To Download a Free Study Guide for Thieves In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruxy Cavey and the Meeting House Megachurch: a Dramaturgical Model of Charismatic Leadership Performing “Evangelicalism for People Not Into Evangelicalism”

Bruxy Cavey and The Meeting House Megachurch: A Dramaturgical Model of Charismatic Leadership Performing “Evangelicalism for People Not Into Evangelicalism” by Peter Schuurman A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Peter Schuurman 2016 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ! ii ! Abstract Megachurch pastors—as local and international celebrities—have been a growing phenomenon since the 1960s, when megachurches began to proliferate across North America. Why are these leaders and their large congregations so popular in an age of increasing “religious nones”? Commentators in both popular and academic literature often resort to characterizing the leadership with stereotypes of manipulative opportunists along the lines of Sinclair Lewis’ Elmer Gantry (1927) or narrow characterizations of savvy entrepreneurs who thrive in a competitive religious economy. Similarly, writers assume megachurch attendees are a passive audience, or even dupes. This dissertation challenges the Elmer Gantry stereotype and the religious economic perspectives by examining one particular megachurch pastor named Bruxy Cavey in the context of his “irreligious” megachurch community called -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 4-2-2009 The aC rroll News- Vol. 85, No. 19 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 85, No. 19" (2009). The Carroll News. 788. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/788 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Russert Fellowship Tribe preview NBC creates fellowship in How will Sizemore and honor of JCU grad, p. 3 the team stack up? p. 15 THE ARROLL EWS Thursday,C April 2, 2009 Serving John Carroll University SinceN 1925 Vol. 85, No. 19 ‘Help Me Succeed’ library causes campus controversy Max Flessner Campus Editor Members of the African The African American Alliance had to move quickly to abridge an original All-Stu e-mail en- American Alliance Student Union try they had sent out requesting people to donate, among other things, copies of old finals and mid- Senate votes for terms, to a library that the AAA is establishing as a resource for African American students on The ‘Help Me administration policy campus. The library, formally named the “Help Me Suc- Succeed’ library ceed” library, will be a collection of class materials to close main doors and notes. The original e-mail that was sent in the March to cafeteria 24 All-Stu, asked -

Mobile Overall Score Reports

Mobile Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Performance Double Platinum 1 354 Wipe Out - Creative Dance and Gymnastics - Moss Point, MS 114.0 Gracie Newbill Platinum 1st Place 2 56 Birthday - Premiere Dance Studio - Mt Vernon, AL 109.9 Morgan Dixon Platinum 1st Place 3 79 Hey Baby - Tiffany & Co. Dance Studio - Metairie, LA 109.8 Skye Rogers Platinum 1st Place 3 355 Boots - Creative Dance and Gymnastics - Moss Point, MS 109.8 Taylor Ortiz Platinum 1st Place 4 171 Tea Party - Gulf Coast Dance Alliance - Spanish Fort, AL 109.4 Keeley Bulman Platinum 1st Place 4 392 Heaven - Broadway South Dance - Mobile, AL 109.4 Bella Tumminello Gold 1st Place 5 393 Born to Entertain - Broadway South Dance - Mobile, AL 108.4 Haylie Gullitch Gold 1st Place 6 78 Call Me a Princess - Tiffany & Co. Dance Studio - Metairie, LA 108.3 Mattie DeBram Gold 1st Place 6 474 Anything You Can Do I Can Do Better - Pat Gray Academy - Meridian, MS 108.3 Madison Barefield Gold 1st Place 7 169 Rockin' Robin - Gulf Coast Dance Alliance - Spanish Fort, AL 108.2 Stella Waters Gold 1st Place 8 120 Fly to Your Heart - Footprints Christian Academy of Dance - Loranger, LA 107.7 Brianna Bergeron Gold 1st Place 8 550 Show Off - Southern Strutt - Robertsdale, AL 107.7 Josie Rivera Gold 1st Place 9 475 Believe - Pat Gray Academy - Meridian, MS 106.9 Isbella Mathis Gold 1st Place 10 479 Get Your Sparkle On - Pat Gray Academy - Meridian, MS 106.4 Reagan Barefield Advanced Double Platinum 1 516 Cooties - Mann Dance Studio - Prattville, AL 111.4 Bailee Lightsey Platinum 1st -

