20171229134946991 12-29-17 Harkness V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DARK BAY OR BROWN FILLY Barn 5 Hip No. 1427

Consigned by Denali Stud, Agent XXXIV Barn DARK BAY OR BROWN FILLY Hip No. 5 Foaled February 26, 2019 1427 Indian Charlie Uncle Mo .............................. Playa Maya Nyquist .................................. Forestry Seeking Gabrielle .................. Seeking Regina DARK BAY OR Empire Maker BROWN FILLY Pioneerof the Nile ................ Star of Goshen Lady Bling ............................ (2012) Kris S. Spangled .............................. Bangled By NYQUIST (2013). Champion 2-year-old, classic winner of 8 races at 2 and 3, $5,189,200, Kentucky Derby [G1] (CD, $1,631,600), Breeders' Cup Ju - venile [G1] (KEE, $1,100,000), Xpressbet.com Florida Derby [G1] (GP, $1,589,000), FrontRunner S. [G1] (SA, $180,000), Del Mar Futurity [G1] (DMR, $180,000), Best Pal S. [G2] (DMR, $120,000), San Vicente S. [G2] (SA, $120,000), 3rd Preakness S. [G1] (PIM, $165,000). His first foals are 2-year-olds of 2020 . Sire of Breakthrough (placed in 2 starts, $19,800). 1st dam LADY BLING, by Pioneerof the Nile. Winner at 2, 3, and 4, $118,664. Dam of 1 other registered foal, a 2-year-old of 2020, which has not started. 2nd dam SPANGLED , by Kris S. Winner at 2 and 3, 33,700, in France, Criterium de Lyon [L]; winner at 4, $36,400, in N.A./U€.S. (Total: $70,285). Dam of-- Spangled Star (g. by Distorted Humor). 3 wins at 3 and 4, $100,620, 3rd Withers S. [G3] (AQU, $15,000). 3rd dam BANGLED, by Alysheba. Unraced. Half-sister to GRECIAN FLIGHT [G1] ($1,- 320,215), GRECIAN COMEDY -L, EVZONE -L. Dam of 6 winners, incl.-- ANKLET . -

Nyquist Gains Victory at the 142Nd Kentucky Derby Swiss Watchmaking Brand Longines Celebrates Winner As the Official Timekeeper and Watch of the Triple Crown

Press release Nyquist Gains Victory at the 142nd Kentucky Derby Swiss Watchmaking Brand Longines celebrates winner as the Official Timekeeper and Watch of the Triple Crown LOUISVILLE, Ky., May 8, 2016 – Longines, the internationally renowned Swiss watch brand and Official Timekeeper of the Triple Crown, celebrated the 142nd running of the Kentucky Derby on Saturday by awarding Nyquist, owner, trainer and jockey with elegant timepieces at the exclusive Winners’ Circle Party. As the Official Watch and Timekeeper of the Triple Crown, Longines was proud to be an integral part of the 142nd running of the Kentucky Derby and support America’s greatest race. Nyquist, ridden by Mario Gutierrez, clocked in at 2:01.31, racing past Exaggerator and Gun Runner to win the Kentucky Derby – the Most Exciting Two Minutes in Sports. Amy Figueroa, U.S Brand Manager at Longines, presented owner, trainer and jockey of Nyquist with watches from The Longines Master Collection after an incredible win. The Longines Master Collection brings together classical elegance and watchmaking expertise. All range of requirements can be satisfied by the choice of displays offered by the collection: chronograph functions, indication of time in all 24 time-zones worldwide, power- reserve indicator, phases of the moon or retrograde functions. The Longines Master Collection cases are available in steel, steel and yellow gold or 18 carat rose gold. Water- resistant to 3 bar, they also have a transparent case back through which the proud owner can admire the fascinating working of the movement. Each timepiece is mounted on a steel and yellow gold or a steel bracelet, or on a black or brown alligator strap. -

