Getting to Know Bridge, Camera Raw, and Photoshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Snapshots: How to Take That Fancy Dslr Camera Off Auto and Photograph Your Life Like a Pro Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BEYOND SNAPSHOTS: HOW TO TAKE THAT FANCY DSLR CAMERA OFF AUTO AND PHOTOGRAPH YOUR LIFE LIKE A PRO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rachel Devine, Peta Mazey | 224 pages | 14 Jun 2012 | Watson-Guptill Publications | 9780817435806 | English | New York, United States Beyond Snapshots: How to Take That Fancy DSLR Camera Off Auto and Photograph Your Life Like a Pro PDF Book If you tend to shoot indoors, you may want to consider also investing in a faster lens. Although it is not the first photography book I have read, I still feel like I learned a lot. If you're just starting out, you don't want to spend thousands of dollars on a camera and lenses you might never use. This is from the 'situations' section where I present 5-minute primers for common situations. They're quick and easy to master, and once you know them, you'll never forget them. While it has many of the same features as its predecessor the D , including a They consist of a camera body to which interchangeable lenses can be added. The touch-screen is clear and bright, and the layout of the menus and options available makes things simple to navigate. You heard that right! The Sony Cyber-shot RX10 IV is a premium super-zoom all-in-one bridge camera with a megapixel 1- inch sensor and a long-range mm equivalent zoom, all packed into a robust, ergonomic body. Silhouettes are all about shape and contrast, so pay special attention to these details. I'd never thought about taking shots after the sun has set. -

Hardware and Software for Panoramic Photography

ROVANIEMI UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES SCHOOL OF TECHNOLOGY Degree Programme in Information Technology Thesis HARDWARE AND SOFTWARE FOR PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPHY Julia Benzar 2012 Supervisor: Veikko Keränen Approved _______2012__________ The thesis can be borrowed. School of Technology Abstract of Thesis Degree Programme in Information Technology _____________________________________________________________ Author Julia Benzar Year 2012 Subject of thesis Hardware and Software for Panoramic Photography Number of pages 48 In this thesis, panoramic photography was chosen as the topic of study. The primary goal of the investigation was to understand the phenomenon of pa- noramic photography and the secondary goal was to establish guidelines for its workflow. The aim was to reveal what hardware and what software is re- quired for panoramic photographs. The methodology was to explore the existing material on the topics of hard- ware and software that is implemented for producing panoramic images. La- ter, the best available hardware and different software was chosen to take the images and to test the process of stitching the images together. The ex- periment material was the result of the practical work, such the overall pro- cess and experience, gained from the process, the practical usage of hard- ware and software, as well as the images taken for stitching panorama. The main research material was the final result of stitching panoramas. The main results of the practical project work were conclusion statements of what is the best hardware and software among the options tested. The re- sults of the work can also suggest a workflow for creating panoramic images using the described hardware and software. The choice of hardware and software was limited, so there is place for further experiments. -

Understanding Image Formats and When to Use Them

Understanding Image Formats And When to Use Them Are you familiar with the extensions after your images? There are so many image formats that it’s so easy to get confused! File extensions like .jpeg, .bmp, .gif, and more can be seen after an image’s file name. Most of us disregard it, thinking there is no significance regarding these image formats. These are all different and not cross‐ compatible. These image formats have their own pros and cons. They were created for specific, yet different purposes. What’s the difference, and when is each format appropriate to use? Every graphic you see online is an image file. Most everything you see printed on paper, plastic or a t‐shirt came from an image file. These files come in a variety of formats, and each is optimized for a specific use. Using the right type for the right job means your design will come out picture perfect and just how you intended. The wrong format could mean a bad print or a poor web image, a giant download or a missing graphic in an email Most image files fit into one of two general categories—raster files and vector files—and each category has its own specific uses. This breakdown isn’t perfect. For example, certain formats can actually contain elements of both types. But this is a good place to start when thinking about which format to use for your projects. Raster Images Raster images are made up of a set grid of dots called pixels where each pixel is assigned a color. -

