UNIVERSITY of HARVARD, HOUGHTON LIBRARY, MS. Typ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Bayntun

QUITE A TRADITIONAL CATALOGUE - FROM AINSWORTH TO WHITMAN ebc e-catalogue 14 2016 George bayntun Manvers Street • Bath • BA1 1JW • UK 01225 466000 • [email protected] www.georgebayntun.com BOUND BY BAYNTUN IN TWO VOLUMES WITH 95 EXTRA PLATES 1. AINSWORTH (William Harrison). The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. Frontispiece, 39 plates and 55 vignettes by Cruikshank and extra-illustrated with 95 plates, some inlaid to size and a number captioned in manuscript. One volume bound in two. 8vo. [227 x 143 x 70 mm]. xiv, 276 pp; [1]f, 277-543 pp. Bound c.1920 by George Bayntun (signed with an ink pallet on front endleaves) in half dark green goatskin, lighter green cloth sides, the spines divided into six panels with gilt compartments, lettered in the second and fourth and at the foot, the others with foliate centres and corners and small circles, marbled endleaves, top edges gilt, the others untrimmed. (Spines slightly faded, edges foxed). [ebc4812] London: [printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co. for] George Routledge and Sons, [c.1880] £750 The Author's Copyright Edition. Occasional foxing but a good copy in a neat and well preserved pair of bindings (it is always good to see how well our handiwork has done). The 95 extra plates necessitated the additional volume. The plates are a selection of portraits and views, most of them relating directly to the novel and some of them rarer than others. ELIZABETH WHITBREAD'S COPY 2. [ALLESTREE (Richard)]. Private Devotions for Several Occasions, Ordinary and Extraordinary. 12mo. [161 x 93 x 14 mm]. -

Athena Rare Books

ATHENA RARE BOOKS CATALOG 6 Including Literature, Music, Science, History, Medicine, Psychology, Language, Women & Philosophy ATHENA RARE BOOKS 424 Riverside Drive, Fairfield CT 06824 USA phone: 203-254-2727 - fax: 203-254-3518 CATALOG 6 TABLE of CONTENTS Literature: pg. 1 Science: pg. 3 Medicine: pg. 6 Language: pg. 8 Music: pg. 3 History: pg. 5 Psychology: pg. 7 Women: pg. 9 Philosophy: pg. 12 LITERATURE “She Walks in Beauty Like the Night” – First Edition, Second Issue BYRON, Lord [George Gordon]. Hebrew Melodies, John Murray, London, 1815. 1 blank leaf + half-title + TP + 1 leaf = Prefacatory Note + [i]-[ii] = Contents + half title + [3]-53 + [55]-[56] = Advertisements + half-title for binding with other pamphlets, Octavo. First Edition, Second Issue. (Wise, Vol. 1., p. 104) $450 The second issue – without the announcement for Jacqueline in the ads and with the extended form of the ad for Campbell’s Selected Beauties. Containing the first edition of one of Byron’s most famous poems, She Walks in Beauty: She walks in beauty, like the night Of cloudless climes and starry skies… Along with one of his most stirring poems , The Destruction of Semnacherib: The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold… Modern maroon cloth with no lettering whatsoever on the outside. First blank leaf has been lightly creased but otherwise this is a lovely, uncut copy of one of Byron’s most desirable titles. “Two Roads Diverged in a Yellow Woods” – First Edition, First Printing FROST, Robert. Mountain Interval, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1916. -

Catalogue of Manuscripts in the Roth Collection’, Contributed by Cecil Roth Himself to the Alexander Marx Jubilee Volume (New York, 1950), Where It Forms Pp

Handlist 164 LEEDS UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Provisional handlist of manuscripts in the Roth Collection Introduction Dr Cecil Roth (1899-1970), the Jewish historian, was born on 5 March 1899 in Dalston, London, the youngest of the four sons of Joseph and Etty Roth. Educated at the City of London School, he saw active service in France in 1918 and then read history at Merton College, Oxford, obtaining a first class degree in modern history in 1922, and a DPhil in 1924; his thesis was published in 1925 as The Last Florentine Republic. In 1928 he married Irene Rosalind Davis. They had no children. Roth soon turned to Jewish studies, his interest from childhood, when he had a traditional religious education and learned Hebrew from the Cairo Genizah scholar Jacob Mann. He supported himself by freelance writing until in 1939 he received a specially created readership in post-biblical Jewish studies at the University of Oxford, where he taught until his retirement in 1964. He then settled in Israel and divided his last years between New York, where he was visiting professor at Queens’ College in City University and Stern College, and Jerusalem. He died in Jerusalem on 21 June 1970. Roth’s literary output was immense, ranging from definitive histories of the Jews both globally and in several particular countries, to bibliographical works, studies of painting, scholarly research, notably on the Dead Sea scrolls, and biographical works. But his crowning achievement was the editorship of the Encyclopaedia Judaica, which appeared in the year of his death. Throughout his life Roth collected both books and manuscripts, and art objects. -

