The Dynamics of Mutual Condemnations in the Filioque Controversy from the Carolingian Era to the Late Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EUCHARIST in EARLY MEDIEVAL EUROPE Celia

THE EUCHARIST IN EARLY MEDIEVAL EUROPE Celia Chazelle In 843 or 844, Pascasius Radbertus, a monk of the Carolingian royal monastery of Corbie and its abbot from 843 to c. 847, presented King Charles the Bald (d. 877) with a special gift: a treatise about the Eucha- rist that Pascasius had written for Corbie’s mission house of Corvey between 831 and 833.1 Located in the eastern Carolingian territory of Saxony, Corvey had been founded from Corbie in 822 to help cement Christianity, and with it Carolingian rule, among the Saxons whom Charlemagne (d. 814) had forcibly converted from paganism around the turn of the ninth century. Pascasius must have recognized the significance of his gift’s timing, made either at Christmas (843) or at Easter (844).2 One of the key precepts expounded in this work, the first Latin treatise specifically on the Eucharist, is that through the Mass, bread and wine are inwardly, mystically changed into the historical flesh and blood of Christ. The sacrament that the king received in the feast honoring the incarnation (Christmas) or resurrection (Easter) was holy food and drink, the source of eternal salvation, because it contained the very body born of Mary in Bethlehem and crucified in Jerusalem. Pascasius wrote De corpore et sanguine Domini (“On the Lord’s Body and Blood”) in the midst of the rebellion of the three older sons of Emperor Louis the Pious (d. 840). By 843, the civil strife this unleashed had torn the Carolingian Empire apart;3 when Louis’ youngest son, 1 I am very grateful to numerous friends and colleagues for generously sharing their knowledge and offering advice on earlier drafts of this article. -

The Nicene Creed in the Church David R

Concordia Journal Volume 41 | Number 1 Article 3 2015 The iceN ne Creed in the Church David Maxwell Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.csl.edu/cj Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Maxwell, David (2015) "The icN ene Creed in the Church," Concordia Journal: Vol. 41: No. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://scholar.csl.edu/cj/vol41/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Concordia Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maxwell: The Nicene Creed The Nicene Creed in the Church David R. Maxwell Pastors often introduce the recitation of the Nicene Creed with the phrase, “Let us confess our Christian faith in the words of the Nicene Creed.” But what do we mean when we identify the content of the faith with the words of the creed? And how does that summary of the faith actually function in the church? After all, if we are to be creedal Christians in any meaningful sense, we would like to see the creed play a more profound role in the church than merely as a text to be recited. But, from the position of one sitting in the pew, it is not always clear what that role would be. Therefore, I will identify and explore three of the ways the creed has functioned and still functions in the church. -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Corpus Christi C: the Eucharist How and Why Fr. Frank Schuster Every

Corpus Christi C: The Eucharist How and Why Fr. Frank Schuster Every so often, on feast days such as Corpus Christi, it is helpful to articulate what the Church means by holding that Jesus Christ our Lord is present in the Eucharist; body, blood, soul, and divinity. That we hold that Jesus is truly present in the Eucharist should come to no surprise because of the number of instances in the New Testament that Jesus says this is so. The last supper as remembered by Mathew, Mark, Luke and First Corinthians quote Jesus when referring to the bread and wine as his body and his blood. Jesus, in John chapter 6, in his bread of life discourse, gives very explicit language regarding how to understand the Eucharist, commanding us to eat his flesh and drink his blood. There are early church writings after the texts in the Bible, such as the Didiche and the Apologies of St. Justin Martyr that speak to the Early Church’s belief in the real presence of Christ. In fact, there are records of tabernacles being established early on for the purpose of reverently housing the Eucharist after Mass for the purpose of bringing the sacrament to the infirm. The belief in the real presence of Christ was simply an accepted tenant of faith for a number of centuries until a controversy erupted in the 9th century. Holy Roman Emperor Charles the Bald had an inquisitive mind and was curious as to whether or not the Eucharist we consume at Mass was also the historical body of the Lord born of the Virgin. -

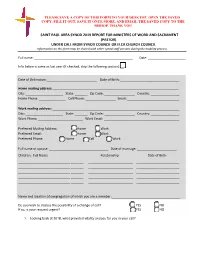

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

John W. Welch, “'All Their Creeds Were an Abomination':A Brief Look at Creeds As Part of the Apostasy,”

