Chapter 1 Add to §1.1 Special Judges the Tennessee General Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. V. TAMARIN LINDENBERG, Individually and As Natural

No. JACKSON NATIONAL LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY, PETITIONER v. TAMARIN LINDENBERG, Individually and as Natural Guardian of Her Minor Children ZTL and SML ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI DANIEL W. VAN HORN DANIEL R. ORTIZ AMY M. PEPKE Counsel of Record ELIZABETH E. CHANCE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA GADSON W. PERRY SCHOOL OF LAW BUTLER SNOW LLP SUPREME COURT 6075 Poplar Avenue, LITIGATION CLINIC Suite 500 580 Massie Road Memphis, TN 38119 Charlottesville, VA (901) 680-7200 22903 (434) 924-3127 [email protected] II ROBERT N. HOCHMAN SIDLEY AUSTIN LLP One South Dearborn St. Chicago, IL 60603 (312) 853-7000 I QUESTIONS PRESENTED The Sixth Circuit has struck down Tennessee’s statutory cap on punitive damages. It did so as a matter not of federal law, but as a matter of its own interpretation of the Tennessee Constitution. On June 19, 2019, in McClay v. Airport Mgmt. Services, LLC, No. M2019-00511-SC-R23-CV, the Tennessee Supreme Court accepted certification of the closely related question of whether Tennessee’s non-economic damages cap is consistent with the Tennessee Constitution. That ruling will likely provide clear guidance on the two state constitutional law issues in this case. The questions presented are: 1. Do principles of cooperative federalism, judicial efficiency, and concern for the consistent application of state law compel the Sixth Circuit to certify to the Tennessee Supreme Court three questions of Tennessee law that the Tennesse Supreme Court specifically indicated it was willing to consider, all of which determine liability and the scope of relief in this case, none of which had previously been addressed by the Tennessee Supreme Court, and two of which concern the Tennessee Constitution. -

Some Proposals for Curbing Judicial Abuse of Probation Conditions Andrew Horwitz

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 57 | Issue 1 Article 4 Winter 1-1-2000 Coercion, Pop-Psychology, and Judicial Moralizing: Some Proposals for Curbing Judicial Abuse of Probation Conditions Andrew Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Horwitz, Coercion, Pop-Psychology, and Judicial Moralizing: Some Proposals for Curbing Judicial Abuse of Probation Conditions, 57 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 75 (2000), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol57/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coercion, Pop-Psychology, and Judicial Moralizing: Some Proposals for Curbing Judicial Abuse of Probation Conditions Andrew Horwitz* Table of Contents I. Introduction ........................................ 76 II. The Sad State of Affairs .............................. 79 A. Procedural Obstacles to Appellate Review .............. 81 1. Failure to Appeal ................... .......... 81 2. Reliance on the Contract and Waiver Theories ........ 84 3. Reliance on the Act of Grace Theory .............. 88 B. Limitations on Substantive Appellate Review ........... 90 1. Statutory Challenges ........................... 90 a. Articulating the Standard ..................... 90 b. Applying the Standard ....................... 95 2. Constitutional Challenges ....................... 99 a. The Consuelo-Gonzalez Test ........ ...... 101 b. The Unconstitutional Conditions Test .......... 105 Ill. The Parade of Horribles ............................. 110 A. Infringements onthe Right to Free Speech ............. 110 B. Infringements on the Right to Refrain from Speaking .... -

