Maids in Akihabara : Fantasy, Consumption and Role-Playing in Tokyo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nankai Electric Railway Company Profile 2020 Corporate Philosophy

Nankai Electric Railway Company Profile 2020 Corporate Philosophy Based on our Corporate Philosophy, which we have adapted to the latest social trends, and the message of our corporate symbol, the Company considers itself a comprehensive lifestyle provider centered on railway operations. As such, we aim to help build prosperity and contribute to society through broad-based businesses that support every aspect of people’s lifestyles. Corporate Philosophy (Drawn up April 1, 1993) With expertise and dynamism, forging the way to the future ◆ Contribution to the Community Justifying public trust as an all-round lifestyle provider and building a better society ◆ Putting the Customer First Providing excellent services for the customer and bringing living comfort and cultural enrichment ◆ Future Challenges Meeting the needs of coming generations with bold energy and creativity ◆ A Dynamic Workplace Creating a workplace brimming with vitality and harnessing the expertise and personal strengths of every employee Corporate Symbol Our logo symbolizes our striving for the future as a comprehensive lifestyle company. It features two wings, one vivid red and one bright orange. The red, like the sun shining on the southern seas, represents our passion, and the orange the optimism of the human heart. Message from the Management 2 Retail 11 Business Area 3 Leisure and Services 12 Construction and Other 12 Route Map 4 Segment Information 5 Key Themes of the Nankai Group 13 Contents Transportation 7 Management Vision 2027 Real Estate 9 Corporate Information 15 1 Nankai Electric Railway Company Profile 2020 Message from the Management President and CEO Achikita Teruhiko Founded in 1885, Nankai Electric Railway Co., Ltd. -

A 5 Day Tokyo Itinerary

What To Do In Tokyo - A 5 Day Tokyo Itinerary by NERD NOMADS NerdNomads.com Tokyo has been on our bucket list for many years, and when we nally booked tickets to Japan we planned to stay ve days in Tokyo thinking this would be more than enough. But we fell head over heels in love with this metropolitan city, and ended up spending weeks exploring this strange and fascinating place! Tokyo has it all – all sorts of excellent and corky museums, grand temples, atmospheric shrines and lovely zen gardens. It is a city lled with Japanese history, but also modern, futuristic neo sci- streetscapes that make you feel like you’re a part of the Blade Runner movie. Tokyo’s 38 million inhabitants are equally proud of its ancient history and culture, as they are of its ultra-modern technology and architecture. Tokyo has a neighborhood for everyone, and it sure has something for you. Here we have put together a ve-day Tokyo itinerary with all the best things to do in Tokyo. If you don’t have ve days, then feel free to cherry pick your favorite days and things to see and do, and create your own two or three day Tokyo itinerary. Here is our five day Tokyo Itinerary! We hope you like it! Maria & Espen Nerdnomads.com Day 1 – Meiji-jingu Shrine, shopping and Japanese pop culture Areas: Harajuku – Omotesando – Shibuya The public train, subway, and metro systems in Tokyo are superb! They take you all over Tokyo in a blink, with a net of connected stations all over the city. -

Sunshine City Prince Hotel

November 2018 Sunshine City Prince Hotel Announcing the birth of a hotel floor for all fans of Japan’s subculture, including those from other countries, in Tokyo’s Ikebukuro district! Opening of a concept floor in April 2019 (tentative) In April 2019 (tentative), Sunshine City Prince Hotel (3-1-5 Higashi-Ikebukuro, Toshima-ku, Tokyo; Tsuyoshi Okumura, General Manager) will open a new floor taking Japanese subculture as its theme. This concept floor will be designed to motivate trips to Japan by overseas fans of Japanese anime, manga, and other elements of Japanese subculture, and make their stay at the hotel even more fun. Located on the 25th floor of the hotel, the concept floor will consist of four common-use areas and 20 concept rooms , and have features differing from hotel floors having only rooms for guests. Taking “a dream-come-true experience of a stay surrounded by things you love” as its watchword, this floor will be designed especially for guests from other countries who love anime, manga, and other elements of Japanese subculture. It will make their stay a dream-like one unlike anything they have experienced before. Instead of having the same contents throughout the year, the floor will change the tie-up contents in step with the going needs and with the right timing, for use by a wider circle of fans. Common-use area: event space Common-use area: library space Twin room A (conceptual depi ction) (conceptual depiction) (conceptual depiction) Together with the Shinjuku and Shibuya districts, the Ikebukuro district of Tokyo’s Toshima Ward, in which our hotel is situated, is one of the three major subcenters of Tokyo. -

