Fooling Around with Stories: Children's Books, Oral Lore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Macdonald to Uncle Sam. INSTITUTION National Council on Economic Education, New York, NY

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 842 SO 035 360 AUTHOR McCorkle, Sarapage, Ed.; Suiter, Mary, Ed. TITLE Old MacDonald to Uncle Sam. INSTITUTION National Council on Economic Education, New York, NY. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 64p. CONTRACT R304A010003 AVAILABLE FROM National Council on Economic Education, 1140 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10036. Tel: 800-338-1192 (Toll Free); Fax: 212-730-1793; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.ncee.net/. For full text: http://www.ncee.net/ ei/lessons/OldMac/. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Collaborative Writing; *Curriculum Development; *Economics; *Economics Education; Elementary Secondary Education; Instructional Materials; *Teacher Developed Materials IDENTIFIERS Content Area Teaching; *Economic Concepts; Educational Writing; National Council on Economic Education ABSTRACT This publication contains six lessons for elementary, middle, and high school classrooms developed by writers from Belarus, Croatia, Hungary, Kyrgyzstan, Romania, Russia, and the United States. The authors of these lessons were participants in the Training of Writers program developed and conducted by the National Council on Economic Education, as part of the Cooperative Education Exchange Program. Since 1996 the program has helped teachers learn how to write instructional materials, through intensive writing exercises, expert guidance, feedback -

Ms. Gina's Weekly News

Ms. Gina’s Weekly News Week of March 30 – April 3, 2020 Dear Parents, Welcome to another week of at home learning! I want to thank you all again for your support during this time, I know it isn’t easy for any of us but I think we are doing a pretty good job working together I enjoy seeing all the pictures of the children and what they’re doing at home! This week as we continue with our living things unit, we will be focusing on different kinds of farm animals. Farm animals are mammals and have the same basic needs as humans. We will learn about ways to care for farm animals and the ways farm animals are helpful to us. Take care and be well! Ms. Gina Monday March 30, 2020 At home activity: Ask your child to sing the song “Old MacDonald Had a Farm”. You can look around your home for toy animals and take turns substituting the name of the animals in the song. Ask your child if farm animals are living things, how do we know? (Farm animals need water, food, and air to live. They also grow and change and have babies. All these things make them “Alive”.) Has anyone ever visited a farm before? Remind your child of that experience, what were some animals you saw? Ask your child to draw a picture of their favorite animal that lives on a farm. Remember to have your child write their names on their drawings for practice! Video Suggestion: Old MacDonald Had A Farm (2018) | Nursery Rhymes | Super Simple Songs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_6HzoUcx3eo Book Suggestion: Mrs. -

2017 Songs for Spur of the Moment

Infant (0-14 months) Songs for the Spur of the Moment! ! Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star This Little Piggy Pat-a-cake If You’re Happy and You Know It! Jack and Jill Head and Shoulders Itsy-Bitsy Spider Row, Row, Row, Your Boat Hickory Dickory Dock I’m A Little Teapot You are My Sunshine This is the way we… Mr. Sun Peas Porridge Hot The Wheels on the Bus Five Little Monkeys Baa Baa Black Sheep Humpty Dumpty Hickory Dickory Dock Old MacDonald Had a Farm Roley Poley ! 16 Gestures by 16 Months: www.firstwordsproject.com ! Nippising Screens: www.endds.com (for screen to be sent to your email regularly) ! Speech & Language Milestones (Chinese, Arabic, Farsi, German, Italian, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Russian, Somali, Spanish, Tagalog, Urdu, Vietnamese) www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/earlychildhood/speechlanguage/index.aspx May 2017 Go to www.e3.ca (click on Early Literacy at the top) For Preschool, Toddler, and Infant Early Literacy Booklets, activity calendars, videos, & more! Stages of Play, Language, and Literacy Development Pretend Play Development Language Development Literacy Development Birth- -looks at & follows objects with eyes -by 3 months, baby begins to “take turns” cooing and -likes looking at black & white patterns 3 mths -out of sight, out of mind gurgling -likes rhythm in voice when reading/singing 3-9 -baby mouths and shakes things -purposeful eye contact- watches your face when you speak -explores books by putting them in their months -loves Peek-a-Boo, Pat-a-Cake, etc… -has different cries for different needs -

