The Legacy of Paul Nash As an Artist of Trauma, Wilderness and Recovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becky Beasley

BECKY BEASLEY FRANCESCA MININI VIA MASSIMIANO, 25 20134 MILANO T +39 02 26924671 [email protected] WWW.FRANCESCAMININI.IT BECKY BEASLEY b. Portsmouth, United Kingdom 1975 Lives and works in St. Leonards on Sea (UK) Becky Beasley (b.1975, UK) graduated from Goldsmiths College, London in 1999 and from The Royal College of Art in 2002, lives and works in St. Leonards on sea. Forthcoming exhibitions include Art Now at Tate Britain, Spike Island, Bristol and a solo exhibition at Laura Bartlett Gallery, London. Beasley has recently curated the group exhibition Voyage around my room at Norma Mangione Gallery, Turin. Recent exhibitions include, 8TH MAY 1904 at Stanley Picker Gallery, London, P.A.N.O.R.A.M.A at Office Baroque, Antwerp and 13 Pieces17 Feet at Serpentine Pavillion Live Event. Among her most important group exhibitions: Trasparent Things, CCA Goldsmiths, London (2020), La carte d’après nature NMNM, Villa Paloma, Monaco (2010), The Malady of Writing, MACBA Barcelona, (2009), FANTASMATA, Arge Kunst, Bozen (2008), and Word Event, Kunsthalle Basel, Basel (2008). Gallery exhibitions BECKY BEASLEY Late Winter Light Opening 23 January 2018 Until 10 March 2018 Late Winter Light is an exhibition of works which This work, The Bedstead, shows the hotel room The show embraces all the media used by the reveals Beasley’s ongoing exploration of where Ravilious found himself confined by bad artist – photography, sculpture, and, most emotion and ambiguity in relation to everyday weather when he came to Le Havre in the spring recently, video– and touches on many of the life and the human condition. -

A Comparative Analysis of Artist Prints and Print Collecting at the Imperial War Museum and Australian War M

Bold Impressions: A Comparative Analysis of Artist Prints and Print Collecting at the Imperial War Museum and Australian War Memorial Alexandra Fae Walton A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University, June 2017. © Copyright by Alexandra Fae Walton, 2017 DECLARATION PAGE I declare that this thesis has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been submitted, in whole or in part, in any previous application for a degree. Except where stated otherwise by reference or acknowledgement, the work presented is entirely my own. Acknowledgements I was inspired to write about the two print collections while working in the Art Section at the Australian War Memorial. The many striking and varied prints in that collection made me wonder about their place in that museum – it being such a special yet conservative institution in the minds of many Australians. The prints themselves always sustained my interest in the topic, but I was also fortunate to have guidance and assistance from a number of people during my research, and to make new friends. Firstly, I would like to say thank you to my supervisors: Dr Peter Londey who gave such helpful advice on all my chapters, and who saw me through the final year of the PhD; Dr Kylie Message who guided and supported me for the bulk of the project; Dr Caroline Turner who gave excellent feedback on chapters and my final oral presentation; and also Dr Sarah Scott and Roger Butler who gave good advice from a prints perspective. Thank you to Professor Joan Beaumont, Professor Helen Ennis and Professor Diane Davis from the Australian National University (ANU) for making the time to discuss my thesis with me, and for their advice. -