Prince Talks and with the Release of 'Graffiti Bridge,' the Soundtrack to His Forthcoming Movie Musical, the Critics Are Listening

Prince Talks And with the release of 'Graffiti Bridge,' the soundtrack to his forthcoming movie musical, the critics are listening. But don't even try to take notes. Prince performing at Wembley, London, August 22nd, 1990. Graham Wiltshire/Hulton Archive/Getty By Neal Karlen October 18, 1990 The phone rings at 4:48 in the morning. "Hi, it's Prince," says the wide-awake voice calling from a room several yards down the hallway of this London hotel. "Did I wake you up?" Though it's assumed that Prince does in fact sleep, no one on his summer European Nude Tour can pinpoint precisely when. Prince seems to relish the aura of night stalker; his vampire hours have been a part of his mad-genius myth ever since he was waging junior-high-school band battles on Minneapolis's mostly black North Side. "Anyone who was around back then knew what was happening," Prince had said two days earlier, reminiscing. "I was working. When they were sleeping, I was jamming. When they woke up, I had another groove. I'm as insane that way now as I was back then." For proof, he'd produced a crinkled dime-store notebook that he carries with him like Linus's blanket. Empty when his tour started in May, the book is nearly full, with twenty-one new songs scripted in perfect grammar-school penmanship. He has also been laboring on the road over his movie musical Graffiti Bridge, which was supposed to be out this past summer and is now set for release in November. -

Dig If You Will the Picture

Barrelhouse Magazine Dig if You Will the Picture Writers Reflect on Prince First published by Barrelhouse Magazine in 2016. Copyright © Barrelhouse Magazine, 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher. It is illegal to copy this book, post it to a website, or distribute it by any others means without permission. This book was professionally typeset on Reedsy. Find out more at reedsy.com Contents Prince Rogers Nelson v The Beautiful Ones 7 The Birthday Suit 9 Freak 13 When the Cicadas Were Out of Their Fucking Minds 16 Two Poems After Prince 19 Try to Imagine What Silence Looks Like 24 And This Brings Us Back to Pharoah 27 Chant for a New Poet Generation 29 Trickster 31 Let's Go Crazy 36 Seventeen in '84 39 Elegy 41 Could Have Sworn It Was Judgement Day 43 Prince Called Me Up Onstage at the Pontiac Silverdome 47 Backing Up 49 The King of Purple 54 What It Is 55 I Shall Grow Purple 59 Group Therapy: Writers Remember Prince 61 Anthem for Paisley Park 77 Liner Notes 78 Nothing Compares 2 U 83 3 Because They Was Purple 88 Reign 90 Contributors 91 About Barrelhouse 101 Barrelhouse Editors 103 Prince Rogers Nelson June 7, 1958 – April 21, 2016 (art by Shannon Wright) In this life, things are much harder than in the afterworld. In this life, you're on your own. v 1 The Beautiful Ones by Sheila Squillante We used to buy roasted chickens at the Grand Union after school and take them back to Jen’s house. -

