MRI-Based Assessment of Masticatory Muscle Changes in TMD Patients After Whiplash Injury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

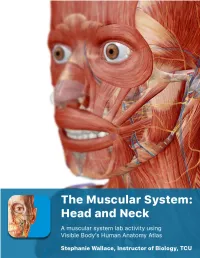

The Muscular System Views

1 PRE-LAB EXERCISES Before coming to lab, get familiar with a few muscle groups we’ll be exploring during lab. Using Visible Body’s Human Anatomy Atlas, go to the Views section. Under Systems, scroll down to the Muscular System views. Select the view Expression and find the following muscles. When you select a muscle, note the book icon in the content box. Selecting this icon allows you to read the muscle’s definition. 1. Occipitofrontalis (epicranius) 2. Orbicularis oculi 3. Orbicularis oris 4. Nasalis 5. Zygomaticus major Return to Muscular System views, select the view Head Rotation and find the following muscles. 1. Sternocleidomastoid 2. Scalene group (anterior, middle, posterior) 2 IN-LAB EXERCISES Use the following modules to guide your exploration of the head and neck region of the muscular system. As you explore the modules, locate the muscles on any charts, models, or specimen available. Please note that these muscles act on the head and neck – those that are located in the neck but act on the back are in a separate section. When reviewing the action of a muscle, it will be helpful to think about where the muscle is located and where the insertion is. Muscle physiology requires that a muscle will “pull” instead of “push” during contraction, and the insertion is the part that will move. Imagine that the muscle is “pulling” on the bone or tissue it is attached to at the insertion. Access 3D views and animated muscle actions in Visible Body’s Human Anatomy Atlas, which will be especially helpful to visualize muscle actions. -

The Role of the Tensor Veli Palatini Muscle in the Development of Cleft Palate-Associated Middle Ear Problems

Clin Oral Invest DOI 10.1007/s00784-016-1828-x REVIEW The role of the tensor veli palatini muscle in the development of cleft palate-associated middle ear problems David S. P. Heidsieck1 & Bram J. A. Smarius1 & Karin P. Q. Oomen2 & Corstiaan C. Breugem1 Received: 8 July 2015 /Accepted: 17 April 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Conclusion More research is warranted to clarify the role of Objective Otitis media with effusion is common in infants the tensor veli palatini muscle in cleft palate-associated with an unrepaired cleft palate. Although its prevalence is Eustachian tube dysfunction and development of middle ear reduced after cleft surgery, many children continue to suffer problems. from middle ear problems during childhood. While the tensor Clinical relevance Optimized surgical management of cleft veli palatini muscle is thought to be involved in middle ear palate could potentially reduce associated middle ear ventilation, evidence about its exact anatomy, function, and problems. role in cleft palate surgery is limited. This study aimed to perform a thorough review of the lit- Keywords Cleft palate . Eustachian tube . Otitis media with erature on (1) the role of the tensor veli palatini muscle in the effusion . Tensor veli palatini muscle Eustachian tube opening and middle ear ventilation, (2) ana- tomical anomalies in cleft palate infants related to middle ear disease, and (3) their implications for surgical techniques used in cleft palate repair. Introduction Materials and methods A literature search on the MEDLINE database was performed using a combination of the keywords Otitis media with effusion is very common in infants with an Btensor veli palatini muscle,^ BEustachian tube,^ Botitis media unrepaired cleft palate under the age of 2 years. -

