Patterns for the Game of Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Combinatorial Game Theoretic Analysis of Chess Endgames

A COMBINATORIAL GAME THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF CHESS ENDGAMES QINGYUN WU, FRANK YU,¨ MICHAEL LANDRY 1. Abstract In this paper, we attempt to analyze Chess endgames using combinatorial game theory. This is a challenge, because much of combinatorial game theory applies only to games under normal play, in which players move according to a set of rules that define the game, and the last player to move wins. A game of Chess ends either in a draw (as in the game above) or when one of the players achieves checkmate. As such, the game of chess does not immediately lend itself to this type of analysis. However, we found that when we redefined certain aspects of chess, there were useful applications of the theory. (Note: We assume the reader has a knowledge of the rules of Chess prior to reading. Also, we will associate Left with white and Right with black). We first look at positions of chess involving only pawns and no kings. We treat these as combinatorial games under normal play, but with the modification that creating a passed pawn is also a win; the assumption is that promoting a pawn will ultimately lead to checkmate. Just using pawns, we have found chess positions that are equal to the games 0, 1, 2, ?, ", #, and Tiny 1. Next, we bring kings onto the chessboard and construct positions that act as game sums of the numbers and infinitesimals we found. The point is that these carefully constructed positions are games of chess played according to the rules of chess that act like sums of combinatorial games under normal play. -

1999/6 Layout

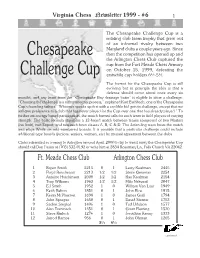

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

Combinatorics on the Chessboard

Combinatorics on the Chessboard Interactive game: 1. On regular chessboard a rook is placed on a1 (bottom-left corner). Players A and B take alternating turns by moving the rook upwards or to the right by any distance (no left or down movements allowed). Player A makes the rst move, and the winner is whoever rst reaches h8 (top-right corner). Is there a winning strategy for any of the players? Solution: Player B has a winning strategy by keeping the rook on the diagonal. Knight problems based on invariance principle: A knight on a chessboard has a property that it moves by alternating through black and white squares: if it is on a white square, then after 1 move it will land on a black square, and vice versa. Sometimes this is called the chameleon property of the knight. This is related to invariance principle, and can be used in problems, such as: 2. A knight starts randomly moving from a1, and after n moves returns to a1. Prove that n is even. Solution: Note that a1 is a black square. Based on the chameleon property the knight will be on a white square after odd number of moves, and on a black square after even number of moves. Therefore, it can return to a1 only after even number of moves. 3. Is it possible to move a knight from a1 to h8 by visiting each square on the chessboard exactly once? Solution: Since there are 64 squares on the board, a knight would need 63 moves to get from a1 to h8 by visiting each square exactly once. -

Kolov LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS an INVESTMENT in CHESS Po~;T;On No

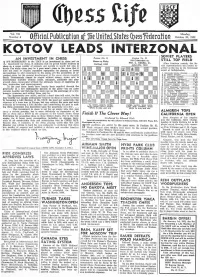

Vol. Vll Monday; N umber 4 Offjeitll Publication of me Unttecl States (bessTederation October 20, 1952 KOlOV LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS AN INVESTMENT IN CHESS Po~;t;on No. 91 POI;l;"n No. 92 IFE MEMBERSHIP in the USCF is an investment in chess and an Euwe vs. Flohr STILL TOP FIELD L investment for chess. It indicates that its proud holder believes in C.1rIbad, 1932 After fOUl't~n rounds, the S0- chess ns a cause worthy of support, not merely in words but also in viet rcpresentatives still erowd to deeds. For while chess may be a poor man's game in the sense that it gether at the top in the Intel'l'onal does not need or require expensive equipment fm' playing or lavish event at Saltsjobaden. surroundings to add enjoyment to the game, yet the promotion of or· 1. Alexander Kot()v (Russia) .w._.w .... 12-1 ganized chess for the general development of the g'lmc ~ Iway s requires ~: ~ ~~~~(~tu(~~:I;,.i ar ·::::~ ::::::::::~ ~!~t funds. Tournaments cannot be staged without money, teams sent to international matches without funds, collegiate, scholastic and play· ;: t.~h!"'s~~;o il(\~::~~ ry i.. ··::::::::::::ij ); ~.~ ground chess encouraged without the adequate meuns of liupplying ad· 6. Gidcon S tahl ~rc: (Sweden) ...... 81-5l vice, instruction and encouragement. ~: ~,:ct.~.:~bG~~gO~~(t3Ji;Oi· · ·:::: ::::::7i~~ In the past these funds have largely been supplied through the J~: ~~j~hk Elrs'l;~san(A~~;t~~~ ) ::::6i1~ generosity of a few enthusiastic patrons of the game-but no game 11. -

