1996-98 NRP Progress Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Bank Branch Location Detail by Branch State AR

US Bank Branch Location Detail by Branch State AR AA CENTRAL_ARKANSAS STATE CNTY MSA TRACT % Med LOCATION Branch ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE CODE CODE Income Type 05 019 99999 9538.00 108.047 Arkadelphia Main Street F 526 Main St Arkadelphia 71923 05 059 99999 0207.00 106.6889 Bismarck AR F 6677 Highway 7 Bismarck 71929 05 059 99999 0204.00 74.9001 Malvern Ash Street F 327 S Ash St Malvern 72104 05 019 99999 9536.01 102.2259 West Pine F 2701 Pine St Arkadelphia 71923 AA FORT_SMITH_AR STATE CNTY MSA TRACT % Med LOCATION Branch ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE CODE CODE Income Type 05 033 22900 0206.00 110.8144 Alma F 115 Hwy 64 W Alma 72921 05 033 22900 0203.02 116.7655 Pointer Trail F 102 Pointer Trl W Van Buren 72956 05 033 22900 0205.02 61.1586 Van Buren 6th & Webster F 510 Webster St Van Buren 72956 AA HEBER_SPRINGS STATE CNTY MSA TRACT % Med LOCATION Branch ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE CODE CODE Income Type 05 023 99999 4804.00 114.3719 Heber Springs F 821 W Main St Heber Springs 72543 05 023 99999 4805.02 118.3 Quitman F 6149 Heber Springs Rd W Quitman 721319095 AA HOT_SPRINGS_AR STATE CNTY MSA TRACT % Med LOCATION Branch ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE CODE CODE Income Type 05 051 26300 0120.02 112.1492 Highway 7 North F 101 Cooper Cir Hot Springs Village 71909 05 051 26300 0112.00 124.5881 Highway 70 West F 1768 Airport Rd Hot Springs 71913 05 051 26300 0114.00 45.0681 Hot Springs Central Avenue F 1234 Central Ave Hot Springs 71901 05 051 26300 0117.00 108.4234 Hot Springs Mall F 4451 Central Ave Hot Springs 71913 05 051 26300 0116.01 156.8431 Malvern Avenue F -

Minnesota Vs. #4/4 Ohio State 1 2

2021 SCHEDULE MINNESOTA VS. #4/4 OHIO STATE DATE OPPONENT TIME TV RESULT Date/Time: Sept. 2, 2021 / 7 p.m. CT Television: FOX SEPTEMBER Site: Minneapolis Gus Johnson (PXP) 2 #4/4 Ohio State* 7:00 p.m. FOX Stadium: Huntington Bank Joel Klatt (Analyst) 11 Miami (OH) 11:00 a.m. ESPNU Surface: FieldTurf Jenny Taft (Reporter) 18 at Colorado 12:00 p.m. PAC12N Capacity: 50,805 Series Overall: Ohio State Leads 45-7 25 Bowling Green^ 11:00 a.m. TBA Minnesota Ohio State Radio: KFAN 2020: 3-4, 3-4 B1G 2020: 7-1, 5-0 B1G Streak: Ohio State Won 11 OCTOBER Mike Grimm (Play by Play) HC P.J. Fleck HC Ryan Day Series in MN: Ohio State Leads 22-4 2 at Purdue* 11:00 a.m. TBA Darrell Thompson (Analyst) 9th Year (5th at Minnesota) 4th Year (all at Ohio State) Streak: Ohio State Won 13 16 Nebraska* TBA TBA Last Meeting: Ohio State won 30-14 Justin Gaard (Reporter) at Minnesota: 26-19 at Ohio State: 23-2 23 Maryland* TBA TBA in Columbus (10/13/18) Corbu Stathes (Host) vs. Ohio State: 0-1 vs. Minnesota: 0-0 30 at Northwestern* TBA TBA Last U win: 29-17 in Columbus Dan Rowbotham (Engineer) Overall Record: 56-41 at Ohio State: 23-2 NOVEMBER (10/14/00) vs. Ohio State: 0-2 vs. Minnesota: 0-0 6 Illinois* TBA TBA Last U win in MN: 35-31 (11/7/81) 13 at Iowa* TBA TBA 20 at Indiana* TBA TBA FIVE THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 27 Wisconsin* TBA TBA * Big Ten game // ^ Homecoming game // All times Central University of Minnesota football begins its 138th season, 1 and fifth under head coach P.J. -

