Narratives of Poets' Personal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Original / Powersurge IMAGE Banshee

NOTES CARDS WITH LINKS TO PICS (BLUE), FOLLOWED BY THOSE LISTED IN BOLD ARE HIGHEST PRIORITY I NEED MULTIPLES OF EVERY CARD LISTED, AS WELL AS PACKS, DECKS, UNCUT SHEETS, AND ENTIRE COLLECTIONS Original / Powersurge IMAGE Banshee - Character 5 Multipower Power Card Black Cat - Femme Fatale 8 Anypower Card Cyclops - Remove Visor 6 Anypower + 2 Basic Universe (Power Blast - Spawn) Ghost Rider - Hell on Wheels Any Character's - Flight, Massive Muscles, & Super Speed Human Torch - Character Artifacts (Linkstone, Myrlu Symbiote, The Witchblade) Iceman - Character Backlash - Mist Body Iron Man - Character Brass - Armored Powerhouse & Weapons Array Jubilee - Prismatic Flare Curse - Brutal Dissection Juggernaut - Battering Ram Darkness - Demigod of the Dark Rogue - Mutant Misslile Events - Witchblade on the Scene Scarlet Witch - Hex Power & Sorceress Slam (Non-Error) Grifter - Nerves of Steel Grunge - Danger Seeker IQ Killrazor - Outer Fury Any Hero - Power Leech Malebolgia - Character & Signed in Blood Apocalypse - Character Overtkill - One-Man Army Bishop - Character & Temporal Anomaly Ripclaw - Character & Native Magic Cable - Character & Askani' Son Shadowhawk - Backsnap & Brutal Revenge Carnage - Anarchy Spawn - Protector of the Innocent Deadpool - Don't Lose Your Head! Stryker - Armed and Dangerous Doctor Doom - Character & Diplomatic Immunity Tiffany - Character & Heavenly Agent Dr. Strange - Character Velocity - Internal Hardware, Quick Thinking, & Speedthrough Iron Man Character Violator - Darklands Army Ghost Rider - Character Voodoo -

2020 Upper Deck Marvel Anime Checklist

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto Serial #'d Odds Point Base Set 1 Captain Marvel 24 Base Set 2 Wolverine 24 Base Set 3 Iron Man 24 Base Set 4 Hulk 24 Base Set 5 Ghost Rider 24 Base Set 6 Black Widow 24 Base Set 7 Ultron 24 Base Set 8 Gambit 24 Base Set 9 Rogue 24 Base Set 10 Cyclops 24 Base Set 11 Ant-Man 24 Base Set 12 Silver Samurai 24 Base Set 13 Spider-Man 24 Base Set 14 Falcon 24 Base Set 15 Black Panther 24 Base Set 16 Thor 24 Base Set 17 Kid Kaiju 24 Base Set 18 Adam Warlock 24 Base Set 19 Captain America 24 Base Set 20 Juggernaut 24 Base Set 21 She-Hulk 24 Base Set 22 Magneto 24 Base Set 23 Spider-Woman 24 Base Set 24 Sentry 24 Base Set 25 Doctor Strange 24 Base Set 26 Emma Frost 24 Base Set 27 Mirage 24 Base Set 28 Scarlet Witch 24 Base Set 29 Quicksilver 24 Base Set 30 Namor 24 Base Set 31 Moon Knight 24 Base Set 32 Wasp 24 Base Set 33 Elektra 24 Base Set 34 Dagger 24 Base Set 35 Cloak 24 Base Set 36 Thanos 24 Base Set 37 Phoenix 24 Base Set 38 Piper 24 Base Set 39 Iron Lad 24 Base Set 40 Black Knight 24 Base Set 41 Psylocke 24 Base Set 42 X-23 24 Base Set 43 Nick Fury 24 Base Set 44 Forge 24 Base Set 45 Loki 24 Base Set 46 Gamora 24 Base Set 47 Beta Ray Bill 24 Base Set 48 Onslaught 24 Base Set 49 Nebula 24 Base Set 50 Groot 24 Base Set 51 Rocket Raccoon 24 Base Set 52 Grandmaster 24 Base Set 53 Winter Soldier 24 Base Set 54 Iceman 24 Base Set 55 Professor X 24 Base Set 56 Colossus 24 Base Set 57 Bucky Barnes 24 Base Set 58 Black Bolt 24 Base Set 59 Beast 24 Base Set 60 Kitty Pryde 24 Base Set 61 Luke Cage 24 Base Set -

