The Principle of Stationary Action in Biophysics: Stability in Protein Folding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

Classical Mechanics

Classical Mechanics Hyoungsoon Choi Spring, 2014 Contents 1 Introduction4 1.1 Kinematics and Kinetics . .5 1.2 Kinematics: Watching Wallace and Gromit ............6 1.3 Inertia and Inertial Frame . .8 2 Newton's Laws of Motion 10 2.1 The First Law: The Law of Inertia . 10 2.2 The Second Law: The Equation of Motion . 11 2.3 The Third Law: The Law of Action and Reaction . 12 3 Laws of Conservation 14 3.1 Conservation of Momentum . 14 3.2 Conservation of Angular Momentum . 15 3.3 Conservation of Energy . 17 3.3.1 Kinetic energy . 17 3.3.2 Potential energy . 18 3.3.3 Mechanical energy conservation . 19 4 Solving Equation of Motions 20 4.1 Force-Free Motion . 21 4.2 Constant Force Motion . 22 4.2.1 Constant force motion in one dimension . 22 4.2.2 Constant force motion in two dimensions . 23 4.3 Varying Force Motion . 25 4.3.1 Drag force . 25 4.3.2 Harmonic oscillator . 29 5 Lagrangian Mechanics 30 5.1 Configuration Space . 30 5.2 Lagrangian Equations of Motion . 32 5.3 Generalized Coordinates . 34 5.4 Lagrangian Mechanics . 36 5.5 D'Alembert's Principle . 37 5.6 Conjugate Variables . 39 1 CONTENTS 2 6 Hamiltonian Mechanics 40 6.1 Legendre Transformation: From Lagrangian to Hamiltonian . 40 6.2 Hamilton's Equations . 41 6.3 Configuration Space and Phase Space . 43 6.4 Hamiltonian and Energy . 45 7 Central Force Motion 47 7.1 Conservation Laws in Central Force Field . 47 7.2 The Path Equation . -

Chapter 5 the Relativistic Point Particle

Chapter 5 The Relativistic Point Particle To formulate the dynamics of a system we can write either the equations of motion, or alternatively, an action. In the case of the relativistic point par- ticle, it is rather easy to write the equations of motion. But the action is so physical and geometrical that it is worth pursuing in its own right. More importantly, while it is difficult to guess the equations of motion for the rela- tivistic string, the action is a natural generalization of the relativistic particle action that we will study in this chapter. We conclude with a discussion of the charged relativistic particle. 5.1 Action for a relativistic point particle How can we find the action S that governs the dynamics of a free relativis- tic particle? To get started we first think about units. The action is the Lagrangian integrated over time, so the units of action are just the units of the Lagrangian multiplied by the units of time. The Lagrangian has units of energy, so the units of action are L2 ML2 [S]=M T = . (5.1.1) T 2 T Recall that the action Snr for a free non-relativistic particle is given by the time integral of the kinetic energy: 1 dx S = mv2(t) dt , v2 ≡ v · v, v = . (5.1.2) nr 2 dt 105 106 CHAPTER 5. THE RELATIVISTIC POINT PARTICLE The equation of motion following by Hamilton’s principle is dv =0. (5.1.3) dt The free particle moves with constant velocity and that is the end of the story. -

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM and ROTATIONS

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND ROTATIONS In classical mechanics the total angular momentum L~ of an isolated system about any …xed point is conserved. The existence of a conserved vector L~ associated with such a system is itself a consequence of the fact that the associated Hamiltonian (or Lagrangian) is invariant under rotations, i.e., if the coordinates and momenta of the entire system are rotated “rigidly” about some point, the energy of the system is unchanged and, more importantly, is the same function of the dynamical variables as it was before the rotation. Such a circumstance would not apply, e.g., to a system lying in an externally imposed gravitational …eld pointing in some speci…c direction. Thus, the invariance of an isolated system under rotations ultimately arises from the fact that, in the absence of external …elds of this sort, space is isotropic; it behaves the same way in all directions. Not surprisingly, therefore, in quantum mechanics the individual Cartesian com- ponents Li of the total angular momentum operator L~ of an isolated system are also constants of the motion. The di¤erent components of L~ are not, however, compatible quantum observables. Indeed, as we will see the operators representing the components of angular momentum along di¤erent directions do not generally commute with one an- other. Thus, the vector operator L~ is not, strictly speaking, an observable, since it does not have a complete basis of eigenstates (which would have to be simultaneous eigenstates of all of its non-commuting components). This lack of commutivity often seems, at …rst encounter, as somewhat of a nuisance but, in fact, it intimately re‡ects the underlying structure of the three dimensional space in which we are immersed, and has its source in the fact that rotations in three dimensions about di¤erent axes do not commute with one another. -

