XFR STN: the New Museum's Stone Tape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

LOOKING AT MUSIC: SIDE 2 EXPLORES THE CREATIVE EXCHANGE BETWEEN MUSICIANS AND ARTISTS IN NEW YORK CITY IN THE 1970s AND 1980s Photography, Music, Video, and Publications on Display, Including the Work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Blondie, Richard Hell, Sonic Youth, and Patti Smith, Among Others Looking at Music: Side 2 June 10—November 30, 2009 The Yoshiko and Akio Morita Gallery, second floor Looking at Music: Side 2 Film Series September—November 2009 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, June 5, 2009—The Museum of Modern Art presents Looking at Music: Side 2, a survey of over 120 photographs, music videos, drawings, audio recordings, publications, Super 8 films, and ephemera that look at New York City from the early 1970s to the early 1980s when the city became a haven for young renegade artists who often doubled as musicians and poets. Art and music cross-fertilized with a vengeance following a stripped-down, hard-edged, anti- establishment ethos, with some artists plastering city walls with self-designed posters or spray painted monikers, while others commandeered abandoned buildings, turning vacant garages into makeshift theaters for Super 8 film screenings and raucous performances. Many artists found the experimental music scene more vital and conducive to their contrarian ideas than the handful of contemporary art galleries in the city. Artists in turn formed bands, performed in clubs and non- profit art galleries, and self-published their own records and zines while using public access cable channels as a venue for media experiments and cultural debates. Looking at Music: Side 2 is organized by Barbara London, Associate Curator, Department of Media and Performance Art, The Museum of Modern Art, and succeeds Looking at Music (2008), an examination of the interaction between artists and musicians of the 1960s and early 1970s. -

A Retrospective of Preservation Practice and the New York City Subway System

Under the Big Apple: a Retrospective of Preservation Practice and the New York City Subway System by Emma Marie Waterloo This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Tomlan,Michael Andrew (Chairperson) Chusid,Jeffrey M. (Minor Member) UNDER THE BIG APPLE: A RETROSPECTIVE OF PRESERVATION PRACTICE AND THE NEW YORK CITY SUBWAY SYSTEM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Emma Marie Waterloo August 2010 © 2010 Emma Marie Waterloo ABSTRACT The New York City Subway system is one of the most iconic, most extensive, and most influential train networks in America. In operation for over 100 years, this engineering marvel dictated development patterns in upper Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. The interior station designs of the different lines chronicle the changing architectural fashion of the aboveground world from the turn of the century through the 1940s. Many prominent architects have designed the stations over the years, including the earliest stations by Heins and LaFarge. However, the conversation about preservation surrounding the historic resource has only begun in earnest in the past twenty years. It is the system’s very heritage that creates its preservation controversies. After World War II, the rapid transit system suffered from several decades of neglect and deferred maintenance as ridership fell and violent crime rose. At the height of the subway’s degradation in 1979, the decision to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the opening of the subway with a local landmark designation was unusual. -

Design a Subway Station Mosaic That Reflects Their Home Or School Neighborhood and Draw It

MILES OF TILES MILES OF TILES BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS “Design and aesthetics have been a part of the subway from the original stations of 1904 to the latest work in 2018. But nothing in New York stands still – certainly not the subway - and the approach to subway style has evolved, reflecting the major stages of the system’s construction during the early 1900s, the teens, and the late 20s and early 30s and the renovations and redesigns of later years. The earliest parts of the system still convey the flowery, genteel flavor of a smaller, older city. Later sections, by contrast, show a conscious turn toward the modern, including open admiration for the system’s raw structural power. The evolution of subway design follows the trajectory of the world of art and architecture as these came to terms with the Industrial revolution, and the tug-of-war between a traditional deference to European models and a modernist ideology demanding an honest expression of contemporary industrial technology.” —Subway style: 100 years of Architecture & Design in the New York City Subway New York City, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was an industrial hub attracting many Americans from rural communities looking for work, and immigrants looking for better lives. It was, however, blighted by impoverished neighborhoods of broken down tenements and social injustice. The city lacked a plan for how it should look, where structures should be built, or how services should be distributed. It was described as a ‘ragged pincushion of towers’ with no government regulation over the urban landscape. -