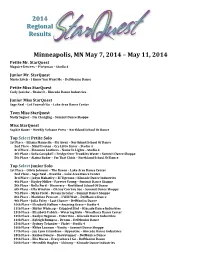

2014 Minneapolis Results

222000111444 RRReeegggiiiooonnnaaalll RRReeesssuuullltttsss Minneapolis, MN May 7, 2014 – May 11, 2014 Petite Mr. StarQuest Maguire Dewees – PArtyman – Studio 4 Junior Mr. StarQuest Mario Esteb – I Know You Want Me – DelMonico Dance Petite Miss StarQuest Carly Janicke – Shake It – Kincade Dance Industries Junior Miss StarQuest Sage Neal – Let Yourself Go – Lake Area Dance Center Teen Miss StarQuest Molly Segner – I’m Changing – Summit Dance Shoppe Miss StarQuest Sophie Bauer – Weekly Volcano Press – Northland School Of Dance Top Select Petite Solo 1st Place – Elliana Mannella – Fly Away – Northland School Of Dance 2nd Place – Mini Preston – Cry Little Sister – Studio 4 3rd Place – Eleanora Leathers – Name In Lights – Studio 4 4th Place – Sofia Campbell – Bridge OVer Troubles Water – Summit Dance Shoppe 5th Place – Alaina Bader – I’m That Chick – Northland School Of Dance Top Select Junior Solo 1st Place – OliVia Johnson – The RaVen – Lake Area Dance Center 2nd Place – Sage Neal – Breathe – Lake Area Dance Center 3rd Place – Jadyn Mahaffey – El Tigeraso – Kincade Dance Industries 4th Place – Hayley Miller – ForeVer Young – Summit Dance Shoppe 5th Place – Bella Ford – DiscoVery – Northland School Of Dance 6th Place – Ella Winston – Oh Say Can You See – Summit Dance Shoppe 7th Place – Myka Field – Dream In Color – Summit Dance Shoppe 8th Place – Madeline Prescott – I Will Wait – DelMonico Dance 9th Place – Julia Foley – Last Chance – DelMonico Dance 10th Place – Elizabeth Hallum – Amazing Grace – Studio 4 11th Place – Skylar Wishcop – Crippled -

Watch That Man: Gender Representation and Queer Performance in Glam Rock

Watch That Man: Gender Representation and Queer Performance in Glam Rock Hannah Edmondson Honors Thesis Department of English Spring 2019 Thesis Adviser: Dr. Graig Uhlin Second Reader: Dr. Jeff Menne TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………..…… 3 I. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….… 4 II. “Hang On To Yourself”: Glam Rock’s Persona Play…………………………………….…... 9 III. “Controversy” and Contradictions: Evaluating Prince, Past and Present……………….….. 16 IV. Cracked Actors: Homosexual Stints and Straight Realities………………………………... 23 V. “This Woman’s Work”: Female Foundations of Glam………………………………….….. 27 VI. Electric Ladies: Feminist Possibilities of Futurism and Science Fiction……………….….. 34 VII. Dirty Computer……………………………………………………………………………. 44 VIII. MASSEDUCTION………………………………………………………………………… 53 IX. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….. 60 2 Abstract Glam rock, though considered by many music critics chiefly as a historical movement, is a sensibility which is appropriated frequently in the present moment. Its original icons were overwhelmingly male—a pattern being subverted in both contemporary iterations of glam and the music industry as a whole. Fluid portrayals of gender, performative sexuality, camp, and vibrant, eye-catching visuals are among the most identifiable traits which signify the glam style, though science fiction also serves as a common thread between many glam stars, both past and present. The superficial linkages between artists like David Bowie, Prince, Janelle Monáe, and St. Vincent provide -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Luke I Wanna Rock 4:23 Luke - Greatest Hits 8 1996 Rap 128 Disk Local 2 Angie Stone No More Rain (In this Cloud) 4:42 Black Diamond 1999 Soul 3 128 Disk Local 3 Keith Sweat Merry Go Round 5:17 I'll Give All My Love to You 4 1990 RnB 128 Disk Local 4 D'Angelo Brown Sugar (Live) 10:42 Brown Sugar 1 1995 Soul 128 Disk Grand Verbalizer, What Time Is Local 5 X Clan 4:45 To the East Blackwards 2 1990 Rap 128 It? Disk Local 6 Gerald Levert Answering Service 5:25 Groove on 5 1994 RnB 128 Disk Eddie Local 7 Intimate Friends 5:54 Vintage 78 13 1998 Soul 4 128 Kendricks Disk Houston Local 8 Talk of the Town 6:58 Jazz for a Rainy Afternoon 6 1998 Jazz 3 128 Person Disk Local 9 Ice Cube X-Bitches 4:58 War & Peace, Vol.1 15 1998 Rap 128 Disk Just Because God Said It (Part Local 10 LaShun Pace 9:37 Just Because God Said It 2 1998 Gospel 128 I) Disk Local 11 Mary J Blige Love No Limit (Remix) 3:43 What's The 411- Remix 9 1992 RnB 3 128 Disk Canton Living the Dream: Live in Local 12 I M 5:23 1997 Gospel 128 Spirituals Wash Disk Whitehead Local 13 Just A Touch Of Love 5:12 Serious 7 1994 Soul 3 128 Bros Disk Local 14 Mary J Blige Reminisce 5:24 What's the 411 2 1992 RnB 128 Disk Local 15 Tony Toni Tone I Couldn't Keep It To Myself 5:10 Sons of Soul 8 1993 Soul 128 Disk Local 16 Xscape Can't Hang 3:45 Off the Hook 4 1995 RnB 3 128 Disk C&C Music Things That Make You Go Local 17 5:21 Unknown 3 1990 Rap 128 Factory Hmmm Disk Local 18 Total Sittin' At Home (Remix) -

