The Installations and Ephemeral Art of David Wojnarowicz by John B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articulos/Articles Arte De Apropiación

Páginas de Filosofía, Año XVI, Nº 19 (enero-julio 2015), 80-95 Departamento de Filosofía, Universidad Nacional del Comahue ISSN: 0327-5108; e-ISSN: 1853-7960 http://revele.uncoma.edu.ar/htdoc/revele/index.php/filosofia/index ARTICULOS/ARTICLES ARTE DE APROPIACIÓN. RECONSIDERACIONES ALREDEDOR DEL PROBLEMA DE LOS INDISCERNIBLES EN DANTO APPROPRIATION ART: A REASSESSMENT OF DANTO'SAPPROACH TO THE PROBLEM OF INDISCERNIBLE COUNTERPARTS Gemma Argüello Manresa Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Lerma Resumen: En este trabajo se desarrollan los argumentos que Arthur Danto elaboró en torno al significado metafórico y el estilo con el objetivo de mostrar si es posible que su modelo permita comprender nuevas formas de Arte de Apropiación. Éstas engloban las prácticas recientes en las que los artistas hacen réplicas más o menos exactas de otras obras que han sido importantes en la historia del arte. Palabras clave: Arte de Apropiación, metáfora, estilo. Abstract: In this paper Arthur Danto’s arguments about metaphorical meaning and style are analyzed in order to show whether it is possible that his model works for understanding new ways of Appropriation Art. These are recent artistic practices in which artists make more or less accurate copies of other artworks that have been important in Art History. Keywords: Appropriation art, Metaphor, Style. Sobre el Arte de Apropiación y sus distintas formas En este trabajo me voy a concentrar en la forma en que Arthur Danto podría enfrentar ciertas prácticas contemporáneas de Arte de Apropiación, las cuales han pasado muchas veces desapercibidas por sus críticos, y que, de hecho, también serían ejemplos idóneos para abordar el problema de los indiscernibles en el arte, más que las obras de Warhol 81 ARTE DE APROPIACIÓN a las que Danto les tuvo tanta estima. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

Sampling Real Life: Creative Appropriation in Public Spaces

Sampling Real Life: Creative Appropriation in Public Spaces Elsa M. Lankford Electronic Media & Film (EMF) Towson University [email protected] I. Introduction Enter an art museum or a library and you will find numerous examples of appropriation, all or most of which were most likely legal at the time. From the birth of copyright and the idea that an author, encompassed as a writer, artist, composer, or musician, is the creator of a completely original work, our legal and moral perceptions of appropriation have changed. Merriam-Webster defines appropriation in multiple ways, two of which apply to the discussion of art and appropriation. The first, “to take exclusive possession of” and the second “to take or make use of without authority or right.”1 The battle over rights and appropriation is not one that is only fought in the courtroom and gallery, it also concerns our own lives. Many aspects of our lives involve appropriation, from pagan holidays appropriated into the Christian calendar to the music we listen to, even to the words we speak or write appropriated from other countries and cultures. As artists, appropriation in many forms makes its way into works of any media. The topic of appropriation leads to a discussion of where our creative ideas come from. They, in some sense, have been appropriated as well. Whether we overhear a snippet of a conversation that ends up woven into a creative work or we take a picture of somebody, unknowingly, as they walk down a tree-shadowed street, we are appropriating life. For centuries, artists have been inspired by public life, and the stories and images of others have been appropriated into their work. -

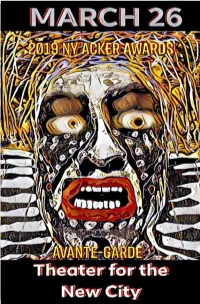

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

David Wojnarowicz and the Surge of Nuances. Modifying Aesthetic Judgment with the Influx of Knowledge

