Filtering the Headlines, Such Bias Is a Critical and Necessary Part of the Piece for Two Distinct Reasons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cord • Wednesday

. 1ng the 009 Polaris prize gala page19 Wednesday, September 23. 2009 thecord.ca The tie that binds Wilfrid Laurier University since 1926 Larger classes take hold at Laurier With classes now underway, the ef fects of the 2009-10 funding cuts can be seen in classrooms at Wil frid Laurier University, as several academic departments have been forced to reduce their numbers of part-time staff. As a result, class sizes have in creased and the number of class es offered each semester has decreased.' "My own view is that our admin istration is not seeing the academic side of things clearly;' said professor of sociology Garry Potter. "I don't think they properly have their eyes YUSUF KIDWAI PHOTOGRAPHY MANAGER on the ball as far as academic plan Michaellgnatieff waves to students, at a Liberal youth rally held at Wilt's on Saturday; students were bussed in from across Ontario. ninggoes:' With fewer professors teaching at Laurier, it is not possible to hold . as many different classes during the academic year and it is also more lgnatieff speaks at campus rally difficult to host multiple sections for each class. By combining sections and reduc your generation has no commit the official opposition, pinpointed ing how many courses are offered, UNDA GIVETASH ment to the political process;' said what he considers the failures of the the number of students in each class Ignatieff. current Conservative government, has increased to accommodate ev I am in it for the same The rally took place the day fol including the growing federal defi eryone enrolled at Laurier. -

Anatoliy Gruzd

ANATOLIY GRUZD, PHD Canada Research Chair in Social Media Data Stewardship, Associate Professor, Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University CV Email: [email protected] Twitter: @gruzd Research Lab: http://SocialMediaLab.ca APPOINTMENTS 2014 - present Associate Professor, Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University, Canada Director, Social Media Lab 2010 - 2014 Associate Professor, School of Information Management, Faculty of Management, Dalhousie University, Canada (cross-appointment at the Faculty of Computer Science, Dalhousie University) 2009 (Fall) Adjunct Faculty, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) 2008 - 2009 Adjunct Faculty, Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto 2006 - 2008 Research Assistant, UIUC 2005 (Fall) Teaching Assistant, UIUC 2005 (Spring) Teaching Assistant, School of Management, Syracuse University 2001 - 2003 Computer Science Teacher, Lyceum of Information Technologies, Ukraine EDUCATION PhD in Library & Information Science, Graduate School of Library & Information Science 2005 – 2009 University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA) ▪ Dissertation title: Automated Discovery of Social Networks in Online Learning Communities MS in Library & Information Science, School of Information Studies 2003 – 2005 Syracuse University (Syracuse, NY, USA) BS & MS in Computer Science, Department of Applied Mathematics 1998 – 2003 Dnipropetrovsk National University (Ukraine) Graduated with Distinctions AWARDS, HONORS & GRANTS Grants ▪ eCampus Ontario Research Project ($99,959) 2017-2018 -

Research Report

RESEARCH REPORT OCUFA Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations Union des Associations des Professeurs des Universités de l’Ontario 83 Yonge Street, Suite 300, Toronto, Ontario M5C 1S8 Telephone: 416-979-2117 •Fax: 416-593-5607 • E-mail: [email protected] • Web Page: http://www.ocufa.on.ca Ontario Universities, the Double Cohort, and the Maclean’s Rankings: The Legacy of the Harris/Eves Years, 1995-2003 Michael J. Doucet, Ph.D. March 2004 Vol. 5, No. 1 Ontario Universities, the Double Cohort, and the Maclean’s Rankings: The Legacy of the Harris/Eves Years, 1995-2003 Executive Summary The legacy of the Harris/Eves governments from 1995-2003 was to leave Ontario’s system of public universities tenth and last in Canada on many critical measures of quality, opportunity and accessibility. If comparisons are extended to American public universities, Ontario looks even worse. The impact of this legacy has been reflected in the Maclean’s magazine rankings of Canadian universities, which have shown Ontario universities, with a few notable exceptions, dropping in relation to their peers in the rest of the country. Elected in 1995 on a platform based on provincial income tax cuts of 30 per cent and a reduction in the role of government, the Progressive Conservative government of Premier Mike Harris set out quickly to alter the structure of both government and government services. Most government departments were ordered to produce smaller budgets, and the Ministry of Education and Training was no exception. Universities were among the hardest hit of Ontario’s transfer-payment agencies, with budgets cut by $329.1 million between 1995 and 1998, for a cumulative impact of $2.3 billion by 2003. -

