View/Print Page As PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upon This Rock

UPON THIS ROCK An Expostion of the Glories of Christ in Matthew 16:13-18 B. P. Harris Upon this Rock An Exposition of the Glories of Christ in Matthew 16:13-18 Along with the Foundation of the Faith Including an excerpt from Church Principles of the New Testament, Vol. 1, where a fuller version may be found. B. P. Harris Assembly Bookshelf 2017 All Scriptures are taken from the King James Version unless otherwise indicated. “Scripture taken from the NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE, Copyright1960, 1962, 1963,1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission.” Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Some Scriptural texts are sourced from: BibleWorks™ Copyright © 1992-2008 BibleWorks, LLC. All rights reserved. BibleWorks was programmed by Michael S. Bushell, Michael D. Tan, and Glenn L. Weaver. All rights reserved. The English Translation of The Septuagint Version of the Old Testament by Sir Lancelot C. L. Brenton, 1844, 1851, published by Samuel Bagster and Sons, London, original ASCII edition Copyright © 1988 by FABS International (c/o Bob Lewis, DeFuniak Springs FL 32433). All rights reserved. Used by permission. Apocryphal portion not available. Copyright © 1998-1999, by Larry Nelson (Box 2083, Rialto, CA, 92376). Used by permission. RSV - Revised Standard Version of the Bible. Copyright © 1952 [2nd edition, 1971] by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by arrangement through the University of Pennsylvania, CCAT, which compared and corrected collated electronic versions supplied by William B. -

Best Evidence We're in the Last Days

October 21, 2017 Best Evidence We’re In the Last Days Shawn Nelson Can we know when Jesus is coming back? Some people have tried to predict exactly when Jesus would come back. For example, Harold Camping predicted Sep. 6, 1994, May 21, 2011 and Oct. 21 2011. There have been many others.1 But the Bible says we cannot know exact time: Matthew 24:36 --- “But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, but My Father only.” Acts 1:7 --- “And He said to them, “It is not for you to know times or seasons which the Father has put in His own authority.” We might not know the exact time, but we can certainly see the stage is being set: Matthew 16:2-3 --- ‘He answered and said to them, “When it is evening you say, ‘It will be fair weather, for the sky is red’; and in the morning, ‘It will be foul weather today, for the sky is red and threatening.’ Hypocrites! [speaking to Pharisees about events of his 1st coming] You know how to discern the face of the sky, but you cannot discern the signs of the times.’ 1 Thessalonians 5:5-6 --- “5 But concerning the times and the seasons, brethren, you have no need that I should write to you. 2 For you yourselves know perfectly that the day of the Lord so comes as a thief in the night… 4 But you, brethren, are not in darkness, so that this Day should overtake you as a thief. -

The Temple Mount/Haram Al-Sharif – Archaeology in a Political Context

The Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif – Archaeology in a Political Context 2017 March 2017 Table of contents >> Introduction 3 Written by: Yonathan Mizrachi >> Part I | The history of the Site: How the Temple Mount became the 0 Researchers: Emek Shaveh Haram al-Sharif 4 Edited by: Talya Ezrahi >> Part II | Changes in the Status of the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif 0 Proof-editing: Noa Granot from the 19th century to the Present Day 7 Graphic Design: Lior Cohen Photographs: Emek Shaveh, Yael Ilan >> Part III | Changes around the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif and the 0 Mapping: Lior Cohen, Shai Efrati, Slava Pirsky impact on the Status Quo 11 >> Conclusion and Lessons 19 >> Maps 20 Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an Israeli NGO working to prevent the politicization of archaeology in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and to protect ancient sites as public assets that belong to members of all communities, faiths and peoples. We view archaeology as a resource for building bridges and strengthening bonds between peoples and cultures. This publication was produced by Emek Shaveh (A public benefit corporation) with the support of the IHL Secretariat, the Federal Department for Foreign Affairs Switzerland (FDFA) the New Israeli Fund and CCFD. Responsibility for the information contained in this report belongs exclu- sively to Emek Shaveh. This information does not represent the opinions of the above mentioned donors. 2 Introduction Immediately after the 1967 War, Israel’s then Defense Minister Moshe Dayan declared that the Islamic Waqf would retain their authority over the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif compound. -

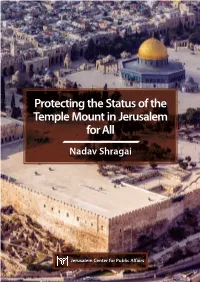

Protecting the Status of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem for All

