mosiah 27:16). Zarahemla after hearing the words of Abinadi. Many Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah fell people believed his words and were baptized. But the to the earth. They knew that the angel was sent four sons of King Mosiah and the son of the prophet from God and that the power of God had caused the Alma, who was also called Alma, were unbelievers; ground to shake and tremble. Alma’s astonishment they persecuted those who believed in Christ and was so great that he could not speak, and he was so tried to destroy the Church through false teachings. weak that he could not move even his hands. The Many Church members were deceived by these sons of Mosiah carried him to his father. (See Mosiah teachings and led to sin because of the wickedness of 27:18–19.) Alma the Younger. (See Mosiah 27:1–10.) When Alma the Elder saw his son, he rejoiced As Alma and the sons of Mosiah continued to rebel because he knew what the Lord had done for him. against God, an angel of the Lord appeared to them, Alma and the other Church leaders fasted and speaking to them with a voice as loud as thunder, prayed for Alma the Younger. -

Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham You from Me.”2 the Same Principle Can Be Applied to the Book of Abraham

Book of Abraham Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham you from me.”2 The same principle can be applied to the book of Abraham. The Lord did not require Joseph The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints em- Smith to have knowledge of Egyptian. By the gift and braces the book of Abraham as scripture. This book, a power of God, Joseph received knowledge about the life record of the biblical prophet and patriarch Abraham, and teachings of Abraham. recounts how Abraham sought the blessings of the On many particulars, the book of Abraham is con- priesthood, rejected the idolatry of his father, covenant- sistent with historical knowledge about the ancient ed with Jehovah, married Sarai, moved to Canaan and world.3 Some of this knowledge, which is discussed lat- Egypt, and received knowledge about the Creation. The er in this essay, had not yet been discovered or was not book of Abraham largely follows the biblical narrative well known in 1842. But even this evidence of ancient but adds important information regarding Abraham’s origins, substantial though it may be, cannot prove the life and teachings. truthfulness of the book of Abraham any more than ar- The book of Abraham was first published in 1842 chaeological evidence can prove the exodus of the Isra- and was canonized as part of the Pearl of Great Price in elites from Egypt or the Resurrection of the Son of God. 1880. The book originated with Egyptian papyri that Jo- The book of Abraham’s status as scripture ultimately seph Smith translated beginning in 1835. -

May 18 – 24 Mosiah 25 – 28 “They Were Called the People of God”

Come, Follow Me: May 18 – 24 Mosiah 25 – 28 “They Were Called the People of God” We now have a coming together of all the Israelites in the New World, except for the rebellious Lamanites. The Mulekites of Zarahemla had been discovered by Mosiah (the first) and desired that he should rule over them. Zeniff had departed back to the Land of Nephi and his descendants had been oppressed by the Lamanites. God had delivered them, and they had arrived in Zarahemla. Alma (the Elder) had been a priest of the wicked King Noah (Zeniff’s son) who had been converted by the words of Abinadi. He had fled to the waters of Mormon and baptized about 400 people there. They had fled King Noah and established a city, which was overrun by Lamanites. After being persecuted, they were also delivered by God and had arrived in Zarahemla. What were God’s purposes in gathering these Israelites Figure 1Mosiah II by James Fullmer via (descendants of Judah—the Mulekites—and Joseph—the bookofmormonbattles.com Nephites) in one place? The people of Alma and Limhi in Zarahemla (Mosiah 25): Mosiah (the second, the son of King Benjamin) called all the people together in a great conference in two bodies. The Mulekites outnumbered the Nephites. Why did the Mulekites desire to be taught the language of the Nephites and have them rule? When they had been gathered (verse 5) he had the records of Zeniff’s people read to those who had gathered. All the people had wondered what had become of Zeniff. -

A Third Jaredite Record: the Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 11 Number 1 Article 10 7-31-2002 A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates Valentin Arts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Arts, Valentin (2002) "A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 11 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol11/iss1/10 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates Author(s) Valentin Arts Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 11/1 (2002): 50–59, 110–11. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract In the Book of Mormon, two records (a large engraved stone and twenty-four gold plates) contain the story of an ancient civilization known as the Jaredites. There appears to be evidence of an unpublished third record that provides more information on this people and on the history of the world. When the brother of Jared received a vision of Jesus Christ, he was taught many things but was instructed not to share them with the world until the time of his death. The author proposes that the brother of Jared did, in fact, write those things down shortly before his death and then buried them, along with the interpreting stones, to be revealed to the world according to the timing of the Lord. -

The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 6 Number 2 Article 18 7-31-1997 The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi David E. Sloan Van Cott, Bagley and Cornwall, Salt Lake City Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sloan, David E. (1997) "The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 6 : No. 2 , Article 18. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol6/iss2/18 This Notes and Communications is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Notes and Communications: The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi Author(s) David E. Sloan Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 6/2 (1997): 269–72. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon consistently use such phrases as “Book of Lehi,” “plates of Lehi,” and “account of Nephi” in distinct ways. NOTES AND COMMUNICATIONS The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi David E. Sloan In the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith wrote that the lost 116 pages included his translation of "the Book of Lehi, which was an account abridged from the plates of Lehi, by the hand of Mormon." However, in Doctrine and Covenants 10:44, the Lord told Joseph that the lost pages contained "an abridgment of the account of Nephi." Some critics have argued that these statements are contradictory and therefore somehow provide evidence that Joseph Smith was not a prophet. -

B. a Chronological List of English Reader-Friendly Sources on Hebrew-Like Literary Language and Structures That Relate to the Book of Mormon

B. A Chronological List of English Reader-Friendly Sources on Hebrew-like Literary Language and Structures That Relate to the Book of Mormon In the chronological listing of articles and books, the following system of identification will be used: Year = after 1830, non-LDS scholarly Year = after 1830, LDS Year^ = anti-Mormon 1829-30 Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon As Joseph dictated, Oliver Cowdery and other scribes wrote the dictation on folded foolscap paper (6 5/8 x 16 ½), line-after-line without significant punctuation, capitalization or paragraphs. Roughly 25 per cent of the Original Manuscript survives. Original Manuscript lightplanet.com 205 (Sources: 1830→ Present) (Sources Shirley R. Heater, “History of the Manuscripts of the Book of Mormon.” In Recent Book of Mormon Developments, vol. 2, 1992: 80-88) 1830 Printer’s Manuscript of the Book of Mormon In preparation for printing, Joseph had Oliver copy the Original Manuscript into what is called the “Printer’s Manuscript.” According to Royal Skousen, the Printers Manuscript is not an exact copy of the Original Manuscript. Skousen found on the average three changes per Original Manuscript page. In Skousen’s view, “these changes appear to be natural scribal errors; there is little or no evidence of conscious editing. Most of the changes were minor, and about one in five produced a discernible difference in meaning.” The Printers Manuscript has wholly survived except for two lines. (Source: Royal Skousen, “Manuscripts of the Book of Mormon.” In To All the World: The Book of Mormon Articles from the Encyclopedia of Mormonism, p. 179) Printers Manuscript stepbystep 1830 1830 Edition of The Book of Mormon (Palmyra) Working for owner E.B.