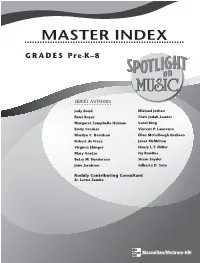

Electronic Master Index

MASTER INDEX GRADES Pre-K–8 SERIES AUTHORS Judy Bond Michael Jothen René Boyer Chris Judah-Lauder Margaret Campbelle-Holman Carol King Emily Crocker Vincent P. Lawrence Marilyn C. Davidson Ellen McCullough-Brabson Robert de Frece Janet McMillion Virginia Ebinger Nancy L.T. Miller Mary Goetze Ivy Rawlins Betsy M. Henderson Susan Snyder John Jacobson Gilberto D. Soto Kodály Contributing Consultant Sr. Lorna Zemke INTRODUCTION The Master Index of Spotlight on Music provides convenient access to music, art, literature, themes, and activities from Grades Pre-K–8. Using the Index, you will be able to locate materials to suit all of your students’ needs, interests, and teaching requirements. The Master Index allows you to select songs, listening selections, art, literature, and activities: • by subject • by theme • by concept or skill • by specific pitch and rhythm patterns • for curriculum integration • for programs and assemblies • for multicultural instruction The Index will assist you in locating materials from across the grade levels to reinforce and enrich learning. A Published by Macmillan/McGraw-Hill, of McGraw-Hill Education, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., Two Penn Plaza, New York, New York 10121 Copyright © by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. The contents, or parts thereof, may be reproduced in print form for non-profit educational use with SPOTLIGHT ON MUSIC, provided such reproductions bear copyright notice, but may not be reproduced in any form for any other purpose without the prior written consent of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., including, but not limited to, network storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

Songs for Babies

Infant (0-14 months) Songs for the Spur of the Moment! ! Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star This Little Piggy Pat-a-cake If You’re Happy and You Know It! Jack and Jill Head and Shoulders Itsy-Bitsy Spider Row, Row, Row, Your Boat Hickory Dickory Dock I’m A Little Teapot You are My Sunshine This is the way we… Mr. Sun Peas Porridge Hot The Wheels on the Bus Five Little Monkeys Baa Baa Black Sheep Humpty Dumpty Hickory Dickory Dock Old MacDonald Had a Farm Roley Poley 16 Gestures by 16 Months: www.firstwordsproject.com Nippising Screens: www.endds.com (for screen to be sent to your email regularly) Speech & Language Milestones (Chinese, Arabic, Farsi, German, Italian, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Russian, Somali, Spanish, Tagalog, Urdu, Vietnamese) www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/earlychildhood/speechlanguage/index.aspx Go to www.simcoecommunityservices.ca (click on EarlyON Child and Family Centre then click on Literacy link) For Preschool, Toddler, and Infant Early Literacy Booklets, activity calendars, videos, & more! May 2017 Stages of Play, Language, and Literacy Development Pretend Play Development Language Development Literacy Development Birth- -looks at & follows objects with eyes -by 3 months, baby begins to “take turns” cooing and -likes looking at black & white patterns 3 mths -out of sight, out of mind gurgling -likes rhythm in voice when reading/singing 3-9 -baby mouths and shakes things -purposeful eye contact- watches your face when you speak -explores books by putting them in their months -loves Peek-a-Boo, Pat-a-Cake, -