The Musk Duck Photography Special

The Musk Duck Photography Special Compiled by Ian Ashton November 2020 Chaffinch 1977 UK England, Mamiya SLR and 135mm prime lens with extension tubes. Ian Ashton Here we are in November 2020 and most of Birdlife Ballarat’s planned syllabus meetings and outings have been cancelled including this year’s photography competition due to the Pandemic. I was to give a talk back in June, it was titled, ‘How times have changed’, an old-fashioned slide show. So, in place of that and to acknowledge that some of our members are not just bird watchers, this Musk Duck photography special was conceived. Birdlife Ballarat does not have a dedicated photography group, but many members do own cameras. It may be that in these uncertain times some members have contemplated buying a camera or upgrading their equipment or their knowledge. I thought it would be good to share some ideas and techniques. Left, my very first SLR was a Mamiya 500 like this one. The 500 related to the shutter speed, 1,500th of a second. My present camera can take photos at 1,4000th Of a second. Times and technology have changed. MD Photo Special Birdwatching and bird photography do not always sit well together, but of course most birdwatchers enjoy seeing photographs of birds. At one end we have the birdwatcher and at the other end the photographer and between these two ends there are as many combinations of the two as you can imagine. The best bird photographers know their subject and can have immense amounts of knowledge and patience to achieve the outcome they are aiming for. -

USER MANUAL Media Asset Management

USER MANUAL XMAM Media Asset Management (Rev. 1.2 ENG) axeltechnology.com ENG CONTENT 1 USERS MANUAL ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.1 FEATURES ........................................................................................................................................................................4 1.2 HOW TO USE XMAM .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2.1 SHARED FOLDERS ..........................................................................................................................................................4 1.2.2 HOW TO ACCESS XMAM WEB .......................................................................................................................................5 1.2.3 FINDING RESOURCES ....................................................................................................................................................6 1.2.3.1 RECENT RESOURCES ...........................................................................................................................................6 1.2.3.2 SIMPLE SEARCH ...................................................................................................................................................6 -

Megaplus Conversion Lenses for Digital Cameras

Section2 PHOTO - VIDEO - PRO AUDIO Accessories LCD Accessories .......................244-245 Batteries.....................................246-249 Camera Brackets ......................250-253 Flashes........................................253-259 Accessory Lenses .....................260-265 VR Tools.....................................266-271 Digital Media & Peripherals ..272-279 Portable Media Storage ..........280-285 Digital Picture Frames....................286 Imaging Systems ..............................287 Tripods and Heads ..................288-301 Camera Cases............................302-321 Underwater Equipment ..........322-327 PHOTOGRAPHIC SOLUTIONS DIGITAL CAMERA CLEANING PRODUCTS Sensor Swab — Digital Imaging Chip Cleaner HAKUBA Sensor Swabs are designed for cleaning the CLEANING PRODUCTS imaging sensor (CMOS or CCD) on SLR digital cameras and other delicate or hard to reach optical and imaging sur- faces. Clean room manufactured KMC-05 and sealed, these swabs are the ultimate Lens Cleaning Kit in purity. Recommended by Kodak and Fuji (when Includes: Lens tissue (30 used with Eclipse Lens Cleaner) for cleaning the DSC Pro 14n pcs.), Cleaning Solution 30 cc and FinePix S1/S2 Pro. #HALCK .........................3.95 Sensor Swabs for Digital SLR Cameras: 12-Pack (PHSS12) ........45.95 KA-11 Lens Cleaning Set Includes a Blower Brush,Cleaning Solution 30cc, Lens ECLIPSE Tissue Cleaning Cloth. CAMERA ACCESSORIES #HALCS ...................................................................................4.95 ECLIPSE lens cleaner is the highest purity lens cleaner available. It dries as quickly as it can LCDCK-BL Digital Cleaning Kit be applied leaving absolutely no residue. For cleaing LCD screens and other optical surfaces. ECLIPSE is the recommended optical glass Includes dual function cleaning tool that has a lens brush on one side and a cleaning chamois on the other, cleaner for THK USA, the US distributor for cleaning solution and five replacement chamois with one 244 Hoya filters and Tokina lenses. -

