Biographical Investigation Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pichini to Be Honored Life Insurance by Jeff Lyons Advancement of Women in Both the Profes- Sion and the Community

INSIDE! ® BENCH-BAR PREVIEW September 2006 The Monthly Newspaper of the Philadelphia Bar Association Vol. 35, No. 9 2006 Sandra Day O’Connor Award Guaranteed Pichini to be Honored Life Insurance by Jeff Lyons advancement of women in both the profes- sion and the community. The award presen- Available to Roberta D. Pichini, a former chair of the tation will be made during the Association’s Women in the Profession Committee, has Quarterly Meeting and Luncheon on Oct. 30. been selected as the recipient of the Asso- “Bobbie is a rare combination of a very Bar Members ciation’s 2006 Sandra Day O’Connor Award. talented and skilled lawyer who has attained The award is conferred annually on a prominence in her field of practice while Philadelphia Bar Association members woman attorney who has demonstrated finding time to devote to her family and who are actively employed can now take superior legal talent, achieved significant mentoring other women lawyers,” said advantage of a new universal life insurance legal accomplishments and has furthered the continued on page 21 Pichini product with benefits of $150,000 offered on a guaranteed issue basis. Flexible Premium Adjustable Life Insur- 2006 Bench-Bar Conference ance with Living Benefits has been endor- sed by the Association and is available ex- clusively to Association members. It is un- “Greatest Show on Earth” Sept. 29 - 30 derwritten by Transamerica Occidental Life Insurance Company of Cedar Rapids, Ia., The Philadelphia Bar Associa- and is made available through USI Colburn. tion’s 2006 Bench-Bar Confer- Previously, members only had the option ence, to be held at the Tropicana of Bar-endorsed term life insurance. -

Is the United States an Outlier in Public Mass Shootings? a Comment on Adam Lankford

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: https://journaltalk.net/articles/5980/ ECON JOURNAL WATCH 16(1) March 2019: 37–68 Is the United States an Outlier in Public Mass Shootings? A Comment on Adam Lankford John R. Lott, Jr.1 and Carlisle E. Moody2 LINK TO ABSTRACT In 2016, Adam Lankford published an article in Violence and Victims titled “Public Mass Shooters and Firearms: A Cross-National Study of 171 Countries.” In the article he concludes: “Despite having less than 5% of the global population (World Factbook, 2014), it [the United States] had 31% of global public mass shooters” (Lankford 2016, 195). Lankford claims to show that over the 47 years from 1966 to 2012, both in the United States and around the world there were 292 cases of “public mass shooters” of which 90, or 31 percent, were American. Lankford attributes America’s outsized percentage of international public mass shooters to widespread gun ownership. Besides doing so in the article, he has done so in public discourse (e.g., Lankford 2017). Lankford’s findings struck a chord with President Obama: “I say this every time we’ve got one of these mass shootings: This just doesn’t happen in other countries.” —President Obama, news conference at COP21 climate conference in Paris, Dec. 1, 2015 (link) 1. Crime Prevention Research Center, Alexandria, VA 22302. 2. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23187; Crime Prevention Research Center, Alexan- dria, VA 22302. We would like to thank Lloyd Cohen, James Alan Fox, Tim Groseclose, Robert Hansen, Gary Kleck, Tom Kovandzic, Joyce Lee Malcolm, Craig Newmark, Scott Masten, Paul Rubin, and Mike Weisser for providing helpful comments. -

The Current and Future State of Gun Policy in the United States, 104 J

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 104 Article 5 Issue 4 Symposium On Guns In America Fall 2015 The urC rent And Future State Of Gun Policy In The nitU ed States William J. Vizzard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation William J. Vizzard, The Current And Future State Of Gun Policy In The United States, 104 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 879 (2015). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol104/iss4/5 This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/15/10404-0879 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 104, No. 4 Copyright © 2015 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. THE CURRENT AND FUTURE STATE OF GUN POLICY IN THE UNITED STATES WILLIAM J. VIZZARD* In spite of years of journalistic and public attention and debate, the United States has instituted few changes in firearms policy over the past century. Opposition diluted a brief push by the Roosevelt administration in the 1930s and resulted in two minimalist federal statutes. A second effort in the wake of the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King produced the Gun Control Act of 1968, which largely remains the primary federal law. Even this modest control effort was subsequently diluted by the Firearms Owners Protection Act of 1986. -