A Preliminary Investigation Using EBSCO Online

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Evaluating Journal Aggregators: A Preliminary Investigation Using EBSCO Online. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2q61v8s5 Author Heyer-Gray, Bob Publication Date 2001 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Evaluating Journal Aggregators: A Preliminary Investigation Using EBSCO Online. Robert Heyer-Gray [[email protected]] Physical Sciences & Engineering Library University of California Davis, CA 95616 Introduction I initially began exploring the usefulness/usability of EBSCO Online [http://www-us.ebsco.com/online/] in March 2000. At that time, the database contained 141 journals listed as "On Subscription" for UC Davis. I reviewed our holdings again in November 2000 and once more in May 2001. 100 additional titles have been added to EBSCO Online for UC Davis since April 2000, and I would imagine that as more of the UC Davis subscriptions are transferred to EBSCO, that number would continue to expand. I approached EBSCO Online with a few questions in mind: 1. Is there anything unique to EBSCO Online? Or perhaps more precisely, are they providing access to publications (content) not already made available by other publisher agreements for UC Davis (UCD) and/or the California Digital Library (CDL)? 2. How did the holdings for title mounted on EBSCO Online compare to our print subscription in terms of coverage, completeness, and currency? 3. Can records (for both journals and individual articles) be linked to directly from an online catalog and/or A&I database? 4. What are the full-text formats? 5. How useful is EBSCO Online as an A&I/Full-Text database? Why UC Davis is Using EBSCO Online EBSCO Online provides access to full-text articles for journals to which the UCD Library subscribes through EBSCO Information Services. -

The Alfred Russel Wallace Correspondence Project's Transcription Protocol *Version 22.1*

The Alfred Russel Wallace Correspondence Project's Transcription Protocol *Version 22.1* Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 3 SETTING UP YOUR WORD PROCESSOR ............................................................... 3 WHAT DOCUMENTS DO WE TRANSCRIBE? ........................................................ 4 HOW TO FORMAT THE TRANSCRIBED TEXT ..................................................... 5 READING ORDER NUMBERS ............................................................................... 5 ACTUAL PAGE NUMBERS.................................................................................... 6 MULTIPLE LAYERS OF TEXT .............................................................................. 6 LETTER HEADER ................................................................................................... 7 1. Sender’s Address ............................................................................................... 7 2. Date .................................................................................................................... 9 SALUTATION (Greeting at beginning of letter) .................................................... 10 PARAGRAPHS ....................................................................................................... 10 SPACING ................................................................................................................ 10 TEXT IN THE MARGINS ..................................................................................... -

Said, Edward (1977) Orientalism. London: Penguin Noter Om Layor Ut: - Sidetall Øverst - Fotnoter Samlet I En Egen Seksjon Bakerst, Gruppert Etter Kapittel

Said, Edward (1977) Orientalism. London: Penguin Noter om layor ut: - Sidetall øverst - Fotnoter samlet I en egen seksjon bakerst, gruppert etter kapittel. Innholdsfortegnelse i word Said, Edward (1977)) Orientalism. London: Penguin ............................ 1 Innholdsfortegnelse i word..................................................................... 1 Contents.................................................................................................. 5 Preface (2003) ........................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgments................................................................................ 16 Introduction .......................................................................................... 18 I ......................................................................................................... 18 II........................................................................................................ 21 III....................................................................................................... 25 Chapter 1. The Scope of Orientalism.............................................. 43 I Knowing the Oriental................................................................. 43 II Imaginative Geography and Its Representations: Orientalizing the Oriental.............................................................................................. 59 III Projects........................................................................................ -