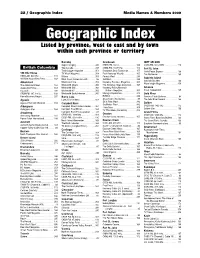

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

In Bed with the CFS | the Eyeopener

HOME ABOUT JOIN US ARCHIVES DOWNLOADS SITEMAP Enter search... NEWS FEATURES BUSINESS SPORTS ARTS & LIFE FUN COMMUNITIES EDITORIAL MULTIMEDIA » Like 258 IN BED WITH THE CFS 34 Comments 15 FEBRUARY 2011 Marta Iwanek As Ryerson Students’ Union president Toby Whitfield prepares to head to his new job for the Canadian Federation of Students, his successor is another darling of the advocacy giant. For the past five years, RSU executive seats have been filled by CFS-friendly candidates. Vidya Kauri and Features editor Mariana Ionova investigate the intimate relationship between the RSU and CFS Subscribe to The Eyeopener Podcast When Toby Whitfield’s term as Ryerson Students’ Union president is up in May, he will on iTunes. head to Ottawa to work for the lobby group that has been influencing Ryerson student politics for the last ten years. As the new treasurer for the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS), Whitfield will be managing the bank account of the most powerful student advocates in Canada. When it comes to student politics, the CFS calls the shots on more than 80 campuses across Canada. It has the power to help elect candidates into executive positions in student unions. 10 Dundas East is giving away 10 $100 Whether the average student knows it or not, the CFS has played a role behind the scenes at Cineplex gift cards, just to #Ryerson students! Ryerson for over a decade. Grab yours at any participating eateries at 10 Dundas. The CFS is the largest student advocacy organization in Canada and was established in 1981 about 19 hours ago to lobby the government for policies that protect students and address their concerns. -

Convocation Ceremonies June 2018 Where Tradition Meets Transformation Convocation Ceremonies June 2018

Where tradition meets transformation Convocation Ceremonies June 2018 Where tradition meets transformation Convocation Ceremonies June 2018 “We are filled with pride in our A Visual university’s legacy of changing History 1950s 1970s 1990s lives, solving challenges, engaging the community and making 2018 marks a very special double anniversary for Ryerson University. Seventy years ago, in 1948, the Ryerson Institute of Technology an impact on the world around us.” was founded under the visionary leadership 1960s 1980s 2000s of Howard H. Kerr. Twenty-five years ago, in 1993, under the exemplary leadership of 1950 1972 1991 First Blue and Gold dance First degrees are awarded Pitman Hall, the first major President Terry Grier, Ryerson was granted to nine Ryerson students co-ed residence, opens — Mohamed Lachemi ------------------------ full university status by the Ontario ------------------------ ------------------------ government, opening the door for graduate President and Vice-Chancellor programs and funded research. 1960 1985 2001 Ryerson University First annual Ryerson Eric McCormack, future Name officially changes For a complete timeline visit picnic in September on the star of Will and Grace, from Ryerson Polytechnic Toronto Islands ryerson.ca/double-anniversary graduates from Ryerson University to Ryerson ------------------------ Theatre School University 1954 ------------------------ ------------------------ Principal Kerr introduces 1978 1992 Share your convocation moments a dress code Lake Devo opens and Canadian astronaut Roberta -

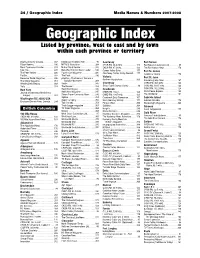

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2007-2008 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

