The Dramaturgy of Italian Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Minnesota Opera’S Production of La Traviata

The famous Brindisi in Minnesota Opera’s production of La Traviata. Photo by Dan Norman What can museums learn about attracting new audiences from Minnesota Opera? Summary Someone Who Speaks Their Language: How a Nontraditional Partner Brought New Audiences to Minneso- ta Opera is part of a series of case studies commissioned by The Wallace Foundation to explore arts and cultural organizations’ evidence-based efforts to reach new audiences and deepen relationships with their existing audiences. Each aspires to capture broadly applicable lessons about what works and what does not—and why—in building audiences. The American Alliance of Museums developed this overview to high- light the relevance of the case study for museums and promote cross-sector learning. The study tells the story of how one arts organization brought thousands of new visitors to its programs by partnering with an unconventional spokesperson. Minnesota Opera’s approach to reaching new audiences with messages that spoke to their interests is applicable to any museum looking to build new audiences. Challenge Like many organizations dedicated to traditional art forms, Minnesota Opera’s audience was “graying,” with patrons over sixty making up about half of its audience. While this older audience was loyal, and existing programs for young audiences showed promise, there was a gap for middle-aged people in between the ends of this spectrum. Audience Goal The Opera decided to reach out to women between the ages of thirty-five and sixty, because this demo- graphic showed unactualized potential in attendance data. They wanted to bust stereotypes that opera is a stagnant and irrelevant art form. -

JOHN HANCOCK Baritone

JOHN HANCOCK Baritone Acclaimed for his refined vocalism and theatrical versatility, baritone John Hancock made his Metropolitan Opera debut as le Gendarme in Les Mamelles de Tirésias under the baton of James Levine. He has since appeared in a dozen roles with the company, including: Count Almaviva in Le nozze di Figaro, Falke in Die Fledermaus, Albert in Werther, Brétigny in Manon, Capulet in Roméo et Juliette, and both Marcello and Schaunard in La bohème. At San Francisco Opera, he sang the roles of Sharpless in Madama Butterfly, Yeletsky in Queen of Spades, and Lescaut in Manon Lescaut. New York City Opera audiences have heard him in numerous productions, including Capriccio, Carmina Burana, and Le Nozze di Figaro. He has also sung leading roles with companies including Washington National Opera, New Israeli Opera, Opéra du Rhin, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, and Cincinnati Opera. A gifted interpreter of contemporary opera, John Hancock has created leading roles in several world premieres, notably Lowell Liebermann’s The Picture of Dorian Gray at Opéra de Monte Carlo, Stephen Paulus’s Heloise and Abelard as an alumni artist at the Juilliard School, and Central Park, a trilogy of American operas, at Glimmerglass Opera and New York City Opera (also broadcast on PBS Great Performances). Of his performance in Pascal Dusapin’s Faustus, the Last Night at the Spoleto Festival USA, The New York Times wrote, “John Hancock was particularly strong in the title role, seizing every opportunity to soar.” Other notable performances in recent seasons include Ramiro in l’Heure espagnole with Seiji Ozawa’s Veroza Opera Japan, the title role in Eugene Onegin at Opera Ireland, and John Buchanan in Lee Hoiby’s Summer and Smoke at Central City Opera. -

Towards a Cultural History of Italian Oratorio Around 1700: Circulations, Contexts, and Comparisons

This is a working paper with minimal footnotes that was not written towards publication—at least not in its present form. Rather, it aims to provide some of the wider historiographical and methodological background for the specific (book) project I am working on at the Italian Academy. Please do not circulate this paper further or quote it without prior written consent. Huub van der Linden, 1 November 2013. Towards a cultural history of Italian oratorio around 1700: Circulations, contexts, and comparisons Huub van der Linden “Parlare e scrivere di musica implica sempre una storia degli ascolti possibili.” Luciano Berio, Intervista sulla musica (1981) 1. Oratorio around 1700: Historiographical issues since 1900 In the years around 1900, one Italian composer was hailed both in Italy and abroad as the future of Italian sacred music. Nowadays almost no one has heard of him. It was Don Lorenzo Perosi (1872-1956), the director of the Sistine Chapel. He was widely seen as one of the most promising new composers in Italy, to such a degree that the Italian press spoke of il momento perosiano (“the Perosian moment”) and that his oratorios appeared to usher in a new flourishing of the genre.1 His oratorios were performed all over Europe as well as in the USA, and received wide-spread attention in the press and music magazines. They also gave rise to the modern historiography of the genre. Like all historiography, that of Italian oratorio is shaped by its own historical context, and like all writing about music, it is related also to music making. -