Champion Maker

MAKER CHAMPION The Toyota Blue Grass Stakes has shaped the careers of many notable Thoroughbreds 48 SPRING 2016 K KEENELAND.COM Below, the field breaks for the 2015 Toyota Blue Grass Stakes; bottom, Street Sense (center) loses a close 2007 running. MAKER Caption for photo goes here CHAMPION KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2016 49 RICK SAMUELS (BREAK), ANNE M. EBERHARDT CHAMPION MAKER 1979 TOBY MILT Spectacular Bid dominated in the 1979 Blue Grass Stakes before taking the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes. By Jennie Rees arl Nafzger’s short list of races he most send the Keeneland yearling sales into the stratosphere. But to passionately wanted to win during his Hall show the depth of the Blue Grass, consider the dozen 3-year- of Fame training career included Keeneland’s olds that lost the Blue Grass before wearing the roses: Nafzger’s Toyota Blue Grass Stakes. two champions are joined by the likes of 1941 Triple Crown C winner Whirlaway and former record-money earner Alysheba Instead, with his active trainer days winding down, he has had to (disqualified from first to third in the 1987 Blue Grass). settle for a pair of Kentucky Derby victories launched by the Toyota Then there are the Blue Grass winners that were tripped Blue Grass. Three weeks before they entrenched their names in his- up in the Derby for their legendary owners but are ensconced tory at Churchill Downs, Unbridled finished third in the 1990 Derby in racing lore and as stallions, including Calumet Farm’s Bull prep race, and in 2007 Street Sense lost it by a nose. -

DARK BAY OR BROWN COLT Barn 18 Hip No. 22

Consigned by Dromoland Farm Inc. (Gerry Dilger), Agent I Hip No. DARK BAY OR BROWN COLT Barn 22 Foaled February 8, 2019 18 Indian Charlie Uncle Mo .............................. Playa Maya Nyquist .................................. Forestry Seeking Gabrielle .................. Seeking Regina DARK BAY OR Gone West BROWN COLT Grand Slam .......................... Bright Candles Zaharias ................................ (2009) French Deputy Scarlet Tango ........................ Silver Tango By NYQUIST (2013). Champion 2-year-old, classic winner of 8 races at 2 and 3, $5,189,200, Kentucky Derby [G1] (CD, $1,631,600), Breeders' Cup Ju - venile [G1] (KEE, $1,100,000), Xpressbet.com Florida Derby [G1] (GP, $1,589,000), FrontRunner S. [G1] (SA, $180,000), Del Mar Futurity [G1] (DMR, $180,000), Best Pal S. [G2] (DMR, $120,000), San Vicente S. [G2] (SA, $120,000), 3rd Preakness S. [G1] (PIM, $165,000). His first foals are 2-year-olds of 2020 . Sire of Breakthrough (placed in 2 starts, $19,800). 1st dam ZAHARIAS, by Grand Slam. Winner at 3, $32,598. Sister to VISIONAIRE . Dam of 4 other registered foals, 4 of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2020, 3 to race, 3 winners, including-- Bodebabe (f. by Bodemeister). Winner at 3, $32,130. Hackle Setter (c. by Noble Mission (GB)). 2 wins at 2, £14,469, in England; placed at 4, 2020, 7,250, in France. (Total: $26,766). € 2nd dam Scarlet Tango , by French Deputy. 4 wins, 2 to 4, $99,493, 2nd Laura Gal S. (LRL, $8,000). Half-sister to DALE'S PROSPECT ($344,864), OUR COM - MANDER ($125,225), Bumpy Road ($95,165). -