24 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2007-2008 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Boating Industry Canada . 267 Knowledge Network (KN) . 90 Courtenay Fort Nelson Décor Homme. 290 MITACS Newsletter. 388 CFCP-FM, 98.9 mHz . 119 Fort Nelson Cablevision Ltd.. 95 Menz Tournament Hunter . 323 Mutual Fund Review . 326 CKLR-FM, 97.3mHz . 123 The Fort Nelson News . 178 New You . 328 New Westminister News Leader . 180 Comox Valley Echo . 177 Fort St. James The Peer Review . 336 Pacific Golf Magazine . 335 Courtenay Comox Valley Record . 177 Caledonia Courier . 176 Pet Biz. 337 The Peak . 246 Victoria Fort St. John Resource World Magazine. 346 priorities - The Feminist Voice in a Northern Aquaculture . 329 The Shore Magazine . 351 Socialist Movement . 389 Alaska Highway News. 167 WeddingBells Beauty . 369 Realm . 345 Courtenay CHRX-FM, 98.5 mHz . 120 Yalla . 374 The Record . 182 Shaw Cable (Comox Valley) . 96 CKNL-AM, 101.5 mHz. 123 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 124 New York Reel West Digest. 345 Cranbrook Reel West Magazine . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 120 North Peace Express . 180 Journal of Cutaneous Medicine & The Northerner . 181 Surgery. 381 Simon Fraser University News . 246 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 123 Sphère . 353 Washington DC 20005 USA Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 167 Gabriola Island Super Camping . 356 East Kootenay Weekly . 177 Gabriola Sounder . 178 Employee Benefit News Canada. 294 Tow Canada. 359 Forests West. 300 WaveLength Magazine . 368 Truck Logger magazine . 361 GolfWest . 304 Gibsons British Columbia TV Week Magazine . 364 Insights . 246 Coast Independent . -

Sylo Integrates Tezos to the Sylo Smart Wallet

Newswire Analytics Report Sylo Integrates Tezos to the Sylo Smart Wallet Released Friday, December 4, 2020 06:00 AM EST | Newswire Analytics from December 4, 2020 View release on BlockchainWire.io Distribution The Distribution reports provide a listing of the distribution circuits you selected for your release. This includes high-level details on a subset of the recipients of your release. Recipients are listed by circuit, trades, and your own email/fax lists as appropriate. The Top Placements area provides a list of many of the online sites that posted your release, including links to your release on those sites. Full Text Total Potential Reach: 21,841,535 Displaying : 100 Full Text Clips OUTLET POTENTIAL REACH AOL Search 7,840,739 medium.com 6,456,554 markets.ask.com 2,216,768 apnews.com 1,429,405 Townhall Finance 509,438 Star Tribune 443,004 Arizona Republic 350,171 WRAL 321,876 Benzinga 279,311 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel 220,759 asiaone.com 198,486 InvestorPlace 187,205 markets.post-gazette.com 163,051 GlobeNewswire 154,887 Vancouver Sun 114,202 markets.buffalonews.com 107,306 marketscreener.com 98,904 Ottawa Citizen 98,206 Montreal Gazette 95,673 Calgary Herald 83,252 Boston Herald 81,325 Daily Herald 72,963 Edmonton Journal 63,685 Windsor Star 38,688 London Free Press 34,491 Street Insider 34,323 teletrader.com 23,012 Digital Journal 15,901 The Star Phoenix 15,085 Leader-Post 14,372 Rockford Register Star 13,694 My Motherlode 13,533 presstelegram 10,737 Ascensus 7,974 stocks.newsok.com 4,520 markets.chroniclejournal.com 3,397 Spoke -

Carys Mills Twitter.Com/Carysmills Carysmills.Com [email protected]

Carys Mills twitter.com/CarysMills carysmills.com [email protected] Work Experience Reporter, The Toronto Star, Toronto – September 2012 to present Selected to be part of the one-year reporting internship program, which includes rotations through city, national, business and other sections of the newspaper. Reporter, The Globe and Mail, Toronto – July 2011 to September 2012 Reporting features and news for print and online, including breaking news such as the Eaton Centre shooting for Canada’s national newspaper. Political coverage included a two-month placement in Ottawa. Web editor, Report on Business, The Globe and Mail Toronto – June to July 2011 Edited copy and created online assets for the Report on Business including text galleries, photo galleries, audio slideshows, interactive maps and live discussions. I edited audio and photos and used applications including Storify. Radio Room reporter, The Toronto Star, Toronto – October 2010 to May 2011 Monitoring news and emergency scanners to produce breaking news and newspaper content. I contributed to morning live-blogs and found breaking news on social media. Features editor, The Ryersonian, Toronto – October to December 2010 Developing in-depth journalism about Ryerson University as well updating the outlet’s website Reporting intern, The Globe and Mail, Toronto – September to October 2010 Covering news and features in regular and alternative formats for a university credit internship. Reporting intern, The Windsor Star, Windsor – May to September 2010 Filing breaking news, monitoring scanners, covering beats including court and pitching stories. Coverage of the June 2010 Leamington tornado was nominated for an Ontario Newspaper Award. Associate news editor and news editor, The Eyeopener, Toronto – September 2009 to May 2010 Generating ideas, filing FOI requests, assisting reporters and designing pages for the campus paper. -

