Planning a Good Death (BBC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number 93

O fcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 93 24 September 2007 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 93 24 September 2007 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases In Breach 4 Not in breach 12 Fairness & Privacy cases Upheld in part 14 Not Upheld 44 Other programmes not in breach/outside remit 73 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 93 24 September 2007 Introduction Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code (“the Code”) took effect on 25 July 2005 (with the exception of Rule 10.17 which came into effect on 1 July 2005). This Code is used to assess the compliance of all programmes broadcast on or after 25 July 2005. The Broadcasting Code can be found at http://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv/ifi/codes/bcode/ The Rules on the Amount and Distribution of Advertising (RADA) apply to advertising issues within Ofcom’s remit from 25 July 2005. The Rules can be found at http://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv/ifi/codes/advertising/#content From time to time adjudications relating to advertising content may appear in the Bulletin in relation to areas of advertising regulation which remain with Ofcom (including the application of statutory sanctions by Ofcom). 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 93 24 September 2007 Standards cases In Breach House of Fun 7/8 May 2007, around midnight Introduction House of Fun is a free-to-air adult entertainment channel featuring female presenters - known as “babes” – who invite viewers to call them on premium rate phone lines for sexual conversation. A complainant said the output broadcast around midnight on 7/8 May 2007 was too sexually explicit for un-encrypted transmission, particularly in a segment at 00:27. -

Lynsey De Paul

2 don’t understand why so many people are angry with the recent iTunes promotion of U2’s new album. Now, don’t get me wrong. I am not saying this because I am a fan of the band, or because I think it is a remarkable record. It’s not, and I’m not. The band have made much better records in the past, and they have made considerably worse ones. That isn’t the issue. There have been times in my life when I have been quite impressed with the band’s output, although I would never have called myself a true blue fan. But that isn’t the issue either. The issue is why are so many people incensed by the fact that iTunes paid the band an undisclosed sum (said to be in the multiple millions) to send a copy of the record to everybody who had an iTunes account on the day in question? Those beneficiaries included Dear Friends, me, by the way – twice. Welcome to another issue of Gonzo Weekly The album can be removed from your playlists magazine. For the first time in quite a few with a couple of clicks of a mouse, and although issues, our own life has quietened down I believe it is slightly more complicated if you somewhat; Weird Weekends have come and have an iPhone, I truly don’t think it is going to gone, grand-daughters have been born, and we be that much of an issue. are back in the relative safety of our own little sanctum in North Devon. -

First News Readership Gure Is 2,235,888

Working with ROYAL Issue 567 £1.80 28 April – 4 May 2017 HEADS TOGETHER by Ben Pulsford 10 YEARS OF AWARD * WINNING MORE THAN TWO MILLION READERS NEWS! * general GUARDIANS OF 18 election THE GALAXY’S MENTAL health has been a explained 7 chris pratt big topic of conversati on in the UK, over the last couple of weeks. And many people are thanking William, Catherine and Harry for starti ng this big live.fi rstnews.co.uk conversati on. SAVE EARTH With their campaign, Heads Together, the young royals have been doing everything they can to get more children, men and women opening up about mental health. They say that keeping in good CHILDREN mental health is just as important as keeping our physical health in check. Unfortunately, because we WANT LESSONS can’t always see a mental illness like a physical illness, some people feel uncomfortable talking about IN CARING FOR it. Heads Together is working hard to get everyone opening up about OUR HOME AND mental health. That conversati on has become HUGE. The charity released several ITS WILDLIFE videos that went viral, including one of Prince William FaceTiming Lady Gaga to discuss mental health, plus a very open video of William, Catherine and Harry talking about their own mental wellbeing. Conti nued on page 4 The panda is the animal children fear losing the most by editor in chief Nicky Cox SAVING the environment should be taught in schools to save the Earth, say children. The young people questioned for a new report said they were worried about Donald Trump being the President of were worried about their futures, with 87% saying they the United States. -