Ravilious: the Watercolours Free

FREE RAVILIOUS: THE WATERCOLOURS PDF James Russell | 184 pages | 28 Apr 2015 | Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd | 9781781300329 | English | London, United Kingdom Eric Ravilious - Wikipedia E ric Ravilious, one of the best British watercolourists of the 20th century, was the very opposite of a tortured artist. It helped perhaps that he always enjoyed acclaim, for his many book illustrations and his ceramic designs, as well as for his paintings. But it was also a matter of temperament. He loved dancing, tennis and pub games, was constantly whistling, and even in the mids found little time for politics, working up only a mild interest in the international crisis or the latest Left Book Club choice. He was, by all Ravilious: The Watercolours, excellent company. Cheerfulness kept creeping in. His delight in the world informs his work. Alan Powers, probably the greatest authority on the artist, has written that "happiness is a quality that is difficult to convey through design, but Ravilious consistently managed to generate it". And David Gentleman has remarked that Ravilious Ravilious: The Watercolours "an easy artist to like". His woodcuts for books and vignettes for Wedgwood the alphabet mug, the boat-race bowlare regularly described as witty and charming. And many of his watercolours, too, attract such epithets as "friendly". Much of his subject-matter Ravilious: The Watercolours pastoral and unassuming, and he was a virtuoso at capturing everyday scenes and little details from English provincial life. Among the sequences of his paintings were those featuring, Ravilious: The Watercolours his words, "lighthouses, rowing-boats, beds, beaches, greenhouses". Even when he became an official war artist, he tended to domesticate any novelty or threat — fighter planes line up harmlessly beyond a garden hedge, and barrage balloons bob cheerfully in the sky. -

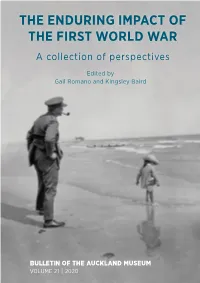

THE ENDURING IMPACT of the FIRST WORLD WAR a Collection of Perspectives

THE ENDURING IMPACT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR A collection of perspectives Edited by Gail Romano and Kingsley Baird ‘That Huge, Haunted Solitude’: 1917–1927 A Spectral Decade Paul Gough Arts University Bournemouth Abstract The scene that followed was the most remarkable that I have ever witnessed. At one moment there was an intense and nerve shattering struggle with death screaming through the air. Then, as if with the wave of a magic wand, all was changed; all over ‘No Man’s Land’ troops came out of the trenches, or rose from the ground where they had been lying.1 In 1917 the British government took the unprecedented decision to ban the depiction of the corpses of British and Allied troops in officially sponsored war art. A decade later, in 1927, Australian painter Will Longstaff exhibited Menin Gate at Midnight which shows a host of phantom soldiers emerging from the soil of the Flanders battlegrounds and marching towards Herbert Baker’s immense memorial arch. Longstaff could have seen the work of British artist and war veteran Stanley Spencer. His vast panorama of post-battle exhumation, The Resurrection of the Soldiers, begun also in 1927, was painted as vast tracts of despoiled land in France and Belgium were being recovered, repaired, and planted with thousands of gravestones and military cemeteries. As salvage parties recovered thousands of corpses, concentrating them into designated burial places, Spencer painted his powerful image of recovery and reconciliation. This article will locate this period of ‘re-membering’ in the context of such artists as Will Dyson, Otto Dix, French film-maker Abel Gance, and more recent depictions of conflict by the photographer Jeff Wall. -

Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists 11 March – 28 June 2020

Press Release 2020 Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists 11 March – 28 June 2020 Pallant House Gallery is delighted to announce an exhibition of artworks depicting Britain’s animals, birds and natural life to mark the 300th anniversary of the birth of ‘Britain’s first ecologist’ Gilbert White of Selborne. Featuring works by artists including Thomas Bewick, Eric Ravilious, Clare Leighton, Gertrude Hermes and John Piper, it highlights the natural life under threat as we face a climate emergency. The parson-naturalist the Rev. Gilbert White Eric Ravilious, The Tortoise in the Kitchen Garden (1720 – 1793) recorded his observations about from ‘The Writings of Gilbert White of Selborne’, ed., the natural life in the Hampshire village of H.J. Massingham (London, The Nonsuch Press, Selborne in a series of letters which formed his 1938), Private Collection famous book The Natural History and Antiquities editions, it is believed to be the fourth most- of Selborne. White has been described as ‘the published book in English, after the Bible, the first ecologist’ as he believed in studying works of Shakespeare and John Bunyan’s The creatures in the wild rather than dead Pilgrim’s Progress. Poets such as WH Auden, specimens: he made the first field observations John Clare, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge have to prove the existence of three kinds of leaf- admired his poetic use of language, whilst warblers: the chiff-chaff, the willow-warbler and Virginia Woolf declared how, ‘By some the wood-warbler – and he also discovered and apparently unconscious device of the author has named the harvest-mouse and the noctule bat. -