SONG of MINNESOTA Growing up in Fairmont and Southern Minnesota in the 30S, 40S, and 50S

SONG OF MINNESOTA Growing Up In Fairmont and Southern Minnesota in the 30s, 40s, and 50s By George Champine Copyright 2009 George Champine Reproduction forbidden without written approval of the author Contents 1. The America Before 1934 ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.1. America Up to 1920 ..................................................................................................................... 10 1.2. 1920s ............................................................................................................................................ 14 1.3. The 1930s ..................................................................................................................................... 15 1.4. Travel ............................................................................................................................................ 19 1.5. 1930s And Crime .......................................................................................................................... 20 1.6. 1930s And Weather ...................................................................................................................... 21 1.7. Other Aspects of the 1930s Environment ..................................................................................... 22 2. Fairmont as a Midwestern Village ........................................................................................................ 23 2.1. The Champine Family -

U of M Minneapolis Area Neighborhood Impact Report

Moving Forward Together: U of M Minneapolis Area Neighborhood Impact Report Appendices 1 2 Table of Contents Appendix 1: CEDAR RIVERSIDE: Neighborhood Profi le .....................5 Appendix 15: Maps: U of M Faculty and Staff Living in University Appendix 2: MARCY-HOLMES: Neighborhood Profi le .........................7 Neighborhoods .......................................................................27 Appendix 3: PROSPECT PARK: Neighborhood Profi le ..........................9 Appendix 16: Maps: U of M Twin Cities Campus Laborshed ....................28 Appendix 4: SOUTHEAST COMO: Neighborhood Profi le ...................11 Appendix 17: Maps: Residential Parcel Designation ...................................29 Appendix 5: UNIVERSITY DISTRICT: Neighborhood Profi le ......... 13 Appendix 18: Federal Facilities Impact Model ........................................... 30 Appendix 6: Map: U of M neighborhood business district ....................... 15 Appendix 19: Crime Data .............................................................................. 31 Appendix 7: Commercial District Profi le: Stadium Village .....................16 Appendix 20: Examples and Best Practices ..................................................32 Appendix 8: Commercial District Profi le: Dinkytown .............................18 Appendix 21: Examples of Prior Planning and Development Appendix 9: Commercial District Profi le: Cedar Riverside .................... 20 Collaboratives in the District ................................................38 Appendix 10: Residential -

Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Master Plan Minneapolis, Minnesota Adopted by Minneapolis City Council on August 15, 2014

Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Master Plan Minneapolis, Minnesota Adopted by Minneapolis City Council on August 15, 2014 Prepared for: The Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Prepared by: Cuningham Group Architecture, Inc. Donjek, Inc. Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. Blank Page 2 Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Master Plan Steering Committee Robert Stableski, Chair Paul Buchanan Shannon Evans Phill Kelly Crisi Lee Lynn Nyman Daniel Oberpriller Larry Prinds Nicolas Ramirez Table of Contents Kathy Ricketts Hung Russell Executive Summary Sonny Schneiderhan Pierre Willette Section I Neighborhood & Plan Context Special thanks to: Arvonne Fraser Section II Plan Frameworks Section III Character Areas & Recommendations Consultant Team Section IV Cuningham Group Implementation Architecture, Inc. Donjek, Inc. Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. 3 Blank Page 4 Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Master Plan Executive Summary With a vibrant residential and business identity, rich natural amenities along the Mississippi River, and a prime location between the University of Minnesota and downtown Minneapolis, Marcy-Holmes is a sought-after destination, well-traveled gateway, and treasured place to live. Th e neighborhood’s residents describe it as eclectic, diverse, and active, with a rich historical tapestry. It is the oldest neighborhood in the city, proud of its heritage, and yet progressive in its nature; the neighborhood is capable of dealing with change and managing it to benefi t the entire community. It is home to an impressive array of talent: teachers, scientists, senators, artists, students, families, empty-nesters, and many more. Th ese diverse assets are why Marcy-Holmes has experienced dramatic growth for many years. Th e neighborhood has been planning proactively for over ten years, and created their fi rst neighborhood plan in 2003. -