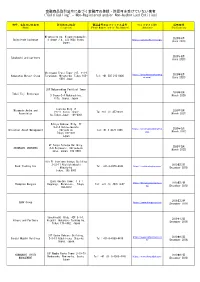

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) Miyakojima-ku, Higashinodamachi, 2020年6月 SwissTrade Exchange 4-chōme−7−4, 534-0024 Osaka, https://swisstrade.exchange/ (June 2020) Japan 2020年6月 Takahashi and partners (June 2020) Shiroyama Trust Tower 21F, 4-3-1 https://www.hamamatsumerg 2020年6月 Hamamatsu Merger Group Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105- Tel: +81 505 213 0406 er.com/ (June 2020) 0001 Japan 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. -

TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP JR Yamanote

JR Yamanote Hibiya line TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP Ginza line Chiyoda line © Tokyo Pocket Guide Tozai line JR Takasaka Kana JR Saikyo Line Koma line Marunouchi line mecho Otsuka Sugamo gome Hanzomon line Tabata Namboku line Ikebukuro Yurakucho line Shin- Hon- Mita Line line A Otsuka Koma Nishi-Nippori Oedo line Meijiro Sengoku gome Higashi Shinjuku line Takada Zoshigaya Ikebukuro Fukutoshin line nobaba Todai Hakusan Mae JR Joban Asakusa Nippori Line Waseda Sendagi Gokokuji Nishi Myogadani Iriya Tawara Shin Waseda Nezu machi Okubo Uguisu Seibu Kagurazaka dani Inaricho JR Shinjuku Edo- Hongo Chuo gawa San- Ueno bashi Kasuga chome Naka- Line Higashi Wakamatsu Okachimachi Shinjuku Kawada Ushigome Yushima Yanagicho Korakuen Shin-Okachi Ushigome machi Kagurazaka B Shinjuku Shinjuku Ueno Hirokoji Okachimachi San-chome Akebono- Keio bashi Line Iidabashi Suehirocho Suido- Shin Gyoen- Ocha Odakyu mae Bashi Ocha nomizu JR Line Yotsuya Ichigaya no AkihabaraSobu Sanchome mizu Line Sendagaya Kodemmacho Yoyogi Yotsuya Kojimachi Kudanshita Shinano- Ogawa machi Ogawa Kanda Hanzomon Jinbucho machi Kokuritsu Ningyo Kita Awajicho -cho Sando Kyogijo Naga Takebashi tacho Mitsu koshi Harajuku Mae Aoyama Imperial Otemachi C Meiji- Itchome Kokkai Jingumae Akasaka Gijido Palace Nihonbashi mae Inoka- Mitsuke Sakura Kaya Niju- bacho shira Gaien damon bashi bacho Tameike mae Tokyo Line mae Sanno Akasaka Kasumi Shibuya Hibiya gaseki Kyobashi Roppongi Yurakucho Omotesando Nogizaka Ichome Daikan Toranomon Takaracho yama Uchi- saiwai- Hachi Ebisu Hiroo Roppongi Kamiyacho -

MANGA⇔TOKYO (Venue: La Villette, Paris, France)

2018.7.5 Press Release: Opening Announcement The National Art Center, Tokyo The Japan Foundation November 29 (Thu.) – December 30 (Sun.), 2018 The National Art Center, Tokyo International Exhibition | Japonismes2018 official program MANGA⇔TOKYO (Venue: La Villette, Paris, France) Illustration by Yoh Yoshinari / Graphic design by Tsuyoshi Kusano ©Crypton Future Media, INC. www.piapro.net / ©khara / ©Naoko Takeuchi/PNP, Toei Animation / ©Osamu Akimoto, Atelier Beedama/SHUEISHA / ©SOTSU, SUNRISE / ©TOHO CO., LTD. The National Art Center, Tokyo and the Japan Foundation are pleased to announce that the "MANGA ⇔ TOKYO" exhibition will be held at La Villette in Paris, France from November 29, 2018 (Thursday). Japan's manga, animation, games, SFX films (tokusatsu) are reflective of the social change and technological development of the city of <Tokyo>. This exhibition pursues to represent these depictions through numerous drawings, models and images. How did the characteristics of the real city inspire the direction of fiction? How did these fictions and their characters present us with a new hybrid reality, now multilayered to the real city? This exhibition does focus on Japanese manga, animation, games, and SFX films (tokusatsu), but through them it also portrays the city of <Tokyo>, already iconic in a lot of people’s mind. It hopes to delve into the meaning and possibilities for Japan’s animation, manga and its gaming culture, as they have become tourism drawcards and created what for many enthusiasts is a "sacred pilgrimage" when visiting Japan. The “MANGA⇔TOKYO” exhibition follows the first highly successful “Manga*Anime*Games from Japan” exhibition held at the National Art Center, Tokyo in 2015, and is one of the official programs of “Japonismes 2018: les âmes en résonance”, an extensive cultural season to showcase the unrevealed beauty of Japanese culture in France. -