Fttfe MUSEUM of MODERN1 ART

jr. ,•&-*- t~ V* *«4* /C^v i* 41336 - 2Z f± **e y^^A-^-^p, fttfE MUSEUM OF MODERN1 ART P WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK -uEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-89CO FOE IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Note* Photographs of paintings available) BRITAIN DELIVERS WAR PAINTINGS TO MUSEUMxOF MODERN ART. LORD HALIFAX TO OPEN EXHIBITION. On Thursday evening, May 22, Lord Halifax, Great Britain's Ambassador to the United States, will formally open at the Museum of Modern Art an exhibition of the Art of Britain At War, designed to show the wartime roles England assigns to her artists and de signers. It will be composed of oils, watercolors, drawings, prints, posters, cartoons, films, photographs, architecture and camouflage of the present war as well as work of British artists during the first World War. The exhibition will open to the public Friday morning, May 23, and will remain on view throughout the summer. It will then be sent by the Museum to other cities in the United States and Canada, The nucleus of the exhibition opening in May will be the group of paintings, watercolors and prints which the Museum expected to open as a much smaller exhibition in November 1940. After several postponments the Museum was finally forced to abandon it as, due to wartime shipping conditions, the pictures did not arrive although word had been received that the shipment had left London early in November. The Museum received the shipment late in January. After weeks of further negotiation with British officials in this country and by cable with London the Museum decided that it would be possible to augment the material already received with other work done by British artists since the first material was sent. -

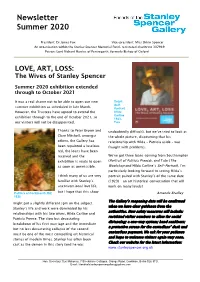

Newsletter Summer 2020

Newsletter Summer 2020 President: Dr James Fox Vice-president: Miss Shirin Spencer An organisation within the Stanley Spencer Memorial Fund, registered charity no 307989 Patron: Lord Richard Harries of Pentregarth, formerly Bishop of Oxford LOVE, ART, LOSS: The Wives of Stanley Spencer Summer 2020 exhibition extended through to October 2021 It was a real shame not to be able to open our new Detail: Self- summer exhibition as scheduled in late March. Portrait, However, the Trustees have agreed to extend the Hilda Carline exhibition through to the end of October 2021, so 1923, our visitors will not be disappointed. Tate Thanks to Peter Brown and undoubtedly difficult), but we’ve tried to look at Clare Mitchell, amongst the whole picture, discovering that his others, the Gallery has relationship with Hilda – Patricia aside – was been repainted a luscious fraught with problems. red, the loans have been received and the We’ve got three loans coming from Southampton exhibition is ready to open (Portrait of Patricia Preece), and Tate (The as soon as permissible. Woolshop and Hilda Carline’s Self-Portrait). I’m particularly looking forward to seeing Hilda’s I think many of us are very portrait paired with Stanley’s of the same date familiar with Stanley’s (1923) – an art historical conversation that will unconventional love life, work on many levels! Patricia at Cockmarsh Hill, but I hope that this show Amanda Bradley 1935 The Gallery’s reopening date will be confirmed might put a slightly different spin on the subject. when we have clear guidance from the Stanley’s life and work were dominated by his authorities. -

{TEXTBOOK} Ravilious and Co the Pattern of Friendship 1St Edition Ebook Free Download

