LGBT Rights Law: a Career Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussion Guide University ER1.Pages

THE FREEDOM TO MARRY A Discussion Guide for University Students Page 1 Package Contents and Screening Notes Your package includes: • 86 minute version of the flm - the original feature length • 54 minute version of the flm - educational length • DVD Extras - additional scenes and bonus material • “Evan, Eddie and Te Wolfsons" (Runtime - 6:05) • “Evan Wolfson’s Early Predictions” (Runtime - 5:02) • “Mary Listening to the Argument” (Runtime - 10:29) • “Talia and Teir Strategy” (Runtime - 2:19) • Educational Guides • University Discussion Guide • High School Discussion Guide • Middle School Discussion Guide • A Quick-Start Discussion Guide (for any audience) • Sample “Questions and Answers” from the flm’s director, Eddie Rosenstein Sectioning the flm If it is desired to show the flm into shorter sections, here are recommended breaks: • 86 Minute Version (feature length) - Suggested Section Breaks 1) 00:00 - 34:48 (Ending on the words “It’s really happening.”) Total run time: 34:38 2) 34:49 - 56:24 (Ending on “Equal justice under the law.”) Total run time: 21:23 3) 56:25 - 1:26:16 (Ending after the end credits.) Total run time: 28:16 • 54 Minute Version (educational length) - Suggested Section Breaks 1) 00:00 - 24:32 (Ending on the words “It’s really happening.”) Total run time: 24:32 2) 24:33 - 36:00 (Ending on “Equal justice under the law.”) Total run time: 10:15 3) 36:01 - 54:03 (Ending after the end credits.) Total run time: 18:01 Page 2 Introduction THE FREEDOM TO MARRY is the story of the decades-long battle over the right for same-sex couples to get married in the United States. -

Nds of Marriage: the Implications of Hawaiian Culture & Values For

Configuring the Bo(u)nds of Marriage: The Implications of Hawaiian Culture & Values for the Debate About Homogamy Robert J. Morris, J.D.* (Kaplihiahilina)** Eia 'o Hawai'i ua ao,pa'alia i ka pono i ka lima. Here is Hawai'i, having become enlightened, confirmed by justice in her hands.1 * J.D. University of Utah College of Law, 1980; degree candidate in Hawaiian Language, University of Hawai'i at Manoa. Mahalo nui to Daniel R. Foley; Evan Wolfson; Matthew R. Yee; Walter L. Williams; H. Arlo Nimmo; Hon. Michael A. Town; Len Klekner; Andrew Koppelman; Albert J. Schtltz; the editors of this Journal; and the anonymous readers for their assistance in the preparation of this Article. As always, I acknowledge my debt to feminist scholarship and theory. All of this notwithstanding, the errors herein are mine alone. This Article is dedicated to three couples: Russ and Cathy, Ricky and Mokihana, and Damian and his aikAne. Correspondence may be sent to 1164 Bishop Street #124, Honolulu, HI 96813. ** Kapd'ihiahilina, my Hawaiian name, is the name of the commoner of the island of Kaua'i who became the aikane (same-sex lover) of the Big Island ruling chief Lonoikamakahiki. These two figures will appear in the discussion that follows. 1. MARY KAWENA P0KU'I & SAMUEL H. ELBERT, HAWAIIAN DICTIONARY 297 (1986). This is my translation of a name song (mele inoa) for Lili'uokalani, the last monarch of Hawai'i. Her government was overthrown with the assistance of resident American officials and citizens January 14-17, 1893. The literature on this event is voluminous, but the legal issues are conveniently summarized in Patrick W. -

2009 Program Book

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN GHALLL OHF FAFME 2009 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Dana V. Starks Mayor Chairman and Commissioner Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues William W. Greaves, Ph.D. Director/Community Liaison COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, Suite 300 Chicago, Illinois 60654-3478 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) © 2009 Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame In Memoriam Robert Maddox Tony Midnite 2 3 4 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (now the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, their organizations and their friends, as well as their contributions to the LGBT communities and to the city of Chicago. -

