Duwamish Resolution Briefing Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North: Lummi, Nooksack, Samish, Sauk-Suiattle, Stillaguamish

Policy 7.01 Implementation Plan Region 2 North (R2N) Community Services Division (CSD) Serving the following Tribes: Lummi Nation, Nooksack Indian Tribe, Samish Indian Nation, Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians, Swinomish Tribal Community, Tulalip Tribes, & Upper Skagit Indian Tribe Biennium Timeframe: July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022 Revised 04/2021 Annual Key Due Dates: April 1st - CSD Regional Administrators submit 7.01 Plan and Progress Reports (PPRs) to CSD HQ Coordinator. April 13th – CSD HQ Coordinator will submit Executive Summary & 7.01 PPRs to the ESA Office of Assistant Secretary for final review. April 23rd - ESA Office of the Assistant Secretary will send all 7.01 PPRs to Office of Indian Policy (OIP). 7.01 Meetings: January 17th- Cancelled due to inclement weather Next scheduled meeting April 17th, hosted by the Nooksack Indian Tribe. 07/07/20 Virtual 7.01 meeting. 10/16/20 7.01 Virtual meeting 01/15/21 7.01 Virtual 04/16/21 7.01 Virtual 07/16/21 7.01 Virtual Implementation Plan Progress Report Status Update for the Fiscal Year Goals/Objectives Activities Expected Outcome Lead Staff and Target Date Starting Last July 1 Revised 04/2021 Page 1 of 27 1. Work with tribes Lead Staff: to develop Denise Kelly 08/16/2019 North 7.01 Meeting hosted by services, local [email protected] , Tulalip Tribes agreements, and DSHS/CSD Tribal Liaison Memorandums of 10/18/2019 North 7.01 Meeting hosted by Understanding Dan Story, DSHS- Everett (MOUs) that best [email protected] meet the needs of Community Relations 01/17/2020 North 7.01 Meeting Region 2’s Administrator/CSD/ESA scheduled to be hosted by Upper Skagit American Indians. -

Hylebos Watershed Plan

Hylebos Watershed Plan July 2016 EarthCorps 6310 NE 74th Street, Suite 201E Seattle, WA 98115 Prepared by: Matt Schwartz, Project Manager Nelson Salisbury, Ecologist William Brosseau, Operations Director Pipo Bui, Director of Foundation and Corporate Relations Rob Anderson, Senior Project Manager Acknowledgements Support for the Hylebos Watershed Plan is provided by the Puget Sound Stewardship and Mitigation Fund, a grantmaking fund created by the Puget Soundkeeper Alliance and administered by the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment. Hylebos Watershed Plan- EarthCorps 2016 | 1 June 28, 2016 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 History of EarthCorps/Friends of the Hylebos ........................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Key Stakeholders ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Purpose of Report- The Why ............................................................................................................................... 7 3 Goals and Process- The What and The How ................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Planning Process .................................................................................................................................................... -

Section II Community Profile

Section II: Community Profile Section II Community Profile Hazard Mitigation Plan 2010 Update 9 [this page intentionally left blank] 10 Hazard Mitigation Plan 2010 Update Section II: Community Profile Community Profile Disclaimer: The Tulalip Tribes Tribal/State Hazard Mitigation Plan covers all the people, property, infrastructure and natural environment within the exterior boundaries of the Tulalip Reservation as established by the Point Elliott Treaty of January 22, 1855 and by Executive Order of December 23, 1873, as well as any property owned by the Tulalip Tribes outside of this area. Furthermore the Plan covers the Tulalip Tribes Usual and Accustom Fishing areas (U&A) as determined by Judge Walter E. Craig in United States of America et. al., plaintiffs v. State of Washington et. al., defendant, Civil 9213 Phase I, Sub Proceeding 80-1, “In Re: Tulalip Tribes’ Request for Determination of Usual and Accustom Fishing Places.” This planning scope does not limit in any way the Tulalip Tribes’ hazard mitigation and emergency management planning concerns or influence. This section will provide detailed information on the history, geography, climate, land use, population and economy of the Tulalip Tribes and its Reservation. Tulalip Reservation History Archaeologists and historians estimate that Native Americans arrived from Siberia via the Bering Sea land bridge beginning 17,000 to 11,000 years ago in a series of migratory waves during the end of the last Ice Age. Indians in the region share a similar cultural heritage based on a life focused on the bays and rivers of Puget Sound. Throughout the Puget Sound region, While seafood was a mainstay of the native diet, cedar trees were the most important building material.there were Cedar numerous was used small to tribesbuild both that subsistedlonghouses on and salmon, large halibut,canoes. -