A National Call to Action

A National Call to Action Access to Justice for Limited English Proficient Litigants: Creating Solutions to Language Barriers in State Courts July 2013 For further information contact: Konstantina Vagenas, Director/Chief Counsel Language and Access to Justice Initiatives National Center for State Courts 2425 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 350 Arlington, VA 22201-3326 [email protected] Additional Resources can be found at: www.ncsc.org Copyright 2013 National Center for State Courts 300 Newport Avenue Williamsburg, VA 23185-4147 ISBN 978-0-89656-287-5 This document has been prepared with support from a State Justice Institute grant. The points of view and opinions offered in this call to action are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policies or position of the State Justice Institute or the National Center for State Courts. Table of Contents Preface and Acknowledgments i Executive Summary ii Introduction iv Chapter 1: Pre-Summit Assessment 1 Chapter 2: The Summit 11 Plenary Sessions 12 Workshops 13 Team Exercises: Identifying Priorities and Developing Action Plans 16 Chapter 3: Action Steps: A Road Map to a Successful Language Access Program 17 Step 1: Identifying the Need for Language Assistance 19 Step 2: Establishing and Maintaining Oversight 22 Step 3: Implementing Monitoring Procedures 25 Step 4: Training and Educating Court Staff and Stakeholders 27 Step 5: Training and Certifying Interpreters 30 Step 6: Enhancing Collaboration and Information Sharing 33 Step 7: Utilizing Remote Interpreting Technology 35 Step 8: Ensuring Compliance with Legal Requirements 38 Step 9: Exploring Strategies to Obtain Funding 40 Appendix A: Summit Agenda 44 Appendix B: List of Summit Attendees/State Delegations 50 Preface and Acknowledgments Our American system of justice cannot function if it is not designed to adequately address the constitutional rights of a very large and ever-growing portion of its population, namely litigants with limited English proficiency (LEP). -

Outline of the U.S. Legal System

OUTLINEOUTLINE OFOF THETHE U.S.U.S. LEGAL LEGAL SYSTEMSYSTEM OUTLINE OF THE U.S.U.S. LEGAL LEGAL SYSTEMSYSTEM Bureau of International Information Programs United States Department of State http://usinfo.state.gov 2004 OUTLINE OF THE U.S.U.S. LEGAL LEGAL SYSTEMSYSTEM CONTENTS INTRODUCTION The U.S. Legal System . 4 CHAPTER 1 History and Organization of the Federal Judicial System . 18 CHAPTER 2 History and Organization of State Judicial Systems . 44 CHAPTER 3 Jurisdiction and Policy-Making Boundaries . 56 CHAPTER 4 Lawyers, Litigants, and Interest Groups in the Judicial Process . 72 CHAPTER 5 The Criminal Court Process . 90 CHAPTER 6 The Civil Court Process . 118 CHAPTER 7 Federal Judges . 140 CHAPTER 8 Implementation and Impact of Judicial Policies . 158 The Constitution of the United States . 177 Amendments to the Constitution of the United States . 192 Glossary . 204 Bibliography . 212 Index . 214 INTRODUCTION THE U.S. LEGAL SYSTEM In this scene from an 1856 painting by Junius Brutus Searns, George Washington (standing, right) addresses the Constitutional Convention, whose members drafted and signed the U.S. Constitution on September 17, 1787. The Constitution is the primary source of law in the United States. 6 OUTLINE OF THE U.S. LEGAL SYSTEM Every business day, courts throughout the predictability and enforceable the United States render decisions that common norms that the rule of law together affect many thousands of provides and the U.S. legal system people. Some affect only the parties to guarantees. a particular legal action, but others ad- This introduction seeks to familiar- judicate rights, benefits, and legal ize readers with the basic structure principles that have an impact on vir- and vocabulary of American law. -

1 in the Chancery Court for Davidson

IN THE CHANCERY COURT FOR DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE TENNESSEEANS FOR SENSIBLE ) ELECTION LAWS, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. 20-0312-III ) HERBERT H. SLATERY III, ) in his official capacity as ) TENNESSEE ATTORNEY GENERAL ) ) and ) ) GLENN FUNK, in his official capacity ) as DISTRICT ATTORNEY GENERAL ) FOR THE 20th JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF ) TENNESSEE, ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS Defendants, Herbert H. Slatery III and Glenn Funk, in their official capacities, submit this memorandum of law in support of their motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to Tenn. R. Civ. P. 12.02(1). INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND The facts recited herein are derived solely from the Plaintiff’s Complaint. They are used only to provide the Court with background and context for this Motion to Dismiss and are not otherwise admitted. 1 Plaintiff is a multicandidate political action committee that advocates against certain election and campaign finance policy by—among other things—filing lawsuits seeking to challenge the constitutionality of state statutes. Defendant Herbert H. Slatery III is Attorney General and Reporter for the State of Tennessee and is tasked with defending the constitutionality of state statutes. See Tenn. Code Ann. § 8-6-109(b)(9). Defendant Glenn Funk is the duly elected District Attorney General for the 20th Judicial District of Tennessee and has the duty of prosecuting violations of state criminal statutes. See Tenn. Code Ann. § 8-7-103. Plaintiff brings this action seeking a declaration that Tenn. Code Ann. § 2-19-142 violates the First and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 19 of the Tennessee Constitution and a permanent injunction enjoining enforcement of that statute. -