GETTING READY for TAKE-OFF How Generation Z Is Starting to Shape Corporate Travel of the Future

connectCWT’s business travel magazine | UK & Ireland | Spring 2019 GETTING READY FOR TAKE-OFF How Generation Z is starting to shape corporate travel of the future Osaka An economic and cultural powerhouse The state of the hotel market The effect of technology and mergers Health & travel Keeping fit & healthy when travelling connect 1/2019 – Editorial 3 Welcome to Connect magazine for spring 2019! egular readers will notice that I’m not the person you usually see when flipping open your issue of Connect. From this magazine onwards, we will be rotating the slot and featuring guest editors Rfrom across CWT. I’m privileged to be the first one of many to take this coveted position. As SVP and Chief Experience Officer at RoomIt by CWT my role is to ensure we match travellers with the right room at the right rate, while helping companies control their budgets and improve travel oversight. We touch on this in our feature on recent developments in the hotel market (page 18). In the same article, we show how innovative travel managers can achieve savings beyond negotiated rates at the same time as still maintaining compliance in travel programmes. In this issue we also compare the much-talked and -written about Millennials with their younger counterparts, Generation Z (page 8). We discover how they might shape the corporate travel of the future and what they expect in a travel programme, from hotel stays to long-haul flights. With destinations in mind, we head east to Japan and the city of Osaka (page 12), an exciting metropolis that works as hard as it plays. -

Off-Track Betting on Your Doorstep *Charges for Pay-Seats, Etc., Are Valid As of Nov

Ashiyu foot bath at WINS Isawa Excel Floor of WINS Shin-Yokohama Carousel at WINS Shin-Shirakawa WINS Kyoto Entrance to WINS Namba WINS Sasebo in Huis ten Bosch WINS – off-track betting on your doorstep *Charges for pay-seats, etc., are valid as of Nov. 13th, 2009. Did you know that you can place a bet without going to a racecourse? Just pop in to your local WINS off-track betting facility! With branches all over Japan, WINS are also convenient places for meeting spot or just taking a coffee break. Some WINS facilities are set up with comfortable sofas and PC and monitor for your personal use, allowing you to enjoy the whole day at the races! Of course, WINS also make payouts on winning bets. WINS Sapporo(some pay-seats) WINS Shizunai WINS Kushiro WINS Ginza-dori WINS Korakuen (some pay-seats) WINS Kinshicho (some pay-seats) Dodo-Biratori Shizunai Route JR Senmo Main Line Main Senmo JR ▲Sapporo Stn. Homac ▼ 391 Subway Ryogoku Ichikawa ▼ Hokkaido Sales WINS Posful Fujiya Toei Subway Hibiya Line Ginza Stn. Police box Kasuga Stn. Kinshicho Stn. WINS Sapporo Toho Subway Line Shizunai Kushiro Loop Road Setsuribashi Oedo Line JR Sobu Line Cosmo● Shizunai River Kushiro Timber Building B Higashi Ginza Mitsukoshi ● ● ● Subway Fire Station Reservoir ● Korakuen Stn. JR Yurakucho Stn. Hanzomon Line Stn. Dept. Store Expressway ● Suidobashi Stn. Plaza ▲ Miyuki-dori 44 Arche● ●Senshu-An Seiko Mart ● Shizunai Kushiro Rosai● Kushiro Ginza Stn. Tokyo Dome City Shopping Kinshicho Stn. Ginza-dori Kamotsu Showa-dori Attractions T street Police Hospital Yotsume-dori Municipal Nemuro o Marunouchi Line Subway e ● Jidosha Matsuya Dept. -