Music on Stage

Music on Stage Music on Stage Edited by Fiona Jane Schopf Music on Stage Edited by Fiona Jane Schopf This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Fiona Jane Schopf and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7603-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7603-2 TO SUE HUNT - THANK YOU FOR YOUR WISE COUNSEL TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ...................................................................................... x List of Tables .............................................................................................. xi Foreword ................................................................................................... xii Acknowledgments .................................................................................... xiii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Opera, the Musical and Performance Practice Jane Schopf Part I: Opera Chapter One ................................................................................................. 8 Werktreue and Regieoper Daniel Meyer-Dinkgräfe -

The Baritone Voice in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: a Brief Examination of Its Development and Its Use in Handel’S Messiah

THE BARITONE VOICE IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND ITS USE IN HANDEL’S MESSIAH BY JOSHUA MARKLEY Submitted to the graduate degree program in The School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Stephens ________________________________ Dr. Michelle Hayes ________________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ________________________________ Dr. Julia Broxholm ________________________________ Mr. Mark Ferrell Date Defended: 06/08/2016 The Dissertation Committee for JOSHUA MARKLEY certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE BARITONE VOICE IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND ITS USE IN HANDEL’S MESSIAH ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Stephens Date approved: 06/08/2016 ii Abstract Musicians who want to perform Handel’s oratorios in the twenty-first century are faced with several choices. One such choice is whether or not to use the baritone voice, and in what way is best to use him. In order to best answer that question, this study first examines the history of the baritone voice type, the historical context of Handel’s life and compositional style, and performing practices from the baroque era. It then applies that information to a case study of a representative sample of Handel’s solo oratorio literature. Using selections from Messiah this study charts the advantages and disadvantages of having a baritone sing the solo parts of Messiah rather than the voice part listed, i.e. tenor or bass, in both a modern performance and an historically-informed performance in an attempt to determine whether a baritone should sing the tenor roles or bass roles and in what context. -

Eighteenth-Century Reception of Italian Opera in London

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2013 Eighteenth-century reception of Italian opera in London. Kaylyn Kinder University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Kinder, Kaylyn, "Eighteenth-century reception of Italian opera in London." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 753. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/753 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY RECEPTION OF ITALIAN OPERA IN LONDON By Kaylyn Kinder B.M., Southeast Missouri State University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Division of Music History of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Department of Music University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2013 EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY RECEPTION OF ITALIAN OPERA IN LONDON By Kaylyn Kinder B.M., Southeast Missouri State University, 2009 A Thesis Approved on July 18, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Jack Ashworth, Thesis Director Douglas Shadle Daniel Weeks ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Jack Ashworth, for his guidance and patience over the past two years. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. -

Inventing Opera As “High Culture”

For many people opera represents (whether this is understood posi- tively or negatively) the very embodiment of “high culture.”Yet lately there have been signs that its status is changing, as opera becomes more and more a feature of everyday cultural life.1 What I want to explore in this chapter is whether these changes have now made it possible to describe opera as popular culture. Inventing Opera as “High Culture” In order to fully understand what has been happening to opera in recent years, I think it is first necessary to examine something of the history of opera. Traditionally, opera is said to have been invented in the late sixteenth century by a group of Florentine intellectuals known as the Camerata.2 However, according to musicologist Susan McClary, Despite the humanistic red herrings proffered by Peri, Caccini [members of the Camerata], and others to the effect that they were reviving Greek performance practices, these gentlemen knew very well that they were basing their new reciting style on the improvisatory practices of con- temporary popular music. Thus the eagerness with which the humanist myth was constructed and elaborated sought both to conceal the vulgar origins of its techniques and to flatter the erudition of its cultivated patrons. (McClary, 1985: 154–5) Although there may be some dispute over the intellectual origins of opera, there is general agreement about its commercial beginnings. “Expecting Rain”: Opera as Popular Culture? 33 Significantly, the opera house was the “first musical institution to open its doors to the general public” (Zelochow, 1993: 261). The first opera house opened in Venice in 1637: it presented “commercial opera run for profit . -

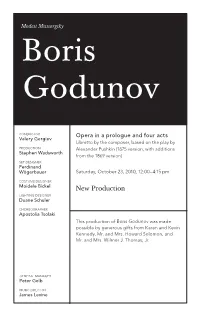

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Richard STRAUSS Intermezzo Elisabeth Söderström