Questions on Human Anatomy

Standard Medical Text-books. ROBERTS’ PRACTICE OF MEDICINE. The Theory and Practice of Medicine. By Frederick T. Roberts, m.d. Third edi- tion. Octavo. Price, cloth, $6.00; leather, $7.00 Recommended at University of Pennsylvania. Long Island College Hospital, Yale and Harvard Colleges, Bishop’s College, Montreal; Uni- versity of Michigan, and over twenty other medical schools. MEIGS & PEPPER ON CHILDREN. A Practical Treatise on Diseases of Children. By J. Forsyth Meigs, m.d., and William Pepper, m.d. 7th edition. 8vo. Price, cloth, $6.00; leather, $7.00 Recommended at thirty-five of the principal medical colleges in the United States, including Bellevue Hospital, New York, University of Pennsylvania, and Long Island College Hospital. BIDDLE’S MATERIA MEDICA. Materia Medica, for the Use of Students and Physicians. By the late Prof. John B Biddle, m.d., Professor of Materia Medica in Jefferson Medical College, Phila- delphia. The Eighth edition. Octavo. Price, cloth, $4.00 Recommended in colleges in all parts of the UnitedStates. BYFORD ON WOMEN. The Diseases and Accidents Incident to Women. By Wm. H. Byford, m.d., Professor of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children in the Chicago Medical College. Third edition, revised. 164 illus. Price, cloth, $5.00; leather, $6.00 “ Being particularly of use where questions of etiology and general treatment are concerned.”—American Journal of Obstetrics. CAZEAUX’S GREAT WORK ON OBSTETRICS. A practical Text-book on Midwifery. The most complete book now before the profession. Sixth edition, illus. Price, cloth, $6.00 ; leather, $7.00 Recommended at nearly fifty medical schools in the United States. -

Applied Anatomy of the Temporomandibular Joint

Applied anatomy of the temporomandibular joint CHAPTER CONTENTS process which, together with the temporal process of the zygo- Bones . e198 matic bone, forms the zygomatic arch (Fig. 1). The midline fusion of the left and right mandibular bodies Joint .capsule .and .ligaments . e198 provides a connection between the two temporomandibular Intra-articular .meniscus . e198 joints, so that movement in one joint always influences the opposite one. Nociceptive .innervation . e199 Muscles .and .tendons . e199 Joint capsule and ligaments Biomechanical .aspects . e200 Forward movement of the mandible . e200 The joint capsule is wide and loose on the upper aspect around Opening and closing the mouth. e200 the mandibular fossa. Distally, it diminishes in a funnel shaped Grinding movements . e200 manner to become attached to the mandibular neck (Fig. 2). Nerves .and .blood .vessels . e200 Its laxity prevents rupture even after dislocation. Laterally and medially, a local reinforcement of the joint capsule is found. The lateral collateral ligament courses from The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is sited at the base of the the zygomatic arch obliquely downwards and backwards skull and formed by parts of the mandible and the temporal towards the posterior rim of the mandibular neck, lateral to bone, separated by an intra-articular meniscus. It is a synovial the outer aspect of the capsule. At its posterior aspect, it is in joint capable of both hinge (rotation) and sliding (translatory) close relation to the joint capsule and prevents the joint from movements. Like other synovial joints, it may be affected by opening widely. Medially, the joint capsule is locally reinforced internal derangement, inflammatory arthritis, arthrosis, and by the medial collateral ligament. -

EDS Awareness in the TMJ Patient

EDS Awareness in the TMJ Patient TMJ and CCI with the EDS Patient “The 50/50” Myofascial Pain Syndrome EDNF, Baltimore, MD August 14,15, 2015 Generation, Diagnosis and Treatment of Head Pain of Musculoskeletal Origin Head pain generated by: • Temporomandibular joint dysfunction • Cervicocranial Instability • Mandibular deviation • Deflection of the Pharyngeal Constrictor Structures Parameters & Observations . The Myofascial Pain Syndrome (MPS) is a description of pain tracking in 200 Ehlers-Danlos patients. Of the 200 patients, 195 were afflicted with this pain referral syndrome pattern. The MPS is in direct association and correlation to Temporomandibular Joint dysfunction and Cervico- Cranial Instability syndromes. Both syndromes are virtually and always correlated. Evaluation of this syndrome was completed after testing was done to rule out complex or life threatening conditions. The Temporomandibular Joint TMJ Dysfunction Symptoms: Deceptively Simple, with Complex Origins 1) Mouth opening, closing with deviation of mandibular condyles. -Menisci that maybe subluxated causing mandibular elevation. -Jaw locking “open” or “closed”. -Inability to “chew”. 2) “Headaches”/”Muscles spasms” (due to decreased vertical height)generated in the temporalis muscle, cheeks areas, under the angle of the jaw. 3) Osseous distortion Pain can be generated in the cheeks, floor of the orbits and/or sinuses due to osseous distortion associated with “bruxism”. TMJ dysfunction cont. (Any of the following motions may produce pain) Pain With: . Limited opening(closed lock): . Less than 33 mm of rotation in either or both joints . Translation- or lack of . Deviations – motion of the mandible to the affected side or none when both joints are affected . Over joint pain with or without motion around or . -

