Steps Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code of Federal Regulations GPO Access

10±20±97 Monday Vol. 62 No. 202 October 20, 1997 Pages 54339±54568 Briefings on how to use the Federal Register For information on briefings in Washington, DC, see the announcement on the inside cover of this issue. Now Available Online Code of Federal Regulations via GPO Access (Selected Volumes) Free, easy, online access to selected Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) volumes is now available via GPO Access, a service of the United States Government Printing Office (GPO). CFR titles will be added to GPO Access incrementally throughout calendar years 1996 and 1997 until a complete set is available. GPO is taking steps so that the online and printed versions of the CFR will be released concurrently. The CFR and Federal Register on GPO Access, are the official online editions authorized by the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register. New titles and/or volumes will be added to this online service as they become available. http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr For additional information on GPO Access products, services and access methods, see page II or contact the GPO Access User Support Team via: ★ Phone: toll-free: 1-888-293-6498 ★ Email: [email protected] federal register 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 202 / Monday, October 20, 1997 SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES PUBLIC Subscriptions: Paper or fiche 202±512±1800 Assistance with public subscriptions 512±1806 General online information 202±512±1530; 1±888±293±6498 FEDERAL REGISTER Published daily, Monday through Friday, (not published on Saturdays, Sundays, or on official holidays), Single copies/back copies: by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Paper or fiche 512±1800 Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Assistance with public single copies 512±1803 Register Act (49 Stat. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Law School Announcements 2013-2014 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications Fall 2013 Law School Announcements 2013-2014 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 2013-2014" (2013). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 2. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago The Law School Announcements Fall 2013 ii The Law School Contents OFFICERS AND FACULTY ........................................................................................................ 1 Officers of Administration ............................................................................................ 1 Officers of Instruction .................................................................................................... 1 Law School Visiting Committee................................................................................... 7 THE LAW SCHOOL .............................................................................................................. -

IIS Windows Server

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly FALL 1995 NEVADA HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY EDITORIAL BOARD Eugene Moehring, Chairman, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Marie Boutte, University of Nevada, Reno Robert Davenpo'rt, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Doris Dwyer, Western Nevada Community College Jerome E. Edwards, University of Nevada, Reno Candace C. Kant, Community College of Southern Nevada Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Library and Archives Willard H. Rollings, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Hal K. Rothman, University of Nevada, Las Vegas The Nevada Historical Society Quarterly solicits contributions of scholarly or popular interest dealing with the following subjects: the general (e.g., the political, social, economic, constitutional) or the natural history of Nevada and the Great Basin; the literature, languages, anthropology, and archaeology of these areas; reprints of historic documents; reviews and essays concerning the historical literature of Nevada, the Great Basin, and the West. Prospective authors should send their work to The Editor, Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, 1650 N. Virginia St., Reno, Nevada 89503. Papers should be typed double-spaced and sent in duplicate. All manuscripts, whether articles, edited documents, or essays, should conform to the most recent edition of the University of Chicago Press Manual of Style. Footnotes should be typed double-spaced on separate pages and numbered consecutively. Correspondence concerning articles and essays is welcomed, and should be addressed to The Editor. © Copyright Nevada Historical Society, 1995. The Nevada Historical Society Quarterly (ISSN 0047-9462) is published quarterly by the Nevada Historical Society. The Quarterly is sent to all members of the Society. Membership dues are: Student, $15; Senior Citizen without Quan !rly, $15; Regular, $25; Family, $35; Sustaining, $50; Contributing, $100; Departmental Fellow, $250; Patron, $500; Benefactor, $1,000. -

