Bank Crimes in Indiana, 1925-1933

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crown Hill Cemetery Notables - Sorted by Last Name

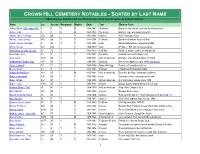

CROWN HILL CEMETERY NOTABLES - SORTED BY LAST NAME Most of these notables are included on one of our historic tours, as indicated below. Name Lot Section Monument Marker Dates Tour Claim to Fame Achey, David (Dad, see p 440) 7 5 N N 1838-1861 Skeletons Gambler who met his “just end” when murdered Achey, John 7 5 N N 1840-1879 Skeletons Gambler who was hung for murder Adams, Alice Vonnegut 453 66 Y 1917-1958 Authors Kurt Vonnegut’s sister Adams, Justus (more) 115 36 Y Y 1841-1904 Politician Speaker of Indiana House of Rep. Allison, James (mansion) 2 23 Y Y 1872-1928 Auto Allison Engineering, co-founder of IMS Amick, George 723 235 Y 1924-1959 Auto 2nd place 1958 500, died at Daytona Armentrout, Lt. Com. George 12 12 Y 1822-1875 Civil War Naval Lt., marble anchor on monument Armstrong, John 10 5 Y Y 1811-1902 Founders Had farm across Michigan road Artis, Lionel 1525 98 Y 1895-1971 African American Manager of Lockfield Gardens 1937-69 Aufderheide’s Family, May 107 42 Y Y 1888-1972 Musician She wrote ragtime in early 1900s (her music) Ayres, Lyman S 19 11 Y Y 1824-1896 Names/Heritage Founder of department stores Bacon, Hiram 43 3 Y 1801-1881 Heritage Underground RR stop in Indpls Bagby, Robert Bruce 143 27 N 1847-1903 African American Ex-slave, principal, newspaper publisher Baker, Cannonball 150 60 Y Y 1882-1960 Auto Set many cross-country speed records Baker, Emma 822 37 Y 1885-1934 African American City’s first black female police 1918 Baker, Jason 1708 97 Y 1976-2001 Heroes Marion County Deputy killed in line of duty Baldwin, Robert “Tiny” 11 41 Y 1904-1959 African American Negro Nat’l League 1920s Ball, Randall 745 96 Y 1891-1945 Heroes Fireman died on duty Ballard, Granville Mellen 30 42 Y 1833-1926 Authors Poet, at CHC ded. -

Advancing Corrections

| 1 technology re-entry leadership Advancing Corrections 2011 Annual Report INDIANA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION Leadership from the top 2 | Governor Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr. “For the Indiana Department of Correction, public safety is always the highest priority and the continual trend of lowering recidivism rates and assuring successful re-entry is critical to that mission. In 2011, the leadership and staff throughout the state have reason to be proud after receiving the coveted ACA’s Golden Eagle Award for the accreditation of all our correctional facilities. I want to commend IDOC for its continued excellence in its service to our state, while finding ways to spend tax dollars more efficiently and effectively.” Table of Contents • Letter from the Commissioner 5 • Executive Staff 6 • Timeline of Progress 18 • Adult Programs & Facilities 30 • Division of Youth Services (DYS) 48 Juvenile Programs & Facilities • Parole Services 58 • Correctional Training Institute (CTI) 66 • PEN Products 70 • Financials & Statistics 76 | 3 Vision As the model of public safety, the Indiana Department of Correction returns productive citizens to our communities and supports a culture of inspiration, collaboration, and achievement. Mission The Indiana Department of Correction advances public safety and successful re-entry through dynamic supervision, programming, and partnerships. Advancing Letter from the Commissioner through Leadership... Bruce Lemmon Commissioner Amanda Copeland Chief of Staff Penny Adams Executive Assistant Aaron Garner Executive Director -