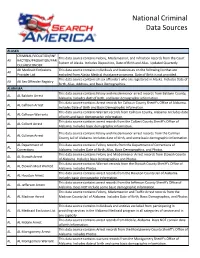

National Criminal Data Sources

National Criminal Data Sources ALASKA CRIMINAL/VIOLATION/INF This data source contains Felony, Misdemeanor, and Infraction records from the Court AK RACTION/PROBATION/PAR System of Alaska. Includes Disposition, Date of Birth and Alias. Updated Quarterly. OLE/ABSCONDER AK Medicaid Exclusions This data source contains Individuals and businesses on the following list that are AK Provider List excluded from Alaska Medical Assistance programs. Date of Birth is not provided. This data source contains all sex offenders who are registered in Alaska. Includes Date of AK AK Sex Offender Registry Birth, Alias, Address, and Basic Demographics. ALABAMA This data source contains felony and misdemeanor arrest records from Baldwin County, AL AL Baldwin Arrest Alabama. Includes date of birth, and basic demographic information. This data source contains Arrest records for Calhoun County Sheriff's Office of Alabama. AL AL Calhoun Arrest Includes Date of Birth and Basic Demographic information. This data source contains Warrant records from Calhoun County, Alabama. Includes date AL AL Calhoun Warrants of birth and basic demographic information. This data source contains arrest records from the Colbert County Sheriff's Office of AL AL Colbert Arrest Alabama. Includes basic demographic information. This data source contains felony and misdemeanor arrest records from the Cullman AL AL Cullman Arrest County Jail of Alabama. Includes date of birth, and some basic demographic information. AL Department of This data source contains Felony records from the Department of Corrections of AL Corrections Alabama. Includes Date of Birth, Alias, Basic Demographics, and Photos. This data source contains Felony and Misdemeanor Arrest records from Etowah County AL AL Etowah Arrest of Alabama. -

In the Chancery Court for the State of Tennessee Twentieth Judicial District, Davidson County, Part Iii

E-FILED 6/4/2020 7:43 PM CLERK & MASTER DAVIDSON CO. CHANCERY CT. IN THE CHANCERY COURT FOR THE STATE OF TENNESSEE TWENTIETH JUDICIAL DISTRICT, DAVIDSON COUNTY, PART III HUNTER DEMSTER, EARLE J. ) FISHER, JULIA HILTONSMITH, ) GINGER BULLARD, JEFF BULLARD, ) ALLISON DONALD, and ) #UPTHEVOTE901, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) vs. ) No. 20-0435-I(III) ) TRE HARGETT, MARK GOINS, ) WILLIAM LEE, and HERBERT ) SLATERY III, each in his official ) capacity of the State of Tennessee, ) ) Respondents ) AND BENJAMIN WILLIAM LAY, CAROLE ) JOY GREENAWALT, and SOPHIA ) LUANGRATH, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) vs. ) No. 20-453-IV(III) ) MARK GOINS, TRE HARGETT, and ) WILLIAM LEE, each in his official ) capacity for the State of Tennessee, ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER GRANTING TEMPORARY INJUNCTION TO ALLOW ANY TENNESSEE REGISTERED VOTER TO APPLY FOR A BALLOT TO VOTE BY MAIL DUE TO COVID-19 1 In this time of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic and its contagion in gatherings of people, almost all states – both Republican and Democrat – are providing their citizens the health protection of a voting by mail option. This includes southern states such as Alabama, South Carolina and Arkansas, and Tennessee‘s neighboring state of Kentucky and nearby West Virginia. The governors, state officials and legislators in those states have spearheaded efforts to expand access to voting by mail to protect the health of their citizens during the pandemic. The Plaintiffs in Case No. 20-453 include some Tennessee registered voters who have or who reside with persons who have autoimmune conditions or other heightened susceptibility to the COVID-19 virus. The Plaintiffs in Case No. 20-435 are all Tennessee registered voters, except for Jeff Bullard. -

