The Hegemony of Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Udaipur City

Journal of Global Resources Volume 4 January 2017 Page 99-107 ISSN: 2395-3160 (Print), 2455-2445 (Online) 13 SPATIO-TEMPORAL LANDUSE CHANGE: A CASE STUDY OF UDAIPUR CITY Barkha Chaplot Guest Faculty, Department of Geography, Mohanlal, Sukhadia University, Udaipur Email: [email protected] Abstract: The present research work attempts to examine the growth and development, trends and pattern of landuse of Udaipur city. The entire study is based on secondarysources of data. The growth and development of Udaipur city have been discussed in terms of expansion of the city limits from walled city to the present municipal boundary over the two periods of times i.e. pre-independence and post-independence period. However, the trends land use of the city has been examined for four periods of times from 1971 to 2011 and pattern of land use of the city has been analyzed for 2011. The study reveals that there is significant rise in land use in the categories of residential, commercial, industrial, institutional, entertainment, public and semi-public, circulation, the government reserved, agriculture, forest, water bodies, other open areas. Key words: Growth, Development, Land use, Spatio-Temporal, Growth Introduction Land is the most significant of all the natural resources and the human-use of land resources gives rise to land use. Land use varies with the man’s activity on land or purpose for which the land is being used, whether it is for food production, provision of shelter, recreation and processing of materials and so on, as well as the biophysical characteristics of the land itself. The land use is being shaped under the influence of two broad set of forces viz. -

Final Electoral Roll / Voter List (Alphabetical), Election - 2018

THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL / VOTER LIST (ALPHABETICAL), ELECTION - 2018 [As per order dt. 14.12.2017 as well as orders dt.23.08.2017 & 24.11.2017 Passed by Hon'ble Supreme Court of India in Transfer case (Civil) No. 126/2015 Ajayinder Sangwan & Ors. V/s Bar Council of Delhi and BCI Rules.] AT UDAIPUR IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP LOCATION OF POLLING STATION :- BAR ROOM, JUDICIAL COURTS, UDAIPUR DATE 01/01/2018 Page 1 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Electoral Name as on the Roll Electoral Name as on the Roll Number Number ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ ' A ' 77718 SH.AADEP SINGH SETHI 78336 KUM.AARTI TAILOR 67722 SH.AASHISH KUMAWAT 26226 SH.ABDUL ALEEM KHAN 21538 SH.ABDUL HANIF 76527 KUM.ABHA CHOUDHARY 35919 SMT.ABHA SHARMA 45076 SH.ABHAY JAIN 52821 SH.ABHAY KUMAR SHARMA 67363 SH.ABHIMANYU MEGHWAL 68669 SH.ABHIMANYU SHARMA 56756 SH.ABHIMANYU SINGH 68333 SH.ABHIMANYU SINGH CHOUHAN 64349 SH.ABHINAV DWIVEDI 74914 SH.ABHISHEK KOTHARI 67322 SH.ABHISHEK PURI GOSWAMI 45047 SMT.ADITI MENARIA 60704 SH.ADITYA KHANDELWAL 67164 KUM.AISHVARYA PUJARI 77261 KUM.AJAB PARVEEN BOHRA 78721 SH.AJAY ACHARYA 76562 SH.AJAY AMETA 40802 SH.AJAY CHANDRA JAIN 18210 SH.AJAY CHOUBISA 64072 SH.AJAY KUMAR BHANDARI 49120 SH.AJAY KUMAR VYAS 35609 SH.AJAY SINGH HADA 75374 SH.AJAYPAL -