A Package to Print Chessboards

chessboard: A package to print chessboards Ulrike Fischer November 1, 2020 Contents 1 Changes 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 Bugs and errors.....................................3 2.2 Requirements......................................4 2.3 Installation........................................4 2.4 Robustness: using \chessboard in moving arguments..............4 2.5 Setting the options...................................5 2.6 Saving optionlists....................................7 2.7 Naming the board....................................8 2.8 Naming areas of the board...............................8 2.9 FEN: Forsyth-Edwards Notation...........................9 2.10 The main parts of the board..............................9 3 Setting the contents of the board 10 3.1 The maximum number of fields........................... 10 1 3.2 Filling with the package skak ............................. 11 3.3 Clearing......................................... 12 3.4 Adding single pieces.................................. 12 3.5 Adding FEN-positions................................. 13 3.6 Saving positions..................................... 15 3.7 Getting the positions of pieces............................ 16 3.8 Using saved and stored games............................ 17 3.9 Restoring the running game.............................. 17 3.10 Changing the input language............................. 18 4 The look of the board 19 4.1 Units for lengths..................................... 19 4.2 Some words about box sizes.............................. 19 4.3 Margins......................................... -

Clues About Bluffing in Clue: Is Conventional Wisdom Wise?

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Electrical Department of Electrical Engineering and Engineering and Computer Science Computer Science 2019 Clues About Bluffing in Clue: Is Conventional Wisdom Wise? David Hansen Kyle D. Hansen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eecs_fac Part of the Engineering Commons Clues About Bluffing in Clue : Is Conventional Wisdom Wise? David M. Hansen Affiliate Member, IEEE1, Kyle D. Hansen2 1College of Engineering, George Fox University, Newberg, OR, USA 2Westmont College, Santa Barabara, CA, USA We have used the board game Clue as a pedagogical tool in our course on Artificial Intelligence to teach formal logic through the development of logic-based computational game-playing agents. The development of game-playing agents allows us to experimentally test many game-play strategies and we have encountered some surprising results that refine “conventional wisdom” for playing Clue. In this paper we consider the effect of the oft-used strategy wherein a player uses their own cards when making suggestions (i.e., “bluffing”) early in the game to mislead other players or to focus on acquiring a particular kind of knowledge. We begin with an intuitive argument against this strategy together with a quantitative probabilistic analysis of this strategy’s cost to a player that both suggest “bluffing” should be detrimental to winning the game. We then present our counter-intuitive simulation results from playing computational agents that “bluff” against those that do not that show “bluffing” to be beneficial. We conclude with a nuanced assessment of the cost and benefit of “bluffing” in Clue that shows the strategy, when used correctly, to be beneficial and, when used incorrectly, to be detrimental. -

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Preface 6 Introduction 9 1 Glossary of Attacking and Strategic Terms 11 2 Double Attack 23 2.1: Double Attacks with Queens and Rooks 24 2.2: Bishop Forks 31 2.3: Knight Forks 34 2.4: The Í+Ì Connection 44 2.5: Pawn Forks 45 2.6: The Discovered Double Attack 46 2.7: Another Type of Double Attack 53 Exercises 55 Solutions 61 3 The Role of the Pawns 65 3.1: Pawn Promotion 65 3.2: The Far-Advanced Passed Pawn 71 3.3: Connected Passed Pawns 85 3.4: The Pawn-Wedge 89 3.5: Passive Sacrifices 91 3.6: The Kamikaze Pawn 92 Exercises 99 Solutions 103 4 Attacking the Castled Position 106 4.1: Weakness in the Castled Position 106 4.2: Rooks and Files 112 4.3: The Greek Gift 128 4.4: Other Bishop Sacrifices 133 4.5: Panic on the Long Diagonal 143 4.6: The Knight Sacrifice 150 4.7: The Exchange Sacrifice 162 4.8: The Queen Sacrifice 172 Exercises 176 Solutions 181 5 Drawing Combinations 186 5.1: Perpetual Check 186 5.2: Repetition of Position 194 5.3: Stalemate 197 5.4: Fortress and Blockade 202 5.5: Positional Draws 204 Exercises 207 Solutions 210 6 Combined Tactical Themes 213 6.1: Material, Endings, Zugzwang 214 6.2: One Sacrifice after Another 232 6.3: Extraordinary Combinations 242 6.4: A Diabolical Position 257 Exercises 260 Solutions 264 7 Opening Disasters 268 7.1: Open Games 268 7.2: Semi-Open Games 274 7.3: Closed Games 288 8 Tactical Examination 304 Test 1 306 Test 2 308 Test 3 310 Test 4 312 Test 5 314 Test 6 316 Hints 318 Solutions 320 Index of Names 331 Index of Openings 335 THE ROLE OF THE PAWNS 3 The Role of the Pawns Ever since the distant days of the 18th century 3.1: Pawn Promotion (let us call it the time of the French Revolution, or of François-André Danican Philidor) we have known that “pawns are the soul of chess”. -