THE ROLE of SEMITIC CATCHWORDS in INTERPRETING the EPISTLE of JAMES Daniel K

Tyndale Bulletin 70.2 (2019) 245-267 THE ROLE OF SEMITIC CATCHWORDS IN INTERPRETING THE EPISTLE OF JAMES Daniel K. Eng ([email protected]) Summary This article examines the arrangement of the Epistle of James in light of Semitic documents that display catchword association. James shows evidence of being a compilation, with adjacent sections frequently connected by a common cognate. After identifying patterns of catchword association in the Hebrew Bible, LXX, and Qumran, the article identifies instances of catchword association in the Epistle of James. Finally, some conclusions are drawn for James, including recommendations about the study of its genre, provenance, structure, and interpretation.1 1. Introduction This article examines the interpretation of the Epistle of James in light of Semitic documents that display catchword association. James shows evidence of having adjacent sections frequently connected by a common cognate, called a catchword, or Stichwort. While not necessarily displaying logical progression, the epistle shows consistency with an intentional Semitic custom of connecting material by catchword. After identifying patterns of catchword association in Jewish documents, we will examine similar arrangements in James and 1 Earlier versions of this article were presented at the Oxford-Cambridge Biblical Studies Conference, the British New Testament Conference, and the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting, all in 2018. The author would like to thank those who gave helpful advice and feedback, especially K. Lawson Younger Jr., C. Hassell Bullock, J. LaRae Ferguson, David A. deSilva, Darian Lockett, Andrew Yee, and Jonathan Robinson. 246 TYNDALE BULLETIN 70.2 (2019) offer recommendations on how the identification of catchword association impacts the interpretation of the epistle. -

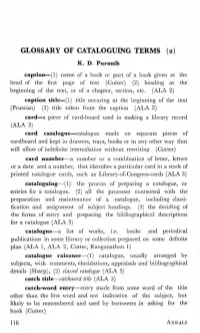

Glossary of Cataloguing Terms (2)

GLOSSARY OF CATALOGUING TERMS (2) K. D. Puranik caption-(l) name of a book or part of a book grven at the head of the first page of text (Cutter) (2) heading at the beginning of the text, or of a chapter, section, etc. (ALA 2) caption title-(l) title occuring at the beginning of the text (Prussian) (2) title taken from the caption (ALA 2) card-a piece of card-board used in making a library record (ALA 3) card catalogue-catalogue made on separate pieces of cardboard and kept in drawers, trays, books or in any other way that will allow of indefinite intercalation without rewriting (Cutter) card nu:rnber-a number or a combination of letter, letters or a date and a number, that identifies a particular card in a stock of printed catalogue cards, such as Library-of-Congress-cards (ALA 3) cataloguing-( 1) the process of preparing a catalogue, or entries for a catalogue. (2) all the processes connected with the preparation and maintenance of a catalogue, including classi- fication and assignment of subject headings. (3) the deciding of the forms of entry and preparing the bibliographical descriptions for a catalogue (ALA 3) catalogue-a list of works, i.e, books and periodical publications in some library or collection prepared on some definite plan (ALA 1, ALA 2, Cutter, Ranganathan 1) catalogue l'aisonee-(l) catalogue, usually arranged by subjects, with comments, elucidations, appraisals and bibliographical details (Sharp), (2) classed catalogue (ALA 3) catch title-catchword title (ALA 3) catch-word entry-entry made from some word of the title other than the first word and not indicative of the subject, but likely to be remembered and used by borrowers in asking for the book (Cutter) 116 ANNALS JUNE 1954 GLOSSARY OF CATALOGUTNG TERMS (2) catch-word reference-same as catch-word entry omitting the imprint and referring (Cutter) catchword title-a partial title consistmg of some striking or easily remembered word or phrase. -