Innervation of the Temporomandibular Joint Can Be Discussed It Is Necessary First to Describe Its Embryology, Gfoss Anatomy and Microscopic Appe¿Ìrance

à8.ì 'R? INNERVATION OF THE TEMPOROMAI\DIBULAR J AN EXPERIMENTAL AMMAL MODEL USING AUSTRALIAN MERINO STIEEP ABDOLGHAFAR TAHMASEBI-SARVESTANI' B. Sc, M. Sc Thesis submitted for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In The Department of Anatomical Sciences The University of Adelaide (Faculty of Medicine)' Adelaide, South Australia, 5005 April, L997 tfüs tñesisis [elicatelø nl wtfe Aggñleñ ø¡tlour g4.arzi"e tfr.re e c friûfren Ía fiera ñ, fo zic ñ atú fi l-1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am greatly indebted to my supervisors Dr. Ray Tedman and Professor Alastair Goss who first inrroduced me to this freld of study and providing me with the opportunity to carry out this work. I wish to thank them for their constant interest and guidance throughout the course of this study. I am also indebted to the scholarship committee of the Shiraz Medical Science University and Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Iran for gânting me a 4 year scholarship to study at the Universiry of Adelaide. I thank professor Goss and the Japanese Surgical Research team for their expertise in surgical animal models, and Professor July Polak and Dr Mika Hukkanen, Royal postgraduate Medical School London University for their expertise in immunohistochemistry and for providing some of the antisera used in the neuropeptide studies. I would also like to thank Professor Ian Gibbins, Department of Anatomy and Histology of the Flinders Medical Centre for, without the use of his laboratories, materials, and expertise, the double and triple labelling parts of the immunocytochemical work would not have occurred. I also orwe many thanks to Susan Matthew, a senior laboratory officer for her skilful technical assistance in double and triple immunocytochemistry. -

Diagnosis and Treatment of Temporomandibular Disorders ROBERT L

Diagnosis and Treatment of Temporomandibular Disorders ROBERT L. GAUER, MD, and MICHAEL J. SEMIDEY, DMD, Womack Army Medical Center, Fort Bragg, North Carolina Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are a heterogeneous group of musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions involving the temporomandibular joint complex, and surrounding musculature and osseous components. TMD affects up to 15% of adults, with a peak incidence at 20 to 40 years of age. TMD is classified asintra-articular or extra- articular. Common symptoms include jaw pain or dysfunction, earache, headache, and facial pain. The etiology of TMD is multifactorial and includes biologic, environmental, social, emotional, and cognitive triggers. Diagnosis is most often based on history and physical examination. Diagnostic imaging may be beneficial when malocclusion or intra-articular abnormalities are suspected. Most patients improve with a combination of noninvasive therapies, including patient education, self-care, cognitive behavior therapy, pharmacotherapy, physical therapy, and occlusal devices. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxants are recommended initially, and benzodiazepines or antidepressants may be added for chronic cases. Referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon is indicated for refrac- tory cases. (Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(6):378-386. Copyright © 2015 American Academy of Family Physicians.) More online he temporomandibular joint (TMJ) emotional, and cognitive triggers. Factors at http://www. is formed by the mandibular con- consistently associated with TMD include aafp.org/afp. dyle inserting into the mandibular other pain conditions (e.g., chronic head- CME This clinical content fossa of the temporal bone. Muscles aches), fibromyalgia, autoimmune disor- conforms to AAFP criteria Tof mastication are primarily responsible for ders, sleep apnea, and psychiatric illness.1,3 for continuing medical education (CME). -