Duwamish Superfund HIA Tribal Report Final June 2013 Clean

Health Impact Assessment Proposed Cleanup Plan for the Lower Duwamish Waterway Superfund Site Technical Report September, 2013 (Final version) Assessment and Recommendations Effects of the proposed cleanup plan on Tribes Duwamish Superfund HIA – Technical Report: Tribes (Final version; September 2013) Technical report This technical report supports our HIA Final Report, published in September, 2013. This technical report is identical to the version that accompanied our Public Comment HIA Report, which was submitted to EPA on June 13, 2013. Acknowledgment and disclaimer We are indebted to the many agencies, organizations, and individuals who have contributed their time, information, and expertise to this project. This project and report were supported by a grant from the Health Impact Project, a collaboration oF the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts; and also by the Rohm & Haas Professorship in Public Health Sciences, sponsored by the Rohm & Haas Company of Philadelphia. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Health Impact Project, The Pew Charitable Trusts, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, or the Rohm & Haas Company. Health Impact Assessment authors William Daniell University of Washington Linn Gould * Just Health Action BJ Cummings Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition/Technical Advisory Group Jonathan Childers University of Washington Amber Lenhart University of Washington * Primary author(s) for this technical report. Suggested citation Gould L, Cummings BJ, Daniell W, Lenhart A, Childers J. Health Impact Assessment: Proposed Cleanup Plan for the Lower Duwamish Waterway Superfund Site; Technical Report: Effects of the proposed cleanup plan on Tribes. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Just Health Action, and Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition/Technical Advisory Group. -

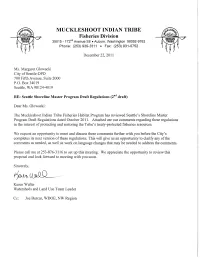

Shoreline Master Program Second Draft Comments

MUCKLESHOOT INDIAN TRIBE Fisheries Division 39015 - 172nd Avenue SE . Auburn, Washington 98092-9763 Phone: (253) 939-3311 . Fax: (253) 931-0752 December 22,2011 Ms. Margaret Glowacki City of Seattle-DPD 700 Fifth Avenue, Suite 2000 P.O. Box 34019 Seattle, WA 98124-4019 RE: Seattle Shoreline Master Program Draft Regulations (2nd draft) Dear Ms. Glowacki: The Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Habitat Program has reviewed Seattle's Shoreline Master Program Draft Regulations dated October 2011. Attached are our comments regarding these regulations in the interest of protecting and restoring the Tribe's treaty-protected fisheries resources. We request an opportunity to meet and discuss these comments further with you before the City's completes its next version of these regulations. This wil give us an opportunity to clarify any of the comments as needed, as well as work on language changes that may be needed to address the comments. Please call me at 253-876-3116 to set up this meeting. We appreciate the opportunity to review this proposal and look forward to meeting with you soon. Sincerely, l)rJ,) (,_ ~'""fÎ(\ Karen Walter Watersheds and Land Use Team Leader Cc: Joe Burcar, WDOE, NW Region Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Division December 22, 2011 Comments to Seattle's SMP regulations 2nd draft Page 2 Comments to the Shoreline Master Program Regulations-Second Draft, October 2011 General comments 1. Aquaculture should be allowed in all shoreline designations. It is a priority use under the Shoreline Management Act and important for the Tribe's fisheries programs. Under the draft rules, aquaculture is only allowed as a conditional use in the UC; UG; UH; UI; UM designations. -