Glossary of Terms for Pre-Industrial Book History

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Library Faculty & Staff Publications Libraries 7-2009 Glossary of terms for pre-industrial book history Richard W. Clement Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/lib_pubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Clement, Richard W., "Glossary of terms for pre-industrial book history" (2009). Library Faculty & Staff Publications. Paper 11. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/lib_pubs/11 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty & Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Glossary 7/6/09 10:48 AM GLOSSARY OF TERMS FOR PRE-INDUSTRIAL BOOK HISTORY Richard W. Clement Utah State University Addendum / Addenda - addition / additions to the book after it has been printed. Bifolium - two conjugate leaves; a sheet prepared for writing or having been written on. Biting - the fusion of two strokes in two different letters, woven together in textura. Black-letter type - gothic or textura type. Boards - the wood, paste-board, straw-board, or other base for the sides of any bound or cased book, i.e. any book in hard covers. Body of the type - the height of the letter (or point size). Boss - metal knobs used to protect the surface of the leather sides of the binding. Bound - A book in which the gatherings are sewn onto horizontal cords, the free ends of which are then drawn through holes in the board and firmly attached so that leaves and binding become a structural entity. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Welcome to the Department of English and Creative Writing __________________________________ 2 New Courses ___________________________________________________________________________ 4 Course Descriptions _____________________________________________________________________ 5 Major and Minor Requirements __________________________________________________________ 33 Honors _______________________________________________________________________________ 35 Directions for Sophomores Planning to Major in English or English and Creative Writing ________ 36 People: English Department Administration ___________________________________________________ 37 Faculty Bios ________________________________________________________________________ 38 May 9, 2020 Department of English & Creative Writing 2020-21 2 Welcome to the Department of English and Creative Writing! English as a discipline stresses the intensive study of writers and their works in literary, cultural, and historical contexts. It is keyed to the appreciation and analysis of literary language, through which writers compose and organize their poems, stories, novels, plays, and essays. The discipline equally stresses writing critically and creatively in response to reading literature. We thus offer a wide range of courses: introductory courses in literary and writing skills; more advanced courses in influential writers, historical periods, and themes in English, American, and world literatures in English; and numerous courses in creative writing, including screenwriting -

The Library of Robert Ball: Part Ii

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD. 40 SOUTH AUDLEY ST, LONDON W1K 2PR Tel: +44 (0)20-7297 4888 Fax: +44 (0)20-7297 4866 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank plc, 50 Pall Mall, P.O. Box 15162, London SW1A 1QB Sort code: 20-65-82 Swift code: BARCGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB98 BARC 206582 10511722 Euro account: IBAN: GB30 BARC 206582 45447011 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB46 BARC 206582 63992444 VAT number: GB 840 1358 54 MasterCard, Visa, and American Express accepted Recent Catalogues: 1433 English Books and Manuscripts 1432 Continental Books 1431 Travel & Exploration, Natural History Recent Lists: 2016/1 Human Sciences 2015/9 Early Drama 2015/8 Flora and Fauna 2015/7 Classics 2015/6 Design and Interiors 2015/5 Library of Robert Ball, Part I List 2016/2 Cover image from item 57. © Bernard Quaritch 2016 FROM THE LIBRARY OF ROBERT BALL: PART II English Literature 1500-1900, an American Journalist’s Collection Collecting rare books is a selfish pastime. It is about possession, about ownership. After all, the texts are universally available. Even the books themselves are often accessible in public libraries. But that is not the same as having them in one’s own bookcase. I have been an active collector for most of a long life. Now, in my 90th year, I have decided it is time to pass my pleasure on to others. Robert Ball 1) AUBREY, John. Miscellanies, viz. I. Day-Fatality. II. Local-Fatality. III. Ostenta. IV. Omens. V. Dreams. VI. Apparitions. VII. Voices. -

2020 Holiday Catalogue

1 TERMS Full descriptions are available upon request. Items for any reason unsatisfactory may be returned within ten days. HERITAGE BOOK SHOP 324 South Beverly Drive, Box 1421. Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Telephone 310.659.3674 [email protected] www.heritagebookshop.com Open By Appointment Only Front Cover Image: Item 44. [ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA]. Encyclopædia Britannica; or, A Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. Compiled upon a New Plan. In which the different sciences and arts are digested into distinct treatises or systems; and the various technical terms, &c. are explained as they occur in the order of the alphabet. Illustrated with one hundred and sixty copperplates. By a Society of Gentlemen in Scotland. In three volumes. London: Printed for John Donaldson, 1773. Back Cover Image: Item 33. DICKENS, Charles. A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. With Illustrations by John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843. 2 In Regards to the Controversial Presidential Election of 1824 1. [ADAMS, John Quincy]. [SOMERVILLE, William]. Suggestions on Presidential Elections, With Particular Reference to a Letter of William C. Somerville, Esq. Boston: Cummings, Hilliard & co., 1825. First edition of pamphlet attributed to John Quincy Adams in support of a letter that was written by Willam Somerville regarding the need to reform the presidential election system in the United States, following the controversial election of 1824. Octavo (8 x 5 1/4 inches; 204 x 133 mm). 32 pp. Pamphlet, disbound with stab-marks present. Some mild toning, mainly to final leaf. Overall a very good copy. HBS 68256. $850 Legal Pamphlet Attempting to Examine the Legal and Constitutional Basis For the 14th Amendment 2.