David Wojnarowicz and the Surge of Nuances. Modifying Aesthetic Judgment with the Influx of Knowledge Author Affiliation Paul R. Abramson & University of California, Tania L. Abramson Los Angeles Abstract: Learning that an artist was a victim of inconceivable torment is critical to how their artworks are experienced. Forced as it were to absorb the wretched demons from the here and now, artists such as David Wojnarowicz have implau- sibly found the resolve to depict this adversity, and its psychological detritus, in their singularly creative manners. Recognised for his autobiographical writings no less than his artwork, Wojnarowicz is especially admired for his sheer defiance of conventional life scripts, and his fortitude in the face of adversity in the circum- scribed world of imaginative constructions. Arthur Rimbaud in New York, A Fire in My Belly, and Wind (for Peter Hujar) for example. The enduring value of his artwork, inextricably enhanced by his diaries and essays, is that they simultane- ously provide a narrative portal into the untangling of his inner life, as well as fundamentally influence how these works are perceived. When looking at two paintings, ostensibly by Rembrandt, is there an aesthetic difference in how these paintings are experienced if we know that one of the two paintings is a forgery? Most certainly, declared Nelson Goodman, who noted that this bit of knowledge ‘makes the consequent demands that modify and differentiate my present experience in looking at the two [Rembrandt] paintings’.1 Is that also true about depictions of Christ on the cross? Does knowledge of Christ’s story alter how Michelangelo’s Christ on the Cross is experienced? If what we know, or think we know, has the capacity to ultimately influence © Aesthetic Investigations Vol 3, No 1 (2020), 146-157 Paul R. -

Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, No

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Peter R. Kalb, review of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11870. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation Curated by: Liz Munsell, The Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, and Greg Tate Exhibition schedule: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, October 18, 2020–July 25, 2021 Exhibition catalogue: Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, eds., Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020. 199 pp.; 134 color illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780878468713) Reviewed by: Peter R. Kalb, Cynthia L. and Theodore S. Berenson Chair of Contemporary Art, Department of Fine Arts, Brandeis University It may be argued that no artist has carried more weight for the art world’s reckoning with racial politics than Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988). In the 1980s and 1990s, his work was enlisted to reflect on the Black experience and art history; in the 2000 and 2010s his work diversified, often single-handedly, galleries, museums, and art history surveys. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation attempts to share in these tasks. Basquiat’s artwork first appeared in lower Manhattan in exhibitions that poet and critic Rene Ricard explained, “made us accustomed to looking at art in a group, so much so that an exhibit of an individual’s work seems almost antisocial.”1 The earliest efforts to historicize the East Village art world shared this spirit of sociability. -

Environmental & Ephemeral Art

ART LESSONS at HOME week 1- *optional* enrichment Environmental & Ephemeral Art ~with Mrs. Hemmis This week we will be learning about environmental and ephemeral art. We will become familiar with 3 environmental artists. We will learn to identify and define the characteristics of environmental art. We will learn what it means for art to be ephemeral. We will create a work of environmental art using materials that we find in our environments. *Optional: We can create a memory of our work of art using sketching or photography. We will create an artist statement to describe the process of creating a work of art. What is environmental art? Environmental art is art that is created using materials from our environments (the surroundings in which we live). Traditionally, environmental art is created using materials like: sticks rocks ice mud leaves nuts/seeds earth flowers What does it mean for art to be ephemeral? It means that it is not designed or meant to last forever. It is meant to change or fade away. You may have already created ephemeral art. Have you ever made a sandcastle, snowperson, lego sculpture, block tower? Those are all examples of ephemeral art, because they don’t last forever. 3 Significant Environmental Artists to know: Robert Smithson Andrew Goldsworthy Maya Lin Andrew Goldsworthy Andy Goldsworthy was born the 26th of July 1956, in Cheshire, England. He lives and works in Scotland in a village called Penpont. ... Andy Goldsworthy produces artwork using natural materials (such as flowers, mud, ice, leaves, twigs, pebbles, boulders, snow, thorns, bark, grass and pine cones) Maya Lin Maya Ying Lin (born October 10, 1959) is a Chinese-American architect and artist. -