Nyquist V. Mauclet Lewis F

Washington and Lee University School of Law Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons Supreme Court Case Files Powell Papers 10-1976 Nyquist v. Mauclet Lewis F. Powell Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/casefiles Part of the Education Law Commons, and the Fourteenth Amendment Commons ·, ,, • I_- \,, I / ) ., t} /• . ''\ I I I~ ( ;\ (.' I JI - ,I ·" , I . • , . t 1 .,. ,.,•I Q "''." 3 Ql lc..~ .,./ , ~--..,.., ..• ,.:- ..... - '\. ,"'i I_ ) l , , _, J' ., ,(J. .,._L af ., ~ - . ,. .. 1~. .-, ::9" , .. ., , ,. • , - I . ,.,, _,., ,,,.,. ,. , .. , , ..., ( . .......... I,_ .. .... -. - -~JV--,, ✓_,J ' . I' (<:;.4i <"- ... (' ' 1) • ,,. .,,. -"\_,. (' /,I'"· .. ,rJ,. ( , I _# '.' , ..,,, ,. ' ,, .0 , ~ ,I " / ?!-{_ .. ,:,_£ .: (' ( ,_") I t . i t ~ l t) ~:;; ~.,~c_ .. V--,-;~ ,. , -, ~ ' .. ct~::-: I ~~ ~-<,~~~ ~~ v-~~ , I .... ~11'"1~- I/•"··... -... ,,, ~-___,. ~ -, -C~ / /,)• C. -J . , < -$ • ( ; ) i.~., . ... ~ ;,~c:-~l ,; __ .. / . - • ,(,.J . ,-✓._,.,, , . ( , ,(..., (.,_II f ✓~.. ,'--{ < -., ..•. ,._:,_/ /'7) ,,. ,;"' ./ I i .... · ' ( ~ - .,,1: ( , ,, d' "~: .. --J.,. - '"' ... ,,. - - ~ l .. ,.. .. \._ . - ,.,. - - - /.}_ ,· '7-{, / _, ___/. / ,, PRE LT.MINAR. Y ME:\lORJ\NDUM ,.... ; I I ,I /7 ) \ • . , / I I. - "'"'1' "- - . ~- ( ·--\ / :..,... / - .. ~., ./. Octobe r 15 , 1976 Confc1~cri.cf:) • ' , . / ..4•{..,-c..,...-..,. List 1, Sheet 1 - 7 / • / .. tJ I tA c_. l I ·· "" - ../' .ti "'1 f_l, , , • ·, J ( 4 1-;· ,., ,:,; ,...,,J(,~ 4 .,,.I v ~ .. .I" . I I " .• , ~ -~ .. d'-"t ,,, J.... ".\. No . 75-1809 'ppca~ fr on.1 3 - JUDGE _.,,-:-~.-c:.. ,, ,.. / v.1. /1 ✓ JJ-'' __, DC (Van G raaieiland · / ,/ -~,,;. -1-❖ ,.: ·., ~ ) .' <)J · t C. J. , Curtin, E. D. NY; /'-<"~ .. ~ , ✓- .,_•~ J, 11 J '-~ C."· s I ,r ·• • I--\ •~it, ' \,L Iv: - ' ~..,/./' Judd , W. D . NY) /. ,;.f ,1_ / I ,. s ~ ~., .. ,.,.. ..,, · / v . (, I t.,I , v .... ' " I I I ,..v - J <' ''° ✓ I __ J' t. NYQUIST, C on~'r of Educ . -

Gretzky= Scores Another Grade I Win for Nyquist In

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2020 >GRETZKY= SCORES THE WEEK IN REVIEW: AFTER GUILTY PLEAS, WILL MORE TRAINERS BE CHARGED? ANOTHER GRADE I WIN by Bill Finley The next chapter in the scandal that has rocked Thoroughbred FOR NYQUIST IN SUMMER racing played out last week when Scott Robinson and Sarah Izhaki both pled guilty to charges relating to the sale and distribution of performance-enhancing drugs used to dope race horses. It was an important development, but the bigger story is this: will it lead to a new and extensive list of indictments against trainers and others who so far have not been charged? That possibility certainly exists. For now, everything is speculation and the Department of Justice has not said whether or not Izhaki and Robinson are cooperating in the probe, but it's not hard to connect the dots and come up with a scenario where the two are cooperating with authorities and ready to name names. Cont. p11 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY IRISH YEARLING SEASON BEGINS IN NEWMARKET Gretzky the Great | Michael Burns The Tattersalls Ireland September Yearling Sale kicks off on Monday and Daithi Harvey has the preview. Click or tap here Gretzky the Great (Nyquist), who became freshman sire to go straight to TDN Europe. Nyquist (Uncle Mo)=s first stakes winner in August, became his second Grade I winner less than a month later with a victory in Sunday=s GI Summer S. at Woodbine. The score in the AWin and You=re In@ event punched Gretzky the Great=s ticket to the GI Breeders= Cup Juvenile Turf and gave Japanese-born jockey Kazushi Kimura his first career Grade I triumph. -