Park & Portland: Vision for Development

PARK & PORTLAND: VISION FOR DEVELOPMENT 2025 PLAN EAST TOWN DEVELOPMENT GROUP East Town is a thriving district of 120 square blocks (300 acres) in the most accessible and visible sector of Downtown Minneapolis. It is bounded by the Minneapolis Central Business District on the west, the Mississippi riverfront to the north, Interstate-35W to the east, and Interstate-94 to the south. The East Town Development work group was formed by the Minneapolis Downtown Council - Downtown Improvement District and the East Town Business Partnership and includes more than 60 organizations and 100 leaders representing businesses, non- profits, elected officials, universities, and neighborhoods. This inter-disciplinary group advances the development goals of Intersections: The Downtown 2025 Plan and hosts monthly strategic presentations ranging from planning and design to projects and critical path with a special focus on diverse housing growth. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRO, GOALS, AND STAKEHOLDERS 2 STUDY AREA & CONTEXT MAP 3 LAND USE MAP 4 ZONING MAP 5 BUILDING HEIGHT MAP 6 OPPORTUNITY SITES MAP 7 OPPORTUNITY SITES 8 STREET SECTIONS 9 RECOMMENDATIONS 10 RESOURCES INTRODUCTION STAKEHOLDERS East Town is thriving! East Town is within a period of great growth and transition. Continued efforts CONTRIBUTERS TO SOURCE MATERIAL of strong planning and neighborhood engagement will help guide the growth to continue building the City of Minneapolis area into a strong cohesive neighborhood. Over the past decade plus many citizens, elected officials, Community Planning & Economic Development (CPED) business community members, developers, designers, and students have collaborated to complete Downtown Minneapolis Neighborhood Association (DMNA) multiple urban studies within the recently created East Town, primarily focusing on the Elliot Park Downtown East Elliot Park (DEEP) Neighborhood and Downtown East Neighborhood. -

Fuji-Ya, Second to None Reiko Weston’S Role in Reconnecting Minneapolis and the Mississippi River

Fuji-Ya, Second to None Reiko Weston’s Role in Reconnecting Minneapolis and the Mississippi River Kimmy Tanaka and Jonathan Moore end of the bridge is a large boulder Nearly three centuries later, with a plaque affixed to it. The plaque another explorer would arrive at ore than two million people recounts the discovery of St. Anthony the opposite end of the bridge and annually cross the Stone Falls by a Franciscan priest, Father behold the place with new eyes. Her M Arch Bridge over the Mis- Louis Hennepin, who first viewed the name was Reiko Umetani Weston. sissippi River at St. Anthony Falls, falls in 1680 and named them for his While Weston introduced many drawn to the history and vibrancy of patron saint, St. Anthony of Padua.1 Minnesotans to Japanese cuisine and the sublime setting. There is the roar There is, of course, more to the culture for the first time through of the falls that can be heard before it story. People knew of the falls prior to her Fuji- Ya restaurant, arguably her can be seen. There are the waves and Father Hennepin’s visit, and it already greatest influence was connecting white foam of the water as it passes had a name— several, in fact. To the a city to its river once again. The over the spillway and crashes on the Dakota, who had guided the priest to restaurant’s physical embodiment— dissipaters below. There is the min- this location, it was called Owamni three solid walls to the city with one eral smell of the mist that is thrust Omni (whirlpool). -