Gangs and Organized Crime Groups

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE JOURNAL OF FEDERAL LAW AND PRACTICE Volume 68 November 2020 Number 5 Acting Director Corey F. Ellis Editor-in-Chief Christian A. Fisanick Managing Editor E. Addison Gantt Associate Editors Gurbani Saini Philip Schneider Law Clerks Joshua Garlick Mary Harriet Moore United States The Department of Justice Journal of Department of Justice Federal Law and Practice is published by Executive Office for the Executive Office for United States United States Attorneys Attorneys Washington, DC 20530 Office of Legal Education Contributors’ opinions and 1620 Pendleton Street statements should not be Columbia, SC 29201 considered an endorsement by Cite as: EOUSA for any policy, 68 DOJ J. FED. L. & PRAC., no. 5, 2020. program, or service. Internet Address: The Department of Justice Journal https://www.justice.gov/usao/resources/ of Federal Law and Practice is journal-of-federal-law-and-practice published pursuant to 28 C.F.R. § 0.22(b). Page Intentionally Left Blank Gangs & Organized Crime In This Issue Introduction....................................................................................... 1 David Jaffe Are You Maximizing Ledgers and Other Business Records in Drug and Organized Crime Investigations? ............. 3 Melissa Corradetti Jail and Prison Communications in Gang Investigations ......... 9 Scott Hull Federally Prosecuting Juvenile Gang Members........................ 15 David Jaffe & Darcie McElwee Scams-R-Us Prosecuting West African Fraud: Challenges and Solutions ................................................................................... 31 Annette Williams, Conor Mulroe, & Peter Roman Gathering Gang Evidence Overseas ............................................ 47 Christopher J. Smith, Anthony Aminoff, & Kelly Pearson Exploiting Social Media in Gang Cases ....................................... 67 Mysti Degani A Guide to Using Cooperators in Criminal Cases...................... 81 Katy Risinger & Tim Storino Novel Legal Issues in Gang Prosecutions .................................. -

Expert Testimony on Organized Crime Under the Federal Rules of Evidence: United States V

Hofstra Law Review Volume 22 | Issue 1 Article 5 1993 Expert Testimony on Organized Crime Under the Federal Rules of Evidence: United States v. Frank Locascio and John Gotti Jason Sabot Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sabot, Jason (1993) "Expert Testimony on Organized Crime Under the Federal Rules of Evidence: United States v. Frank Locascio and John Gotti," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 22: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol22/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sabot: Expert Testimony on Organized Crime Under the Federal Rules of Ev COMMENT EXPERT TESTIMONY ON ORGANIZED CRIME UNDER THE FEDERAL RULES OF EVIDENCE: UNITED STATES V. FRANK LOCASCIO AND JOHN GOTTI CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................. 178 H. EXPERT TESTIMONY AT COMMON LAW ............. 182 III. THE FEDERAL RULES OF EVIDENCE ................ 185 A. Rule 702 ............................. 186 B. Rule 703 ............................. 187 IV. HELPFULNESS OF THE GOVERNMENT'S USE OF "ExPERTs" ON ORGANIZED CRIME ................ 189 A. General Background of the Gotti Case .......... 193 B. Gotti and the Scope of Expert Testimony ......... 194 1. United States v. Daly .................. 197 2. United States v. Long .................. 200 C. Qualifications of an Expert on Organized Crime ........................ 204 V. THE "REASONABLE RELIANCE" REQUIREMENT OF RULE 703 ................................. 205 A. The Gotti Flexible Approach ................ -

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations

Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations Updated July 28, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41576 SUMMARY R41576 Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking July 28, 2020 Organizations June S. Beittel Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) pose the greatest crime threat to the United States Analyst in Latin American and have “the greatest drug trafficking influence,” according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Affairs Administration’s (DEA’s) annual National Drug Threat Assessment. These organizations, often referred to as transnational criminal organizations (TCOs), continue to diversify into crimes of extortion, human smuggling, and oil theft, among others. Their supply chains traverse the Western Hemisphere and the globe. Their extensive violence since 2006 has caused Mexico’s homicide rate to spike. They produce and traffic illicit drugs into the United States, including heroin, methamphetamine, marijuana, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and they traffic South American cocaine. Mexican DTO activities significantly affect the security of both the United States and Mexico. As Mexico’s DTOs expanded their control of the opioids market, U.S. overdoses rose sharply according to the Centers for Disease Control, setting a record in 2019 with more than 70% of overdose deaths involving opioids, including fentanyl. Many analysts believe that Mexican DTOs’ role in the trafficking and producing of opioids is continuing to expand. Evolution of Mexico’s Criminal Environment Mexico’s DTOs have been in constant flux, and yet they continue to wield extensive political and criminal power. In 2006, four DTOs were dominant: the Tijuana/Arellano Félix Organization (AFO), the Sinaloa Cartel, the Juárez/Vicente Carillo Fuentes Organization (CFO), and the Gulf Cartel. -

Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs Usa Overview

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. " OUTLAW MOTORCYCLE GANGS USA OVERVIEW 147691 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in , 'is document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by Ca11fornia Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. State of California Department of Justice Bureau of Organized Crime and Criminal Intelligence '. 1r+'7~91 ,":', NATIONAL YOUTH GANG INFORMATION CENTER 4301 North Fairfax Drive, Suite 730 Arlington, Virginia 22203 1-800-446-GANG • 703-522-4007 NYGIC Document Number: Permission Codes: OUTLAW MOTORCYCLE GANGS USA OVERVIEW This report is designed to give a brief overview of the organized crime activities of outlaw motorcycle gangs in the United States. The information contained in the report is for the restricted use of law enforcement personnel only. This information was originally presented at the 36th Annual National LEIU Training Seminar in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in May 1991. Prepared By " The State of California Department of Justice Bureau of Organized Crime and Criminal Intelligence Ann Richardson, Criminal Intelligence Specialist OUTLAW MOTORCYCLE GANGS - USA OVERVIEW OUTLINE ;, I. Evolution '. II. Big Five Update A. Hells Angels B. Pagans C. Outlaws D. Bandidos E. Sons of Silence III. -

Fiscal Year 1994

1Li i1 Aomy9 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS STATISTICAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 1994 iIAo$eaEITuR The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ord mary party to controver3y but of sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all and whose interest therefore in criminal prosecution is not that it shall win case but that justice shall be done As such he is in peculiar and very definite sense the sePvant of the law the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor -- indeed he should do so But while he may strike hard blows he is not at liberty to strike foul ones It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods it is calculated to produce wrongful conviction as to about use every legitimate means to bring just one Quoted from the Statement of Mr Justice Sutherland in Berger United States 295 U.S 88 1935 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS OFFICES PERSONNEL ATTORNEYS OFFICES II CRIMINAL PROSECUTIONS BY ThE UNITED STATES 10 District of Columbia Superior Court Proceedings 15 PRIORITY CRIMINAL PROSECUTION AREAS 15 Violent Crime 16 Firearms Prosecutions 17 Violent Street Gangs 18 Violent Indian Crime 18 Narcotics Prosecutions 20 Organized Crime 21 White Collar Crime 21 Financial Institution Fraud 22 Official Corruption 23 Espionage 24 Health Care Fraud 25 Environmental Crime 26 Computer Crime 27 Other White Collar Crime 27 Civil Rights Prosecutions FORFEITURE LITIGATION 29 111 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS -

Pennsylvania .Crime

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. • · Pennsylvania • .Crime. ·Commis'sion • .~ ."• 1989REPORT • • COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA • • • PENNSYLVANIA CRIME COMMISSION • 1989REPORT • 138666 • U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated In this document a~e those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the Nalionallnslitute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been • granted by ~ennsy1vania Crime Commission to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further repr~duction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission • of the copynght owner. • Printed in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania 1100 E. Hector Street Conshohocken, PA 19428 • (215) 834-1164 • PENNSYLVANIA CRIME • COMMISSION Michael}. Reilly, Esq. - Chairman Charles H. Rogovin, Esq. - Vice-Chairman • Trevor Edwards, Esq. - Commissioner James H. Manning, Jr., Esq. - Commissioner Arthur L. Coccodrilli - Commissioner* EXECUTIVE STAFF Frederick T. Martens - Executive Director G. Alan Bailey - Deputy Executive Director/Chief Counsel • Willie C. Byrd - Director of Investigations Gerald D. Rockey - SAC, Intelligence STAFF PERSONNEL Sharon L. Beerman Gino L. Lazzari Nancy B. Checket Geraldine Lyons - Student Intern • Daniel A. Chizever Doris R. Mallin Ross E. Cogan Joseph A. Martinez Thomas J. Connor Margaret A. Millhouse Terri Cram bo Russell J. Millhouse Christopher J. DeCree Edward J. Mokos Michael B. DiPietro MarkA. Morina • Joseph P. Dougherty Gertrude F. Payne William F. Foran Wasyl Polischuk J. R. Freeman Willie M. Powell Edgar Gaskin Edward M. Recke Perrise Hatcher Lois Ryals Barbara A. -