From: "Lori Gonzalez"

From: "Lori Gonzalez" <[email protected]> To: [email protected]~ Date: 51251201 2 8:37 AM Subject: TN Courts: Submit Comment on Proposed Rules Submitted on Friday, May 25, 2012 - 8:36am Submitted by anonymous user: [65.13.250.190] Submitted values are: Your Name: Lori Gonzalez Your email address: [email protected] Rule Change: Supreme Court Rule 42 - Standards for Court Interpreters Docket number: M2012-01045-RL2-RL Your public comments: An advisory comment or some other language should be added to emphasize that this amendment specifically allows for interpreter costs to be paid by the AOC in civil court hearings as defined. I personally have spoken with some of the private bar who read the proposed rule as written and did not see the change as made and suggested that the rule was the same as before. Because of the major change in both rules, and more importantly, change in actual procedures that this rule hopes to bring about, additional comments or language emphasizing the civil hearing application would be helpful. The results of this submission may be viewed at: http://www.tncourts.gov/node/602760/submission/2694 pias12 sc- RLZ-RL From: "Heather Hayes" [email protected]~ To: [email protected]~ Date: 51271201 2 2:28 PM Subject: TN Courts: Submit Comment on Proposed Rules Submitted on Sunday, May 27,201 2 - 2:28pm Submitted by anonymous user: [67.212.250.144] Submitted values are: Your Name: Heather Hayes Your email address: [email protected] Rule Change: Supreme Court Rule 42 - Standards for Court Interpreters Docket number: No. -

An Examination of the Tennessee Law of Administrative Procedure George Street Boone

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 1 | Issue 3 Article 1 4-1-1948 An Examination of the Tennessee Law of Administrative Procedure George Street Boone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Recommended Citation George Street Boone, An Examination of the Tennessee Law of Administrative Procedure, 1 Vanderbilt Law Review 339 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol1/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 1 APRIL, 1948 NU111BER 3 AN EXAMINATION OF THE TENNESSEE LAW OF ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE GEORGE STREET BOONE * INTRODUCTION For many years in the United States administrative action has been vigorously criticized and defended, especially in three areas: I in the adjudica- tion of individual cases by administrative agencies; in the consideration of the scope of judicial review of their actions; and in the delegation and exer- cise of their rule-making functions. The American Bar Association's Special Committee on Administrative Law has been active in studying the problems of administrative law and procedure and, in the federal field, has supported legislation in Congress.2 As a result of the efforts of the American Bar As- sociation, of the Attorney General's Committee on Administrative Procedure, and other interested organizations and individuals, Congress, in June, 1946, adopted a Federal Administrative Procedure Act 3 sponsored by the Ameri- 4 can Bar Association. -