2020 Culberson Cad Certified Mineral Roll (Pdf)

CULBERSON COUNTY APPR DIST JOB NUMBER: 505500 MINERAL APPRAISAL ROLL FOR THE YEAR 2020 (MINERALS, MINERAL RELATED REAL & PERSONAL, AND INDUSTRIAL/UTILITY PROPERTIES) ALPHA SEQUENCE DATE: 7/08/2020 VOLUME 1 OF ___ PRITCHARD & ABBOTT INC SELECT JOB: 505500 CULBERSON COUNTY APPR DIST REPORT YEAR: 2020 SELECT JSC: SELECT OWNER RANGE: 1 TO 9999999 INCLUDE PROTEST VALUE: N SELECT OWNER REND CODE: A SELECT USER OWNER CODE: A SELECT INCLUDE D/OS: Y SELECT LEASE RANGE: 1 TO 9999999 SELECT USER D/O CODE: A SELECT D/O ZERO VALUES: N SELECT LSE HEADER CODE: A SELECT INV. NON-PROD: Y SELECT INV. PERSONNAL: Y SELECT INV. REAL: Y SELECT INV. TEA CODE: SELECT INV. USER CODE: A SELECT INV. COMPLIANCE CODE: SELECT JUR TO PRINT: 00 SELECT MINIMUM OWNER: 0000 INCLUDE PRIVATE ADDRESSES: Y SELECT PRINT VALUES: Y SELECT PRINT LEASE#: Y PRINT TOP 20 RECAP: N SELECT NUMBER COPIES: 1 PRITCHARD & ABBOTT INC * PRITCHARD & ABBOTT INC APPRAISAL ROLL CULBERSON COUNTY APPR DIST JOB - 505500 7/08/2020 PAGE 1 MXLT88WN OWN/ACCT/SEQ NAME AND ADDRESS LEASE# PROPERTY DESCRIPTION OPERATOR/JURISDICTION VALUE 701899 A T LAND COMPANY LLC 11541 AT LANDS STATE UNIT .062500 RI -- APR OPERATING LLC 63,610 11270/00001 2800 POST OAK BLVD STE 5850 G1 PSL CALDWELL CM BLK52 S4 00-01-30-60 HOUSTON TX 77056 A-6442 700848 ACE IN THE HOLE INC 11113 HARRIER 10 .125000 RI -- RING ENERGY 34,550 02777/00001 2671 COUNTY ROAD 41 G1 T2S BLK 58 SEC 10 A-17 00-01-30-60 SUDAN TX 79371-6817 T&P RR/ALLEN J T 701051 ACE IN THE HOLE INC 11298 EVERYTHINGS BIGGER WC .174957 RI -- CONOCOPHILLIPS CO 8,390 04312/00001 -

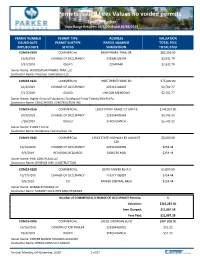

Permits Issued Fees Values No Voided Permits Town of Parker Date Range Between 10/1/2019 and 10/31/2019

Permits Issued Fees Values no voided permits Town of Parker Date Range Between 10/1/2019 and 10/31/2019 PERMIT NUMBER PERMIT TYPE ADDRESS VALUATION ISSUED DATE PERMIT SUBTYPE PARCEL NUMBER TOTAL FEES APPLIED DATE STATUS SUBDIVISION TOTAL PAID COM19-0109 COMMERCIAL 8599 PRAIRIE TRAIL DR $82,256.00 10/4/2019 CHANGE OF OCCUPANCY 223306102004 $2,932.70 5/31/2019 ISSUED COMPARK $2,932.70 Owner Name: WOODSPEAR PRAIRIE TRAIL LLC Contractor Name: Precision Contractors LLC COM19-0141 COMMERCIAL 9985 TWENTY MILE RD $75,000.00 10/2/2019 CHANGE OF OCCUPANCY 223316104007 $2,702.77 7/17/2019 ISSUED LINCOLN MEADOWS $2,702.77 Owner Name: Higher Ground Education / Guidepost Entity Twenty Mile Rd Pa Contractor Name: ENGLEWOOD CONSTRUCTION INC COM19-0156 COMMERCIAL 12919 STROH RANCH CT UNIT B $149,027.00 10/3/2019 CHANGE OF OCCUPANCY 223334405063 $5,743.23 7/26/2019 ISSUED STROH RANCH $5,743.23 Owner Name: E AND T LI LLC Contractor Name: Ponderosa Construction Inc. COM19-0186 COMMERCIAL 12543 STATE HIGHWAY 83 UnitUNIT $5,000.00 326 10/10/2019 CHANGE OF OCCUPANCY 223310204009 $254.44 9/3/2019 REVISIONS REQUIRED GOBLERS NOB $254.44 Owner Name: PINE LANE PLAZA LLC Contractor Name: DIVISION ONE CONSTRUCTION COM19-0189 COMMERCIAL 10970 PARKER RD A-2 $5,000.00 10/17/2019 CHANGE OF OCCUPANCY 223322106007 $254.44 9/6/2019 CO PARKER CENTRAL AREA $254.44 Owner Name: BONBECK PARKER LLC Contractor Name: SUMMIT FACILITIES MAINTENANCE Number of COMMERCIAL/CHANGE OF OCCUPANCY Permits: 5 Valuation: $316,283.00 Fees Charged: $11,887.58 Fees Paid: $11,887.58 COM19-0206 COMMERCIAL -