We Shall Overcome”

"Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that." Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. ACTIVITIES MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. MARTIN KING LUTHER MONDAY, JANUARY 19, 2015 2015 STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA STATE 2015 COMMEMORATION & CELEBRATION & CELEBRATION COMMEMORATION SPONSORED BY Dr. Christina King Farris is the eldest sister of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the only living member of the family of origin. Dr. Farris recently retired as the oldest member of the faculty at Spelman College in Atlanta College where she graduated in the same year her brother Martin graduated from Morehouse College. This greeting is an exclusive to the 2015 State MLK Celebration in tribute to West Virginia’s recognition of Dr. King’s birthday as a State holiday before it became a National holiday. To Governor Earl Ray Tomblin and Dr. Carolyn Stuart, Executive Director of the Herbert Henderson Office of Minority Affairs, I bring greetings to the Martin Luther King Jr., State Holiday Commission and the people of the “Mountain State” of West Virginia, where “Mountaineers are always free”. I was surprised and pleased to learn that West Virginia led the nation in declaring Dr. King’s Birthday a State Holiday before it became a national holiday. I understand that this was the result of House Bill 1368 initiated by Delegates Booker Stephens and Ernest Moore which established the King Holiday as a State Celebration in 1982—four years before it was officially declared a national holiday in 1986. I pray that God’s richest blessing be with all who diligently work for justice, equality, and peace in pursuit of my brother’s vision of the “beloved community.” Dr. -

Special Programming on Radio Stations in the US Inspirational Irish

Special Programming on Radio Stations in the U.S. WOOX(AM) New Rochelle NV 1 hr WCDZ(FM) Dresden TN 4 hrs WRRA AMj Frederiksted VI 12 hrs ' WCSN(FM) Cleveland OH 1 hr 'WBRS(FM) Waltham MA 4 hrs WKCR-FM New York NY 2 hrs WSDO(AM) Dunlap TN 7 hrs KGNW AM) Burien -Seattle WA WKTX(AM) Cortland OH 12 hrs WZLY(FM) Wellesley MA 1 hr WHLD(AM) Niagara Falls NY WEMB(AM) Erwin TN 10 hrs KNTR( ) Ferndale WA 10 hrs WWKTL(FM) Struthers OH 1 hr WVFBE(FM) Flint MI 1 hr WXLG(FM) North Creek NY WHEW AM Franklin TN 3 hrs KLLM(FM) Forks WA 4 hrs WVQRP(FM) West Carrollton OH WVBYW(FM) Grand Rapids MI WWNYO(FM) Oswego NY 3 hrs WMRO AM Gallatin TN 13 tirs KVAC(AM) Forks WA 4 hrs 3 hrs 2 hrs WWXLU(FM) Peru NY WLMU(FM) Harrogate TN 4 hrs 'KAOS(FM) Olympia WA 2 hrs WSSJ(AM) Camden NJ 2 hrs WDKX(FM) Rochester NY 7 hrs WXJB -FM Harrogate TN 2 hrs KNHC(FM) Seattle WA 6 hrs WGHT(AM) Pompton Lakes NJ WWRU -FM Rochester NY 3 hrs WWFHC(FM) Henderson TN 5 hrs KBBO(AM) Yakima WA 2 hrs Inspirational 2 hrs WSLL(FM) Saranac Lake NY WHHM -FM Henderson TN 10 tirs WTRV(FM) La Crosse WI WFST(AM) Carbou ME 18 hrs KLAV(AM) Las Vegas NV 1 hr WMYY(FM) Schoharie NY WQOK(FM) Hendersonville TN WLDY(AM) Ladysmith 1M 3 hrs WVCIY(FM) Canandaigua NY WNYG(AM) Babylon NY 4 firs WVAER (FM) Syracuse NY 3 hrs 6 hrs WBJX(AM) Raane WI 8 hrs ' WCID(FM) Friendship NY WVOA(FM) DeRuyter NY 1 hr WHAZ(AM) Troy NY WDXI(AM) Jackson TN 16 hrs WRCO(AM) Rlohland Center WI WSI(AM) East Syracuse NY 1 hr WWSU(FM) Watertown NY WEZG(FM) Jefferson City TN 4 firs 3 hrs Irish WVCV FM Fredonia NY 3 hrs WONB(FM) Ada -