The Silver Surfer Story/Outline

THE SILVER SURFER STORY/OUTLINE DRAFT 1 “BATTLECRY” WRITTEN BY LARRY BRODY TEASER 1. EXT. THE SOUL MASTER DIMENSION. A scene we’ve witnessed before—but a more pleasant version this time. It’s the SILVER SURFER, SHALLA BAL, and the VIRAL OVERMIND, working together to save Zenn-La and the rest of the planets in this dimension. Except that this time Shalla Bal is not left behind. Instead, she makes it through just in time, rushing into the Silver Surfer’s arms! The Surfer starts to kiss her, and now Shalla Bal vanishes, only her voice remaining, crying out that she is in a dark, frightening place, and begging for the Surfer’s help in getting her out. 2. EXT. SPACE NEAR ZENN-LA. The Surfer soars all around, searching—and awakens to discover that he is flying upward from the now safe Zenn-La…and that everything that just happened was a dream. Yet even now he hears Shalla 2 Bal calling to him, her voice fading out only after the dream has ended. 3. As the Surfer ponders this, he realizes that he is hearing another distress call through a COM BEAM. It’s the leader of a group of REFUGEES, fleeing from a planet that has just fallen to the KREE EMPIRE, and asking for a safe haven. Right behind the Refugees is a KREE FLEET, and the pursuers begin FIRING THEIR ENERGY WEAPONS, hitting not only the Refugees but the Silver Surfer as well! He’s hit again and again in rapid succession, reeling weakly to one knee, as we FADE OUT. -

X-Men/Avengers: Onslaught Vol

X-MEN/AVENGERS: ONSLAUGHT VOL. 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jeph Loeb | 448 pages | 29 Oct 2020 | Marvel Comics | 9781302923990 | English | New York, United States X-men/avengers: Onslaught Vol. 2 PDF Book In July during a revamp of the X-Men franchise, its title changed to New X-Men , featuring an ambigram logo issue X-Men: Legacy initially followed the Professor's presumed road to recovery as well as the encounters he faced, such as a battle with the mutant Exodus on the psychic plane [12] and discoveries about his past that include Mr. Comic book series. Log in Sign up. This was particularly unique during the late s when most X-Men titles frequently had story arcs that were several issues long. Iron Boy, Quicksilver, Black Panther and Hank Pym are making their way through the sewers looking for safety at the Wakanda embassy as the Sentinels continue to attack New York city above. This listing has ended. Cancel Update. Similar sponsored items Feedback on our suggestions - Similar sponsored items. And the goblin faces his greatest enemy - his self-esteem! To this end he got the assistance of Hellfire Club's leader Sebastian Shaw and Nate's old nemesis Holocaust , [12] however Holocaust was soon defeated. See details. It's the final battle that will change the landscape of the Marvel Universe! Onslaught's threat to the world became apparent when the heroes noticed that the creature used Franklin's powers to create a second sun that was drawing closer to the Earth, threatening to wipe out all life upon its approach. -