May01/2021 Kentucky Derby Wager Guide Churchill Downs

1/ST BET // WAGER GUIDE KENTUCKY DERBY MAY01/2021 CHURCHILL DOWNS MEET THE 2021 DERBY CONTENDERS By Johnny D., @XBJohnnyD ESSENTIAL QUALITY: Unbeaten in five career starts, this son of Tapit is the defending Breeders’ Cup Juvenile winner and reigning 2-year-old champ. He’s also the current consensus pick as top 3-year-old. This Brad Cox-trained colt has done everything right in two 2021 starts. He romped home in the Grade 3 Southwest at Oaklawn Park and then out-fought a game, pace scenario- aided Highly Motivated at Keeneland to win the Grade 2 Blue Grass by a neck. He races a bit off the pace early, but can quickly reach contention when prompted. He has won by as much as four and one-quarter lengths and by as little as a neck. Last September, he broke his maiden first time out going six furlongs at Churchill Downs, so you know he likes the track. Jockey Luis Saez seeks redemption aboard this colt for the disappointment and criticism the rider endured following the disqualification of his mount Maximum Security from first to 17th in the 2019 Kentucky Derby. Trainer Brad Cox won last season’s Eclipse Award as the nation’s top trainer. HOT ROD CHARLIE: Ever since stretching out to two turns on the main track and adding blinkers, this son of Preakness winner Oxbow has been a tiger. His first race under those particular circumstances came in the fourth start of his career and resulted in a one-mile maiden score at Santa Anita in October. -

September 26, 2016 Voter 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Alicia Wincze-Hughes CALIF

NTRA Top Thoroughbred Poll NTRA Top Thoroughbred Poll - September 26, 2016 Voter 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Alicia Wincze-Hughes CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE FROSTED BEHOLDER CAVORTING MELATONIN ARROGATE A.P. INDIAN Anthony Stabile CALIFORNIA CHROME FROSTED SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE TEPIN CAVORTING CATCH A GLIMPSE ARROGATE A.P. INDIAN NYQUIST Beverley Smith CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE FROSTED ARROGATE BEHOLDER CATCH A GLIMPSE SHAMAN GHOST A.P. INDIAN Bill Finley CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE FROSTED ARROGATE BEHOLDER CATCH A GLIMPSE MELATONIN NYQUIST Bob Ehalt CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE FROSTED ARROGATE MELATONIN BEHOLDER STELLAR WIND CAVORTING Bob Neumeier CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN ARROGATE SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE MELATONIN CAVORTING A.P. INDIAN DA BIG HOSS FROSTED Brad Telias CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE FROSTED BEHOLDER ARROGATE MELATONIN DORTMUND A.P. INDIAN Brian Zipse CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE FROSTED BEHOLDER ARROGATE STELLAR WIND MELATONIN DA BIG HOSS Carol Holden CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE FROSTED CAVORTING BEHOLDER ARROGATE MELATONIN EXAGGERATOR Dan Illman CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN MELATONIN SONGBIRD FLINTSHIRE BEHOLDER FROSTED STELLAR WIND ARROGATE A.P. INDIAN Danny Brewer CALIFORNIA CHROME SONGBIRD BEHOLDER FROSTED TEPIN FLINTSHIRE LORD NELSON A.P. INDIAN CAVORTING ARROGATE Dick Downey CALIFORNIA CHROME FLINTSHIRE TEPIN SONGBIRD ARROGATE BEHOLDER FROSTED STELLAR WIND DORTMUND EFFINEX Donna Barton Brothers CALIFORNIA CHROME TEPIN SONGBIRD -