State of Washington and Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Education Compact

MUCKLESHOOT TRIBAL COUNCIL ~ 39015 172nd Avenue S.E. • Auburn, Washington 98092-9763 (253) 939-3311 • Fax (253) 931-8570 I RESOLUTION NO. \ 1 .., d' \ \ i ijj TO PROVIDE FOR THE EXTENSION OF THE STATE -TRIBAL a. COMPACT RELATING TO THE MUCKLESHOOT TRIBAL SCHOOL AND TO PROVIDE FOR A FIVE YEAR TERM WHEREAS, the Muckleshoot Indian Tribal Council is the duly constituted governing body for the Muckleshoot Indian Reservation by the authority of, and is herein acting solely pursuant to, its constitution and by-laws approved May 13, 193 6, by the Secretary ofthe Interior, and as amended June 28, 1977, and not pursuant to its Indian Reorganization Act Corporate Charter ratified October, 31, 1936; and WHEREAS, in 2014 the Muckleshoot Tribe and the Washington State Superintendent of Public Education entered into a joint Tribal-State Compact intended to provide state funding to the Tribal School under the authority of RCW 28A. 715; and WHEREAS, the term of the 2014 Compact was three years ending September 3, 2017; and, WHEREAS, the Muckleshoot Tribe and Superintendent wish to renew the current Compact for an additional five year term ending September 3, 2022; and, WHEREAS, in agreeing to renew and continue the current compact for an additional five year term the parties have agreed upon certain modifications which are incorporated into the attached State-Tribal Compact where said State-Tribal Compact is attached to this Resolution and made a part hereof as if setout fully herein; and, WHEREAS, the Tribal Council has determined it is in the best interest of the Tribe that the attached State-Tribal Compact be approved. -

King County and Western Washington Cultural Geography, Communities, Their History and Traditions - Unit Plan

Northwest Heritage Resources King County and Western Washington Cultural Geography, Communities, Their History and Traditions - Unit Plan Enduring Cultures Unit Overview: Students research the cultural geographies of Native Americans living in King County and the Puget Sound region of Washington (Puget Salish), then compare/contrast the challenges and cultures of Native American groups in King County and Puget Sound to those of Asian immigrant groups in the same region. Used to its fullest, this unit will take nine to ten weeks to complete. Teachers may also elect to condense/summarize some of the materials and activities in the first section (teacher-chosen document-based exploration of Native American cultures) in order to focus on the student-directed research component. List of individual lesson plans: Session # Activity/theme 1 Students create fictional Native American families, circa 1820-1840, of NW coastal peoples. 2* Students introduce the characters, develop their biographies as members of specific tribes (chosen from those in the Northwest Heritage Resources website searchable database) 3* The fictional characters will practice a traditional art. Research NWHR database to browse possibilities, select one. Each student will learn something about the specific form s/he chose for his/her characters. Students will also glean from actual traditional artists' biographies what sorts of challenges the artists have faced and what sorts of goals they have that are related to their cultural traditions and communities. 4* Cultural art forms: Students deepen their knowledge of one or more art forms. 5 Teacher creates basic frieze: large map of Oregon territory and Canadian islands/ coastal region. -