Download X-Men: the Road to Onslaught Volume 2 Free Ebook

X-MEN: THE ROAD TO ONSLAUGHT VOLUME 2 DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Scott Lobdell, Alan Davis, Terry Kavanagh | 440 pages | 15 Jul 2014 | Marvel Comics | 9780785188308 | English | New York, United States The Road to Onslaught by Terry Kavanagh, Scott Lobdell and Alan Davis (2014, Paperback) Then, Bishop struggles with holding onto his sanity due to reality and time hopping complications. Ryan Duncan rated it really liked it Jul 22, All this, and the Xavier Institute enrolls a new student! Nothing offensive, just boring. Retrieved 2 February X-Factor by Peter David. Read more X- Men: The Road to Onslaught Volume 2 by Daniel Way. Venom 23—42, Just X-men perfection. Let's hope that the final volume has more content. X-Men: The Age of Apocalypse. Daredevil —, Annual 10 and additional pages from the original Fall from Grace trade paperback. Wolverine —, Annual '99 ; Wolverine: Origin 1—6. X-Men: Prelude to Age of Apocalypse. Let's X-Men: The Road to Onslaught Volume 2 you back to tracking and discussing your comics! The art is loud and colourful, at least, so one can enjoy that as long as the ridiculous Barbie-esque proportions of basically every single female character, even the ones in the background, don't bother you too much and goofy one-offs like the X- People playing poker with The Thing. Fantastic Four 48—50, 55, 57—60, 72, 74—77 and material from Tales to Astonish 92—93 and Fantastic Four 56, 61, Annual 5. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Noriel rated it really liked it Dec 20, Newer Post Older Post Home. -

Achievements Booklet

ACHIEVEMENTS BOOKLET This booklet lists a series of achievements players can pursue while they play Marvel United: X-Men using different combinations of Challenges, Heroes, and Villains. Challenge yourself and try to tick as many boxes as you can! Basic Achievements - Win without any Hero being KO’d with Heroic Challenge. - Win a game in Xavier Solo Mode. - Win without the Villain ever - Win a game with an Anti-Hero as a Hero. triggering an Overflow. - Win a game using only Anti-Heroes as Heroes. - Win before the 6th Master Plan card is played. - Win a game with 2 Players. - Win without using any Special Effect cards. - Win a game with 3 Players. - Win without any Hero taking damage. - Win a game with 4 Players. - Win without using any Action tokens. - Complete all Mission cards. - Complete all Mission cards with Moderate Challenge. - Complete all Mission cards with Hard Challenge. - Complete all Mission cards with Heroic Challenge. - Win without any Hero being KO’d. - Win without any Hero being KO’d with Moderate Challenge. - Win without any Hero being KO’d with Hard Challenge. MARVEL © Super Villain Feats Team vs Team Feats - Defeat the Super Villain with 2 Heroes. - Defeat the Villain using - Defeat the Super Villain with 3 Heroes. the Accelerated Villain Challenge. - Defeat the Super Villain with 4 Heroes. - Your team wins without the other team dealing a single damage to the Villain. - Defeat the Super Villain without using any Super Hero card. - Your team wins delivering the final blow to the Villain. - Defeat the Super Villain without using any Action tokens. -

Marvel Heroclix Giant Sized X-Men Onslaught Product Information Product Shipping in October

Marvel HeroClix Giant Sized X-Men Onslaught Product Information Product Shipping in October Sellable Unit: Stock # : 70 452 Title: Marvel Giant Sized X-Men Onslaught Unit UPC: 63448270452-3 Unit Size (inches) Case Pack: 2 Onslaught out of 8 total figs in a case Case Size (inches): 19.25”x12.375”x8.0 (Estimated) Case Gross Weight (pounds): 4.66 pounds Hang Tab: Yes Country of Origin: China Expected Release: November , 2011 70452 Marvel HeroClix : Giant-Sized X-Men Onslaught • Giant Sized X-Men Onslaught is one of the premier figures from the runaway hit Marvel HeroClix Giant-Size X-Men release! • Now available exclusively to Toys R’ Us, this figure has a completely different dial and New Character Cards from the one in the Giant-Size X-Men booster release, making it a must have for players and collectors. • Onslaught stands 5 inches tall in an ALL NEW fiery translucent color to this villain an . © 2011 WIZKIDS/NECA, LLC. All rights reserved. HeroClix and WizKids are trademarks of © 2011 WIZKIDS/NECA, LLC. TM & © 2011 Marvel www.marvel.com Marvel HeroClix Giant Sized X-Men Nemesis Product Information Product Shipping in October Sellable Unit: Stock # : 70 453 Title: Marvel Giant Sized X-Men Nemesis Unit UPC: 63448270453-0 Unit Size (inches) Case Pack: 6 Case Size (inches): 19.25”x12.375”x8.0 (Estimated) Case Gross Weight (pounds): 4.66 pounds Hang Tab: Yes Country of Origin: China Expected Release: November 2011 70453 Marvel HeroClix : Giant-Sized X-Men Nemesis • Nemesis is one of the premier figures from the runaway hit Marvel HeroClix Giant-Size X-Men release. -