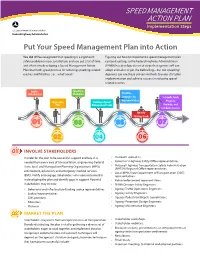

SPEED MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN Implementation Steps

SPEED MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN Implementation Steps Put Your Speed Management Plan into Action You did it! You recognized that speeding is a significant Figuring out how to implement a speed management plan safety problem in your jurisdiction, and you put a lot of time can be daunting, so the Federal Highway Administration and effort into developing a Speed Management Action (FHWA) has developed a set of steps that agency staff can Plan that holds great promise for reducing speeding-related adopt and tailor to get the ball rolling—but not speeding! crashes and fatalities. So…what’s next? Agencies can use these proven methods to jump start plan implementation and achieve success in reducing speed- related crashes. Involve Identify a Stakeholders Champion Prioritize Strategies for Set Goals, Track Implementation Market the Develop a Speed Progress, Plan Management Team Evaluate, and Celebrate Success Identify Strategy Leads INVOLVE STAKEHOLDERS In order for the plan to be successful, support and buy-in is • Outreach specialists. needed from every area of transportation: engineering (Federal, • Governor’s Highway Safety Office representatives. State, local, and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO), • National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) Regional Office representatives. enforcement, education, and emergency medical services • Local/MPO/State Department of Transportation (DOT) (EMS). Notify and engage stakeholders who were instrumental representatives. in developing the plan and identify gaps in support. Potential • Police/enforcement representatives. stakeholders may include: • FHWA Division Safety Engineers. • Behavioral and infrastructure funding source representatives. • Agency Traffic Operations Engineers. • Judicial representatives. • Agency Safety Engineers. • EMS providers. • Agency Pedestrian/Bicycle Coordinators. • Educators. • Agency Pavement Design Engineers. -

The Development of the Action Principle a Didactic History from Euler-Lagrange to Schwinger Series: Springerbriefs in Physics

springer.com Walter Dittrich The Development of the Action Principle A Didactic History from Euler-Lagrange to Schwinger Series: SpringerBriefs in Physics Provides a philosophical interpretation of the development of physics Contains many worked examples Shows the path of the action principle - from Euler's first contributions to present topics This book describes the historical development of the principle of stationary action from the 17th to the 20th centuries. Reference is made to the most important contributors to this topic, in particular Bernoullis, Leibniz, Euler, Lagrange and Laplace. The leading theme is how the action principle is applied to problems in classical physics such as hydrodynamics, electrodynamics and gravity, extending also to the modern formulation of quantum mechanics 1st ed. 2021, XV, 135 p. 23 illus., 1 illus. and quantum field theory, especially quantum electrodynamics. A critical analysis of operator in color. versus c-number field theory is given. The book contains many worked examples. In particular, the term "vacuum" is scrutinized. The book is aimed primarily at actively working researchers, Printed book graduate students and historians interested in the philosophical interpretation and evolution of Softcover physics; in particular, in understanding the action principle and its application to a wide range 54,99 € | £49.99 | $69.99 of natural phenomena. [1]58,84 € (D) | 60,49 € (A) | CHF 65,00 eBook 46,00 € | £39.99 | $54.99 [2]46,00 € (D) | 46,00 € (A) | CHF 52,00 Available from your library or springer.com/shop MyCopy [3] Printed eBook for just € | $ 24.99 springer.com/mycopy Order online at springer.com / or for the Americas call (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER / or email us at: [email protected]. -

Newtonian Mechanics Is Most Straightforward in Its Formulation and Is Based on Newton’S Second Law