Xfr Stn: Public Programs

XFR STN: PUBLIC PROGRAMS 7/25 | 7 PM | FIFTH FLOOR PANEL DISCUSSIONS LIZA BÉAR & MILLY IATROU, 7/18 | 6 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER COMMUNICATIONS UPDATE MOVING IMAGE ARTISTS’ The weekly artist public access Communications DISTRIBUTION THEN & NOW Update, later renamed Cast Iron TV, ran continuously on Manhattan Cable’s Channel D from 1979 to 1991. Filmmakers Liza Béar and Milly Iatrou present indi- An assembly of participants from the MWF Video Club vidual segments cablecast in the Communications and Colab TV projects includes opening remarks from Update 1982 series: “The Very Reverend Deacon b. Alan W. Moore, Andrea Callard, Michael Carter, Coleen Peachy,” “A Matter of Facts,” “Crime Tales,” “Lighter Fitzgibbon, Nick Zedd, and members of the New Than Air,” and “Oued Nefifik: A Foreign Movie.” Museum’s “XFR STN” team. Followed by an open dis- cussion with the audience, facilitated by Alexis Bhagat. 8/1 | 7–8 PM | FIFTH FLOOR MITCH CORBER, THE ORIGINAL 9/7 | 1 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER WONDER ALWAYS ALREADY OBSOLETE: MEDIA CONVERGENCE, ACCESS, Mitch Corber has dedicated his career to production for NYC public access cable TV, working closely with AND PRESERVATION Colab TV and the MWF Video Club. Corber will present a selection of early work, as well as videos from his Beyond media specificity, what happens after video- long-running program Poetry Thin Air. tape has been absorbed into a new medium—and what are the implications of these continuing shifts in format for how we understand access and preserva- 8/8 | 7 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER tion? This panel considers forms of preservation that have emerged across analog, digital, and networked CLAYTON PATTERSON: platforms in conjunction with new forms of circulation FROM THE UNDERGROUND AND and distribution. -

New York, New York

EXPOSITION NEW YORK, NEW YORK Cinquante ans d’art, architecture, cinéma, performance, photographie et vidéo Du 14 juillet au 10 septembre 2006 Grimaldi Forum - Espace Ravel INTRODUCTION L’exposition « NEW YORK, NEW YORK » cinquante ans d’art, architecture, cinéma, performance, photographie et vidéo produite par le Grimaldi Forum Monaco, bénéficie du soutien de la Compagnie Monégasque de Banque (CMB), de SKYY Vodka by Campari, de l’Hôtel Métropole à Monte-Carlo et de Bentley Monaco. Commissariat : Lisa Dennison et Germano Celant Scénographie : Pierluigi Cerri (Studio Cerri & Associati, Milano) Renseignements pratiques • Grimaldi Forum : 10 avenue Princesse Grace, Monaco – Espace Ravel. • Horaires : Tous les jours de 10h00 à 20h00 et nocturne les jeudis de 10h00 à 22h00 • Billetterie Grimaldi Forum Tél. +377 99 99 3000 - Fax +377 99 99 3001 – E-mail : [email protected] et points FNAC • Site Internet : www.grimaldiforum.mc • Prix d’entrée : Plein tarif = 10 € Tarifs réduits : Groupes (+ 10 personnes) = 8 € - Etudiants (-25 ans sur présentation de la carte) = 6 € - Enfants (jusqu’à 11 ans) = gratuit • Catalogue de l’exposition (versions française et anglaise) Format : 24 x 28 cm, 560 pages avec 510 illustrations Une coédition SKIRA et GRIMALDI FORUM Auteurs : Germano Celant et Lisa Dennison N°ISBN 88-7624-850-1 ; dépôt légal = juillet 2006 Prix Public : 49 € Communication pour l’exposition : Hervé Zorgniotti – Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 02 – [email protected] Nathalie Pinto – Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 03 – [email protected] Contact pour les visuels : Nadège Basile Bruno - Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 25 – [email protected] AUTOUR DE L’EXPOSITION… Grease Etes-vous partant pour une virée « blouson noir, gomina et look fifties» ? Si c’est le cas, ne manquez pas la plus spectaculaire comédie musicale de l’histoire du rock’n’roll : elle est annoncée au Grimaldi Forum Monaco, pour seulement une semaine et une seule, du 25 au 30 juillet. -