Vs. System 2PCG

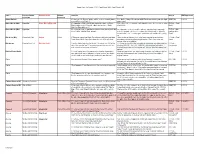

Upper Deck Vs System 2PCG Card Rules FAQ - Card Ruling FAQ Card 1 Keyword/Super Related Cards Related Question Answer Source UDE Approved Power/XP Keywords Adam Warlock If I don’t use his Emerge power, will he recover normally during Yes. But he’s huge! Spend that MIGHT and start bashing with him right UDE FAQ 6.10.16 my next Recovery Phase? away, man! Baron Mordo (MC) Hypnotize Sister Ripley/Ripley #8 If I Hypnotize a Ripley #8 L2 that started the game as Sister Ripley #8 Level 1. A character will always become the level one version FB Post - Chad Ripley, which Level 1 Character does she become? Sister of what it is. Daniel Ripley or Ripley#8 level 1? Baron Mordo (MC) Hypnotize Does Hex prevent a Hypnotized character from truning back into No, Hypnotize creates a modifier with an expiration that temporarily FB Post - Kirk Level 2 at the start of my next turn? makes a character its Level 1 version. When that modifer expires it (confirmed by becomes its Level 2 version again, and this is not conisdered Leveling Chad) up. Black Cat (MC) Cross their Path Satana Lethal If Satana is in play and Black Cat attacks a defender and uses Daze counts as stunning, but Lethal was changed to work when a FB Post - Chad Cross their Path to Daze that character, is it KO'd by Lethal? wounding a defending supporting character. Since Daze does not Daniel wound, lethal is not applied. Blackheart Created from Evil Even the Odds Even the Odds targeting Blackheart. -

Marvel Comics Avengers Chronological Appearances by Bob Wolniak

Marvel Comics Avengers Chronological Appearances By Bob Wolniak ased initially on the Bob Fronczak list from Avengers Assemble and Avengers Forever websites. But unlike Mr. B Fronczak’s list (that stops about the time of Heroes Reborn) this is NOT an attempt at a Marvel continuity (harmony of Marvel titles in time within the fictional universe), but Avengers appearances in order in approx. real world release order . I define Avengers appearances as team appearances, not individual Avengers or even in some cases where several individual Avengers are together (but eventually a judgment call has to be made on some of those instances). I have included some non-Avengers appearances since they are important to a key storyline that does tie to the Avengers, but noted if they did not have a team appearance. Blue (purple for WCA & Ultimates) indicates an Avengers title , whether ongoing or limited series. I have decided that Force Works is not strictly an Avengers title, nor is Thunderbolts, Defenders or even Vision/Scarlet Witch mini- series, although each book correlates, crosses over and frequently contains guest appearances of the Avengers as a team. In those cases, the individual issues are listed. I have also decided that individual Avengers’ ongoing or limited series books are not Avengers team appearances, so I have no interest in the tedious tracking of every Captain America, Thor, Iron Man, or Hank Pym title unless they contain a team appearance or x-over . The same applies to Avengers Spotlight (largely a Hawkeye series, with other individual appearances), Captain Marvel, Ms. Marvel, Vision, Wonder Man, Hulk, She-Hulk, Black Panther, Quicksilver, Thunderstrike, War Machine, Black Widow, Sub-Mariner, Hercules, and other such books or limited series. -