Photographers Guide to the Nikon Coolpix P600 Ebook

PHOTOGRAPHERS GUIDE TO THE NIKON COOLPIX P600 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alexander S White | 424 pages | 01 Jun 2014 | White Knight Press | 9781937986254 | English | none Photographers Guide to the Nikon Coolpix P600 PDF Book Software Manuals Firmware Software. Moreover, I enjoy landscape photography with my Nikon camera. Sign in. Step 1 Tripod Mount. Although your device does not support this download service, it can be used to view download information. Disappointingly the P still doesn't support the RAW file format, something that all of its main competitors offer, and a prosumer feature that frankly we'd expect on this class of camera. And mostly all apps are accessible from Android to iPhone users. Necessary Always Enabled. We've combed through the options and selected our two favorite cameras in this class. The book explains all shooting modes, menus, functions, and controls of this superzoom camera in clear language, accompanied by more than illustrations and sample photographs. Baby Blues Mobile Lightroom Presets. Just list the features most important to you like 4k video, fully automatic mode, etc. Nikon retain ownership of the Manual and all copies thereof and all related intellectual property rights, and reserves all rights not expressly granted to you under this Agreement. Cancel: I did not complete this guide. The shutter release, zoom lever and power button are in the same locations as on the P, as is the same customisable Function button. This camera has a 35x optical zoom lens with macro capability. Not to mention, it has high-quality features and allows you to add a creative spin to your photography. -

Certified Digital Designer Professional Certification Examination Review

Digital Imaging & Editing and Digital & General Photography Certified Digital Designer Professional Certification Examination Review Within this presentation – We will use specific names and terminologies. These will be related to specific products, software, brands and trade names. ADDA does not endorse any specific software or manufacturer. It is the sole decision of the individual to choose and purchase based on their personal preference and financial capabilities. the Examination Examination Contain at Total 325 Questions 200 Questions in Digital Image Creation and Editing Image Editing is applicable to all Areas related to Digital Graphics 125 Question in Photography Knowledge and History Photography is applicable to General Principles of Photography Does not cover Photography as a General Arts Program Examination is based on entry level intermediate employment knowledge Certain Processes may be omitted that are required to achieve an end result ADDA Professional Certification Series – Digital Imaging & Editing the Examination Knowledge of Graphic and Photography Acronyms Knowledge of Graphic Program Tool Symbols Some Knowledge of Photography Lighting Ability to do some basic Geometric Calculations Basic Knowledge of Graphic History & Theory Basic Knowledge of Digital & Standard Film Cameras Basic Knowledge of Camera Lens and Operation General Knowledge of Computer Operation Some Common Sense ADDA Professional Certification Series – Digital Imaging & Editing This is the Comprehensive Digital Imaging & Editing Certified Digital Designer Professional Certification Examination Review Within this presentation – We will use specific names and terminologies. These will be related to specific products, software, brands and trade names. ADDA does not endorse any specific software or manufacturer. It is the sole decision of the individual to choose and purchase based on their personal preference and financial capabilities. -

Which Image Format

CASE STUDY Which Image Format PNG PNG (Portable Network Graphics), an extensible file format for the lossless, portable, well-compressed storage of raster images. PNG provides a patent-free replacement for GIF and can also replace many common uses of TIFF. Indexed-color, gray scale, and true color images are supported, plus an optional alpha channel. Sample depths range from 1 to 16 bits. However, the format is not widely supported in common image programs. AVI AVI stands for Audio Video Interleave and is currently the most common file format for storing audio/video data on the PC. AVI’s are 8-bit per image plane. This file format conforms to the Microsoft Windows Resource Interchange File Format (RIFF) specification, which makes it convenient for sharing the image sequence between computers. AVI files (which typically end in the .avi extension) require a specific player that supports. RAW A RAW image format contains minimally processed data from the image sensor. RAW literally means unprocessed or uncooked. RAW images must be processed and converted to RGB format if it is a color image. Photron however, does not limit RAW as a unprocessed image. The “Bayer” check box must be selected to save the RAW image as an unprocessed image. RAW images have 8-bits per image plane. RAWW A RAWW image format contains minimally processed data from the image sensor. RAWW images must be processed and converted to RGB format if it is a color image. Photron however, does not limit RAWW as a unprocessed image. The “Bayer” check box must be selected to save the RAWW image as an unprocessed image. -