History of the World Rulebook

TM RULES OF PLAY Introduction Components “With bronze as a mirror, one can correct one’s appearance; with history as a mirror, one can understand the rise and fall of a state; with good men as a mirror, one can distinguish right from wrong.” – Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty History of the World takes 3–6 players on an epic ride through humankind’s history. From the dawn of civilization to the twentieth century, you will witness humanity in all its majesty. Great minds work toward technological advances, ambitious leaders inspire their 1 Game Board 150 Armies citizens, and unpredictable calamities occur—all amid the rise and fall (6 colors, 25 of each) of empires. A game consists of five epochs of time, in which players command various empires at the height of their power. During your turn, you expand your empire across the globe, gaining points for your conquests. Forge many a prosperous empire and defeat your adversaries, for at the end of the game, only the player with the most 24 Capitols/Cities 20 Monuments (double-sided) points will have his or her immortal name etched into the annals of history! Catapult and Fort Assembly Note: The lighter-colored sides of the catapult should always face upward and outward. 14 Forts 1 Catapult Egyptians Ramesses II (1279–1213 BCE) WEAPONRY I EPOCH 4 1500–450 BCE NILE Sumerians 3 Tigris – Empty Quarter Egyptians 4 Nile Minoans 3 Crete – Mediterranean Sea Hittites 4 Anatolia During this turn, when you fight a battle, Assyrians 6 Pyramids: Build 1 monument for every Mesopotamia – Empty Quarter 1 resource icon (instead of every 2). -

53Rd WORLD CONGRESS of CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010

53rd WORLD CONGRESS OF CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010 53rd World Congress of Chess Composition 34th World Chess Solving Championship Crete, Greece, 16–23 October 2010 Congress Programme Sat 16.10 Sun 17.10 Mon 18.10 Tue 19.10 Wed 20.10 Thu 21.10 Fri 22.10 Sat 23.10 ICCU Open WCSC WCSC Excursion Registration Closing Morning Solving 1st day 2nd day and Free time Session 09.30 09.30 09.30 free time 09.30 ICCU ICCU ICCU ICCU Opening Sub- Prize Giving Afternoon Session Session Elections Session committees 14.00 15.00 15.00 17.00 Arrival 14.00 Departure Captains' meeting Open Quick Open 18.00 Solving Solving Closing Lectures Fairy Evening "Machine Show Banquet 20.30 Solving Quick Gun" 21.00 19.30 20.30 Composing 21.00 20.30 WCCC 2010 website: http://www.chessfed.gr/wccc2010 CONGRESS PARTICIPANTS Ilham Aliev Azerbaijan Stephen Rothwell Germany Araz Almammadov Azerbaijan Rainer Staudte Germany Ramil Javadov Azerbaijan Axel Steinbrink Germany Agshin Masimov Azerbaijan Boris Tummes Germany Lutfiyar Rustamov Azerbaijan Arno Zude Germany Aleksandr Bulavka Belarus Paul Bancroft Great Britain Liubou Sihnevich Belarus Fiona Crow Great Britain Mikalai Sihnevich Belarus Stewart Crow Great Britain Viktor Zaitsev Belarus David Friedgood Great Britain Eddy van Beers Belgium Isabel Hardie Great Britain Marcel van Herck Belgium Sally Lewis Great Britain Andy Ooms Belgium Tony Lewis Great Britain Luc Palmans Belgium Michael McDowell Great Britain Ward Stoffelen Belgium Colin McNab Great Britain Fadil Abdurahmanović Bosnia-Hercegovina Jonathan -