Shikar Paintings : Contemporary Then, Traditional Now

ISSN 2319-5339 IISUniv.J.A. Vol.5(1), 45-51 (2016) Shikar Paintings : Contemporary Then, Traditional Now Yamini Sharma ABSTRACT This article traces the development of court painting at Mewar and tries to re- read the paintings in royal collection with an eye of a contemporary artist, working in Mewar School medium. This tries to establish the fact that miniatures in Mewar were beyond intricate details and decoration. They were very intellectually composed narratives of the Maharana’s life and hunt scenes. This article also extends the understanding of terms ‘contemporary’ and ‘tradition’ with respect to miniatures. As one can see the degradation of style of painting from court times into the now –a- day’s bazaar, outside the palace, the whole experience of going through museum collection and understanding the painting tradition falls flat when we see bad copies in bazaar. My research article lies there, why and how we got here? Keywords : Mewar Painting, Shikar Painting ( Hunting Scenes), Contemporary, Traditional, Bazaar Art Shikar paintings in City Palace Museum, Udaipur - An analysis into the contemporary world then, traditional now. The city palace museum was founded by the late Maharana Bhagwat Singh in 1969, while its Zenana Mahal section, in former women’s quarters of the palace, was opened in 1974. Few decades had passed since then the dissolution of the princely states after Indian Independence in 1947 and the death a few years later of Bhupal Singh, the last reigning Maharana of Mewar (b.1884, r.1930-55). In this period much of the old order has ineluctably passed away. -

Life Story of Maharana Pratap August 2017 Savior of Liberty and Self-Respect

Life Story of Maharana Pratap August 2017 Savior of Liberty and self-respect, ‘Hindua Suraj’ - Maharana Pratap ‘Shesha naag sir sehas paye, dhar rakhi khud aap, Ik bhala ri nok pai, thay dhabi partap!’ – Ram Singh Solanki Meaning: Shesh –the remainder, that which remains when all else cease to exist. Naag - Serpent. Shesha Naag is said to hold the planets of the universe on his hoods. He has to use his thousand hoods to protect and stabilize the unstable earth. But, Oh Pratap! You stabilized and protected the entire motherland, solely on the tip of your spear. Where the Snake God held the Earth on its thousands of heads; there, Oh! Brave Maharana Pratap, you have not only held your land on the tip of your spear but also used the strength of your spears to protect it. Maharana Pratap was the hundred and fourth heir of the great Sun dynasty ‘Suryavansh’. The Kings of erstwhile India were divided into two dynastic categories namely ‘Suryavanshi’ and ‘Chandravanshi’ based on the Sun and Moon Gods respectively. Mythological texts and manuscripts also refer to these two dynasties in which the ‘Suryavanshi’ Kings hold greater significance. This ‘Suryavansh’ dynasty was later known as ‘Rughavansh’ dynasty tracing its ancestry to ‘Surya’ the Sun God. The incarnation of Lord Rama, destroyer of the malevolent demon Ravana also occurred in the ‘Suryavanshi’ dynasty and it is believed that the Kingdom of Mewar originated from Luv, the elder son of Rama. This dynastic tradition continued with the birth of the popular King Guhaditya/Guhil in 568 CE and the dynasty was thus referred to as ‘Guhilvansh’/’Guhilot’ with ‘Rawal’ as its title. -

LOST TIGERS PLUNDERED FORESTS: a Report Tracing the Decline of the Tiger Across the State of Rajasthan (1900 to Present)

LOST TIGERS PLUNDERED FORESTS: A report tracing the decline of the tiger across the state of Rajasthan (1900 to present) By: Priya Singh Supervised by: Dr. G.V. Reddy IFS Citation: Singh, P., Reddy, G.V. (2016) Lost Tigers Plundered Forests: A report tracing the decline of the tiger across the state of Rajasthan (1900 to present). WWF-India, New Delhi. The study and its publication were supported by WWF-India Front cover photograph courtesy: Sandesh Kadur Photograph Details: Photograph of a mural at Garh Palace, Bundi, depicting a tiger hunt from the Shikarburj near Bundi town Design & Layout: Nitisha Mohapatra-WWF-India, 172 B, Lodhi Estate, New Delhi 110003 2 Table of Contents FOREWORD 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 INTRODUCTION 11 STATE CHAPTERS 26 1. Ajmer................................................................................................................28 2. Alwar.................................................................................................................33 3. Banswara...........................................................................................................41 4. Bharatpur..........................................................................................................45 5. Bundi.................................................................................................................51 6. Dholpur.............................................................................................................58 7. Dungarpur.........................................................................................................62 -