(Iial) Second Additional Language (Sal) Grade 2 Lesson Plans

INCREMENTAL INTRODUCTION OF AFRICAN LANGUAGES (IIAL) SECOND ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE (SAL) GRADE 2 LESSON PLANS 1 FOREWORD BY THE DIRECTOR- GENERAL: BASIC EDUCATION The South African Constitution and the Language in Education Policy promotes multilingualism. Multilingualism is an important tool for social cohesion, and for individual and social development. South Africa is a multilingual country with eleven official languages. It is important, therefore, that children learn additional languages as early as possible. There are many cognitive advantages of learning languages hence the provision of these lesson plans to guide you in teaching a second additional language. In its bid to ensure that all official languages are accorded parity of esteem and that multilingualism is promoted in all schools, the Department of Basic Education has planned to implement the Incremental Introduction of African Languages (IIAL) in 2016 in Grade 1 and thereafter incrementally to the next Grades. To support the implementation of IIAL, lesson plans have been developed by the Department of Basic Education (DBE) to enable teachers to teach all the official languages at the Second Additional Language (SAL) level in the Foundation Phase as IIAL is introduced at the specific Grade. The lesson plans are a component of the SAL Toolkits for each grade. In Grade 2 the toolkit comprises a workbook of 40 worksheets, 12 conversational posters linked with the 12 themes of the workbook, an anthology of stories, Big Books and Audio Resources. The lesson plans are: aligned -

Page 1 Don Gray Arrangements October, 2017 Music Category Title

Page 1 Don Gray Arrangements October, 2017 Tempo S= slow, freely Music M=medium, swing Category Title F=fast Description Show Adelaid's Lament S (SA) from Guys and Dolls Show An Old-fashioned Walk S old movie song Show Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better F for two choruses, or quartets male /female Show Aloha Oe S Hawiian folk song Show Along The Navaho Trail M Western Show America The Beautiful M patriotic Show Amazing Grace (six part) S Gospel Show Amazing Grace (for quartet) S Gospel Show Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better F Annie Get Your Gun; for 2 choruses Show Anchors Aweigh F patriotic Show Anywhere I Wander S bass solo Show Aquarius/Let The Sun Shiine In F 60's pop Show Armed Forces Medley F patrotic Show Asleep In The Deep S bass feature Show Atlantis M 60's pop Show Ave Maria (Schubert) S religious Show Auld Lang Syne S Christmas/New Year's Show Back From The Dead F modern Pop tune Show Back To Wheeling M city request Show Banana Boat Song M Belafonte Show Battle Hymn of the Republic M, S Patriotic Show Beautiful Ohio M Ohio state song Show Beautiful Dreamer S classic ballad Show Beep, Beep S/M/F 50's novelty tune Show Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) F fast Show Before The Parade Passes By S/F production number from HELLO DOLLY Show Belafonte Medley M Belafonte songs Show Bengals Fight Song F Bengals games Page 2 Don Gray Arrangements October, 2017 Tempo S= slow, freely Music M=medium, swing Category Title F=fast Description Show Biggest Aspidastra In The World S English music hall song Show Blow, Gabrial, Blow F -

Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Supplemental Guide

KINDERGARTEN Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Listening & Learning™ Strand Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Supplemental Guide Supplemental Read-Aloud Again!™ It Tell Farms Farms Supplemental Guide to the Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Listening & Learning™ Strand KINDERGARTEN Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

Let's Read: Early Years Literacy Toolkit for Public Libraries

1 Let’s Read! EARLY YEARS LITERACY TOOLKIT FOR PUBLIC LIBRARIES 2 Contents Raising Literacy Australia 4 Module 1: Planning your early childhood Where to begin 5 Evaluation 6 Know your material 7 Organise your props 8 Have everything ready, close at hand and in the order you will need it 9 Be prepared! 9 Share an activity 10 Enjoy what you do 10 Have realistic expectations 10 Supporting positive behaviour 11 Planning with themes 14 STEAM inspiration for sessions and programs 15 Sessions for different ages and stages 17 Module 2: Tools, tips and templates 22 Storytime book recommendations from library staff across Victoria 23 Storytime book recommendations by theme 26 Storytime session plan 31 Supporting positive behaviour: Preparation checklist 34 Tip sheet: Sharing information with families 35 Tip sheet: Milestones in child development 36 Tip sheet: Conversation starters 39 Tip sheet: Sing a song 40 Welcome songs and chants 41 3 If you’re happy and you know it 41 Five little speckled frogs 42 Old MacDonald had a farm 43 The grand old Duke of York 44 Open shut them 45 Twinkle, twinkle little star 46 Galumph, went the little green frog 47 Teddy bear, teddy bear 47 Row, row, row your boat 48 Incy Wincy Spider 49 Baby | Read every day 50 Baby | Sing every day 50 Baby | Talk every day 51 Baby | Play every day 52 Toddler | Read every day 53 Toddler | Sing every day 53 Toddler | Talk every day 54 Toddler | Play every day 55 Preschooler | Read every day 56 Preschooler | Sing every day 56 Preschooler | Talk every day 57 Preschooler | Play every day 58 Reading with school-age children 59 Speak to your child in your home language 60 Screen time for young children 61 The benefits of Storytime at the library 62 Online resources 63 4 We now know that the first years of a child’s life are vital to their development. -