Diagnosing and Treating Trigeminal Neuralgia in General Dentistry

general practice feature Chasing Pain Diagnosing and Treating Trigeminal Neuralgia in General Dentistry by Steven Olmos, DDS, DABCP, DABCDSM, DABDSM, DAAPM, FAAOP, FAACP, FICCMO, FADI, FIAO As dentists, we know quite a bit about tooth and gum pain, but when it comes to chronic facial pain and neuropathic pain, our dental school education leaves us unprepared. The objective of this article is to explain the differences between men and women with chronic orofacial pain and the relationship to proper functional breathing, using a case study as demonstration. 34 JANUARY 2016 // dentaltown.com general practice feature the United States, nearly half research published in Chest 2015 demonstrates that of all adults lived with chronic respiratory-effort-related arousal may be the most pain in 2011. Of 353,000 adults likely cause (nasal obstruction or mouth breath- 11 aged 18 years or older who were ing). Rising C02 (hypercapnia) in a patient with a surveyed by Gallup-Health- sleep-breathing disorder (including mouth breath- ways, 47 percent reported having at least one of ing) specifically stimulates the superficial masseter three types of chronic pain: neck or back pain, muscles to contract.12 knee or leg pain, or recurring pain.2 Identifying the structural area of obstruction A study published in The Journal of the Amer- (Four Points of Obstruction; Fig. 1) of the air- ican Dental Association October 2015 stated: way will insure the most effective treatment for a “One in six patients visiting a general dentist had sleep-breathing disorder and effectively reduce the experienced orofacial pain during the last year. -

The Myloglossus in a Human Cadaver Study: Common Or Uncommon Anatomical Structure? B

Folia Morphol. Vol. 76, No. 1, pp. 74–81 DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2016.0044 O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E Copyright © 2017 Via Medica ISSN 0015–5659 www.fm.viamedica.pl The myloglossus in a human cadaver study: common or uncommon anatomical structure? B. Buffoli*, M. Ferrari*, F. Belotti, D. Lancini, M.A. Cocchi, M. Labanca, M. Tschabitscher, R. Rezzani, L.F. Rodella Section of Anatomy and Physiopathology, Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy [Received: 1 June 2016; Accepted: 18 July 2016] Background: Additional extrinsic muscles of the tongue are reported in literature and one of them is the myloglossus muscle (MGM). Since MGM is nowadays considered as anatomical variant, the aim of this study is to clarify some open questions by evaluating and describing the myloglossal anatomy (including both MGM and its ligamentous counterpart) during human cadaver dissections. Materials and methods: Twenty-one regions (including masticator space, sublin- gual space and adjacent areas) were dissected and the presence and appearance of myloglossus were considered, together with its proximal and distal insertions, vascularisation and innervation. Results: The myloglossus was present in 61.9% of cases with muscular, ligamen- tous or mixed appearance and either bony or muscular insertion. Facial artery pro- vided myloglossal vascularisation in the 84.62% and lingual artery in the 15.38%; innervation was granted by the trigeminal system (buccal nerve and mylohyoid nerve), sometimes (46.15%) with hypoglossal component. Conclusions: These data suggest us to not consider myloglossus as a rare ana- tomical variant. -

The Mandibular Nerve - Vc Or VIII by Prof

The Mandibular Nerve - Vc or VIII by Prof. Dr. Imran Qureshi The Mandibular nerve is the third and largest division of the trigeminal nerve. It is a mixed nerve. Its sensory root emerges from the posterior region of the semilunar ganglion and is joined by the motor root of the trigeminal nerve. These two nerve bundles leave the cranial cavity through the foramen ovale and unite immediately to form the trunk of the mixed mandibular nerve that passes into the infratemporal fossa. Here, it runs anterior to the middle meningeal artery and is sandwiched between the superior head of the lateral pterygoid and tensor veli palatini muscles. After a short course during which a meningeal branch to the dura mater, and the nerve to part of the medial pterygoid muscle (and the tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini muscles) are given off, the mandibular trunk divides into a smaller anterior and a larger posterior division. The anterior division receives most of the fibres from the motor root and distributes them to the other muscles of mastication i.e. the lateral pterygoid, medial pterygoid, temporalis and masseter muscles. The nerve to masseter and two deep temporal nerves (anterior and posterior) pass laterally above the medial pterygoid. The nerve to the masseter continues outward through the mandibular notch, while the deep temporal nerves turn upward deep to temporalis for its supply. The sensory fibres that it receives are distributed as the buccal nerve. The 1 | P a g e buccal nerve passes between the medial and lateral pterygoids and passes downward and forward to emerge from under cover of the masseter with the buccal artery. -