Aug. 22-28, 2019

THIS WEEK on the WEB Roncalli football field renamed in honor of longtime high school educator Page 2 BEECH GROVE • CENTER GROVE • GARFIELD PARK & FOUNTAIN SQUARE • GREENWOOD • SOUTHPORT • FRANKLIN & PERRY TOWNSHIPS FREE • Week of August 22-28, 2019 Serving the Southside Since 1928 ss-times.com PAGES 6-7 TIMESOGRAPHY Greenwood’s WAMMfest raises $10,000 for local organizations PAGE 4 A safe place to learn Perry Meridian senior creates one-of-a-kind sensory room for students with special needs HAUNTS & JAUNTS FEATURE FEATURE FEATURE Is there a different body Greenwood solider Greenwood band hosts concert Free family entertainment in John Dillinger’s grave? killed in Ft. Hood, TX of 100s of statewide musicians at BG’s Music on Main Page 5 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 SEE OUR AD ON PAGE 5 Altenheim (Indianapolis/Beech Grove) I am so happy with dad’s care Aspen Trace (Greenwood/Bargersville/Center Grove) and how content he seems. Greenwood Health & Living University Heights Health & Living (Indianapolis/Greenwood) I agree I’m so grateful for CarDon! www.CarDon.us CARDON - EXPERT SENIOR LIVING SOLUTIONS. 2 Week of August 22-28, 2019 • ss-times.com COMMUNITY The Southside Times Contact the Southside THIS Managing Editor on the Have any news tips? Want News Quiz WEEK to submit a calendar event? WEB Have a photograph to share? Call Nancy Price at How well do you know your 698-1661 or email her at Southside community? Roncalli to dedicate Kranowitz named [email protected]. And remember, our news Test your current event football field to Bob Tully president and CEO of Keep deadlines are several days prior to print. -

Legislature a Shallow Talent Pool Former Gov

V14 N43 Thursday, July 9, 2009 Legislature a shallow talent pool Former Gov. Oxley’s painful fall Edgar Whit- underscores shift away comb (left) and U.S. Sen. Evan from Statehouse for Bayh at the Statehouse dur- gubernatorial timber ing Gov. Frank O’Bannon’s By BRIAN A. HOWEY funeral in 2003. INDIANAPOLIS - The sad The two repre- story about the fall of 2008 Demo- sent contrasting cratic lieutenant governor nominee eras when the Dennie Oxley II since February un- Indiana General derscores an emerging Assembly was trend when it comes a gubernato- to power politics: rial breeding The Indiana General ground. (HPI Assembly is losing its Photo by Brian station as a breeding A. Howey) ground for guberna- torial tickets. When Democratic gubernato- 1996 won the rial nominee Jill Long Thompson won the primary in May nominations, with roots going back to the Indiana Senate. 2008, it was the eighth time out of the last 10 nomination In that time frame, the two major parties have slots that went to an individual who didn’t have roots in the relied on two mayors, a congressman, a former congress- Indiana General Assembly. The two exceptions occurred when Lt. Gov. John Mutz in 1988 and Frank O’Bannon in Continued on Page 3 Kenny Rogers session By DAVE KITCHELL LOGANSPORT - Collectively, 151 people played out their hands last Tuesday in the Indiana Statehouse. In the end, they all left with something, which after all is the goal of any card player when they leave the table. “I’m looking forward to maybe Gov. -

**** This Is an EXTERNAL Email. Exercise Caution. DO NOT Open Attachments Or Click Links from Unknown Senders Or Unexpected Email

Scott.A.Milkey From: Hudson, MK <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, June 20, 2016 3:23 PM To: Powell, David N;Landis, Larry (llandis@ );candacebacker@ ;Miller, Daniel R;Cozad, Sara;McCaffrey, Steve;Moore, Kevin B;[email protected];Mason, Derrick;Creason, Steve;Light, Matt ([email protected]);Steuerwald, Greg;Trent Glass;Brady, Linda;Murtaugh, David;Seigel, Jane;Lanham, Julie (COA);Lemmon, Bruce;Spitzer, Mark;Cunningham, Chris;McCoy, Cindy;[email protected];Weber, Jennifer;Bauer, Jenny;Goodman, Michelle;Bergacs, Jamie;Hensley, Angie;Long, Chad;Haver, Diane;Thompson, Lisa;Williams, Dave;Chad Lewis;[email protected];Andrew Cullen;David, Steven;Knox, Sandy;Luce, Steve;Karns, Allison;Hill, John (GOV);Mimi Carter;Smith, Connie S;Hensley, Angie;Mains, Diane;Dolan, Kathryn Subject: Indiana EBDM - June 22, 2016 Meeting Agenda Attachments: June 22, 2016 Agenda.docx; Indiana Collaborates to Improve Its Justice System.docx **** This is an EXTERNAL email. Exercise caution. DO NOT open attachments or click links from unknown senders or unexpected email. **** Dear Indiana EBDM team members – A reminder that the Indiana EBDM Policy Team is scheduled to meet this Wednesday, June 22 from 9:00 am – 4:00 pm at IJC. At your earliest convenience, please let me know if you plan to attend the meeting. Attached is the meeting agenda. Please note that we have a full agenda as this is the team’s final Phase V meeting. We have much to discuss as we prepare the state’s application for Phase VI. We will serve box lunches at about noon so we can make the most of our time together. -