Шахматных Задач Chess Exercises Schachaufgaben

Всеволод Костров Vsevolod Kostrov Борис Белявский Boris Beliavsky 2000 Шахматных задач Chess exercises Schachaufgaben РЕШЕБНИК TACTICAL CHESS.. EXERCISES SCHACHUBUNGSBUCH Шахматные комбинации Chess combinations Kombinationen Часть 1-2 разряд Part 1700-2000 Elo 3 Teil 1-2 Klasse Русский шахматный дом/Russian Chess House Москва, 2013 В первых двух книжках этой серии мы вооружили вас мощными приёмами для успешного ведения шахматной борьбы. В вашем арсенале появились двойной удар, связка, завлечение и отвлечение. Новый «Решебник» обогатит вас более изысканным тактическим оружием. Не всегда до короля можно добраться, используя грубую силу. Попробуйте обхитрить партнёра с помощью плаща и кинжала. Маскируйтесь, как разведчик, и ведите себя, как опытный дипломат. Попробуйте найти слабое место в лагере противника и в нужный момент уничтожьте защиту и нанесите тонкий кинжальный удар. Кстати, чужие фигуры могут стать союзниками. Умелыми манёврами привлеките фигуры противника к их королю, пускай они его заблокируют так, чтобы ему, бедному, было не вздохнуть, и в этот момент нанесите решающий удар. Неприятно, когда все фигуры вашего противника взаимодействуют между собой. Может, стоить вбить клин в их порядки – перекрыть их прочной шахматной дверью. А так ли страшна атака противника на ваши укрепления? Стоит ли уходить в глухую оборону? Всегда ищите контрудар. Тонкий промежуточный укол изменит ход борьбы. Не сгрудились ли ваши фигуры на небольшом пространстве, не мешают ли они друг другу добраться до короля противника? Решите, кому всё же идти на штурм королевской крепости, и освободите пространство фигуре для атаки. Короля всегда надо защищать в первую очередь. Используйте это обстоятельство и совершите открытое нападение на него и другие фигуры. И тогда жернова вашей «мельницы» перемелют всё вражеское войско. -

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712 Congratulations on your purchase of Excalibur Electronics’ IVAN! You’ve purchased both your own personal chess trainer and a partner who’s always ready for a game—and who can improve as you do! Talking and audio sounds add anoth- Play a Game Right Away er dimension to your IVAN computer for After you have installed the batteries, the increased enjoyment and play value. display will show the chess board with all the pieces on their starting squares. Place Find the Pieces the plastic chess pieces on their start Turn Ivan over carefully with his chess- squares using the LCD screen as a guide. board facedown. Find the door marked The dot-matrix display will show “PIECE COMPARTMENT DOOR”. 01CHESS. This indicates you are at the Open it and remove the chess pieces. first move of the game and ready to play Replace the door and set the pieces aside chess. for now. Unless you instruct it otherwise, IVAN gives you the White pieces—the ones at Install the Batteries the bottom of the board. White always With Ivan facedown, find the door moves first. You’re ready to play! marked “BATTERY DOOR’. Open it and insert four (4) fresh, alkaline AA batteries Making your move in the battery holder. Note the arrange- Besides deciding on a good move, you ment of the batteries called for by the dia- have to move the piece in a way that Ivan gram in the holder. Make sure that the will recognize what's been played. Think positive tip of each battery matches up of communicating your move as a two- with the + sign in the battery compart- step process--registering the FROM ment so that polarity will be correct. -

French Revolution Board Game

Name ____________________________ Block ___________ French Revolution Board Game With so much happening and so many twists and turns, it is hard not to compare the French Revolution to an awesome history-based board game. Luckily, you get the opportunity to make one! Your task is to create a board game that is fun to play, and teaches players about the French Revolution (even if they don’t know they are learning). Your game should cover the events from the meeting of the Three Estates in 1789 to the Congress of Vienna in 1815. You may make up an entirely new game or start with an existing game and modify the set up. Some possibilities: • Change a Monopoly board so that the properties and pieces fit the French Revolution and not beachfront gambling towns. • Revisit the game of Life with revolutionary tracks rather than career choices. • Trivia-based game where number of moves is based on answering questions. • Revise Chutes and Ladders to reflect the changes in France during the Revolution. Rubric DOES NOT MEET CRITERIA EXCELLENT ADEQUATE SCORE EXPECTATIONS Relates clearly to each Misses some phases or Game does not relate to Information phase of the French key people and events, the French Revolution ___/25 Revolution with but uses some French except in name only. accurate information. Revolution ideas. Includes all parts* and Instructions are unclear Not a playable game. Playability is ready to be played. or not included. Missing necessary pieces or not ___/25 enough cards for full game. Creatively modifies all Basic structure of the Simply makes name Attention to elements of gameplay original game is the changes to an existing Detail and set up for a same, with some game or makes few ___/25 complete French relevant modifications efforts to creatively Revolution experience.