Grand Opening of Q Plaza IKEBUKURO July 19 (Fri), 10.30 Am Ikebukuro’S Newest Landmark

July 17, 2019 Tokyu Land Corporation Tokyu Land SC Management Corporation Grand Opening of Q Plaza IKEBUKURO July 19 (Fri), 10.30 am Ikebukuro’s Newest Landmark Tokyu Land Corporation (Head office: Minato-ku, Tokyo; President: Yuji Okuma; hereafter “Tokyu Land”) and Tokyu Land SC Management Corporation (Head office: Minato-ku, Tokyo; President: Toshihiro Awatsuji) will open Q Plaza IKEBUKURO at 10.30 am on July 19 (Fri) as Ikeburo’s newest landmark, based on Toshima Ward’s International City of Arts & Culture Toshima vision. As a new entertainment complex where people of all ages can have fun, enjoying different experiences all day long on its 16 stores, including a cinema complex, an arcade and amusement center, and retail and dining options, Q Plaza IKEBUKUO will create more bustle in the Ikebukuro area, which is currently being redeveloped, and will bring life to the district in partnership with the local community. ■Many products exclusive to Q Plaza IKEBUKURO and limited time services to commemorate opening Opening for the first time in the area as flagship store, the AWESOME STORE & CAFÉ will offer a lineup of products exclusive to the Ikebukuro store, including AWESOME FLY! PO!!! with three flavors to choose from and a tuna egg bacon omelette bagel. In commemoration of the opening, Schmatz Beer Dining will offer sausages developed by Takeshi Murakami, a sausage researcher with a workshop in Yamanashi, for a limited time only. It will also provide customers with one free beer and a 19% discount for table-only reservations to commemorate the opening of its 19th store. -

Tokyo Orientation 2017 Ajet

AJET News & Events, Arts & Culture, Lifestyle, Community TOKYO ORIENTATION 2017 Stay Cool and Look Clean - how to be fashionably sweaty Find the Fun - how to get involved with SIGs (and what they exactly are) Studying Japanese - how to ganbaru the benkyou on your sumaho Shinju-who? - how to have fun and understand Shinjuku Hot and Tired in Tokyo - how to spend those orientation evenings The Japanese Lifestyle & Culture Magazine Written by the International Community in Japan1 CREDITS & CONTENT HEAD EDITOR HEAD OF DESIGN & HEAD WEB EDITOR Lilian Diep LAYOUT Nadya Dee-Anne Forbes Ashley Hirasuna ASSITANT HEAD EDITOR ASSITANT WEB EDITOR Lauren Hill COVER PHOTO Amy Brown Shantel Dickerson SECTION EDITORS SOCIAL MEDIA Kirsty Broderick TABLE OF CONTENTS John Wilson Jack Richardson Michelle Cerami Shantel Dickerson PHOTO Hayley Closter Shantel Dickerson Nicole Antkiewicz COPY EDITORS Verushka Aucamp Jasmin Hayward ART & PHOTOGRAPHY Tresha Barrett Tresha Barrett Hannah Varacalli Bailey Jo Josie Jasmin Hayward Abby Ryder-Huth Hannah Martin Sabrina Zirakzadeh Shantel Dickerson Jocelyn Russell Illaura Rossiter Micah Briguera Ashley Hirasuna This magazine contains original photos used with permission, as well as free-use images. All included photos are property of the author unless otherwise specified. If you are the owner of an image featured in this publication believed to be used without permission, please contact the Head of Graphic Design and Layout, Ashley Hirasuna, at ashley. [email protected]. This edition, and all past editions of AJET CONNECT, -