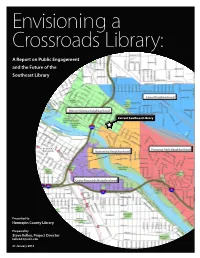

Envisioning a Crossroads Library

Envisioning a Crossroads Library: A Report on Public Engagement and the Future of the Southeast Library Como Neighborhood Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Current Southeast Library Downtown Prospect Park Neighborhood Minneapolis University Neighborhood Cedar Riverside Neighborhood Presented to Hennepin County Library Prepared by Steve Kelley, Project Director [email protected] 21 January 2015 Acknowledgements Project Collaborators Meredith Brandon – Graduate research assistant and report author Steve Kelley – Senior Fellow, project director Bryan Lopez – Graduate research assistant and report author Dr. Jerry Stein – Project advisor Ange Wang – Design methods consultant Sandra Wolfe-Wood – Design methods consultant Community Contributors Najat Ajaram - Teacher at Minneapple International Montessori School Sandy Brick - Local artist and SE Library art curator Sara Dotty - Literary Specialist at Marcy Open School Rev. Douglas Donley - University Baptist Church Pastor Cassie Hartnett – Coordinator of Trinity Lutheran Homework Help Eric Heideman – Librarian at Southeast Library Paul Jaeger – Recreation Supervisor at Van Cleve Recreation Center David Lenander – Head of the Rivendell Group Gail Linnerson – Librarian with Hennepin County Libraries Wendy Lougee - Director of UMN Libraries Jason McLean – Owner and manager of Loring Pasta Bar and Varsity Theater Marji Miller - Executive Director SE Seniors Mike Mulrooney – Owner of Blarney’s Pub in Dinkytown Huy Nguyen - Luxton Recreation Center Director James Ruiz – Support staff member at Southeast Library -

INSTITUTION 74T- The,Original Document. Reproductions V

1. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 123 953 HE 007 470 TITLE All-University Faculty .Tnformation Bulletin, Fall 1974 and Twin-Cities Campus FacultyInformati-on Bulletin Supplement, Fall 1975. INSTITUTION minnesota Univ., Minneapolis.' PVB WiTE 74T- NOTE 118p. EDR$ PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Freedom; *AdmiltiOzative Policy; Administrator 'Responsibility,Ancillary Services; *dellege'Faculty; Faculty Organizations; Fringe Benefits; Gov &nance; *Higher Education; Housing; *Personnel Policy; Research; *State Universities; Teacher Responsibility IDENTIFIERS *Faculty Handbooks; University of Minnesota ^I+ ABSTRACT , The All University Faculty Information Bulletin for 1974 for the university of Minnesota describes the university; its organization and administration; the duties and privileges of the fdculty; faculty personnel,information; teaching policies andl procedures; student services; university resources including research and study facilities, publicatio-is, And support facilities and staff; and the university administration and organization. The suppled fit provides similar information more specifically concerning the Tw n 'Cities Campus. '(JMF) *****vc**************************************************************** * Documenis acquired by ERIC include many inforMai unpublished -* *. materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes eVeryeffort.* * to obtain the best copy available: Nevertheless, items of marginal * 1* reproducibility are often pncoUtte'red and this affec he quality * * of,the microfiche'and hardeopy\reproductions ERICmatravailable * ' * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (BDRSi. EDRS is not- , * responsible for the quality ofthe,original document. Reproductions V * supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. * *********************************************************************** - \ ,,,,:f,,.,o' 4,44!n.,r,, ',,.,.11' '$,,,f ,,-- tr.., t ,i,' *1;4 : . A I 1-pniversity1 FACULTY INFORMATION BULLETIN Fall 1974 - (# 41, '07 !,1!i oil.,. ' 11. .4 I . -