Printpdf/Rajasthan-Public-Service-Commission-Rpsc-Gk-State-Pcs-English

Drishti IAS Coaching in Delhi, Online IAS Test Series & Study Material drishtiias.com/printpdf/rajasthan-public-service-commission-rpsc-gk-state-pcs-english Rajasthan Public Service Commission (RPSC) GK Rajasthan GK Formation 1 November, 1956 Capital Jaipur Population 6,85,48,437 (8th in country) Area 3,42,239 Sm. Total District 33 Ancient name of State Marukantar, Rajputana Shape of State Quadrilateral (Kiteboarder) High Court Jodhpur 1/24 State Symbol State animal : Chinkara 2/24 State bird : Godavan State domestic animal : Camel State tree : Khejri State flower : Rohida 3/24 State folk dance : Ghoomar Rajasthan : General Information Total Division – 7 (Jaipur, Jodhpur, Ajmer, Kota, Udaipur, Bikaner and Bharatpur) State Sports of Rajasthan – Basketball Folk dance of Rajasthan – Ghoomar State legislature – Unicameral (Assembly) RajyaSabha seat – 10 Lok Sabha seat – 25 (SC-4, ST-3) State Assembly Seat – 200 First Speaker of Rajasthan Legislative Assembly – Narottam Lal Joshi First Deputy Speaker of Rajasthan Legislative Assembly – Lal Singh Shaktawat First Leader of Opposition of Rajasthan Legislative Assembly – Jaswant Singh First Protem Speaker of Rajasthan Legislative Assembly – Maharao Sangram Singh First Chief Minister of Rajasthan – Tikaram Paliwal The first woman MP of Rajasthan – Smt. Sharda Bhargava (Rajya Sabha) First woman Lok Sabha member of Rajasthan – Maharani Gayatri Devi The first Rajasthani nominated to the Rajya Sabha – Dr. Narayan Singh Most frequently elected Rajya Sabha members from the state – Ram Niwas Mirdha and Jaswant Singh (4-4 times) Most frequently elected woman Rajya Sabha member from the state – Smt. Sharda Bhargava (3 times) First woman Lok Sabha member of Scheduled Caste from the state – Usha Meena (Sawai Madhopur) 4/24 The first woman Lok Sabha member of Scheduled Tribe from the state – Smt. -

Julie Hughes, “Environmental Status and Wild Boar in Princely India,” in K

PPPRESERVED TTTIGER ,,, PPPROTECTED PPPANGOLIN ,,, DDDISPOSABLE DDDHOLE ::: WILDLIFE AND WILDERNESS IN PPPRINCELY IIINDIA Julie E. Hughes [email protected] On 28 June 2008 in the middle of the monsoon, an Indian Air Force helicopter delivered its cargo—a tranquilized adult male tiger dubbed ST-1 and a party of wildlife experts—into the heart of Sariska Tiger Reserve. Hailed by the Chief Wildlife Warden of Rajasthan as a scientifically planned “wild-to-wild relocation” unlike any before, ST-1’s involuntary flight over 200 km north from his established territory in Ranthambore National Park to a “key tiger habitat” compromised by poachers and notoriously devoid of tigers since 2004 was, in fact, well-precedented.1 In what may have been the world’s first attempted reintroduction of the animal, the Maharawal of Dungarpur translocated tigers to his jungles from Gwalior State between 1928 and 1930. 2 The Maharaja of Gwalior, in turn, made history when he imported, acclimatized, and released African lions in his territories ten years before. 3 Their actions largely forgotten today, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century princes regularly trapped and moved tiger, leopard, bear, and wild boar between jungle beats, viewing arenas, private menageries, and zoological gardens. International and domestic pressure to “Save the Tiger,” the economics of tourism and ecosystem services, and popular constructions of national pride and natural heritage help account for the relocation of ST-1 and seven additional tigers to Sariska as of January 2013, with -