The old status quo on the Temple Mount no longer exists and has lost its relevance. It has changed substantially according to a host of key parameters in a manner that has greatly enhanced the status of Muslims on the Mount and greatly undermined the status of Israeli Jews at the site. The situation on the Temple Mount continues to change periodically. The most blatant examples are the strengthening of Jordan’s position, the takeover of the Mount by the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel and then its removal, and the severe curtailment of visits by Jews on the Mount. Protecting the Status of the At the same time, one of the core elements of the old status quo – the prohibition against Temple Mount in Jerusalem Jews praying on the Temple Mount – is strictly maintained. It appears that this is the most for All stable element in the original status quo. Unfortunately, the principle of freedom of Nadav Shragai religion for all faiths to visit and pray on the Temple Mount does not exist there today. Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Protecting the Status of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem for All Nadav Shragai Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 2016 Read this book online: http://jcpa.org/status-quo-temple-mount/ Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Beit Milken, 13 Tel Hai St., Jerusalem, 92107, Israel Email: [email protected] Tel: 972-2-561-9281 Fax: 972-2-561-9112 © 2016 by Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Cover image by Andrew Shiva ISBN: 978-965-218-131-2 Contents Introduction: The Temple Mount as a Catalyst for Palestinian Violence 5 Major Findings 11 The Role of the Temple Mount in the Summer 2014 Terror Wave 13 Changes on the Temple Mount following the October 2015 Terror Wave 19 The Status Quo in 1967: The Arrangement and Its Components 21 Prominent Changes in the Status Quo 27 1. -

The Third Temple

The Third Temple Revelation 11:1-2 – March 14, 2021 The site where the Temple mount sits is the same place Abraham 4000 years ago met with a priest of the true God named Melchisedec (Genesis 14, Hebrews 5-7). A few years later, Abraham went to this site to offer his son Isaac as a sacrifice, but God provided, a ram for him to offer instead (Genesis 22). The First Temple: Approximately 1000 years later, in 988 BC, King David purchased this same site from a local resident named Ornan (1 Chronicles 21.) Twelve years after that, in 975 BC, King Solomon dedicated the First Jewish Temple. Prior to that, Israel worshipped in a place known as the Tabernacle (a tent made with badgers’ skin). They did this for 470-years.1 That is, from Moses to King David, Israel worship at the tent known as the Tabernacle. But when the First Temple was completed (1 Kings 5-8) tradition tells us Israel dismantled the Tabernacle and stored it under the Temple Mount. The First Temple was twice as large as the tabernacle. It was made of immense quarried stone and cedar and many of its items were covered in gold. It stood for approximately 366 years. It was destroyed by the Babylonians on the 9th of Av, 586 BC (The month of Av relates to late July or early August). Unique aspects of the Tabernacle and Temple. 1. Both the Tabernacle and the Temple were built according a pattern revealed by God. “For when Moses was about to erect the taBernacle, he was instructed by God, saying, ‘See that you make everything according to the pattern that was shown you on the mountain.’” (Hebrews 8:5). -

3. God's Third Temple: from Altars to the Temple of Herod

3. God’s Third Temple: From altars to the temple of Herod INTRODUCTION: ALTARS OF WORSHIP IN GENESIS God made the universe, and humankind, to be his temples. He wanted to be ‘at home’ in the universe, and especial- ly with humanity. Something went dreadfully wrong, howev- er, as man disobeyed God. The impact of this was that man could no longer ‘walk with God’ as a natural thing, and the world was no longer the perfect place God had wanted it to be. But all hope was not lost. God could still be found, but for this, religious liturgy was needed; After Adam and Eve were evicted from Paradise, their sons Cain and Abel began to sacrifice ‘fruit of the ground’ and ‘of the firstborn of the flock and of their fat portions’. For some of those offerings. ‘the Lord had regard’, for others he did not.1 After the Flood, Noah built an altar to the LORD’ and took animals and burnt them on the altar. ‘When the LORD smelled the pleasing aroma, the Lord said in his heart, “I will never again curse the ground because of man.’2 1. Genesis 4:3-5 2. Genesis 8:26-27 39 Abraham ‘built an altar to the LORD’ between Bethel and Ai and ‘called upon the name of the LORD’.3 Then God told Abraham to build an altar in the land of Moriah, and offer there a burnt offering. Initially Abraham was asked to sacrifice his son, but God provided a ram in the last mo- ment, testing the obedience of Abra- ham: And Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt offering instead of his son. -