Nightlife in the Twin Cities Music and Entertainment

ACRL National Conference Dave Collins and Aaron Albertson Nightlife in the Twin Cities Music and entertainment he Twin Cities nightlife scene is a great 30 years. Live music by both local bands Tmix of all things that make a city’s night and nationally known artists can be heard life, well…, great. It is a combination of the here pretty much every night. Latin dance famous and the unknown hidden treasure, competitions are held every Thursday eve the upscale proper alongside the dirty and ning. After 10 p.m. on weekend nights, First grungy, and old standards mixing with new Avenue becomes one of the most popular trends. It is easy to find live music any night dance clubs in the Twin Cities. In the past of the week as well as many quiet places to year, Minneapolis Mayor R. T. Rybak has relax by yourself or with friends. done two stage dives at First Avenue at two There are many places to choose from in different shows. every neighborhood of the Twin Cities for an 7th Street Entry— A small club attached evening out. Downtown Minneapolis has a to First Avenue, 7th Street Entry has a more thriving nightlife with bars, restaurants, the intimate setting than First Avenue and is a aters, and concert venues all within walking great place to see local bands. distance of each other. Near the Minneapolis Nye’s Polonaise Room—A Polish Ameri campus of the University of Minnesota is can restaurant serving giant portions, Nye’s the Dinkytown neighborhood. Besides hav also features a piano bar seven nights of the ing a multitude of college student bars, you week and a polka band on weekend nights. -

Local Sales Taxes Minnesota Department of Revenue Fact Sheet

www.revenue.state.mn.us Minneapolis Special Local Taxes 164M Sales Tax Fact Sheet What’s New in 2015 We added the US Bank Stadium taxing information. This is a supplement to Fact Sheet 164, Local Sales and Use Taxes. It describes the special local taxes that are imposed in Minne- apolis. See Fact Sheet 164S for information on special local taxes imposed in other locations in Minnesota. These taxes are adminis- tered by the Minnesota Department of Revenue. Since city ordinances and resolutions do vary, the tax base for special local taxes may differ from the general state and local taxes. Minneapolis Entertainment Tax (applies city wide) The 3 percent entertainment tax applies to: to buy meals, drinks, or other items. Cover and minimum charges are considered admission fees and are subject to • admission fees; entertainment tax. • the use of amusement devices and games; • food, drinks and merchandise sold in public places during Use of amusement devices and games. Entertain- live performances; and ment tax applies to the charge to use amusement devices or • short-term lodging within the city limits. games in Minneapolis. They may be located indoors or outdoors and include items such as jukeboxes, video This tax is in addition to the 6.875 percent state sales tax, games, pool tables, or carnival rides. 0.15 percent Hennepin County sales tax, 0.25 Transit Im- provement sales tax and the 0.5 percent Minneapolis sales tax. The Minneapolis lodging, restaurant, and liquor taxes Examples of items subject to entertainment tax: may also apply. Athletic event admissions (except regular season school games for grades 1—12) Admission fees. -

Alley February 2021

IMPORTANT alleynews.org NEIGHBORHOOD Of, By, and For its NEWS p 4, 5, & 9 Readers Since 1976 VOL. 46, NUMBER 2 ©2021 Alley Communications, Inc. FEBRUARY 2021 @alleynewspaper Tips from a COVID-19 Indian Reservation in New York; Case Investigator REMEMBERING moved to Honolulu in 1945, to East Phillips San Francisco in 1954, to Wash- Neighborhood Laura Waterman Wittstock ington, D.C. in 1971, and to the Feeling Sept. 11, 1937 – January 16, 2021 Twin Cities in 1973 where she Community and contined to: Press Conference Sick and Woman of Wisdom Via • Nurture her family, Words and Voice: The • Speak and write truth to a Major Success Uncertain Cosmos has Grown power, by One More Star • Build trusting relationships By THE EAST PHILLIPS By LINDSEY FENNER between people, cultures, NEIGHBORHOODS INSTITUTE By HARVEY WINJE and organizations, We recently had a COVID • Give unprententious coun- On January 16, the East Phil- scare in our house. I wanted Laura’s compassionate eyes sel to hundreds of people, lips Neighborhood Institute to share a little bit about that closed, her judicious intel- organizations personally (EPNI) hosted a virtual press experience, because even lect chronicled, her indigenous and on many boards of and community conference to though I have had hundreds discuss the future of the Roof wisdom relayed, her correc- directors. Depot building. Community of conversations about how to tions of errant history revealed, For many of us words cope with COVID isolation, I members and elected officials still felt uncertain and unpre- her gracious smile remembered, don’t come as easily as joined together in solidarity pared.