Education Pack

Old MacDonald had a Farm EDUCATION PACK The People’s Theatre Company www.ptc.org.uk The People’s Theatre Company Old MacDonald had a Farm Education Pack TABLE OF CONTENTS About The People’s Theatre Company III More Stuff for Schools III Introduction IV Coverage of The National Curriculum (2014) V-VIII Summary of the Story 1 English Lesson 1 2-4 English Lesson 2 (Speaking & Listening) 5-6 Mathematics 7-9 Science 10-11 Geography 12-14 Computing 15-17 Resources 18-49 Songs to Sing 50-60 The People’s Theatre Company Old MacDonald had a Farm Education Pack About The People’s Theatre Company The People’s Theatre Company was set up to make quality theatre accessible to everyone. Our award winning shows have played to sell-out crowds up and down the country and each year the company brings that same standard of theatre into schools and youth groups to provide drama training, PPA cover and specialised workshops. If you would like details of any of these services please contact us at [email protected] Find out more about: The People’s Theatre Company , our past productions, workshops and ‘Old MacDonald had a Farm’ by visiting our website at www.ptc.org.uk. You can also email us directly at: [email protected] More Stuff for Schools The PTC is committed to its audience of young people and as part of that commitment we want drama to be available to everybody. To that end we are happy to provide schools and youth groups with affordable, quality drama training, PPA cover and specialised workshops. -

Download Booklet

www.champshillrecords.co.uk TRACK LISTING 1 A SONG FOR CHRISTMAS * Carroll Coates, arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 3’23 14 A FESTIVAL OF CAROLS IN TWO MINUTES Cantabile – The London Quartet 2’15 2 BETHLEHEM DOWN Bruce Blunt / Peter Warlock, arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 3’30 15 CHRISTMAS IN MY HEART * Rob Tyger / Kay Dennar, arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 4’15 OUR JOYFUL’ST FEAST * Christopher Steel, arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 16 SÜßER DIE GLOCKEN NIE KLINGEN * Traditional, arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 4’47 3 WHAT SWEETER MUSIC (HERRICK’S CAROL) Robert Herrick 2’24 17 INFANT HOLY, INFANT LOWLY Traditional / Edith M. G. Reed, arr. Willcocks 2’09 4 THERE WAS A TIME FOR SHEPHERDS Anthea Steel 1’32 5 A CHRISTMAS CAROL George Wither 1’47 18 QUELLE EST CETTE ODEUR AGRÉABLE ? Traditional, arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 3’25 6 THE TWELVE DAYS OF CHRISTMAS 2’47 19 THE WEXFORD CAROL * Traditional, arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 5’03 Traditional / Frederic Austin / Cantabile – The London Quartet, arr. Knight 20 CHRISTMAS CARDS Garth Bardsley / Ben Parry 3’13 7 I’LL BE HOME FOR CHRISTMAS * Kim Gannon / Walter Kent / Buck Ram, 4’06 arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 21 LET IT SNOW! LET IT SNOW! LET IT SNOW! * Sammy Cahn / Jule Styne, 2’46 arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 8 HAVE YOURSELF A MERRY LITTLE CHRISTMAS Hugh Martin / Ralph Blane, 2’14 arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 22 THE BIRDS Hilaire Belloc / Peter Warlock, arr. Cantabile – The London Quartet 1’23 9 GOOD KING WENCESLAS HAD A FARM * 1’53 23 NATIVITIE John Donne / Mark Fleming 2’17 Traditional / John Mason Neale / Thomas Helmore, arr.