Indian Culture & Heritage

1 Chapter-1 Culture and Heritage: The Concept We all know that when we hear or say 'culture', we think of the food habits, life style, dress, tradition, customs, language, beliefs and sanskaras. Have you ever thought that human being has made an astonishing progress in various spheres of life whether it is language culture, art or architecture or religion. Have you ever wondered as to how it happened? Definitely, because we did not have to make a fresh start every time but we could go forward and reconstruct on achievements accomplished by our ancestors. All the aspects of life like language, literature, art, architecture, painting, music, customs traditions, laws have come to us as heritage from our ancestors. Then, you add something new to it and make it rich for the coming generations. It is a constant and never ending process. Man possesses unique characteristic from the beginning known as culture. Every nation, country and region has its own culture. Culture denotes the method with which we think and act. It includes those things as well which we have received in inheritance being a member of this society. Art, music literature, craft, philosophy, religion and science are all part of culture, though it also incorporates customs, traditions, festivals, way of living and one's own concept on various aspects of life. All the achievements of a human being can be termed as culture. 1.0 Aims:- After studying this chapter you will be able to:- • Know about meaning and concept of culture. • Acquaint youself with general characteristics of culture. -

136 CHAPTER 4 MODERN BHILWARA the Objects of This Particular Section of This Present Chapter Are to Describe Economic and Social

136 CHAPTER 4 MODERN BHILWARA The objects of this particular section of this present chapter are to describe economic and social developments which have occurred since 1947, to contrast the social structure of the town as it existed at the time of India's transition to self-government and to trace and describe the various influences which have contributed to the process of change over the past quarter-century with special concentration to the structure of economic activity as it has related to the emergence of a definitive labour force. A picture of Bhilwara's demographic, commercial, religious and educational characteristics, as they were shortly before Independence, can be ascertained from Table 4. DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE Table 5 displays the population variations occurring in Bhilwara District and its "metropolitical" centre over the last 80 years. Today, out of 26 Rajasthan districts, Bhilwara District ranks as eleventh in size of population. Although the district's population has grown by 271% since 1901, it still only comprises some 30, (approximately) of Rajasthan's total population, which was 10.5 million (approximately) in 1901 and 34.1 million in 1981: While Bhilwara District's growth rate over this 80 year interval was Rajasthan's eighth largest (Rajasthan's overall growth was 328.6%), it should be noted that this rate has continually exceeded the national Table 4 Bhilwara Tahsil - Population, commercial and educational characteristics, 1941 Urban Rural Khalsa Khalsa Thikana Bhilwara Pur Sanganer 138 estates app. Total M F M F M F M F Persons Population by religion: Hindu 5,873 5,282 2,334 2,195 1,057 1,068 30,237 28,717 76,663 Muslim 1,767 1,631 360 311 334 316 361 324 5,404 Jain 493 430 274 234 38 30 84 76 1,659 Total 8,133 7,343 2,868 2,740 1,429 1,414 30,682 29,117 83,726 18.48 10.10 28.58 71.42 100 No. -

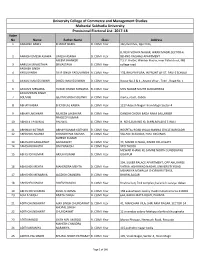

University College of Commerce and Management Studies Mohanlal

University College of Commerce and Management Studies Mohanlal Sukhadia University Provisional Electoral List- 2017-18 Voter No Name Father Name Class Address 1 AAKARSH BABEL BHARAT BABEL B. COM I Year 19c,civil lines, tiger hills, 8, NEW VIDHYA NAGAR, HIRAN MAGRI,SECTOR-4, 2 AAKASH UMESH ASAWA UMESH ASAWA B. COM I Year BEHIND VAISHALI APARTMENT ASEEM SHANKER T.S.V. Hostel, Warden House, near Fateschool, MB 3 AARUSH SRIVASTAVA SRIVASTAVA B. COM I Year college road AASHISH SINGH 4 YADUVANSHI DILIP SINGH YADUVANSHI B. COM I Year 178, BHOPALPURA, IN FRONT OF ST. PAULS SCHOOL 5 AAYUSH MAHESHWARI DINESH MAHESHWARI B. COM I Year House No.3 & 4 , Anand Vihar , Tekri , Road No. 1 6 AAYUSHI MENARIA HUKMI CHAND MENARIA B. COM I Year SHIV NAGAR SOUTH SUNDARWAS AAYUSHMAN SINGH 7 SOLANKI JEEVAN SINGH SOLANKI B. COM I Year merta, road , dabok 8 ABHAY KABRA BHERU LAL KABRA B. COM I Year 1227 Adarsh Nagar Hiran Magri Sector-4 9 ABHAY LAKSHKAR MUKESH LAKSHKAR B. COM I Year GANDHI CHOUK BADA NAKA SALUMBER PRADEEP KUMAR 10 ABHIJEET PALIWAL PALIWAL B. COM I Year H. NO 6,SURANO KE SEHRI,MALDAS STREET 11 ABHINAV KOTHARI ABHAY KUMAR KOTHARI B. COM I Year HOSPITAL ROAD JHALA MANNA CIRCLE BARISADRI 12 ABHISHEK ANJANA GHANSHYAM ANJANA B. COM I Year VILLAGE KESUNDA, POST KESUNDA SURESH KUMAR 13 ABHISHEK GANGAWAT GANGAWAT B. COM I Year 44, MANDI KI NAAL, INSIDE DELHI GATE 14 ABHISHEK KHATIK OM PRAKASH B. COM I Year VPO THOOR MEWAD KHANIJ KE SAMNE NORTH SUNDERWAS 15 ABHISHEK KUMAR ARJUN KUMAR B. -