John Lurie/Samuel Delany/Vladimir Mayakovsky/James Romberger Fred Frith/Marty Thau/ Larissa Shmailo/Darius James/Doug Rice/ and Much, Much More

The World’s Greatest Comic Magazine of Art, Literature and Music! Number 9 $5.95 John Lurie/Samuel Delany/Vladimir Mayakovsky/James Romberger Fred Frith/Marty Thau/ Larissa Shmailo/Darius James/Doug Rice/ and much, much more . SENSITIVE SKIN MAGAZINE is also available online at www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com. Publisher/Managing Editor: Bernard Meisler Associate Editors: Rob Hardin, Mike DeCapite & B. Kold Music Editor: Steve Horowitz Contributing Editors: Ron Kolm & Tim Beckett This issue is dedicated to Chris Bava. Front cover: Prime Directive, by J.D. King Back cover: James Romberger You can find us at: Facebook—www.facebook.com/sensitiveskin Twitter—www.twitter.com/sensitivemag YouTube—www.youtube.com/sensitiveskintv We also publish in various electronic formats (Kindle, iOS, etc.), and have our own line of books. For more info about SENSITIVE SKIN in other formats, SENSITIVE SKIN BOOKS, and books, films and music by our contributors, please go to www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/store. To purchase back issues in print format, go to www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/back-issues. You can contact us at [email protected]. Submissions: www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/submissions. All work copyright the authors 2012. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of both the publisher and the copyright owner. All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. ISBN-10: 0-9839271-6-2 Contents The Forgetting -

Pitman, Sophie; Smith, Pamela ; Uchacz, Tianna; Taape, Tillmann; Debuiche, Colin the Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, Spectacle, and Power in Early Modern Europe

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. Pitman, Sophie; Smith, Pamela ; Uchacz, Tianna; Taape, Tillmann; Debuiche, Colin The Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, spectacle, and power in early modern Europe Published in: RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY DOI: 10.1017/rqx.2019.496 Published: 01/01/2020 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please cite the original version: Pitman, S., Smith, P., Uchacz, T., Taape, T., & Debuiche, C. (2020). The Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, spectacle, and power in early modern Europe. RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY, 73(1), 78-131. [0034433819004962]. https://doi.org/10.1017/rqx.2019.496 This material is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) The Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, Spectacle, and Power in Early Modern Europe PAMELA H. SMITH, Columbia University TIANNA HELENA UCHACZ, Columbia University SOPHIE PITMAN, Aalto University TILLMANN TAAPE, Columbia University COLIN DEBUICHE, University of Rennes Through a close reading and reconstruction of technical recipes for ephemeral artworks in a manu- script compiled in Toulouse ca. 1580 (BnF MS Fr. 640), we question whether ephemeral art should be treated as a distinct category of art. -

Power in the Discourse of Art: Ephemeral Arts As Counter-Monuments

Power in the Discourse of Art: Ephemeral Arts as Counter-Monuments Kuninori (Shoso) Shimbo, Monash University, Australia The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This study investigates how transience is articulated in contemporary sculpture, in particular ephemeral art. In the art industry, ephemeral art does not generally enjoy the similar prestige as archived art partly due to the difficulties in preserving it. There is discussion that ephemeral art is often relegated to the post-structuralist descendent position, as opposed to being in the traditionally powerful ascendent position for ar- chived art. However, such a relationship of power has been questioned in various dis- courses in contemporary art since ephemeral art provides contemporary artists with alternative visions and various possibilities. Especially with socio-cultural changes including the development of postcolonial consciousness and feminism, the role of monumental sculptures as effective carriers of memory and meaning in our time is disputed, whereas ephemeral art as anti-monument or counter-monument has been pointed out to be able to deconstruct traditional forms of monuments. Another strong contradiction to archived art is proposed by some artists who regard transience as a way of being. They generally investigate ephemerality as a central nature of their works. Their approaches often show an interesting proximity to the traditional Japa- nese aesthetics. This study shows that ephemeral art provides contemporary artists with alternative approaches and various possibilities. Keywords: Installation, Ephemeral art, Anti-monument, Transience, Ikebana iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Introduction This study investigated how transience is articulated in contemporary sculpture, spe- cifically in ephemeral art. -