John W. Welch, “‘All Their Creeds Were an Abomination’:A Brief Look at Creeds as Part of the Apostasy,” in Prelude to the Restoration: From Apostasy to the Restored Church (Provo, UT and Salt Lake City: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2004), 228–249. “All Their Creeds Were an Abomination”: A Brief Look at Creeds as Part of the Apostasy John W. Welch John W. Welch is a professor of law at Brigham Young University and editor-in-chief of BYU Studies. On October 15, 1843, the Prophet Joseph Smith commented, “I cannot believe in any of the creeds of the different denominations, because they all have some things in them I cannot subscribe to, though all of them have some truth. I want to come up into the presence of God, and learn all things: but the creeds set up stakes, and say, ‘Hitherto [1] shalt thou come, and no further’; which I cannot subscribe to.” While Latter-day Saints gladly and gratefully recognize that all religious creeds contain some truth, the problem is that those formulations of doctrine also contain errors or impose limits that are “incompatible with the gospel’s inclusive commitment to truth and continual [2] revelation.” Such mixing of truth and error is reminiscent of the parable of the wheat and the tares, the Lord’s most [3] salient teaching on the nature of the Apostasy (Matthew 13:24–30, 37–43; JST Matthew 13; D&C 86:1–11). Thus, the creeds themselves, as vessels of mixed qualities, become metaphors or manifestations of the Apostasy itself. -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins. -

Conciliar Traditions of the Catholic Church I: Jerusalem-Lateran V Fall, 2015; 3 Credits

ADTH 3000 01 — Conciliar Traditions of the Catholic Church I: Jerusalem-Lateran V Fall, 2015; 3 credits Instructor: Boyd Taylor Coolman email: [email protected] Office: Stokes Hall 321N Office Hours: Wednesday 10:00AM-12:00 Telephone: 617-552-3971 Schedule: Tu 6:15–9:15PM Room: Stokes Hall 133S Boston College Mission Statement Strengthened by more than a century and a half of dedication to academic excellence, Boston College commits itself to the highest standards of teaching and research in undergraduate, graduate and professional programs and to the pursuit of a just society through its own accomplishments, the work of its faculty and staff, and the achievements of its graduates. It seeks both to advance its place among the nation's finest universities and to bring to the company of its distinguished peers and to contemporary society the richness of the Catholic intellectual ideal of a mutually illuminating relationship between religious faith and free intellectual inquiry. Boston College draws inspiration for its academic societal mission from its distinctive religious tradition. As a Catholic and Jesuit university, it is rooted in a world view that encounters God in all creation and through all human activity, especially in the search for truth in every discipline, in the desire to learn, and in the call to live justly together. In this spirit, the University regards the contribution of different religious traditions and value systems as essential to the fullness of its intellectual life and to the continuous development of its distinctive intellectual heritage. Course Description This course is the first in a two-course sequence, which offers a comprehensive introduction to the conciliar tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. -

The Person of the Holy Spirit

The WORK of the Holy Spirit David J. Engelsma Herman Hanko Published by the British Reformed Fellowship, 2010 www.britishreformedfellowship.org.uk Printed in Muskegon, MI, USA Scripture quotations are taken from the Authorized (King James) Version Quotations from the ecumenical creeds, the Three Forms of Unity (except for the Rejection of Errors sections of the Canons of Dordt) and the Westminster Confession are taken from Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, 3 vols. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1966) Distributed by: Covenant Protestant Reformed Church 7 Lislunnan Road, Kells Ballymena, N. Ireland BT42 3NR Phone: (028) 25 891851 Website: www.cprc.co.uk E-mail: [email protected] South Holland Protestant Reformed Church 1777 East Richton Road Crete, IL 60417 USA Phone: (708) 333-1314 Website: www.southhollandprc.org E-mail: [email protected] Faith Protestant Reformed Church 7194 20th Avenue Jenison, MI 49418 USA Phone: (616) 457-5848 Website: www.faithprc.org Email: [email protected] Contents Foreword v PART I Chapter 1: The Person of the Holy Spirit 1 Chapter 2: The Outpouring of the Holy Spirit 27 Chapter 3: The Holy Spirit and the Covenant of Grace 41 Chapter 4: The Spirit as the Spirit of Truth 69 Chapter 5: The Holy Spirit and Assurance 84 Chapter 6: The Holy Spirit and the Church 131 PART II Chapter 7: The Out-Flowing Spirit of Jesus 147 Chapter 8: The Bride’s Prayer for the Bridegroom’s Coming 161 APPENDIX About the British Reformed Fellowship 174 iii Foreword “My Father worketh hitherto, and I work,” Jesus once declared to the unbelieving Jews at a feast in Jerusalem ( John 5:17). -