CLASSICAL MECHANICS D. A. Garanin September 30, 2015 1 Introduction Mechanics is part of physics studying motion of material bodies or conditions of their equilibrium. The latter is the subject of statics that is important in engineering. General properties of motion of bodies regardless of the source of motion (in particular, the role of constraints) belong to kinematics. Finally, motion caused by forces or interactions is the subject of dynamics, the biggest and most important part of mechanics. Concerning systems studied, mechanics can be divided into mechanics of material points, mechanics of rigid bodies, mechanics of elastic bodies, and mechanics of fluids: hydro- and aerodynamics. At the core of each of these areas of mechanics is the equation of motion, Newton's second law. Mechanics of material points is described by ordinary differential equations (ODE). One can distinguish between mechanics of one or few bodies and mechanics of many-body systems. Mechanics of rigid bodies is also described by ordinary differential equations, including positions and velocities of their centers and the angles defining their orientation. Mechanics of elastic bodies and fluids (that is, mechanics of continuum) is more compli- cated and described by partial differential equation. In many cases mechanics of continuum is coupled to thermodynamics, especially in aerodynamics. The subject of this course are systems described by ODE, including particles and rigid bodies. There are two limitations on classical mechanics. First, speeds of the objects should be much smaller than the speed of light, v c, otherwise it becomes relativistic mechanics. Second, the bodies should have a sufficiently large mass and/or kinetic energy. -

Some Insights from Total Collapse

Some insights from total collapse S´ergio B. Volchan Abstract We discuss the Sundman-Weierstrass theorem of total collapse in its histor- ical context. This remarkable and relatively simple result, a type of stability criterion, is at the crossroads of some interesting developments in the gravi- tational Newtonian N-body problem. We use it as motivation to explore the connections to such important concepts as integrability, singularities and typ- icality in order to gain some insight on the transition from a predominantly quantitative to a novel qualitative approach to dynamical problems that took place at the end of the 19th century. Keywords: Celestial Mechanics; N-body problem; total collapse, singularities. I Introduction Celestial mechanics is one of the treasures of physics. With a rich and fascinating history, 1 it had a pivotal role in the very creation of modern science. After all, it was Hooke’s question on the two-body problem and Halley’s encouragement (and financial resources) that eventually led Newton to publish the Principia, a water- shed. 2 Conversely, celestial mechanics was the testing ground par excellence for the new mechanics, and its triumphs in explaining a wealth of phenomena were decisive in the acceptance of the Newtonian synthesis and the “clockwork universe”. arXiv:0803.2258v1 [physics.hist-ph] 14 Mar 2008 From the beginning, special attention was paid to the N-body problem, the study of the motion of N massive bodies under mutual gravitational forces, taken as a reliable model of the the solar system. The list of scientists that worked on it, starting with Newton himself, makes a veritable hall of fame of mathematics and physics; also, a host of concepts and methods were created which are now part of the vast heritage of modern mathematical-physics: the calculus, complex variables, the theory of errors and statistics, differential equations, perturbation theory, potential theory, numerical methods, analytical mechanics, just to cite a few. -

The Phase Space Elementary Cell in Classical and Generalized Statistics

Entropy 2013, 15, 4319-4333; doi:10.3390/e15104319 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy Article The Phase Space Elementary Cell in Classical and Generalized Statistics Piero Quarati 1;2;* and Marcello Lissia 2 1 DISAT, Politecnico di Torino, C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, Torino I-10129, Italy 2 Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Cagliari, Monserrato I-09042, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0706754899; Fax: +39-070510212. Received: 05 September 2013; in revised form: 25 September 2013/ Accepted: 27 September 2013 / Published: 15 October 2013 Abstract: In the past, the phase-space elementary cell of a non-quantized system was set equal to the third power of the Planck constant; in fact, it is not a necessary assumption. We discuss how the phase space volume, the number of states and the elementary-cell volume of a system of non-interacting N particles, changes when an interaction is switched on and the system becomes or evolves to a system of correlated non-Boltzmann particles and derives the appropriate expressions. Even if we assume that nowadays the volume of the elementary cell is equal to the cube of the Planck constant, h3, at least for quantum systems, we show that there is a correspondence between different values of h in the past, with important and, in principle, measurable cosmological and astrophysical consequences, and systems with an effective smaller (or even larger) phase-space volume described by non-extensive generalized statistics. -

Newton's Third Law (Lecture 7) Example the Bouncing Ball You Can Move

3rd Law Newton’s third law (lecture 7) • If object A exerts a force on object B, then object B exerts an equal force on object A For every action there is an in the opposite direction. equal and opposite reaction. B discuss collisions, impulse, A momentum and how airbags work B Æ A A Æ B Example The bouncing ball • What keeps the box on the table if gravity • Why does the ball is pulling it down? bounce? • The table exerts an • It exerts a downward equal and opposite force on ground force upward that • the ground exerts an balances the weight upward force on it of the box that makes it bounce • If the table was flimsy or the box really heavy, it would fall! Action/reaction forces always You can move the earth! act on different objects • The earth exerts a force on you • you exert an equal force on the earth • The resulting accelerations are • A man tries to get the donkey to pull the cart but not the same the donkey has the following argument: •F = - F on earth on you • Why should I even try? No matter how hard I •MEaE = myou ayou pull on the cart, the cart always pulls back with an equal force, so I can never move it. 1 Friction is essential to movement You can’t walk without friction The tires push back on the road and the road pushes the tires forward. If the road is icy, the friction force You push on backward on the ground and the between the tires and road is reduced. -