Governs the Making of Photocopies Or Other Reproductions of Copyrighted Materials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. University of Nevada, Reno Wedding Bells Ring: How One Organization Changed the Face of LGBT Rights in Argentina A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS, INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS BACHELOR OF ARTS, SPANISH by ANNALISE GARDELLA Dr. Linda Curcio-Nagy, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor May, 2013 UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA THE HONORS PROGRAM RENO We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by ANNALISE GARDELLA entitled Wedding Bells Ring: How One Organization Changed the Face of LGBT Rights in Argentina be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS, INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS BACHELOR OF ARTS, SPANISH ______________________________________________ Dr. Linda Curcio-Nagy, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor ______________________________________________ Tamara Valentine, Ph.D., Director, Honors Program May, 2013 i Abstract During the 1970s, Argentina faced a harsh military dictatorship, which suppressed social movements in Argentine society and “disappeared” nearly 30,000 people. The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT) community became a specific target of this dictatorship. -

Phd Thesis Entitled “A White Wedding? the Racial Politics of Same-Sex Marriage in Canada”, Under the Supervision of Dr

A White Wedding? The Racial Politics of Same-Sex Marriage in Canada by Suzanne Judith Lenon A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto © Copyright by Suzanne Judith Lenon (2008) A White Wedding? The Racial Politics of Same-Sex Marriage in Canada Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Suzanne Judith Lenon Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract In A White Wedding? The Racial Politics of Same-Sex Marriage, I examine the inter-locking relations of power that constitute the lesbian/gay subject recognized by the Canadian nation-state as deserving of access to civil marriage. Through analysis of legal documents, Parliamentary and Senate debates, and interviews with lawyers, I argue that this lesbian/gay subject achieves intelligibility in the law by trading in on and shoring up the terms of racialized neo-liberal citizenship. I also argue that the victory of same-sex marriage is implicated in reproducing and securing a racialized Canadian national identity as well as a racialized civilizational logic, where “gay rights” are the newest manifestation of the modernity of the “West” in a post-9/11 historical context. By centring a critical race/queer conceptual framework, this research project follows the discursive practices of respectability, freedom and civility that circulate both widely and deeply in this legal struggle. I contend that in order to successfully shed its historical markers of degeneracy, the lesbian/gay subject must be constituted not as a sexed citizen but rather as a neoliberal citizen, one who is intimately tied to notions of privacy, property, autonomy and freedom of choice, and hence one who is racialized as white. -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California The Freedom to Marry Oral History Project Evan Wolfson Evan Wolfson on the Leadership of the Freedom to Marry Movement Interviews conducted by Martin Meeker in 2015 and 2016 Copyright © 2017 by The Regents of the University of California ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Evan Wolfson dated July 15, 2016. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Getting Down to Basics: Tools to Support LGBTQ Youth in Care, Child Welfare League a Place of Respect: a Guide for Group Care of Am

Getting Down to Basics Tools to Support LGBTQ Youth in Care Overview of Tool Kit Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) young people are in America’s child welfare and juvenile justice systems in disproportionate numbers. Like all young people in care, they have the right to be safe and protected. All too often, however, they are misunderstood and mistreated, leading to an increased risk of negative outcomes. This tool kit offers practical tips and information to ensure that LGBTQ young people in care receive the support and services they deserve. Developed in partnership by the Child Welfare League of America (CWLA) and Lambda Legal, the tool kit gives guidance on an array of issues affecting LGBTQ youth and the adults and organizations who provide them with out-of-home care. TOPICS INCLUDED IN THIS TOOL KIT 3 Basic Facts About Being LGBTQ 5 Information for LGBTQ Youth in Care 7 Families Supporting an LGBTQ Child FOSTERING TRANSITIONS 9 Caseworkers with LGBTQ Clients A CWLA/Lambda Legal 11 Foster Parents Caring for LGBTQ Youth Joint Initiative 13 Congregate Care Providers Working with LGBTQ Youth 15 Attorneys, Guardians ad Litem & Advocates Representing LGBTQ Youth 17 Working with Transgender Youth 21 Keeping LGBTQ Youth Safe in Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Placements 23 Working with Homeless LGBTQ Youth 25 Faith-Based Providers Working with LGBTQ Youth 27 Basic LGBTQ Policies, Training & Services for Child Welfare Agencies 29 Recommendations for Training & Education on LGBTQ Issues 31 What the Experts Say: Position & Policy Statements on LGBTQ Issues from Leading Professional Associations 35 LGBTQ Youth Resources 39 Teaching LGBTQ Competence in Schools of Social Work 41 Combating Misguided Efforts to Ban Lesbian & Gay Adults as Foster & Adoptive Parents 45 LGBTQ Youth Risk Data 47 Selected Bibliography CHILD WELFARE LEAGUE OF AMERICA CWLA is the nation’s oldest and largest nonprofit advocate for children and youth and has a membership of nearly 1000 public and private agencies, including nearly every state child welfare system. -