Tinnitus and Temporomandibular Joint Disorder Subtypes

TINNITUS AND TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT DISORDER SUBTYPES SUSEE PRIYANKA RAVURI A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN DENTISTRY University of Washington 2017 Committee Edmond L. Truelove Peggy Lee Lloyd A. Mancl Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Oral Medicine 1 © Copyright 2017 Susee Priyanka Ravuri 2 University of Washington ABSTRACT Tinnitus And Temporomandibular Joint Disorder Subtypes Susee Priyanka Ravuri Edmond L. Truelove B.S., D.D.S., M.S.D. Oral Medicine OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of tinnitus within a TMD population and to determine an association between the presence of tinnitus and type of TMD diagnoses. METHODS: A secondary data analysis was performed using data from ‘Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) baseline (Validation project) study and follow up (Impact project) study. Self-reported questionnaires for reporting tinnitus and medical history and gold standard diagnoses after clinical examination were used. Log-binomial regression was used to compute risk ratios for tinnitus by TMD subtype and adjusted for patient characteristics. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute), and a two-sided significance level of 0.05 to determined statistical significance (p<0.05). RESULTS: At baseline, 614 subjects met required criteria for TMD diagnosis. Prevalence of tinnitus within sample was 41% (253 of 614). Approximately 80% of TMD subjects received a MPD diagnosis. Tinnitus frequency in the MPD group was 48% (238/495) while subjects without MPD diagnosis the rate of tinnitus was 13% (15 of 119). Using log-binomial regression analysis, the risk ratio for tinnitus was calculated. -

New Knowledge Resource for Anatomy Enables Comprehensive Searches of the Literature on the Feeding Muscles of Mammals

RESEARCH ARTICLE Muscle Logic: New Knowledge Resource for Anatomy Enables Comprehensive Searches of the Literature on the Feeding Muscles of Mammals Robert E. Druzinsky1*, James P. Balhoff2, Alfred W. Crompton3, James Done4, Rebecca Z. German5, Melissa A. Haendel6, Anthony Herrel7, Susan W. Herring8, Hilmar Lapp9,10, Paula M. Mabee11, Hans-Michael Muller4, Christopher J. Mungall12, Paul W. Sternberg4,13, a11111 Kimberly Van Auken4, Christopher J. Vinyard5, Susan H. Williams14, Christine E. Wall15 1 Department of Oral Biology, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America, 2 RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, United States of America, 3 Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America, 4 Division of Biology and Biological Engineering, M/C 156–29, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, United States of America, 5 Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Northeast Ohio Medical University, Rootstown, Ohio, United States of America, 6 Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon, ’ OPEN ACCESS United States of America, 7 Département d Ecologie et de Gestion de la Biodiversité, Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France, 8 University of Washington, Department of Orthodontics, Seattle, Citation: Druzinsky RE, Balhoff JP, Crompton AW, Washington, United States of America, 9 National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, Durham, North Carolina, Done J, German RZ, Haendel MA, et al. (2016) United States of America, 10 Center for Genomic and Computational Biology, Duke University, Durham, Muscle Logic: New Knowledge Resource for North Carolina, United States of America, 11 Department of Biology, University of South Dakota, Vermillion, South Dakota, United States of America, 12 Genomics Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Anatomy Enables Comprehensive Searches of the Berkeley, California, United States of America, 13 Howard Hughes Medical Institute, M/C 156–29, California Literature on the Feeding Muscles of Mammals.