Canadian Cialis Pharmacy

© Mapin Publishing Above: A painting at Shambhu Niwas Palace from 1905 CE shows Maharana Fateh Singh (r. 1884–1930 Ce) receiving his son Maharaj Kumar Bhupal Singh Right: Maharana Bhupal Singh (r. 1930–1955 CE) holding court under a tent, with his son Maharaj Kumar Bhagwat Singh seated near him Accession No. 2008.07.0175 Facing page: Shriji Arvind Singh Mewar with his son Lakshyaraj Singh Mewar at the Holika Dahan SHRIJI ARVIND SINGH MEWAR ceremony at Manek Chowk, The City Palace, WITH HIS SON Udaipur, on 3 March 2007 LAKSHYARAJ SINGH MEWAR 18 Rolls Royce GLK 21 Final.indd 18-19 31/07/12 11:57 AM Historical Perspective Rolls-Royce (RR) motorcars and India have enjoyed a very long and close association. This relationship dates back to the early 20th century and the era of Maharajas and the British rule in India, and it would not be wrong to say that if Rolls-Royce is today perhaps the most honoured luxury marque in the history of the automobile, it owes it to India. This is because the Indian subcontinent was the ultimate destination for many of Rolls-Royce’s early cars, as the Indian Maharanas and Maharajas were only too happy to make the transition from horse-drawn carriages to a horseless one. In 1907, an English businessman brought the first Rolls-Royce to India. It was christened the ‘Pearl of the East’ and participated in a 620-mile Reliability Trial, spread over six mountain passes. The Rolls-Royce performed brilliantly and after winning many awards, it was sold to the Maharaja of Gwalior. -

Copyright by Julie Elaine Hughes 2009

Copyright by Julie Elaine Hughes 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Julie Elaine Hughes certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Animal Kingdoms: Princely Power, the Environment, and the Hunt in Colonial India Committee: Gail Minault, Supervisor Cynthia Talbot William Roger Louis Syed Akbar Hyder Janet Davis Michael Charlesworth Animal Kingdoms: Princely Power, the Environment, and the Hunt in Colonial India by Julie Elaine Hughes, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2009 Acknowledgments Research for this dissertation could not have been completed without the generous support of an American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS) Junior Research Fellowship for 2007-08. I would like to thank everyone at the AIIS offices in Delhi and Chicago. I am also grateful to my affiliating institution in India, the Jawaharlal Nehru University, and to Dr. Neeladri Bhattacharya and Dr. Indivar Kamtekar at JNU’s Centre for Historical Studies. In India, I completed my research at the National Archives of India and the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts in Delhi; at the Rajasthan State Archives in Bikaner; at the Rajasthan State Archives Intermediary Depository, the Pratap Shodh Pratisthan, the Maharana Mewar Special Library, and the Saraswati Bhavan Pustakalaya in Udaipur; at the Old Secretariat archives, the Banganga Marg library, and the State Museum library under the Madhya Pradesh Directorate of Archeology, Archives, and Museums in Bhopal; and at the Uttar Pradesh State Archives in Lucknow.