Tokyo Sightseeing Route

Mitsubishi UUenoeno ZZoooo Naationaltional Muuseumseum ooff B1B1 R1R1 Marunouchiarunouchi Bldg. Weesternstern Arrtt Mitsubishiitsubishi Buildinguilding B1B1 R1R1 Marunouchi Assakusaakusa Bldg. Gyoko St. Gyoko R4R4 Haanakawadonakawado Tokyo station, a 6-minute walk from the bus Weekends and holidays only Sky Hop Bus stop, is a terminal station with a rich history KITTE of more than 100 years. The “Marunouchi R2R2 Uenoeno Stationtation Seenso-jinso-ji Ekisha” has been designated an Important ● Marunouchi South Exit Cultural Property, and was restored to its UenoUeno Sta.Sta. JR Tokyo Sta. Tokyo Sightseeing original grandeur in 2012. Kaaminarimonminarimon NakamiseSt. AASAHISAHI BBEEREER R3R3 TTOKYOOKYO SSKYTREEKYTREE Sttationation Ueenono Ammeyokoeyoko R2R2 Uenoeno Stationtation JR R2R2 Heeadad Ofccee Weekends and holidays only Ueno Sta. Route Map Showa St. R5R5 Ueenono MMatsuzakayaatsuzakaya There are many attractions at Ueno Park, ● Exit 8 *It is not a HOP BUS (Open deck Bus). including the Tokyo National Museum, as Yuushimashima Teenmangunmangu The shuttle bus services are available for the Sky Hop Bus ticket. well as the National Museum of Western Art. OkachimachiOkachimachi SSta.ta. Nearby is also the popular Yanesen area. It’s Akkihabaraihabara a great spot to walk around old streets while trying out various snacks. Marui Sooccerccer Muuseumseum Exit 4 ● R6R6 (Suuehirochoehirocho) Sumida River Ouurr Shhuttleuttle Buuss Seervicervice HibiyaLine Sta. Ueno Weekday 10:00-20:00 A Marunouchiarunouchi Shuttlehuttle Weekend/Holiday 8:00-20:00 ↑Mukojima R3R3 TOKYOTOKYO SSKYTREEKYTREE TOKYO SKYTREE Sta. Edo St. 4 Front Exit ● Metropolitan Expressway Stationtation TOKYO SKYTREE Kaandanda Shhrinerine 5 Akkihabaraihabara At Solamachi, which also serves as TOKYO Town Asakusa/TOKYO SKYTREE Course 1010 9 8 7 6 SKYTREE’s entrance, you can go shopping R3R3 1111 on the first floor’s Japanese-style “Station RedRed (1 trip 90 min./every 35 min.) Imperial coursecourse Theater Street.” Also don’t miss the fourth floor Weekday Asakusa St. -

Senkawa, Takamatsu, Chihaya, Kanamecho Ikebukuro Station's

Sunshine City is one of the largest multi-facility urban complex Ikebukuro Station is said to be one of the biggest railway terminals in Tokyo, Japan. in Japan. It consists of 5 buildings, including Sunshine It contains the JR Yamanote Line, the JR Saikyo Line, the Tobu Tojo Line, the Seibu Ikebukuro Ikebukuro Station’s 60, a landmark of Ikebukuro, at its center. It is made up of Line, Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line, Yurakucho Line, Fukutoshin Line, etc., Sunshine City shops and restaurants, an aquarium, a planetarium, indoor Narita Express directly connects Ikebukuro Station and Narita International Airport. West Exit theme parks etc., A variety of fairs and events are held at It is a very convenient place for shopping and people can get whichever they might require Funsui-hiroba (the Fountain Plaza) in ALPA. because the station buildings and department stores are directly connected, such as Tobu Department Store, LUMINE, TOBU HOPE CENTER, Echika, Esola, etc., Jiyu Gakuen Myōnichi-kan Funsui-hiroba (the Fountain Plaza) In addition, various cultural events are held at Tokyo Metropolitan eater and Ikebukuro Nishiguchi Park on the west side of Ikebukuro Station. A ten-minute-walk from the West Exit will bring you to historic buildings such as Jiyu Gakuen Myōnichi-kan, a pioneering school of liberal education for Japan’s women and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Rikkyo University, the oldest Christianity University, and the Former Residence of Rampo Edogawa, a leading author of Japanese detective stories. J-WORLD TOKYO Sunshine City Rikkyo University and “Suzukake-no- michi” ©尾 田 栄 一 郎 / 集 英 社・フ ジ テ レ ビ・東 映 ア ニ メ ー シ ョ ン Pokémon Center MEGA TOKYO Tokyo Yosakoi Former Residence of Rampo Edogawa Konica Minolta Planetarium “Manten” Sunshine Aquarium Senkawa, Takamatsu, NAMJATOWN Chihaya, Kanamecho Tokyo Metropolitan Theater Ikebukuro Station’s Until about 1950, there were many ateliers around this area, and young painters and East Exit sculptors worked hard.