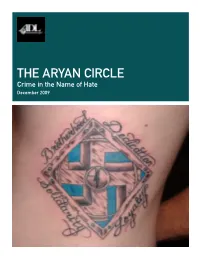

THE ARYAN CIRCLE: CRIME in the NAME of HATE Executive Summary

THE ARYAN CIRCLE Crime in the Name of Hate December 2009 THE ARYAN CIRCLE : Crime in the Name of Hate Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction: Officers Killed in Bastrop 2 The Aryan Circle and Racist Prison Gangs 3 Origins 4 Size and Membership 5 Organization 6 Control and Power Issues 7 Recruitment and Prospecting 8 Demographics 9 The Role of Women in the Aryan Circle 10 From the Prisons to the Streets 11 Ideology and Group Solidarity 12 Relationships with Other Groups 13 Drug Use and the Aryan Circle 14 Aryan Circle Criminal Activity a. Organized Crime: Profit b. Organized Crime: Other Violence c. Hate Crimes Appendix: Aryan Circle Identifiers & Tattoos THE ARYAN CIRCLE: CRIME IN THE NAME OF HATE Executive Summary The Aryan Circle is a large, growing and dangerous white supremacist gang based primarily in Texas. Active in prisons and on the streets, it has a long track record of murder, including the deaths of two police officers in Bastrop, Louisiana, in 2007. • The Aryan Circle originated in the Texas prison system in the mid-1980s and is now the second largest white supremacist gang in Texas. • The Aryan Circle has four segments: its Texas prison population, its federal prison population, its out-of-state prison population, and its non-incarcerated population. Total membership is probably over 1,400, making it one of the largest white supremacist groups in the United States. The most disturbing trend is the growth in its free-world membership. • The Aryan Circle is headed by an elected president and run by senior members. -

Immigrant in America Reel Listing 1

Immigrant in America Reel Listing Aagardd, G. (Gustav), 1852. Belsheim, G. G. Staerke haender. Secret Societies. Minneapolis, Folkebladet. 1900 Mason City, Iowa, [Trinity Lutheran Church]. 1910 Reel: 1, No. 1 Reel: 2, No. 12 Ager, Waldemar, 1869-1941. Beretning om det 18de ordentlige synodemøde. Gamlelandets sønner: fjerde tusen. Decorah, Iowa, Den Norske Synodes Forlag. 1904 Oslo, H. Aschehoug & Co. 1926 Reel: 2, No. 13 Reel: 1, No. 2 Bergh, J. A. (Johan Arndt), 1847. Ager, Waldemar, 1869-1941. Den norsk lutherske kirkes historie i Amerika. I Strømmen. Minneapolis, Minn., the author. 1914 Eau Claire, Wis., Fremad Publishing Co. 1908 printed by Augsburg Publishing House. illustreret af B. Blessum. 2. udg. Reel: 2, No. 14 Reel: 1, No. 3 Bergsland, H. H. Ager, Waldemar, 1869-1941. Gjensvar til pastor Melands "redegjørelse" osv. Kristus for pilatus: en norsk-amerikansk Minnesota, Hauges Synodes Trykkeri. 1895 Fortaelling. Reel: 2, No. 15 Eau Claire, Wis., Fremad Publ. Co. 1910 Reel: 1, No. 4 Biørn, L. M. (Ludvig Marinus), 1835-1908. Pastor P. A. Rasmussen. Alterbog: til brug ved den offentlige Gudstjeneste og Minneapolis, Augsburg Publishing House Trykkeri. de Kirkelige handlinger for Synoden for den 1905 norskev.-luth. kirke i Amerika. Reel: 2, No. 16 Decorah, Iowa, Lutheran Publishing House. 1901 Reel: 1, No. 5 Birkeland, Knut B. (Knut Bergesen), 1857-1925. Brydninger i den Forenede Kirke. Anderson, R. (Rasmus), 1848-1930. Minneapolis, C. Rasmussen's Bogtrykkeri. 1892 Pastor Claus Laurits Clausen. Reel: 2, No. 17 New York, Faas hos Forfatteren, vor Frelsers Danske ev. luth. Kirke. Birkeland, Knut B. (Knut Bergesen), 1857-1925. Kirkehistorisk Bidrag ved R.