Faculty and Staff Activities 2014–2015

FACULTY AND STAFF ACTIVITIES 2014–2015 COOPER AT ARCHITECTURE Professor Diana Agrest’s film “The Making of an Avant- Assistant Professor Adjunct John Hartmann, co-founder Visiting Professor Joan Ockman was a co-editor for MAS: Garde: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies with Lauren Crahan of Freecell Architecture, spoke at The The Modern Architecture Symposia 1962-1966: A Critical Edition 1967-1984” was screened at the Graham Foundation, Hammons School of Architecture at Drury University as part (Yale University Press). The publication was reviewed in Princeton University, Cornell University, UC Berkeley of the 2014-2015 Lecture Series. Architectural Record. She was a presenter at The Building EDITED BY EMMY MIKELSON; DESIGN BY INESSA SHKOLNIKOV, CENTER FOR DESIGN AND TYPOGRAPHY; PHOTOGRAPHY BY JOÃO ENXUTO WITH SPECIAL ASSISTANCE FROM THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE ARCHIVE AND ELIZABETH O’DONNELL, ACTING DEAN ARCHIVE AND ELIZABETH O’DONNELL, ACTING FROM THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE WITH SPECIAL ASSISTANCE ENXUTO BY JOÃO DESIGN AND TYPOGRAPHY; PHOTOGRAPHY CENTER FOR SHKOLNIKOV, EDITED BY EMMY MIKELSON; DESIGN INESSA College of Environmental Design and followed by a panel Symposium held at Columbia University GSAPP. discussion with Agrest, Nicholas de Monchaux, Sylvia Lavin Director of the School of Architecture Archive, and Stanley Saitowitz, the 10th Annual Cinema Orange Film Steven Hillyer, co-produced Christmas Without Tears, Acting Dean and Professor Elizabeth O’Donnell was the Series, Newport Beach Film Festival at Orange County a four-city tour of holiday-themed variety shows hosted co-chair and delivered the introductory remarks for Museum of Art, the San Diego Design Film Festival, and Cite by Judith Owen and Harry Shearer, which included “The Sultanate of Oman: Geography, Religion and Culture” de l’Architecture in Paris, France, which was followed by a performances by Mario Cantone, Catherine O’Hara, held at The Cooper Union. -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

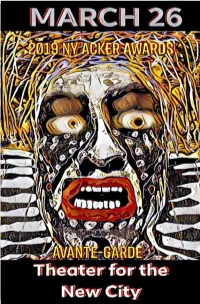

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

The New York City Subway

John Stern, a consultant on the faculty of the not-for-profit Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York City, and a graduate of Columbia University, has had a lifelong interest in architecture, history, geology, cities, and transportation. He was a senior planner for the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission in New York, and is an Honorary Director of the Shore Line Trolley Museum in Connecticut. His extensive photographs of streetcar systems in dozens of American and Canadian cities during the late 1940s, '50s, and '60s comprise a major portion of the Sprague Library's collection. Mr. Stern resides in New York City with his wife, Faith, who is also a consultant of Aesthetic Realism, the education founded by the American poet and critic Eli Siegel (1902-1978). His public talks include seminars on Fiorello LaGuardia and Robert Moses, and "The Brooklyn Bridge: A Study in Greatness," written with consultant and art historian Carrie Wilson, which was presented at the bridge's 120th anniversary celebration in 2003, and the 125th anniversary in 2008. The paper printed here was given at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, 141 Greene Street in NYC on October 23rd and at the Queens Public Library in Flushing in 2006. The New York Subway: A Century By John Stern THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27, 1904 was a gala day in the City of New York. Six hundred guests assembled inside flag-bedecked City Hall listened to speeches extolling the brand-new subway, New York's first. After the last speech, Mayor George B. McClellan spoke, saying, "Now I, as Mayor, in the name of the people, declare the subway open."1 He and other dignitaries proceeded down into City Hall station for the inau- gural ride up the East Side to Grand Central Terminal, then across 42nd Street to Times Square, and up Broadway to West 145th Street: 9 miles in all (shown by the red lines on the map). -