The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde by David Edmondson

The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde By David Edmondson D-LAB FILMS First Draft July 2012 Second Draft August 2012 Third Draft August 2012 EXT. TEXAS HIGHWAY--NIGHT Pitch black night broken by the headlight of a 1932 Ford V8 Coupe screaming down a secluded Texas highway. INT. FORD--CONTINUED Three people are crammed into the small Ford along with an arsenal. In the back seat W.D. JONES (17) he is curled asleep on the back bench. In the front seat BONNIE PARKER (22) is asleep on the shoulder of her lover CLYDE BARROW (23) who is driving at near light speed. The Ford’s headlights dimly light the road making it truly hard to see what is out there. Clyde passes a bridge out sign. Suddenly... EXT. BRIDGE--CONTINUED the Ford crashes through the road block--it instantly launched into the air. It comes smashing down rolling three times--the Ford is destroyed but standing upright. The Ford’s fuel line has become split--it is leaking fuel. The cable has come loose from the battery. All three passengers are knocked out. Clyde first to awake gets out of the car--blood running down his nose. He stumbles around trying to gain conciseness. He pulls W.D. out from the wreckage--returning to get Bonnie next. W.D. awakens--he is at Clyde’s side helping to pull Bonnie from the car. Then... a spark from the loose battery cord starts a fire. Flames begin to cover the hood. W.D. starts to kick dirt on the fire--it doesn’t help. -

Fimp P *2.22 *244

PAGE 6 THE INDIANAPOLIS TIMES JAN. 5, It* STORY OF JOHN DILLINGER'S BOYHOOD IS TOLD BY THESE PHOTOS CITIZEN-OWNED' UTILITY PLANTS £ I SHOW PROFIT Municipal Light and Power . Plants in ’32 Made ' $212,542.10, Municipally owned utilities re- turned a net profit of $212,542.10 to Indiana towns where they operate and thus aided in keeping them I JEFTr JmmF^aaSg from borrowing from working bal- ances in 1932. This fact is set out in a report on town finances for that year made public today by William P. Cos- grove. ...... state examiner. It was pre- ' ' pared in his office by Albert E. Dickens, statistician. One hundred and forty-two civil towns operate ,waterworks, fifty- three electric plants and thirty both water and electric utilities, the re- port shows. In 1932. these utilities received 51.023.6C7.50 in operating revenues and disbursed 5811.065.40 for oper- ating and maintenance. Expenses Decrease In the total of 423 Indiana towns, the governmental cost for 1932 was $3,461,003.47, the reiiort shows. This was $593,623.52 or 14.6 per cent less than was expended in 1931. Tax re- ceipts were 26.4 per cent less, how- ever, being the lowest since 1922. CAPITOL They decreased 21.4 per cent from Suits, Topcoats, Overcoats 1 the previous year and were $253.- 1 006.39 less than disbursements, ne- cessitating inroads on working bal- ances to make up the deficiency in revenue. School functions were maintained in but eighty of the incorporated towns at a cost of $2,101,915. -

Bonnie and Clyde: the Making of a Legend by Karen Blumenthal, 2018, Viking Books for Young Readers

Discussion and Activity Guide Bonnie and Clyde: The Making of a Legend by Karen Blumenthal, 2018, Viking Books for Young Readers BOOK SYNOPSIS “Karen Blumenthal’s breathtaking true tale of love, crime, and murder traces Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow’s wild path from dirt-poor Dallas teens to their astonishingly violent end and the complicated legacy that survives them both. This is an impeccably researched, captivating portrait of an infamous couple, the unforgivable choices they made, and their complicated legacy.” (publisher’s description from the book jacket) ABOUT KAREN BLUMENTHAL “Ole Golly told me if I was going to be a writer I better write down everything … so I’m a spy that writes down everything.” —Harriet the Spy, Louise Fitzhugh Like Harriet M. Welsch, the title character in Harriet the Spy, award-winning author Karen Blumenthal is an observer of the world around her. In fact, she credits the reading of Harriet the Spy as a child with providing her the impetus to capture what was happening in the world around her and become a writer herself. Like most authors, Blumenthal was first a reader and an observer. She frequented the public library as a child and devoured books by Louise Fitzhugh and Beverly Cleary. She says as a child she was a “nerdy obnoxious kid with glasses” who became a “nerdy obnoxious kid with contacts” as a teen. She also loved sports and her hometown Dallas sports teams as a kid and, consequently, read books by sports writer, Matt Christopher, who inspired her to want to be a sports writer when she grew up. -