Songs by Title

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Title www.adj2.com Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly A Dozen Roses Monica (I Got That) Boom Boom Britney Spears & Ying Yang Twins A Heady Tale Fratellis, The (I Just Wanna) Fly Sugar Ray A House Is Not A Home Luther Vandross (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra A Long Walk Jill Scott + 1 Martin Solveig & Sam White A Man Without Love Englebert Humperdinck 1 2 3 Miami Sound Machine A Matter Of Trust Billy Joel 1 2 3 4 I Love You Plain White T's A Milli Lil Wayne 1 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott A Moment Like This,zip Leona 1 Thing Amerie A Moument Like This Kelly Clarkson 10 Million People Example A Mover El Cu La Sonora Dinamita 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay, Justin Bieber A Night To Remember High School Musical 3 10,000 Nights Alphabeat A Song For Mama Boyz Ii Men 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters A Sunday Kind Of Love Reba McEntire 12 Days Of X Various A Team, The Ed Sheeran 123 Gloria Estefan A Thin Line Between Love & Hate H-Town 1234 Feist A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton 16 @ War Karina A Thousand Years Christina Perri 17 Forever Metro Station A Whole New World Zayn, Zhavia Ward 19-2000 Gorillaz ABC Jackson 5 1973 James Blunt Abc 123 Levert 1982 Randy Travis Abide With Me West Angeles Gogic 1985 Bowling For Soup About A Girl Sugababes 1999 Prince About You Now Sugababes 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The Abracadabra Steve Miller Band 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days 20 Years Ago Kenny Rogers Acapella Kelis 21 Guns Green Day According To You Orianthi 21 Questions 50 Cent Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus 21st Century Breakdown Green Day Act A Fool Ludacris 21st Century Girl Willow Smith Actos De Un Tonto Conjunto Primavera 22 Lily Allen Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes 22 Taylor Swift Adams Song Blink 182 24K Magic Bruno Mars Addicted To You Avicii 29 Palms Robert Plant Addictive Truth Hurts & Rakim 2U David Guetta Ft. -

Greatest Hits Collection Prince 4Ever Arrives on November 22 Remastered, Deluxe Version of Purple Rain Due in Early 2017

For Immediate Release NPG RECORDS & WARNER BROS. RECORDS ANNOUNCE TWO NEW PRINCE RELEASES, BOTH WITH PREVIOUSLY UNRELEASED MUSIC GREATEST HITS COLLECTION PRINCE 4EVER ARRIVES ON NOVEMBER 22 REMASTERED, DELUXE VERSION OF PURPLE RAIN DUE IN EARLY 2017 October 21, 2016 (Burbank, CA) - Today, NPG Records and Warner Bros. Records announced two new Prince releases that will celebrate the iconic artist’s music and introduce fans to previously unreleased music. This will mark the first Prince recordings released since his passing on April 21st of this year. Released on November 22nd in the U.S. and November 25th around the world, PRINCE 4Ever will bring together 40 of Prince’s best-loved songs, including the blockbuster hits “When Doves Cry,” “Let’s Go Crazy,” “Kiss,” “Little Red Corvette,” “Purple Rain,” “Raspberry Beret,” “Sign O’ The Times,” “Alphabet Street,” “Batdance,” and “Cream.” PRINCE 4Ever includes “Moonbeam Levels” - a previously unreleased song originally recorded in 1982 during the1999 sessions and later considered for the never released Rave Unto The Joy Fantastic album. PRINCE 4Ever will also arrive with a 12-page booklet of never-before-seen photos by acclaimed photographer Herb Ritts. In addition, early next year will see the release of the much-anticipated remastered, deluxe version of Purple Rain, plans for which were agreed with Prince before he passed away. The remaster of the classic Purple Rain will arrive with a second album of previously unreleased material. More details will be revealed closer to the release date. The track-listing for PRINCE 4Ever is as follows: 1. 1999 2. Little Red Corvette 3. -