Oral History Interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington, 2009 January 21 and May 22

Oral history interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington, 2009 January 21 and May 22 Funding for this interview was provided by the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington on January 21 and May 22, 2009. The interview took place at in New York, New York, and was conducted by James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by a grant from the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Wendy Olsoff, Penny Pilkington, and James McElhinney have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JAMES McELHINNEY: This is James McElhinney speaking with Penny Pilkington and Wendy Olstroff. PENNY PILKINGTON: Olsoff. O-L-S-O-F-F. MR. McELHINNEY: Olsoff? WENDY OLSOFF: Right. MR. McELHINNEY: At 432 Lafayette Street in New York, New York, on January 21, 2009. So for the transcriber, I’m going to ask you to just simply introduce yourselves so that the person who is writing out the interview will be able to identify— [END OF DISC 1, TRACK 1.] MR. McELHINNEY: —who’s who by voice. -

Anthology Film Archives 104

242. Sweet Potato PieCl 384. Jerusalem - Hadassah Hospital #2 243. Jakob Kohn on eaver-Leary 385. Jerusalem - Old Peoples Workshop, Golstein Village THE 244. After the Bar with Tony and Michael #1 386. Jerusalem - Damascus Gate & Old City 245. After the Bar with Tony and Michael #2 387. Jerusalem -Songs of the Yeshiva, Rabbi Frank 246. Chiropractor 388. Jerusalem -Tomb of Mary, Holy Sepulchre, Sations of Cross 247. Tosun Bayrak's Dinner and Wake 389. Jerusalem - Drive to Prison 248. Ellen's Apartment #1 390. Jerusalem - Briss 249. Ellen's Apartment #2 391 . European Video Resources 250. Ellen's Apartment #3 392. Jack Moore in Amsterdam 251, Tuli's Montreal Revolt 393. Tajiri in Baarlo, Holland ; Algol, Brussels VIDEOFIiEEX Brussels MEDIABUS " LANESVILLE TV 252. Asian Americans My Lai Demonstration 394. Video Chain, 253. CBS - Cleaver Tapes 395. NKTV Vision Hoppy 254. Rhinoceros and Bugs Bunny 396. 'Gay Liberation Front - London 255. Wall-Gazing 397. Putting in an Eeel Run & A Social Gathering 256. The Actress -Sandi Smith 398. Don't Throw Yer Cans in the Road Skip Blumberg 257. Tai Chi with George 399. Bart's Cowboy Show 258. Coke Recycling and Sheepshead Bay 400. Lanesville Overview #1 259. Miami Drive - Draft Counsel #1 401 . Freex-German TV - Valeska, Albert, Constanza Nancy Cain 260. Draft Counsel #2 402, Soup in Cup 261 . Late Nite Show - Mother #1 403. Lanesville TV - Easter Bunny David Cort 262. Mother #2 404. LanesvilleOverview #2 263. Lenneke and Alan Singing 405. Laser Games 264. LennekeandAlan intheShower 406. Coyote Chuck -WestbethMeeting -That's notRight Bart Friedman 265. -

Schor Moma Moma

12/12/2016 M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 H O M E A B O U T L I N K S Browse: Home / 2016 / December / 09 / M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking CONNE CT 3 Mira's Facebook Page DE CE MBE R 9 , 2 0 1 6 Subscribe in a Reader Subscribe by email M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 miraschor.com The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, TAGS Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and 2016 election Abstract politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and Expressionism ACTUAW poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to. Activism Ana Mendieta Andrea For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some longtime contributors Geyer Andrea Mantegna Anselm and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning Kiefer Barack Obama CalArts craft today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the Cubism DAvid Salle documentary concerns that have the most meaning to them right now. film drawing Edwin Denby Facebook feminism Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will Feminist art appear on A Year of Positive Thinking.