Derby Day Weather

Derby Day Weather (The following records are for the entire day...not necessarily race time...unless otherwise noted. Also, the data were taken at the official observation site for the city of Louisville, not at Churchill Downs itself.) Coldest Minimum Temperature: 36 degrees May 4, 1940 and May 4, 1957 Coldest Maximum Temperature: 47 degrees May 4, 1935 and May 4, 1957* (record for the date) Coldest Average Daily Temperature: 42 degrees May 4, 1957 Warmest Maximum Temperature: 94 degrees May 2, 1959 Warmest Average Daily Temperature: 79 degrees May 14, 1886 Warmest Minimum Temperature: 72 degrees May 14, 1886 Wettest: 3.15" of rain May 5, 2018 Sleet has been recorded on Derby Day. On May 6, 1989, sleet fell from 1:01pm to 1:05pm EDT (along with rain). Snow then fell the following morning (just flurries). *The record cold temperatures on Derby Day 1957 were accompanied by north winds of 20 to 25mph! Out of 145 Derby Days, 69 experienced precipitation at some point during the day (48%). Longest stretch of consecutive wet Derby Days (24-hr): 7 (2007-2013) Longest stretch of consecutive wet Derby Days (1pm-7pm): 6 (1989 - 1994) Longest stretch of consecutive dry Derby Days (24-hr): 12 (1875-1886) Longest stretch of consecutive dry Derby Days (1pm-7pm): 12 (1875 - 1886) For individual Derby Day Weather, see next page… Derby Day Weather Date High Low 24-hour Aftn/Eve Weather Winner Track Precipitation Precipitation May 4, 2019 71 58 0.34” 0.34” Showers Country House Sloppy May 5, 2018 70 61 3.15” 2.85” Rain Justify Sloppy May 6, 2017 62 42 -

Running Style

RUNNING STYLE At Quarter Mile Riva Ridge 1972 1 1 ½ Canonero II 1971 18 20 Wire-To-Wire Kentucky Derby Winners: Horse Year Call Lengths Dust Commander 1970 6 11 Majestic Prince 1969 3 2 Authentic 2020 1 ½ This listing represents 23 Kentucky Derby Forward Pass 1968 4 2 ½ Country House 2019 9 6 ¾ Proud Clarion 1967 9 10 winners that have led at each point of call during the Justify 2018 2 ½ race. Points of call for the Kentucky Derby are a Kauai King 1966 1 3 Always Dreaming 2017 2 1 Lucky Debonair 1965 2 head quarter-mile, half-mile, three-quarter-mile, mile, Nyquist 2016 2 ½ stretch and finish. Northern Dancer 1964 6 4 ¼ American Pharoah 2015 3 1 Chateaugay 1963 6 10 From 1875 to 1959 a start call was given for California Chrome 2014 3 2 the race, but was discontinued in 1960. The quarter- Decidedly 1962 9 9 ¼ Orb 2013 16 10 Carry Back 1961 11 18 mile then replaced the start as the first point of call. I’ll Have Another 2012 6 4 ¼ Venetian Way 1960 4 3 ½ Animal Kingdom 2011 12 6 Tomy Lee 1959 2 1 ½ Wire-to-Wire Winner Year Super Saver 2010 6 5 ½ Tim Tam 1958 8 11 Authentic 2020 Mine That Bird 2009 19 21 Iron Liege 1957 3 1 ½ War Emblem 2002 Big Brown 2008 4 1 ½ Needles 1956 16 15 Winning Colors-f 1988 Street Sense 2007 18 15 Swaps 1955 1 1 Spend a Buck 1985 Barbaro 2006 5 3 ¼ Determine 1954 3 4 ½ Bold Forbes 1976 Giacomo 2005 18 11 Dark Star 1953 1 1 ½ Riva Ridge 1972 Smarty Jones 2004 4 1 ¾ Hill Gail 1952 2 2 Kauai King 1966 Funny Cide 2003 4 2 Count Turf 1951 11 7 ¼ Jet Pilot 1947 War Emblem 2002 1 ½ Middleground 1950 5 6 Count Fleet 1943 Monarchos 2001 13 13 ½ Ponder 1949 14 16 Bubbling Over 1926 Fusaichi Pegasus 2000 15 12 ½ Citation 1948 2 6 Paul Jones 1920 Charismatic 1999 7 3 ¾ Jet Pilot 1947 1 1 ½ Real Quiet 1998 8 6 ¾ Sir Barton 1919 Assault 1946 5 3 ½ Regret-f 1915 Silver Charm 1997 6 4 ¼ Hoop Jr.