Jerusalem: Five Decades of Subjection and Marginalization

Successive bloody incidents occurred in Jerusalem: Jerusalem during the first half of 2014 that Five Decades of surprised and shocked observers on both sides of the “Green Line,” especially since the Subjection and general conviction prevailing amongst them Marginalization was that “the issue of Jerusalem is over”; that the occupation had succeeded in taking full Nazmi Jubeh control of the land and its people; and that the process of unification and annexation had been crowned with success, so that now many of Jerusalem’s youth now taste nothing other than Israeli products, spend all their time in West Jerusalem, and listen only to Hebrew songs; that thousands of them have obtained or desire to obtain Israeli citizenship; that the plan for the complete separation of Jerusalem and the West Bank has been realized through the rings of settlements, diversionary roads, and the so- called separation wall; that the Palestinian sector of Jerusalem’s economy has been completely destroyed and made totally subordinate to Israel’s as a marginal service economy; and, finally, that the Israeli occupation has dealt a deathblow to the institutional infrastructure and suppressed Jerusalem’s Palestinian political elite. It would please Israeli politicians to declare, with pride and self-aggrandizement, that Jerusalem’s Palestinians desire to link their fate with that of Israel rather than with the Palestinian Authority. They are used to higher incomes compared with the incomes of their compatriots in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. They have grown accustomed to advanced health and social security services, since families with numerous children receive support from national insurance, while retirees and widowers receive financial aid. -

Should Israel Build the Third Temple?

Mon 15 July 2013 / 9 Av 5773 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Discussion for Tish’a b’Av eve Should Israel build the Third Temple? Background -Tish'a b'Av commemorates the destruction of the two Temples in Jerusalem -The First Temple, destroyed by the Babylonians in 587 BCE -The Second Temple, destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE Also, many other tragedies in Jewish history happened on that day, by accident or design. -For 2000 years Jews have prayed for the rebuilding of the Temple (Bet HaMikdash). -Rebuilding was not possible because the site was controlled by the Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Arabs, Seljuks, Crusaders, Mongols, Mamelukes, Turks, British, and Jordanians. -But Jews control the site today, since 7 June 1967, for the first time since biblical days. -Although most nations feel they have a say in what happens to Jerusalem. -A group called “The Temple Mount Faithful” routinely tries to set up a foundation stone for the Third Temple on Tisha b'Av, and the Israeli police routinely stop them. So, should we rebuild the Temple? Yes: -More and more Jews want it -We long for it daily in traditional Jewish prayers -It's our historical right -It would be a focal point, a rallying point for world Jewry No: -Don't want to go back to sacrificial worship. -Can only be on Temple Mount in Jerusalem (close to Western Wall). But that site is occupied by the Islamic Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque, third holiest site in Islam. Islamists would wage holy war. -

The Davidson Center, the Archaeological Park, and the Corner of the Western Wall

Tourism and Sacred Sites: The Davidson Center, the Archaeological Park, and the corner of the Western Wall 2015 August 2015 Written by: Raz Kletter Researchers: Yonathan Mizrachi, Gideon Sulymani Research assistant: Anna Veeder Translation: Talya Ezrahi Hebrew editor: Dalia Tessler Proof-editing: Dana Hercbergs Graphic design and Map: Lior Cohen Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an organization of archaeologists and heritage professionals focusing on the role of tangible cultural heritage in Israeli society and in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We view archaeology as a resource for strengthening understanding between different peoples and cultures. This publication was produced by Emek Shaveh (A public benefit corporation) with the support of the Norwegian Embassy in Israel, the Federal Department for Foreign Affairs Switzerland (FDFA), the Irish Foreign Ministry and Cordaid. Responsibility for the information contained in this report belongs exclusively to Emek Shaveh. This information does not represent the opinions of the abovementioned donors. Table of contents The Davidson Center 4 Construction of the center, funding, administration and the legal situation 5 The Israel Antiquities Authority safeguards the Davidson Center from “religious” elements 8 Davidson Center through a sewage tunnel 12 The Israel Antiquities Authority and Elad in one tunnel, along the Western Wall 16 Ideology and money 20 Additional projects – all of the remains are “ours” 22 Conclusion 22 Following the 1967 war and the destruction of the Mughrabi quarter, the Western Wall was informally split into two sections separated by the Mughrabi Bridge. To the north, the Western Wall Plaza, defined as sacred and used for prayer, was placed under the auspices of the Ministry for Religious Affairs. -