The Life of Martin Luther King Jr

The Life of Martin Luther King jr. By: Sadie Morales 5th Grade Our Lady of Guadalupe Parents and Family Before we start talking about what Martin Luther King jr. actually did, we are going to talk about his family. Why? Because this also had a vital role on helping Martin Luther King become who he was. His parents names where Martin Luther King sr., who was his father and Alberta Williams King, who was his mother. His father was a preacher, just like his son would be. His mother was a teacher. They got married in 1926. Shortly after, Martin sister was born in 1927. Then Martin Luther King, in 1929. A year later, his brother was born in 1930. His parents had a big influence on who he was. His parents taught him about injustices and how to respond to them. His mother taught him about the history of slavery and told “Even though some people make you feel bad or angry, you should not show it. You are as good as anyone else”. As Martin Luther King grew, he began to notice and understand this. In the top left, Martin Luther King jr.’s Parents, Martin Luther King sr., and Alberta Williams King. In the top right, Martin Luther King as a kid, and as a adult speaking. In the bottom left , Martin and his siblings, Christine King Farris and A.D. King. Childhood Martin Luther King had a happy childhood. He and his siblings learned to play the piano from their mother, and were taught spirituality by their father. -

Campus News February 6, 1998 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Campus News University Publications 2-6-1998 Campus News February 6, 1998 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/campus_news Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Campus News February 6, 1998" (1998). Campus News. 1234. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/campus_news/1234 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campus News by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAMPUS NEWS LA SALLE UNIVERSITY’S WEEKLY INFORMATION CIRCULAR February 0 6 , 1998 La Salle University Student Life Office [215] 951-1371 M e m o ra n d u m To: Members of the University Community From: Kathleen E. Schrader, Director of Student Life Date: February 4 , 1998 I am pleased to announce that Yvette Marie Flanagan will be joining the Student Life Office staff on Tuesday, February 10th as the Assistant Director of Student Life for Activities Programming. Yvette received a Bachelor of Science degree in Rehabilitation Services from Virginia Commonwealth University and a Master of Arts in Student Personnel Services degree from Rowan University. While at Rowan, she interned in the Alumni Office where she assisted the Coordinator of Alumni Relations and Special Events with planning the Mardi Gras '97, Autumn Nocturne, and homecoming activities. Yvette also organized Rowan's Student Alumni Connection which helped to develop mentor relationships between undergraduates and alumni. Please feel free to stop in and welcome Yvette to our community. -

Martin Luther King Jr

Martin Luther King Jr. Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist who The Reverend became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the American civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. King Martin Luther King Jr. advanced civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi. He was the son of early civil rights activist Martin Luther King Sr. King participated in and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights.[1] King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and later became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize some of the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. King helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The SCLC put into practice the tactics of nonviolent protest with some success by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were several dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.[2] FBI King in 1964 Director J. Edgar Hoover considered King a radical and made him an 1st President of the Southern Christian object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963, forward. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital Leadership Conference affairs and reported on them to government officials, and, in 1964, In office mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.[3] January 10, 1957 – April 4, 1968 On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating Preceded by Position established racial inequality through nonviolent resistance. -

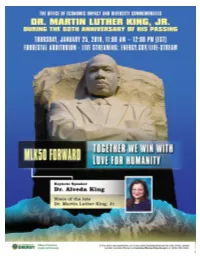

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Commemorative Program

DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. COMMEMORATIVE PROGRAM MLK50 FORWARD Together We Win With Love For Humanity January 25, 2018, 11:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. Mistress of Ceremonies Ann Augustyn Principal Deputy Director Office of Economic Impact and Diversity National Anthem Virginia Union University Choir Virginia Union University Welcome Remarks Dan Brouillette Deputy Secretary, Department of Energy Introduction of Dan Brouillette Keynote Speaker Deputy Secretary, Department of Energy Keynote Speaker Dr. Alveda King Alveda King Ministries Musical Performance Virginia Union University Choir Virginia Union University Video MLK50: Reflections from the Mountaintop Video Closing Remarks Patricia Zarate Acting Deputy Director Office of Civil Rights and Equal Opportunity “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands in times of challenge and controversy.” — Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. LIFT EVERY VOICE AND SING (James Weldon Johnson, 1871 – 1938) Lift ev’ry voice and sing, Till Earth and Heaven ring. Ring with the harmonies of Liberty; Let our rejoicing rise, High as the list’ning skies, Let it resound loud as the rolling sea. Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us, Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us; Facing the rising sun of our new day begun, Let us march on till victory is won. Stony the road we trod, Bitter the chast’ning rod, Felt in the day that hope unborn had died; Yet with a steady beat, Have not our weary feet, Come to the place for which our fathers sighed? We have come, over a way that with tears has been watered, We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered, Out from the gloomy past, Here now we stand at last Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast. -