The Synod for the Amazon

THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON Marcelo Barros • The divine revelation that arrives late1 • ABSTRACT It is good news that the Synod of Catholic Bishops from around the world, convened by Pope Francis and which will take place in October in Rome, has been prepared with extensive consultation with Amazonian communities and civil organizations working with them. The novelty of this Synod is the call for the Church, instead of acting as a teacher, to listen and hear the voice of the Amazon. In doing so, the Church will discover how to confront the challenges and new possibilities for its mission; a new vision and in opposition to the colonization in which it was complicit. KEYWORDS Spiritual listening | Catholic Church | Earth cry | Amazon peoples | Walk together • SUR 29 - v.16 n.29 • 133 - 138 | 2019 133 THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON There is no doubt that for the peoples of the Amazon, the news that Pope Francis convoked a Synod of Roman-Catholic Bishops from around the world to reflect about the appeals that the Amazon is making to the Universal Church (the body of Christian churches worldwide) was well-received. As Dom Roque Paloschi, president of the Indigenist Missionary Council in Brazil (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - CIMI), affirmed, “the Synod for the Amazon practically began in January of 2018, in Puerto Maldonado (Peru), during the Pope’s meeting with Amazonian people.”2 The Synod of Bishops is an institution that continues an old church custom and enacts the Church’s vocation as a sign and instrument of unity for all of humanity. -

Nicolaus of Cusa and the Council of Florence

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 18, Number 1, January 4, 1991 �TIillPhDosophy Nicolaus of Cusa antl the Council of Florence I. by Helga Zepp-LaRouche Schiller Institute founder Helga Zepp-LaRouche delivered Death, belief in the occult, and schisms in the Church. To this speech to the conference commemorating the 550th anni day, they are the threat tha� entire continents in the devel versary of the Council of Florence, which was held in Rome, oping sector will be wiped out by hunger, the increasingly Italy on May 5,1989. The speech was delivered in German species-threatening AIDS p�demic, Satanism's blatant of and has been translated by John Sigerson. fensive, and an unexampled process of moral decay. The parallels are all too evident, yet this has not halted our head In a period in which humanity seems to be swept into a long rush today into an age even darker than the fourteenth maelstrom of irrationality, it is useful to recall those moments century. The principal problem arises when Man abandons in history in which it succeeded in elevating itself from condi God and the search for a life inspired by this aim. As Nicolaus tions similar to those of today to the maximum clarity of of Cusa said, the finite being is evil to the degree that he Reason. The 550th anniversary of the Council of Florence is forgets that he is finite, believes with satanic pride that he the proper occasion for dealing with the ideas and events is sufficient unto himself, and lapses into a lethargy which which led to such a noble hour in the history of humanity. -

1 Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent Christians Believe That The

Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent1 Christians believe that the Persons of the Trinity are distinct but in every respect equal. We believe also that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father. It is difficult to reconcile claims about the Father’s role as the progenitor of Trinitarian Persons with commitment to the equality of the persons, a problem that is especially acute for Social Trinitarians. I propose a metatheological account of the doctrine of the Trinity that facilitates the reconciliation of these two claims. On the proposed account, “Father” is systematically ambiguous. Within economic contexts, those which characterize God’s relation to the world, “Father” refers to the First Person of the Trinity; within theological contexts, which purport to describe intra-Trinitarian relations, it refers to the Trinity in toto-- thus in holding that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father we affirm that the Trinity is the source and unifying principle of Trinitarian Persons. While this account solves a nagging problem for Social Trinitarians it is theologically minimalist to the extent that it is compatible with both Social Trinitarianism and Latin Trinitarianism, and with heterodox Modalist and Tri-theist doctrines as well. Its only theological cost is incompatibility with the Filioque Clause, the doctrine that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son—and arguably that may be a benefit. 1. Problem: the equality of Persons and asymmetry of processions In addition to the usual logical worries about apparent violations of transitivity of identity, the doctrine of the Trinity poses theological problems because it commits us to holding that there are asymmetrical quasi-causal relations amongst the Persons: the Father “begets” the Son and “spirates” the Holy Spirit.