RAVILIOUS AND CO THE PATTERN OF FRIENDSHIP 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andy Friend | 9780500239551 | | | | | Ravilious and Co The Pattern of Friendship 1st edition PDF Book It follows their beautifully produced series of illustrated books on Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden. Gallery profile. It's perhaps stronger on the art than the personal but the treatment of the various infidelities within the Ravilious marriage is frank without becoming scurrilous or accusatory. The exhibition features the work of Ravilious alongside work by his contemporaries, some of which has never been exhibited before. I would like to pass on a huge thank you to everyone who attended the workshop at The Earth Trust on such a hot and humid day. Meritocracy makes a new ruling class Innovation has often come from hard work by unlettered people. Each artist is the subject of a minute programme examining their relationship with some of the major events of the 20th century, including World War One. It hosts one of the most significant public art collections in the South of England and draws over , visitors a year. Saturday 5th October, at 7. The lesser pebbles become sand. He makes you feel that each object matters immensely, that it has become inextricably tangled with his experience, and that he wants desperately to show you what it is really like. About the Author Andy Friend has spent a decade researching the life and work of Eric Ravilious and his extensive circle. Paul Nash: Artist at War. A Sense Of Englishness. For a brief period during the s, some of the most celebrated 20th century British artists including Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden and Enid Marx studied together at the Royal College of Art. -

Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious: Design Free Ebook

FREEEDWARD BAWDEN AND ERIC RAVILIOUS: DESIGN EBOOK Brian Webb,Peyton Skipwith | 64 pages | 30 Oct 2005 | ACC Art Books | 9781851495009 | English | Woodbridge, United Kingdom Read Download Edward Bawden Eric Ravilious Design PDF – PDF Download Design is an excellent introduction to the work of two major British designers and artists, Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious Featuring some previously unpublished images, this book presents, in over illustrations, every aspect of their creativity, including advertising, designs for wallpapers, posters, book jackets, trade cards and ceramics. Bawden and Ravilious met in the Design School of the Royal College of Art inmembers of a generation of students described by Paul Nash, one of their tutors, as belonging to 'an outbreak of talent'. Their shared interests in illustration led to experiments in print making. Bawden's early attempts at lino-cutting developed into a skill that he used until the end of his life. Ravilious quickly developed into one of the most renowned wood engravers Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious: Design the twentieth century. Book illustrator, wallpaper, textile and poster designer, watercolorist, mural painter, teacher. His designs still resonate strongly with young designers more than a quarter-of-a-century after his death. Bawden's influence on 20th-century design is beyond measure. This book brings together forty-five of Edward Bawden's watercolours from World War II, now housed in the Imperial War Museum collection and many published here for the first time, to produce a fascinating -

The Autobiography of Tirzah Garwood Free Ebook

FREELONG LIVE GREAT BARDFIELD: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF TIRZAH GARWOOD EBOOK Tirzah Garwood,Anne Ullmann | 512 pages | 20 Oct 2016 | Persephone Books Ltd | 9781910263099 | English | London, United Kingdom Long Live Great Bardfield, by Tirzah Garwood Jan 4, An autobiography written in a very accessible chatty style, depicting the lives of writers (or in this case artists) living in the first half of the last. Long Live Great Bardfield, & Love to You All The Autobiography of Tirzah Garwood. £ ISBN: Artist(s): Tirzah Garwood, Ravilious Author(s): Anne. Oct 18, But she was also a wonderful writer, and this week, Persephone republishes her singular autobiography Long Live Great Bardfield, a book she. Tirzah Garwood In she had the first of her three children. In – the year she was operated on for breast cancer – she wrote her autobiography (in the evening, after the. Long Live Great Bardfield book. Read 13 reviews from the world's largest community for readers. When Tirzah Garwood was 18, she went to Eastbourne School. Oct 18, But she was also a wonderful writer, and this week, Persephone republishes her singular autobiography Long Live Great Bardfield, a book she. Tirzah Garwood: portrait of the artist and her circle Long Live Great Bardfield book. Read 13 reviews from the world's largest community for readers. When Tirzah Garwood was 18, she went to Eastbourne School. When Tirzah Garwood was 18 she went to Eastbourne School of Art and here she was taught by Eric Ravilious. Over the next four years she did many wood. Long Live Great Bardfield, & Love to You All The Autobiography of Tirzah Garwood. -