2016 Program Book

2016 INDUCTION CEREMONY Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame Gary G. Chichester Mary F. Morten Co-Chairperson Co-Chairperson Israel Wright Executive Director In Partnership with the CITY OF CHICAGO • COMMISSION ON HUMAN RELATIONS Rahm Emanuel Mona Noriega Mayor Chairman and Commissioner COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST Published by Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame 3712 North Broadway, #637 Chicago, Illinois 60613-4235 773-281-5095 [email protected] ©2016 Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame In Memoriam The Reverend Gregory R. Dell Katherine “Kit” Duffy Adrienne J. Goodman Marie J. Kuda Mary D. Powers 2 3 4 CHICAGO LGBT HALL OF FAME The Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame (formerly the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame) is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, its Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (later the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame (changed to the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 2015) in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. Today, after the advisory council’s abolition and in partnership with the City, the Hall of Fame is in the custody of Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame, an Illinois not- for-profit corporation with a recognized charitable tax-deductible status under Internal Revenue Code section 501(c)(3). -

How Doma, State Marriage Amendments, and Social Conservatives Undermine Traditional Marriage

TITSHAW [FINAL] (DO NOT DELETE) 10/24/2012 10:28 AM THE REACTIONARY ROAD TO FREE LOVE: HOW DOMA, STATE MARRIAGE AMENDMENTS, AND SOCIAL CONSERVATIVES UNDERMINE TRADITIONAL MARRIAGE Scott Titshaw* Much has been written about the possible effects on different-sex marriage of legally recognizing same-sex marriage. This Article looks at the defense of marriage from a different angle: It shows how rejecting same-sex marriage results in political compromise and the proliferation of “marriage light” alternatives (e.g., civil unions, domestic partnerships or reciprocal beneficiaries) that undermine the unique status of marriage for everyone. After describing the flexibility of marriage as it has evolved over time, the Article focuses on recent state constitutional amendments attempting to stop further development. It categorizes and analyzes the amendments, showing that most allow marriage light experimentation. It also explains why ambiguous marriage amendments should be read narrowly. It contrasts these amendments with foreign constitutional provisions aimed at different-sex marriages, revealing that the American amendments reflect anti-gay animus. But they also reflect fear of change. This Article gives reasons to fear the failure to change. Comparing American and European marriage alternatives reveals that they all have distinct advantages over traditional marriage. The federal Defense of Marriage Act adds even more. Unlike same-sex marriage, these alternatives are attractive to different-sex couples. This may explain why marriage light * Associate Professor at Mercer University School of Law. I’d like to thank Professors Kerry Abrams, Tedd Blumoff, Johanna Bond, Beth Burkstrand-Reid, Patricia A. Cain, Jessica Feinberg, David Hricik, Linda Jellum, Joseph Landau, Joan MacLeod Hemmingway, David Oedel, Jack Sammons, Karen Sneddon, Mark Strasser, Kerri Stone, and Robin F. -