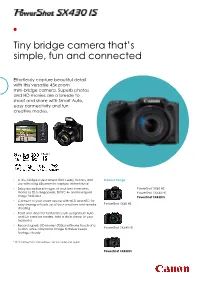

Tiny Bridge Camera That's Simple, Fun and Connected

Tiny bridge camera that’s simple, fun and connected Effortlessly capture beautiful detail with this versatile 45x zoom mini-bridge camera. Superb photos and HD movies are a breeze to shoot and share with Smart Auto, easy connectivity and fun creative modes. • A tiny, bridge-style camera that’s easy to carry and Product Range use with a big 45x zoom to capture distant detail • Enjoy exceptional images of your best memories, PowerShot SX60 HS thanks to 20.0 Megapixels, DIGIC 4+ and Intelligent PowerShot SX540 HS Image Stabilizer PowerShot SX430 IS • Connect to your smart device with Wi-Fi and NFC for easy sharing or back up of your creations and remote PowerShot SX60 HS shooting • Point and shoot for fantastic results using Smart Auto and fun creative modes. Add a date stamp to your memories • Record superb HD movies (720p) with one touch of a button, while a Dynamic Image Stabilizer keeps PowerShot SX540 HS footage steady * Wi-Fi connectivity and features vary by model and region. PowerShot SX430 IS Technical Specifications IMAGE SENSOR SHOOTING Type 1/2.3 type CCD Modes Smart Auto (32 scenes detected), Program AE, Live View [14] Effective Pixels Approx. 20.0M Control, Portrait, Face Self-Timer, Low Light (5.0MP), Monochrome, Fish-eye Effect, Toy Camera Effect, Effective / Total Pixels Approx. 20.5M Miniature Effect, Super Vivid, Poster Effect, Fireworks, Long Shutter IMAGE PROCESSOR Photo Effects My Colors (My Colors Off, Vivid, Neutral, Sepia, Black & Type DIGIC 4+ White, Positive Film, Lighter Skin Tone, Darker Skin Tone, Vivid Blue, Vivid Green, Vivid Red, Custom Color) LENS Drive modes Single, Continuous, Self-Timer Focal Length 4.3 – 193.5 mm (35 mm equivalent: 24 – 1080 mm) Continuous Shooting Approx. -

A Review of Oculoplastic Photography: a Guide for Clinician Photographers

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.733 A Review Of Oculoplastic Photography: A Guide For Clinician Photographers Chin T. Ong 1 , Jun Fai Yap 2 , Yong Zheng Wai 2 , Qi Xiong Ng 2 1. Ophthalmology, Beacon International Specialist Hospital 2. Ophthalmology, University of Malaya Corresponding author: Chin T. Ong, [email protected] Abstract Clinical photography in the field of oculoplastic surgery has many applications. It is possible for clinicians to obtain standardized clinical photographs without a studio. A clinician photographer has the advantage of knowing exactly what to photograph as well as having immediate access to the images. In order to maintain standardization in the photographs, the photographic settings should remain constant. This article covers essential photographic equipment, camera settings, patient pose, and digital asset management. Categories: Medical Education, Ophthalmology Keywords: clinical photography, standardization, oculoplastic surgery Introduction And Background Clinical photographs are useful for clinical records, research, audit, education, and in supporting medico- legal cases [1-3]. Standardized clinical photographs are often taken by medical photographers using professional grade photographic equipment in dedicated studios. However, it is possible for clinicians to obtain high quality clinical photographs using simpler photographic equipment outside a studio [4]. There are many benefits if a clinician takes patient photographs. The clinician photographer knows without instructions exactly which area of the body to photograph. The photographic session can take place during the patient consultation with no further delays for the patient [1]. The images are instantly available to the clinician and can be shown to the patient during the consultation process. Standardization The most important concept in oculoplastic photography is standardization [1, 4-5]. -

Cph001 Cameras, Lenses and the Digital Image

CPH001 CAMERAS, LENSES AND THE DIGITAL IMAGE CPH001 – CAMERAS, LENSES AND THE DIGITAL IMAGE Table of Contents WELCOME ............................................................................................................... 6 THE PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESS ........................................................................... 7 DIGITAL CAMERA TYPES ....................................................................................... 8 DSLR CAMERAS .................................................................................................. 8 INTERCHANGEABLE LENSES ......................................................................... 9 INTEGRATED LIGHT METERS ......................................................................... 9 DEPTH OF FIELD PREVIEW BUTTON ............................................................. 9 MIRRORLESS CAMERAS .................................................................................. 10 POINT AND SHOOT CAMERAS ......................................................................... 11 HYBRID CAMERAS ............................................................................................ 12 CHOOSING YOUR CAMERA BODY ................................................................... 13 LENSES .................................................................................................................. 15 FIXED LENSES (SMALL, MEDUIM AND TELEPHOTO): .................................... 16 ZOOM LENSES (SMALL, MEDIUM AND TELEPHOTO): .................................... 17 MACRO