Tribal Ceded Areas in Washington State

Blaine Lynden Sumas Fern- Nooksack Oroville Metaline dale Northport Everson Falls Lummi Nation Metaline Ione Tribal Ceded Areas Bellingham Nooksack Tribe Tonasket by Treaty or Executive Order Marcus Samish Upper Kettle Republic Falls Indian Skagit Sedro- Friday Woolley Hamilton Conconully Harbor Nation Tribe Lyman Concrete Makah Colville Anacortes Riverside Burlington Tribe Winthrop Kalispel Mount Vernon Cusick Tribe La Omak Swinomish Conner Twisp Tribe Okanogan Colville Chewelah Oak Stan- Harbor wood Confederated Lower Elwha Coupeville Darrington Sauk-Suiattle Newport Arlington Tribes Klallam Port Angeles The Tulalip Tribe Stillaguamish Nespelem Tribe Tribes Port Tribe Brewster Townsend Granite Marysville Falls Springdale Quileute Sequim Jamestown Langley Forks Pateros Tribe S'Klallam Lake Stevens Spokane Bridgeport Elmer City Deer Everett Tribe Tribe Park Mukilteo Snohomish Grand Hoh Monroe Sultan Coulee Port Mill Chelan Creek Tribe Edmonds Gold Bothell + This map does not depict + Gamble Bar tribally asserted Index Mansfield Wilbur Creston S'Klallam Tribe Woodinville traditional hunting areas. Poulsbo Suquamish Millwood Duvall Skykomish Kirk- Hartline Almira Reardan Airway Tribe land Redmond Carnation Entiat Heights Spokane Medical Bainbridge Davenport Tribal Related Boundaries Lake Island Seattle Sammamish Waterville Leavenworth Coulee City Snoqualmie Duwamish Waterway Bellevue Bremerton Port Orchard Issaquah North Cheney Harrington Quinault Renton Bend Cashmere Rockford Burien Wilson Nation -

Coast Salish Culture – 70 Min

Lesson 2: The Big Picture: Coast Salish Culture – 70 min. Short Description: By analyzing and comparing maps and photographs from the Renton History Museum’s collection and other sources, students will gain a better understanding of Coast Salish daily life through mini lessons. These activities will include information on both life during the time of first contact with White explorers and settlers and current cultural traditions. Supported Standards: ● 3rd Grade Social Studies ○ 3.1.1 Understands and applies how maps and globes are used to display the regions of North America in the past and present. ○ 3.2.2 Understands the cultural universals of place, time, family life, economics, communication, arts, recreation, food, clothing, shelter, transportation, government, and education. ○ 4.2.2 Understands how contributions made by various cultural groups have shaped the history of the community and the world. Learning Objectives -- Students will be able to: ● Inspect maps to understand where Native Americans lived at the time of contact in Washington State. ● Describe elements of traditional daily life of Coast Salish peoples; including food, shelter, and transportation. ● Categorize similarities and differences between Coast Salish pre-contact culture and modern Coast Salish culture. Time: 70 min. Materials: ● Laminated and bound set of Photo Set 2 Warm-Up 15 min.: Ask students to get out a piece of paper and fold it into thirds. 5 min.: In the top third, ask them to write: What do you already know about Native Americans (from the artifacts you looked at in the last lesson)? Give them 5 min to brainstorm. 5 min.: In the middle, ask them to write: What do you still want to know? Give them 5min to brainstorm answers to this. -