Chapter 04 Rotational Motion

Chapter 04 Rotational Motion P. J. Grandinetti Chem. 4300 P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 04: Rotational Motion Angular Momentum Angular momentum of particle with respect to origin, O, is given by l⃗ = ⃗r × p⃗ Rate of change of angular momentum is given z by cross product of ⃗r with applied force. p m dl⃗ dp⃗ = ⃗r × = ⃗r × F⃗ = ⃗휏 r dt dt O y Cross product is defined as applied torque, ⃗휏. x Unlike linear momentum, angular momentum depends on origin choice. P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 04: Rotational Motion Conservation of Angular Momentum Consider system of N Particles z m5 m 2 Rate of change of angular momentum is m3 ⃗ ∑N l⃗ ∑N ⃗ m1 dL d 훼 dp훼 = = ⃗r훼 × dt dt dt 훼=1 훼=1 y which becomes m4 x ⃗ ∑N dL ⃗ net = ⃗r훼 × F dt 훼 Total angular momentum is 훼=1 ∑N ∑N ⃗ ⃗ L = l훼 = ⃗r훼 × p⃗훼 훼=1 훼=1 P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 04: Rotational Motion Conservation of Angular Momentum ⃗ ∑N dL ⃗ net = ⃗r훼 × F dt 훼 훼=1 Taking an earlier expression for a system of particles from chapter 1 ∑N ⃗ net ⃗ ext ⃗ F훼 = F훼 + f훼훽 훽=1 훽≠훼 we obtain ⃗ ∑N ∑N ∑N dL ⃗ ext ⃗ = ⃗r훼 × F + ⃗r훼 × f훼훽 dt 훼 훼=1 훼=1 훽=1 훽≠훼 and then obtain 0 > ⃗ ∑N ∑N ∑N dL ⃗ ext ⃗ rd ⃗ ⃗ = ⃗r훼 × F + ⃗r훼 × f훼훽 double sum disappears from Newton’s 3 law (f = *f ) dt 훼 12 21 훼=1 훼=1 훽=1 훽≠훼 P. -

Newton's Third Law of Motion

ENERGY FUNDAMENTALS – LESSON PLAN 1.4 Newton’s Third Law of Motion This lesson is designed for 3rd – 5th grade students in a variety of school settings Public School (public, private, STEM schools, and home schools) in the seven states served by local System Teaching power companies and the Tennessee Valley Authority. Community groups (Scouts, 4- Standards Covered H, after school programs, and others) are encouraged to use it as well. This is one State lesson from a three-part series designed to give students an age-appropriate, Science Standards informed view of energy. As their understanding of energy grows, it will enable them to • AL 3.PS.4 3rd make informed decisions as good citizens or civic leaders. • AL 4.PS.4 4th rd • GA S3P1 3 • GA S3CS7 3rd This lesson plan is suitable for all types of educational settings. Each lesson can be rd adapted to meet a variety of class sizes, student skill levels, and time requirements. • GA S4P3 3 • KY PS.1 3rd rd • KY PS.2 3 Setting Lesson Plan Selections Recommended for Use • KY 3.PS2.1 3rd th Smaller class size, • The “Modeling” Section contains teaching content. • MS GLE 9.a 4 • NC 3.P.1.1 3rd higher student ability, • While in class, students can do “Guided Practice,” complete the • TN GLE 0307.10.1 3rd and /or longer class “Recommended Item(s)” and any additional guided practice items the teacher • TN GLE 0307.10.2 3rd length might select from “Other Resources.” • TN SPI 0307.11.1 3rd • NOTE: Some lesson plans do and some do not contain “Other Resources.” • TN SPI 0307.11.2 3rd • At home or on their own in class, students can do “Independent Practice,” • TN GLE 0407.10.1 4th th complete the “Recommended Item(s)” and any additional independent practice • TN GLE 0507.10.2 5 items the teacher selects from “Other Resources” (if provided in the plan).