Fathom Review

Fathom Review LUKE AKEHURST LIAM HOARE MICHAEL ALLEN RONEN HOFFMAN SHLOMO AVINERI ALAN JOHNSON JAMES BLOODWORTH YOSSI KUPERWASSER GABRIEL NOAH BRAHM TZIPI LIVNI JOEL BRAUNOLD DAVID LOWE SARAH BROWN AMICHAI MAGEN DAVID CESARANI PHILIP MENDES NAOMI CHAZAN ALAN MENDOZA BEN COHEN ELHANAN MILLER URI DROMI CARY NELSON NOGA EMANUEL YIFAT OVADIA MATTI FRIEDMAN DAVE RICH EVE GARRARD JOEL SALMON LAMIS SHIBLI GHADIR COLIN SHINDLER SIR MARTIN GILBERT JONATHAN SPYER DORE GOLD ASHER SUSSER MARC GOLDBERG KENNETH WALTZER EFRAIM HALEVY MICHAEL WALZER YOAZ HENDEL MICHAEL WEGIER JEFFREY HERF GABRIEL WEIMANN MICHAEL HERZOG MICHAEL WEISS SARA HIRSCHHORN EINAT WILF DAVID HIRSH 2015 ‘It’s great to see this new journal. It’s accessible and provides expert analysis on strategic, cultural and economic issues relating to Israel. Amidst a lot of a sloganeering, Fathom provides nuanced discussion. As such, it fills a real gap.’ Amnon Rubinstein, Israeli law scholar, politician, and columnist. A member of the Knesset between 1977 and 2002, he served in several ministerial positions. ‘Awesome. Good original writing. A really fresh new addition.’ Amir Mizroch, Editor of Israel Hayom in English. ‘Many people have deeply held beliefs and passionate opinions about Israel and the Middle East. Very few people actually know about Israel and the Middle East. Fathom is an excellent source for those who wish to join the camp of those who actually know something about Israel, rather than just have an opinion about it.’ Einat Wilf, a member of the Knesset for the Labour Party and Independence from 2009-2013. ‘Fathom is an insightful, measured and thought provoking publication.’ Professor Clive Jones, Chair in Regional Security School of Government and International Affairs, University of Durham. -

FROM EGYPT to REHOBOTH a Spiritual Roadmap to Peace

Project-Genesis Interfaith January 2019 FROM EGYPT TO REHOBOTH A Spiritual Roadmap to Peace PRESENTED: Saturday, January 19, 2019 7:00pm Peconic Landing Greenport, NY Sunday, January 20, 2019 4:00pm Shrine of Our Lady of the Island Manorville, NY Monday, February 11, 2019 7:00pm Leonardo Plaza Hotel Jerusalem, Israel 1 AROUND THE WELL-AROUND A WALL Three Wells as Three Temples “And Isaac's servants dug in the valley, and they found there a well of living waters. And the shepherds of Gerar quarreled with Isaac's shepherds, saying, ‘The water is ours’; so he named the well Esek, because they had contended with him. And they dug another well, and they quarreled about it also; so he named it Sitnah. And he moved away from there, and he dug another well, and they did not quarrel over it; so he named it Rehoboth, and he said, ‘Now the Lord has made room for us, and we will be fruitful in the land.’" (Gen. 26: 19-22) In 1951, my parents left Yemen with nearly 50,000 other Jews during a mass exodus. They were running away from their homes in a land that became too hostile toward the Zionist project in Palestine. But they also believed it was a sign that the Messiah had come, and they walked for a year across the Arabian desert, following an invisible path back to their ancestral homeland. My father, then seven years old, had to walk, while my mother, a five-year- old, rode in a basket strapped to a donkey. -

Old City Map M H NR BEN Shadadterminal KO in a E Tomb Museum Gate H M

S H E Zurim Valley K Birgham H S EL National Park Young M A -A H E EL A-ZA A I E S H R M A I S A L IBN RA RI University A S E AR A H A D OM D E N R Q ’ S A A I U R NUR A-DIN H AYA E M D I HAHOMA HASHELISHIT - A M N T L E L L B V E E I IS E U H I K M SH H M D E EM O I H UEL S A’ S BE N H N ADAYA EL ASFAHANI S A N S R A L JERUSALEM L E S A H H N E E Bus D U C ICK HANEVI’I AD SH The Garden -D R Rockefeller IBN SINA The Old City Map M H NR BEN SHADADTerminal KO IN A E Tomb Museum Gate H M ( LEIMAN N TAN SU The Via Dolorosa - A SUL Storks L B Tower E HELENI HAMALKA L Herod’s Gate A U N S IMA Sha’ar HaPerahim R ULE The Stations of the Cross ) N S S HANEVI’IM TA I L A U S J E S E HA’AYIN HET T A R V D I I Zedekiah’s C N H H A Cave O S D H R A D N L . E M I E H T. H Damascus Gate R A L O MISHMAROT - F H E ANT DANIEL O Sha’ar Shechem A L QADISIYE (SHA T S I EL V ONIA I ’DIYA R D E Sha’ar MA IBN EL ES SA O Orson Heid S A Y T Shechem OMAR R ’THANA U A Sq.