Washington State Tribal Reservations and Draft Treaty Ceded Areas

f f o r t t y- our h de gr Nooksack Tribe ee of l ongi t t Lummi Tribe ude w e s s Columbia Reservation f r m o Moses Reservation W July 2, 1872 - July 1, 1892 a April 19, 1879 - May 1, 1885 Longitude 121.02 degrees west west degrees 121.02 Longitude hi ngt on ( on D C Upper Skagit Tribe ) Samish Tribe Swinomish Tribe Makah Tribe Kalispel Tribe Treaty of Neah Bay Colville Confederated Tribes 1/31/1855 Sauk-Suiattle Tribe Stillaguamish Tribe Columbia Reservation Elwha Klallam Tribe April 1872 - July 1872 Tulalip Tribe Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe Quileute Tribe Treaty of Quinault River Treaty of Point Elliott Spokane Tribe Port Gamble S’Kallam Tribe July 1, 1855 January 22, 1855 Hoh Tribe Treaty of Point No Point January 26, 1855 Suquamish Tribe Longitude 119 degrees, 10 minutes 10 minutes 119 degrees, Longitude PointSouthworth Snoqualmie Tribe Three Tree (Pulley) Point Quinault Tribe Skokomish Tribe Coeur dAlene, Southern Spokane, and other bands Relinquishment, Executive order, November 8, 1873 Muckleshoot Tribe Puyallup Tribe Squaxin Island Tribe Treaty of Medicine Creek B l December 26, 1854 ac k H Nisqually Tribe Latitude 47 degrees i l l s Yakima Treaty of Camp Stevens Mt. Rainier June 9, 1855 Chehalis Confederated Tribes Shoalwater Bay Tribe W h i te B lu La Lac ? ff Chehalis, Cowlitz, Klatsop, Chinook, Klikitat and other tribes s Relinquishment, Executive order, July 8, 1864 Nes Perce Treaty of Camp Stevens Cowlitz Tribe Tohmah-luke ? June 11, 1855 Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation Walla Walla Treaty of Camp Stevens Blue Mtns. -

1855 Treaty of Point Elliott

Treaty of Point Elliott, 1855 Articles of agreement and convention made and concluded at Muckl-te-oh, or Point Elliott, in the territory of Washington, this twenty-second day of January, eighteen hundred and fifty-five, by Isaac I. Stevens, governor and superintendent of Indian affairs for the saidTerritory, on the part of the United States, and the undersigned chiefs, head-men and delegates of the Dwamish, Suquamish, Sk-kahl-mish, Sam-ahmish, Smalh-kamish, Skope-ahmish, St-kah-mish, Snoqualmoo, Skai-wha-mish, N'Quentl-ma-mish, Sk-tah-le-jum, Stoluck-wha-mish, Sno-ho-mish, Skagit, Kik-i-allus, Swin-a-mish, Squin-ah-mish, Sah-ku- mehu, Noo-wha-ha, Nook-wa-chah-mish, Mee-see-qua-guilch, Cho-bah-ah-bish, and othe allied and subordinate tribes and bands of Indians occupying certain lands situated in said Territory of Washington, on behalf of said tribes, and duly authorized by them. ARTICLE 1. The said tribes and bands of Indians hereby cede, relinquish, and convey to the United States all their right, title, and interest in and to the lands and country occupied by them, bounded and described as follows: Commencing at a point on the eastern side of Admiralty Inlet, known as Point Pully, about midway between Commencement and Elliott Bays; thence eastwardly, running along the north line of lands heretofore ceded to the United States by the Nisqually, Puyallup, and other Indians, to the summit of the Cascade range of mountains; thence northwardly, following the summit of said range to the 49th parallel of north latitude; thence west, along said -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Categorization in Motion: Duwamish Identity, 1792-1934 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/75s2k9tm Author O'Malley, Corey Susan Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Categorization in Motion: Duwamish Identity, 1792-1934 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Corey Susan O’Malley 2017 © Copyright by Corey Susan O’Malley 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Categorization in Motion: Duwamish Identity, 1792-1934 by Corey Susan O’Malley Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Rebecca J. Emigh, Chair This study uses narrative analysis to examine how racial, ethnic, and national schemas were mobilized by social actors to categorize Duwamish identity from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. In so doing, it evaluates how the classificatory schemas of non- indigenous actors, particularly the state, resembled or diverged from Duwamish self- understandings and the relationship between these classificatory schemes and the configuration of political power in the Puget Sound region of Washington state. The earliest classificatory schema applied to the Duwamish consisted of a racial category “Indian” attached to an ethno- national category of “tribe,” which was honed during the treaty period. After the “Indian wars” of 1855-56, this ethno-national orientation was supplanted by a highly racialized schema aimed at the political exclusion of “Indians”. By the twentieth century, however, formalized racialized exclusion was replaced by a racialized ethno-national schema by which tribal membership was defined using a racial logic of blood purity.