RICHARD STRAUSS INTERMEZZO Elisabeth Söderström Glyndebourne Festival Opera London Philharmonic Orchestra Sir John Pritchard RICHARD STRAUSS © SZ Photo/Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Richard Strauss (1864 –1949) Intermezzo A bourgeois comedy with symphonic interludes in two acts Libretto by the composer English translation by Andrew Porter Christine Elisabeth Söderström soprano Robert Storch, her husband, a conductor Marco Bakker baritone Anna, their maid Elizabeth Gale soprano Franzl, their eight-year-old son Richard Allfrey spoken Baron Lummer Alexander Oliver tenor The Notary Thomas Lawlor bass-baritone His wife Rae Woodland soprano Stroh, another conductor Anthony Rolfe Johnson tenor A Commercial Counsellor Donald Bell Robert’s Skat baritone partners A Legal Counsellor Brian Donlan baritone { A Singer Dennis Wicks bass Fanny, the Storchs’ cook Barbara Dix spoken Marie, a maid Susan Varley spoken Therese, a maid Angela Whittingham spoken Resi, a young girl Cynthia Buchan soprano Glyndebourne Festival Opera London Philharmonic Orchestra Sir John Pritchard 3 compact disc one Time Page Act I Scene 1 1 ‘Anna, Anna! Where can the silly creature be?’ 5:52 [p.28] The Wife, the Husband, Anna 2 ‘Have you got all the master’s things?’ 6:02 [p.32] The Wife, Anna, the Husband 3 ‘And now I’ll have my hair done!’ 11:16 [p.35] The Wife, Anna, The Son, Housemaid, Cook 4 'Oh! Frau Huß! Good morning' 2:59 [p.39] The Wife, Anna Scene 2 5 ‘You blockhead! Can’t you see, this is a toboggan run?’ 4:08 [p.39] The Wife, Baron Lummer 6 Waltz 1:55 [p.40] -

![12. Comic Intermezzo [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2033/12-comic-intermezzo-pdf-1582033.webp)

12. Comic Intermezzo [PDF]

COMIC INTERMEZZO INTERMEZZI are comic 2-act interludes sung between the 3 acts of an opera seria Intermezzi originate from the Renaissance INTERMEDIO, the musical numbers sung between acts of a spoken theatrical play COMIC INTERMEZZO In their original form an INTERMEZZO was composed for an OPERA SERIA and was thematically related to the main opera. COMIC INTERMEZZO COMIC INTERMEZZO Pergolesi’s two-act La Serva Padrona, was performed between the three acts of his opera seria, Il Prigioner Superbo in 1733. COMIC INTERMEZZO The traditions of Commedia dell’Arte, Italian improvised comic theater, serve as models for character types and plots in the intermezzo 1725-1750! “Golden Age” of Intermezzo COMMEDIA dell’ARTE ARLECCHINO Probably the most famous of Commedia characters, Arlecchino is a good-hearted and well-intentioned buffoon. He can be crafty and clever, but is never malicious. COMMEDIA dell’ARTE COLOMBINA is a clever female servant with a keen and active wit and able to hold her own in every situation and emerge triumphant from the most complicated intrigues. A country girl, she takes a frank attitude towards men and sex. COMMEDIA dell’ARTE PANTALONE The Old Man, often a rich miser, though he pretends to poverty. He suspects everyone of trying to dupe him (he is usually right) even as he plans his own schemes. COMMEDIA dell’ARTE CAPITANO is a swaggering braggart soldier, usually foreign (and sometimes pretending to be of noble blood). Capitano boasts of great prowess at both love and war, but is in reality an abject failure at both. COMIC INTERMEZZO Giovanni Battista PERGOLESI (1710-1736) Writes intermezzo La Serva Padrona in 1733 COMIC INTERMEZZO LA SERVA PADRONA [The Maid Mistress] “Intermezzo Buffo in Due Atti” (1733) Libretto by G. -

EJ Full Draft**

Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy By Edward Lee Jacobson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfacation of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair Professor James Q. Davies Professor Ian Duncan Professor Nicholas Mathew Summer 2020 Abstract Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy by Edward Lee Jacobson Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair This dissertation emerged out of an archival study of Italian opera libretti published between 1800 and 1835. Many of these libretti, in contrast to their eighteenth- century counterparts, contain lengthy historical introductions, extended scenic descriptions, anthropological footnotes, and even bibliographies, all of which suggest that many operas depended on the absorption of a printed text to inflect or supplement the spectacle onstage. This dissertation thus explores how literature— and, specifically, the act of reading—shaped the composition and early reception of works by Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and their contemporaries. Rather than offering a straightforward comparative study between literary and musical texts, the various chapters track the often elusive ways that literature and music commingle in the consumption of opera by exploring a series of modes through which Italians engaged with their national past. In doing so, the dissertation follows recent, anthropologically inspired studies that have focused on spectatorship, embodiment, and attention. But while these chapters attempt to reconstruct the perceptive filters that educated classes would have brought to the opera, they also reject the historicist fantasy that spectator experience can ever be recovered, arguing instead that great rewards can be found in a sympathetic hearing of music as it appears to us today.