Remarks at a Martin Luther King, Jr., Holiday Celebration January 21, 2002

Jan. 19 / Administration of George W. Bush, 2002 NOTE: The address was recorded at 1:32 p.m. The transcript was made available by the Of- on January 18 in the Cabinet Room at the fice of the Press Secretary on January 18 but White House for broadcast at 10:06 a.m. on was embargoed for release until the broad- January 19. In his remarks, the President re- cast. The Office of the Press Secretary also ferred to Title I of the Improving America’s released a Spanish language transcript of this Schools Act of 1994 (Public Law 103–382), address. The Martin Luther King, Jr., Fed- which amended Title I of the Elementary eral Holiday proclamation of January 17 is and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (Public listed in Appendix D at the end of this vol- Law 89–10); and the Individuals with Dis- ume. abilities Education Act (Public Law 94–142). Remarks at a Martin Luther King, Jr., Holiday Celebration January 21, 2002 Well, thank you all very much for com- I appreciate all the members of my team ing. Mrs. King, thanks for this beautiful who are here, in particular, Condoleezza portrait. I can’t wait to hang it. [Laughter] Rice, the National Security Adviser. Thank I want to welcome you all to the White you for coming, Condi. It’s good to see House. We’ve gathered in tribute to Dr. the Mayor. Mr. Mayor and the first lady, Martin Luther King, Jr., to the ideals he Diane, are with us today. Thank you all held and the life he lived. -

Does Emperical Evidence on the Civil Justice System Produce Or Resolve Conflict?

DePaul Law Review Volume 65 Issue 2 Winter 2016 Twenty-First Annual Clifford Symposium on Tort Law and Social Article 13 Policy Does Emperical Evidence on the Civil Justice System Produce or Resolve Conflict? Jeffrey J. Rachlinksi Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey J. Rachlinksi, Does Emperical Evidence on the Civil Justice System Produce or Resolve Conflict?, 65 DePaul L. Rev. (2016) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol65/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\D\DPL\65-2\DPL205.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-AUG-16 9:51 DOES EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE ON THE CIVIL JUSTICE SYSTEM PRODUCE OR RESOLVE CONFLICT? Jeffrey J. Rachlinski* INTRODUCTION Is the current United States Supreme Court an excessively pro-busi- ness court? The case that it is can and has been made.1 Businesses complained about punitive damage awards and the Court created con- stitutional judicial review of jury awards.2 Businesses complained about pleading rules that make it easy for consumers to bring lawsuits against business practices and the Court created heightened pleading standards.3 Businesses complained about class actions and jury trials and the Court embraced arbitration clauses, even to the point of pre- empting state law.4 Business interests, indeed, seem to be on a roll in front of the Court. -

Imagining Gun Control in America: Understanding the Remainder Problem Article and Essay Nicholas J

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2008 Imagining Gun Control in America: Understanding the Remainder Problem Article and Essay Nicholas J. Johnson Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, and the Second Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Nicholas J. Johnson, Imagining Gun Control in America: Understanding the Remainder Problem Article and Essay, 43 Wake Forest L. Rev. 837 (2008) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/439 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGINING GUN CONTROL IN AMERICA: UNDERSTANDING THE REMAINDER PROBLEM Nicholas J. Johnson* INTRODUCTION Gun control in the United States generally has meant some type of supply regulation. Some rules are uncontroversial like user- targeted restrictions that define the untrustworthy and prohibit them from accessing the legitimate supply.' Some have been very controversial like the District of Columbia's recently overturned law prohibiting essentially the entire population from possessing firearms.! Other contentious restrictions have focused on particular types of guns-e.g., the now expired Federal Assault Weapons Ban.' Some laws, like one-gun-a-month,4 target straw purchases but also constrict overall supply. Various other supply restrictions operate at the state and local level.