TEXAS RANGER DISPATCH Magazine-Captain L. H. Mcnelly

Official State Historical Center of the Texas Rangers law enforcement agency. The Following Article was Originally Published in the Texas Ranger Dispatch Magazine The Texas Ranger Dispatch was published by the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum from 2000 to 2011. It has been superseded by this online archive of Texas Ranger history. Managing Editors Robert Nieman 2000-2009; (b.1947-d.2009) Byron A. Johnson 2009-2011 Publisher & Website Administrator Byron A. Johnson 2000-2011 Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame Technical Editor, Layout, and Design Pam S. Baird Funded in part by grants from the Texas Ranger Association Foundation Copyright 2017, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, TX. All rights reserved. Non-profit personal and educational use only; commercial reprinting, redistribution, reposting or charge-for- access is prohibited. For further information contact: Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, PO Box 2570, Waco TX 76702-2570. TEXAS RANGER DISPATCH Magazine-Clyde Barrrow and Bonnie Parker Rangers Today Visitor Info History Research Center Hall of Fame Student Help Family History News Click Here for Now You Know: A Complete Index to All Back Issues Dispatch Home Visit our nonprofit Museum Store! Contact the Editor Encounter with Clyde Barrrow and Bonnie Parker Ask any Ranger who knew him and he will tell you that Bennie Krueger was one of the best Rangers who ever lived and one of the finest men he ever knew. But few know this story—a tale that could have ended in death for Bennie. It was a cold fall evening in 1933 and Bennie was working as a police officer on the Brenham (Texas) Police Department. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that. -

Case Study – Forensic Science Dillinger Death Mask

Case Study – Forensic Science Dillinger Death Mask by Professor D.E. Ashworth of Worsham mold that adhered to the plaster surface At a Glance College of Embalming, pictured below. and was later removed for analysis. McCrone Associates examined a Two masks were cast by Harold N. May plaster cast containing a rubber of the Reliance Dental Manufacturing The rubber mask was gently removed mask that was purported to be Company; one was sent to the FBI, and from the plaster cast, and the interior cast from John Dillinger’s face at the other was retained by May. details of the plaster were examined the time of his death. with the unaided eye and moderate Issue magnification. The entire inner surface McCrone Associates was asked to of the rubber mask was examined examine a death mask believed to be microscopically. Situation pictured on the front page of the July 24, John Herbert Dillinger was an infamous 1933 Chicago Herald and Examiner—the Results American gangster and robber during the mask that was confiscated. The materials of construction, plaster and Depression era. Dillinger, the first criminal carbon black filled rubber, were available to be named Public Enemy Number One Solution at the time the mask was purported to by the FBI, was shot by federal agents The plaster cast was examined by two have been made. in the alley behind Chicago’s Biograph McCrone Associates scientists. The interior theater on July 22, 1934. Dillinger died of the cast was covered with black rubber instantly from a shot that entered the base of his neck, severed his spinal chord, and exited below his right eye. -

BANKS, DILLINGER and MAD DOG EARLE by Michael J

BANKS, DILLINGER AND MAD DOG EARLE By Michael J. Carroll love the print media. I may suffer from printed word Warner Brothers Hollywood of the 1930s and 40s: racism. Her neurosis, maybe even addiction. I also love print’s mother was Native American and she mentions and alludes to flashier younger media sister, film, with its vibrant discrimination suffered. and hypnotic images of society – of us. I await the Unlike the love of the aloof Bogart, Depp is madly in love Ipictures of banks, law, and life that will spring from with his girl and knows it immediately. Like Bogart’s Duke our chaotic economic times. Mantee of “The Petrified Forest,” the earlier gangster film that “Public Enemies,” which starred Johnny Depp as the helped make his career, Bogart/Earle thinks that a “dame” is Depression-era gangster John Dillinger, helped me remember something that weighs you down, slows you down, makes you one of my gangster favorites, the old B movie classic, “High soft and allows the cops to catch up to you. Maybe Mad Dog Sierra,” which featured Humphrey Bogart as gangster Roy Earle has a point that cannot be dismissed completely since Earle (a.k.a. Mad Dog Earle), a the Feds in both films track and thinly disguised John Dillinger. trap men through women. “High Sierra” was filmed while Some of the “lawmen” are Dillinger’s life, bank-robbing recognizable in both films. rampage, and death were still Depp’s FBI lawmen go off fresh in the collective American in a new “modern” direction: memory. Bogart portrayed him He disdains the suit- scientific, bureaucratic and as a sympathetic Midwestern seeking publicity.