LADM Admin System

Santa Clara Jan 27-29, 2017 Hyatt Regency Santa Clara 1/27/2017 Time Routine ID and Name Studio Name Age Category Division 12:00p 304 Baby I'm a Star DollHouse Dance Studio JR Jazz Solo Prep 12:03p 092 Show Off Keep In Time Dance Academy JR Musical Solo Prep Theatre 12:06p 310 Inch by Inch DollHouse Dance Studio JR Contemporary Solo 12:09p 070 You Pam Rossi's Dance Ten JR Contemporary Solo 12:12p 094 Let it Go Keep In Time Dance Academy JR Hip Hop Solo 12:15p 159 Thumbs Up Studio @-Ryan's American Dance JR Hip Hop Solo 12:18p 309 Castle DollHouse Dance Studio JR Open Solo 12:21p 459 Living in New York City RockStar Dance Studio JR Tap Duo/Trio 12:24p 595 Time Class Act Dance & Performing Arts JR Lyrical Solo Studio 12:27p 458 Dear Future Husband RockStar Dance Studio JR Open Duo/Trio 12:30p 315 Everywhere I Go DollHouse Dance Studio JR Lyrical Solo 12:33p 695 Winter Song South Bay Dance Center JR Lyrical Solo 12:36p 307 Colors of the Wind DollHouse Dance Studio JR Lyrical Solo 12:39p 502 Reflection Studio S Broadway JR Lyrical Solo 12:42p 308 Ave Maria DollHouse Dance Studio JR Lyrical Solo 12:45p 699 Childhood Dreams South Bay Dance Center JR Lyrical Solo 12:48p 700 On the Breath of an Angel South Bay Dance Center JR Lyrical Solo 12:51p 696 To Build a Home South Bay Dance Center JR Lyrical Solo 12:54p 311 One of the Boys DollHouse Dance Studio JR Musical Solo Theatre 12:57p 154 All I Need Studio @-Ryan's American Dance JR Musical Solo Theatre 1:00p 501 When Will My Life Begin? Studio S Broadway JR Musical Solo Theatre 1:03p 312 Everything's -

Read Black Magnolias Special Issue on Prince

Black Magnolias March-May, 2020 Vol. 8, No. 3 (Special Prince Issue) 1 Black Magnolias ISSN 2155-1391 Copyright 2020 Black Magnolias Black Magnolias is published quarterly by Psychedelic Literature. Subscription Rates: single issue $12.00, annual subscription $40.00. Outside the U.S. add $7.00 postage for single issue and $28.00 postage for annual subscription. All payment in U.S. dollars drawn on an U.S. bank or by International Money Order, made to Psychedelic Literature. Individual issues/copies and annual subscription orders can be purchased at www.psychedelicliterature.com/blackmagnolias.html. Postmaster: Send address changes to Black Magnolias, c/o Psychedelic Literature, 203 Lynn Lane, Clinton, MS 39056. Address all correspondence regarding editorial matters, queries, subscriptions, and advertising to [email protected], or Black Magnolias, 203 Lynn Lane, Clinton, MS 39056, or (601) 383-0024. All submissions must be sent via e-mail as a word attachment. All submissions must include a 50 - 100 word biographical note including hometown and any academic, artistic, and professional information the writer desires to share, along with the writer’s postal mailing address, e-mail address, and phone number. All rights reserved. Rights for individual selections revert to authors upon publication. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publishers. Founding Publishers Monica Taylor-McInnis C. Liegh McInnis C. Liegh McInnis, Editor Cover Art Black Magnolias XXX, 2020 Monica Taylor-McInnis Note: Cover art was originally designed by Monica Taylor-McInnis for Africology Journal, and we decided to keep it once we moved the special issue to Black Magnolias.