Stanley Spencer's 'The Resurrection, Cookham': a Theological

Stanley Spencer’s ‘The Resurrection, Cookham’: A Theological Commentary Jessica Scott “The Resurrection, Cookham”, in its presentation of an eschatology which begins in the here and now, embeds a message which speaks of our world and our present as intimately bound with God for eternity. This conception of an eternal, connecting relationship between Creator and creation begins in Spencer’s vision of the world, which leads him to a view of God, which in turn brings him back to himself. What emerges as of ultimate significance is God’s giving of God’s self. Truth sees God, wisdom beholds God, and from these two comes a third, a holy wondering delight in God, which is love1 It seems that Julian of Norwich’s words speak prophetically of Spencer’s artistic journey - a journey which moves from seeing, to beholding, to joy. Both express love as the essential message of their work. Julian understood her visions as making clear that for God ‘love was his meaning’. Spencer, meanwhile, described his artistic endeavour as invigorated by love, as art’s ‘essential power’. This love, for both, informs the whole of life. God, in light of the power of love, cannot be angry. Julian conceived of sin as something for which God would not blame us. Likewise, Spencer’s Day of Judgement is lacking in judgement. Humanity, in light of the power of love, should not despise itself, not even the bodily self so frequently derided. This love of self finds expression in Julian’s language – she uses ‘sensuality’ when referring to the body.2 Rather than compartmentalising flesh in disregard for it, she 1 Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love, Chapter 44. -

Nash, Nevinson, Spencer, Gertler, Carrington, Bomberg: a Crisis of Brilliance, 1908 – 1920 Dulwich Picture Gallery 12 June – 22 September 2013

Nash, Nevinson, Spencer, Gertler, Carrington, Bomberg: A Crisis of Brilliance, 1908 – 1920 Dulwich Picture Gallery 12 June – 22 September 2013 David Bomberg (1890 – 1957) David Bomberg, Racehorses, 1913, black chalk and wash on paper, 42 x 67 cm, Ben Uri, The London Jewish Museum of Art © The Estate of David Bomberg, All Right Reserved, DACS 2012 David Bomberg, Sappers Under Hill 60, 1919, pencil, ink and wash, 12 x 16 cm, Ben Uri, The London Jewish Museum of Art © The Estate of David Bomberg, All Right Reserved, DACS 2012 David Bomberg, Circus Folk, 1920, oil on paper, 42 x 51.5cm, UK Government Art Collection, © Estate of David Bomberg. All rights reserved, DACS 2012 David Bomberg, In the Hold, 1913-14, oil on canvas, 196.2 x 231.1 cm, © Tate, London 2012 David Bomberg, David Bomberg [self-portrait], c. 1913-14, black chalk, 55.9 x 38.1 cm, © National Portrait Gallery, London. © The Estate of David Bomberg. All rights reserved, DACS 2012 David Bomberg, Bathing Scene, c.1912‑13, oil on wood, 55.9 x 68.6cm, © Tate, London 2012 David Bomberg, Study for 'Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company, Hill 60, St Eloi', 1918-19, oil on canvas, 304.2 x 243.8 cm, ©Tate, London 2012 Dora Carrington (1893 - 1932) Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey, 1916, oil on panel, 50.8 x 60.9 cm, © National Portrait Gallery, London Dora Carrington, Mark Gertler, c. 1909-11, pencil on paper, 41.9 x 31.8 cm, © National Portrait Gallery, London Dora Carrington, Dora Carrington, c. 1910, pencil on paper, 22.8 x 15.2 cm, © National Portrait Gallery, London Dora