The Full Complaint Filed by Julie Taymor

2. Taymor, a world-famous director, writer, collaborator, and costume designer, worked on Spider-Man—including co-writing its book (also called a “libretto” or “script”)—for over seven years. In early 2011, the Musical’s producers removed Taymor from the production. Since then, they have continued to promote, use, change, and revise Taymor’s work, including her book of the Musical. They have done so without her approval or authorization and in violation of their agreements with Taymor and Taymor’s intellectual property rights, including her right to approve changes to her book of the Musical. They have refused to pay Taymor her contractually guaranteed authorship royalties. 3. By their actions, Defendants have: (a) violated Taymor’s rights under the Copyright Act; (b) breached their agreements with Taymor and LOH; and (c) threatened to violate Taymor’s right of privacy under Sections 50 and 51 of the New York Civil Rights Law. Taymor and LOH seek compensatory and statutory damages, a declaratory judgment, and injunctive relief. PARTIES 4. Plaintiff Julie Taymor is domiciled in this District. Taymor served as director, collaborator, co-bookwriter, and mask designer for Spider-Man. 5. Plaintiff LOH, Inc., is a domestic business corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of New York and having its principal place of business in this District. LOH is wholly owned by Taymor, who serves as President of the company. 6. Defendant 8 Legged Productions, LLC (“8 Legged”) is a domestic limited liability company organized and existing under the laws of the State of New York and having its principal place of business in this District. -

Avengers Chronology by Bob Fronczak

Avengers Chronology By Bob Fronczak Avengers 1 Avengers 1.5 Avengers 2 Untold Tales of Spiderman 3 Tales of Suspense 49 (Iron Man vs. the Angel. Other Avengers appear in civilian identities (cameos), unable to answer IM's call for assistance) Avengers 3 Avengers 4 Sentry 1 (FB) Fantastic Four 25 Fantastic Four 26 Avengers 5 Avengers 6 Marvels 2 Thor: Godstorm 1 Journey into Mystery 101 Journey into Mystery 105 Tales of Suspense 56 (Iron Man vs. the Unicorn. The Avengers try to contact IM during his battle but he fails to answer their summons. 3 panels.) Avengers 7 Journey into Mystery 108 Tales to Astonish 59 Amazing Spider-Man Annual 1 Tales of Suspense 58 (Iron Man vs. Capt. America. The Chameleon impersonates Cap and tricks IM into attacking him. Giant-Man and Wasp capture the Chameleon and end the fight Avengers 8 Amazing Spider-Man 18 Avengers 9 Tales of Suspense 59 Fantastic Four 31 Unlimited Access 2 Unlimited Access 3 Unlimited Access 4 Untold Tales of Spider-Man Annual 2 (Avengers join in the battle vs. Sundown) Tales of Suspense 60 Avengers 10 X-Men 9 Avengers 11 Avengers 12 Avengers 13 Avengers 14 Fantastic Four 36 (Avengers attend Reed Richards and Sue Storm's engagement party. 2 panels) Captain America 221 / 2 nd Story Avengers 15 Avengers 16 Marvel Heroes & Legends 97 (Revised and expanded version of Avengers 16) Journey Into Mystery 116 Thunderbolts 9 Avengers 17 Journey into Mystery 120 (Thor vs. the Absorbing Man. Thor appears at the Mansion to ask the Avengers aid. -

American Superhero Comics: Fractal Narrative and the New Deal a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts

American Superhero Comics: Fractal Narrative and The New Deal A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Lawrence W. Beemer June 2011 © 2011 Lawrence W. Beemer. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled American Superhero Comics: Fractal Narrative and The New Deal by LAWRENCE W. BEEMER has been approved for the English Department of Ohio University and the College of Arts and Sciences by ______________________________ Robert Miklitsch Professor of English ______________________________ Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT BEEMER, LAWRENCE W., Ph.D., June 2011, English American Superhero Comics: Fractal Narrative and The New Deal (204 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Robert Miklitsch Coining the term "fractal narrative," this dissertation examines the complex storytelling structure that is particular to contemporary American superhero comics. Whereas other mediums most often require narrative to function as self-contained and linear, individual superhero comics exist within a vast and intricate continuity that is composed of an indeterminate number of intersecting threads. Identical to fractals, the complex geometry of the narrative structure found in superhero comics when taken as a whole is constructed by the perpetual iteration of a single motif that was established at the genre's point of origin in Action Comics #1. The first appearance of Superman institutes all of the features and rhetorical elements that define the genre, but it also encodes it with the specific ideology of The New Deal era. In order to examine this fractal narrative structure, this dissertation traces historical developments over the last seven decades and offers a close reading Marvel Comics' 2006 cross-over event, Civil War.