LGBT+ Media Resource List

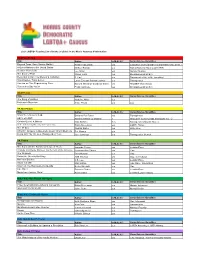

2021 LGBTQ+ Reading List of books available in the Morris Automated Information Network (M.A.I.N. Library) Adult Non-Fiction Title Author In M.A.I.N.? Genre/Intersectionalities Beyond Trans: Does Gender Matter? Heath Fogg Davis yes Legislative policy (gender neutral bathrooms, id etc.) A Queer History of the United States Michael Bronski yes history/historical figures (All LGBT) Gender: Your Guide Lee Airton yes Gender Studies The Book of Pride Mason Funk yes Biographies (all LGBT) Becoming a Man: The Story of a Transition P. Carl yes Transgender (late in life transition) Trans Bodies, Trans Selves Laura Erickson-Schroth (editor) yes Transgender America on Film: Representing Race, Harry M. Benshoff andSean Griffin yes All LGBT+/Race/Class TravelsClass, Gender in a Gay and Nation Sexuality at the Movies Philip Gambone yes Biographies (all LGBT) Adult Fiction Title Author In M.A.I.N.? Genre/Intersectionalities The Song of Achilles Madeline Miller yes Brokeback Mountain Annie Proulx yes gay YA Non-Fiction Title Author In M.A.I.N.? Genre/Intersectionalities Trans Teen Survival Guide Owl and Fox Fisher yes Transgender ABC's of LGBT+ Ash(ley) Hardell (or Mardell) ? All LGBT+ (good for kids and adults too :-)) Gender Queer: A Memoir Maia Kobabe Yes Transgender (Graphic Novel) Pride: Celebrating Diversity and Community Robin Stevenson yes LGBT+ History The 57 Bus Dashka Slater yes Hate crime What If?: Answers to Questions About What it Means to Eric Marcus yes BeingBe Gay Jazz: and MyLesbian Life as a (Transgender) Teen Jazz Jennings yes Transgender, Memoir YA Fiction Title Author In M.A.I.N.? Genre/Intersectionalities The Stars and the Blackness Between Them Junauda Petrus yes Lesbian/Race Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe Benjamin Alire Sáenz yes Gay The Whispers Greg Howard yes Gay Darius the Great is Not Okay Adib Khorram yes Gay, intercultural Not Your Sidekick C.B. -

Basic Reforms to Address the Unmet Needs of Lgbt Foster Youth

II. BASIC REFORMS TO ADDRESS THE UNMET NEEDS OF LGBT FOSTER YOUTH What emerges from our state-by-state survey is a picture of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth under-served by foster care systems. These youth remain in the margins, their best interests ignored and their safety in jeopardy. To remedy LGBT invisibility, prevent abuse, and improve care for these adolescents, we propose the following crucial, basic reforms in the areas of non-discrimination policies, training for foster parents and foster care staff,48 and LGBT youth services and programs. A. Non-discrimination policies States should adopt and enforce explicit, systemwide policies prohibiting discrimina- tion. Specifically, these should include prohibitions against discrimination on the basis of: the sexual orientation of foster care youth, the sexual orientation of foster parents and other foster household members, the sexual orientation of foster care staff, the HIV/AIDS status of foster care youth, the HIV/AIDS status of foster parents and other foster household members, and the HIV/AIDS status of foster care staff. These policies should encompass actual or perceived sexual orientation or HIV/ AIDS status. Discrimination prohibitions should also forbid discrimination on the basis of gender identity. Sex discrimination provisions should be interpreted to bar such discrimi- nation, and that scope can be made explicit by enumerating sex, including gender identity, among forbidden bases of discrimination in agency policies. Adopting LGBT non-discrimination policies is an important acknowledgment that LGBT youth are present in the foster care system in significant numbers and that they 22 Youth in the Margins often face prejudice, neglect, and abuse. -

Restoring Rationality to the Same- Sex Marriage Debate Jeffrey J

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 32 Article 2 Number 2 Winter 2005 1-1-2005 Square Circles - Restoring Rationality to the Same- Sex Marriage Debate Jeffrey J. Ventrella Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey J. Ventrella, Square Circles - Restoring Rationality to the Same-Sex Marriage Debate, 32 Hastings Const. L.Q. 681 (2005). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol32/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Square Circles?!! Restoring Rationality to the Same-Sex "Marriage" Debate by JEFFERY J. VENTRELLA, ESQ.* Domestic partnership or civil union has passed in every country in the European Union, and in Japan and Canada. Why not in America? Because we are the only one that's really Christian. It seems to me that the single biggest enemy to homosexuality is Christianity.... Any self-respecting gay should be an atheist. And so I think it's a battle worth fighting, not because I want to live behind a white picket fence and be faithful to a lover and both wear wedding rings - I think that's stupid.' We find everywhere a clear recognition of the same truth... because of a general recognition of this truth the question has seldom been presented to the courts.... These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterance that this is a Christian nation...