Together for Change a RETROSPECTIVE of STUDENT INITIATIVES at RYERSON Ronald Stagg

Ronald Stagg Ronald A RETROSPECTIVE OF STUDENT INITIATIVES AT RYERSON A RETROSPECTIVE OF STUDENT AT INITIATIVES Together for Change Ronald Stagg TOGETHER FOR CHANGE A Retrospective of Student Initiatives at Ryerson TOGETHER FOR CHANGE A RETROSPECTIVE OF STUDENT INITIATIVES AT RYERSON Ronald Stagg Author Acknowledgements THE AUTHOR WOULD like to thank the following David Guptil, David Steele and Michael Walton, who individuals who assisted in the research by providing experienced many of the events chronicled here, for information and/or leads as to where information reviewing the manuscript for accuracy, and Tom Sosa could be found: Victoria Bowman, John Corallo, David for clarifying, at the end of the review, one important Crombie, Liz Devine, Robyn Doolittle, Karen Duplisea, fact that no one else was sure of and about which the Michael Durrant, Bruce Elder, Peter Fleming, Darcy Archives does not have a record. Recognition must also Flynn, David Guptil, Arne Kislenko, Mark Lemieux, be given to present and past members of the Ryerson Liane McLarty, Janet Piper, Izabella Pruska-Oldenhof, Centre, who initiated this project and thus leave behind Greg Quinn, Vicki St. Denys, Tom Sosa, David Steele, a record of student involvement perhaps unique in the Ron Taber, and Michael Walton. Thanks also are due written history of universities. to individuals who provided information in passing If any inaccuracies remain in the body of this work, comments, to anyone who has inadvertently been left they are my responsibility. Any broad account such as out of this list, and to those who wish to remain anon- this one is bound to omit other worthy examples. -

Riley Kucheran Curriculum Vitae

Riley Kucheran Curriculum Vitae Contact Information Riley Kucheran Assistant Professor of Design Leadership, School of Fashion; Associate Director, Saagajiwe Centre for Indigenous Communication and Design; Indigenous Advisor, Yeates School of Graduate Studies Cell Phone : 416-702-7804 Office Phone: 416-979-5000 Ex. 543632 Work Email : [email protected] Person Email: r [email protected] Home Address: 5 Graham Cres., Marathon ON PO Box 754, P0T 2E0 Office Address: Rogers Communication Centre, 80 Gould Street, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 2K3 Social Media: @ rskucheran Website: h ttps://www.ryerson.ca/fashion/about/full-time-faculty/Riley-Kucheran/ (In reverse chronological order): Education Ph.D. Communication & Culture, Ryerson & York University, 2017-Ongoing M.A. Communication & Culture, Ryerson & York University, 2015-2017 B.A. Arts & Contemporary Studies, Ryerson University, 2011-2015 Academic Papers & Published Works “On Avoiding a Re-Colonizing Fashion Studies” International Journal of Fashion Studies, Forthcoming. “Luxury and Indigenous Resurgence” in an edited collection by the C anadian Critical Luxury Collective . Intellect Books. Forthcoming. “A Framework for Truth & Reconciliation.” Yeates School of Graduate Studies. February 2020. ryerson.ca/content/dam/graduate/indigenous-graduate-education/FTR_Report_YSGS_2020.pdf “Luxury Place-making in the City.” Cultural Politics 14 (3): 410-412. Duke University Press. November 2018 “Maadaadizi (To Start a Journey): Strategies for Indigenous Luxury Fashion Designers,” Unpublished