In the Supreme Court of Tennessee at Nashville

02/12/2021 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE IN RE: COVID-19 PANDEMIC ___________________ No. ADM2020-00428 ______________________ ORDER MODIFYING AND PARTIALLY LIFTING SUSPENSION OF IN- PERSON COURT PROCEEDINGS On December 22, 2020, the Court extended the State of Emergency and the suspension of jury trials and reinstated the suspension of in-person court proceedings. On January 15, 2021, the Court further extended the suspension of jury trials and of in-person court proceedings. In light of the recent and continuing decline in the number of COVID- 19 cases and hospitalizations in Tennessee, see Executive Order 75, and under the constitutional, statutory, and inherent authority of the Tennessee Supreme Court, the Court adopts the following provisions: 1) The suspension of in-person court proceedings in termination of parental rights cases is lifted effective Monday, March 1, 2021. 2) The suspension of all other in-person court proceedings in all state and local courts in Tennessee, including but not limited to municipal, juvenile, general sessions, trial, and appellate courts, is lifted effective Monday, March 15, 2021. 3) The suspension of all jury trials remains in effect through the close of business on Wednesday, March 31, 2021, subject only to exceptions which may be granted by the Chief Justice on a case-by-case basis. 4) All in-person court proceedings shall be conducted in accordance with the approved comprehensive written plan for the judicial district within which the court is located, which plans shall continue in full force and effect, https://www.tncourts.gov/node/6042449, and in accordance with the following: a) Any permitted in-person court proceedings shall be limited to attorneys, parties, witnesses, security officers, court clerks, and other necessary persons, as determined by the judge and should be scheduled and conducted in a manner to minimize wait time in courthouse hallways. -

2010 Oct.25, 2010Restored.P65

1-TENNESSEE TOWN & CITY/OCTOBER 25, 2010 www.TML1.org 6,250 subscribers www.TML1.org Volume 61, Number 16 October 25, 2010 Survey shows intensified financial pain for municipal governments BY GREGORY MINCHAK balance city budgets. munities. Some are innovating and and Financial pressures are forcing finding creative solutions but, re- CYNDY LIEDTKE HOGAN cities to lay off workers (79 percent), grettably, without the necessary re- Nation’s Cities Weekly delay or cancel capital infrastructure sources, cities will continue to have projects (69 percent), and modify a difficult time assisting their resi- Cities’ finances continue to health benefits (34 percent). There dents through these trying economic weaken under the strain of the reces- were also significant increases in the times.” sion, resulting in cities being less number of officers reporting across- Cities are in the worst fiscal able to meet their fiscal needs in the-board services cuts (25 percent) shape they've been in since the Great 2011 and beyond, according to the and public safety cuts (25 percent). Depression, said the report’s co-au- latest research from NLC. Public safety is usually reduced only thor, Michael A. Pagano, dean of the In NLC’s annual report on cit- as a last resort option. College of Urban Planning and Pub- ies’ fiscal conditions, financial of- NLC President Ronald O. lic Affairs at the University of Illi- Each year, the Downtown Paris SPOOK-tacular, on the historic ficers report the largest spending Loveridge, mayor of Riverside, Ca- nois at Chicago. courthouse lawn, gets bigger and better with delicious concessions, cuts and loss of revenue in the 25- lif., said “the easy cuts are gone” as In most recessions, sales tax col- free craft activities, entertainment and contests by organizations and year history of the survey. -

SCALES Project Appeal Process in a Nutshell

SCALES Project Appeal Process in a nutshell . almost presented on February 12, 2004 by Frank G. Clement, Jr., Judge Court of Appeals of Tennessee If a person, company, organization or governmental entity is a plaintiff or defendant in a lawsuit, (all of whom we generally identify as a “party”) and is dissatisfied with the result of a decision by a court (Juvenile Court, Probate Court, Circuit Court, Chancery Court, Criminal Court), that party may “appeal” the decision to the appropriate appellate court. There are three Tennessee appellate courts (state appellate courts), the Court of Criminal Appeals of Tennessee, the Court of Appeals of Tennessee and the Supreme Court of Tennessee. But for a few exceptions (workers’ compensation appeals being one of them), appeals go directly to either the Court of Criminal Appeals or the Court of Appeals, not to the Supreme Court. The appellate courts do not “try” the case anew (the witnesses do not testify again and there is no jury). The role of the appellate court is to review what occurred in the previous court, with the review limited to and based upon the “official record” from the previous court. The official record from the previous court typically includes the legal papers (civil warrant, complaint, indictment, motions, orders of the previous court, etc.), and usually a transcript of the evidence. The transcript of the evidence is prepared by a stenographer (an independent person who attended the hearing(s) and “recorded” what was said verbatim). If there is no stenographic (verbatim) transcript, the parties and the judge may prepare a summary “statement of the evidence” which is a paraphrased recollection of the testimony (which is not favored due to the differing impressions of what was or was not said).