82 SECOND AVENUE 1,150 SF Availble for Lease Between East 4Th and 5Th Streets EAST VILLAGE NEW YORK | NY

RETAIL SPACE 82 SECOND AVENUE 1,150 SF Availble for Lease Between East 4th and 5th Streets EAST VILLAGE NEW YORK | NY SPACE A SPACE B SPACE DETAILS GROUND FLOOR LOWER LEVEL LOCATION NEIGHBORS Between East 4th and 5th Streets Nomad, Atlas Café, Frank, The Mermaid Inn, Coopers Craft & SIZE Kitchen, Bank Ant, The Bean Space A COMMENTS EXISTING Ground Floor 700 SF Prime East Village restaurant WALK-IN Basement 300 SF opportunity SPACE A REFRIGERATOR 300 SF Space B Vented for cooking use; gas and electric in place Ground Floor 450 SF KITCHEN New direct long-term lease, Basement 200 SF no key money FRONTAGE Space A Second Avenue 12 FT Space B Second Avenue 10 FT SPACE A TRANSPORTATION 700 SF 2019 Ridership Report Second Avenue Astor Place 6 RESTAURANT Annual 5,583,944 Annual 5,502,925 Weekday 16,703 Weekday 17,180 Weekend 24,564 Weekend 21,108 12 FT SECOND AVENUE EAST 14TH STREET EAST 14TH STREET EAST 14TH STREET EAST 14TH STREET WEST 14TH STREET EAST 14TH STREET Optyx Artichokes Pizza Petopia Akina Sushi Muzarella Pizza Bright Horizons Brothers Candy & Grocery M&J Nature Joe’s Pizza Krust Lex AMALGAMATED Vanessa’s Regina The City Synergy AVENUE SECOND Taverna Kyclades Republic Dumplings AVENUE FIRST Exchange AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS AVENUE Champion BANK Pizza Check Nugget Gourmet Big Arc Chicken AVENUE C AVENUE AVENUE A AVENUE Wine & City Le Café Coee B AVENUE Pizza First Lamb King’s Way Cashing Spot Baohaus Tortuga Vinny Vicenz Jewelry Spirits AVENUE THIRD Planet Rose FIFTH AVENUE Streets Cava Grill Revolution Shabu Food Corp Discount PJ’s Grocery -

David Wojnarowicz. History Keeps Me Awake at Night

David Wojnarowicz. History Keeps Me Awake at Night DATES: 29 May – 30 September, 2019 PLACE: Sabatini Building, Floor 1 ORGANIZATION: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in collaboration with the Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, and the Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Luxembourg CURATORSHIP: David Breslin and David Kiehl COORDINATION: Rafael García TOUR: Whitney Museum of American Art, Nueva York: 13 July– 30 September, 2018 Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid: 29 May – September 30, 2019 Mudam Luxembourg - Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Luxemburg: 26 October, 2019 – 2 February 2020 The exhibition David Wojnarowicz. History Keeps Me Awake at Night is the first major review of the multifaceted creative work of the artist, writer and activist David Wojnarowicz (New Jersey, 1954-New York, 1992) since the 1999 exhibition at the New Museum in New York and the 2012 publication of Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz, his Cynthia Carr's detailed biography. This major retrospective, organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in collaboration with the Reina Sofia Museum and the Mudam Luxembourg - Musée d'Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, not only examines the plurality of styles and media that the artist displayed in his practice, but also relates his work to the political, social and artistic context of New York in the 1980s and early 1990s. That was a time marked by economic uncertainty and the terrible AIDS epidemic, but also by creative energy and a series of profound cultural changes: the intersection of different movements - graffiti, new wave and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance and neo-expressionist painting - turned the American city into an artistic laboratory for innovation.