BBC Children in Need History

BBC Children in Need History BBC Children in Need is the BBC’s UK charity. Since 1980, it has raised more than £1 billion for disadvantaged children and young people in the UK. Their aim is to improve the lives of thousands of children by ensuring that their childhood is safe, happy and secure. They also want every child to have the chance to do their best in life. The Beginnings In 1927, the BBC broadcast its first ever appeal for children. This was a five-minute radio broadcast on Christmas Day which raised about £1143 (about the same as £27,150 nowadays) and supported four well-known children’s charities. In 1955, the first televised appeal was presented by Sooty and Harry Corbett on Christmas Day. These Christmas Day appeals continued to be broadcast on television and radio until 1979, raising more than £625,000. In November 1980, the appeal was broadcast on BBC One in a different format as a telethon, hosted by Terry Wogan, Sue Lawley and Esther Rantzen. Terry Wogan continued as the main presenter until 2014 with a variety of co- presenters, including: • Joanna Lumley; • Tess Daly; • Andi Peters; • Fearne Cotton. • Natasha Kaplinsky; Pudsey Bear Pudsey Bear first appeared in 1985. He was designed by Joanna Ball, a BBC graphic designer, who named him after the West Yorkshire town where she was born. The original Pudsey Bear had a red bandana with black triangles and a sad expression. He was very popular and returned the following year with a new bandana (white with red spots) and a more cheerful expression. -

Appendix A: Memory Myths and Realities

Appendix A: Memory Myths and Realities Myth 1. You must identify the root cause of your unhappiness from the past in order to heal and be happy in the present. Reality 1. It is unfortunately the normal human lot to be frustrated and unhappy at various points in your life. There is no magic pill to make you happy, and your attitude in the present is much more the issue than anything that happened to you in the past. Myth 2. Checklists of “symptoms” are reliable tools to identify disorders. Reality 2. Beware of symptom checklists, particularly if they apply to nearly everyone in the general population. At one time or another, most people experience depres- sion, troubled relationships, ambivalence toward family members, and low self- esteem. These are not necessarily “symptoms” of anything other than the human condition. Myth 3. You can trust any therapist who seems compassionate, warm, wise, and caring. You do not need to ask about credentials, experience, training, philosophy, treat- ment approach, or techniques. Reality 3. Just because a therapist is warm and caring does not mean that he or she is com- petent or can help you. Training, philosophy, and treatment modalities are extremely important. Therapists who dwell unceasingly on your past are unlikely to help you cope with your present-day problems. Therapy should challenge you to change your way of thinking about and dealing with the present-day conflicts that sent you to therapy in the first place. © The Author(s) 2017 421 M. Pendergrast, The Repressed Memory Epidemic, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-63375-6 422 Appendix A: Memory Myths and Realities Myth 4. -

Giving-Older-People-A-Voice-The-Case-For-An

Giving older people a voice: the case for an Older People’s Commissioner for England Edited by Paul Burstow Giving older people a voice Contributors Rt Hon Paul Burstow MP Baroness Bakewell DBE Sarah Rochira, Older People’s Commissioner for Wales Esther Rantzen CBE, Chair, The Silver Line Acknowledgements The editor is grateful to Age UK, House of Commons Library, Baroness Bakewell DBE, Sarah Rochira and the Office of the Older People’s Commissioner for Wales, Esther Rantzen CBE and The Silver Line. He would also like to thank Sean O’Brien and Natasha Kutchinsky for their support and research assistance. The editorial sections and recommendations below plus any errors are the editor’s responsibility alone. ISBN: 978-1-909274-06-8 Copyright September 2013 CentreForum All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of CentreForum, except for your own personal and non-commercial use. The moral rights of the author are asserted. 2 Giving older people a voice : Contents Foreword - Esther Rantzen CBE 4 Executive Summary 7 1. Introduction - Paul Burstow 11 2. Examining the case for an Older People’s Commissioner for England 16 3. Why the case for a commissioner grows ever more pressing - Baroness Bakewell 34 4. The role and powers of the Older People’s Commissioner for Wales - Sarah Rochira 37 5. Conclusions and recommendations 41 3 Giving older people a voice : Foreword Esther Rantzen CBE Chair, The Silver Line As a nation, we need to change our attitude to valuing and reaching out to older people. -

CHAPT Introdu 3.1 3.2 Chang 3.3 C TER 3

CHAPTER 3 – CHANGING ATTITUDES AND SEXUAL MORES Introduction 3.1 I have lost count of the number of witnesses who have told me that ‘things were different in those days’. What they were telling me is that attitudes towards sexual behaviour and, in particular, towards some of the sexual behaviour in which Savile indulged, were more tolerant in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s than the attitudes we have today. To some extent, I accept that this is so. The relevance of this is that, when I consider what staff at the BBC knew about Savile’s sexual activities and attitudes towards sex, I must judge their reactions to that knowledge in the context of the mores of the time. 3.2 In this chapter, I will provide a very brief summary of the changing attitudes in society and within the BBC on such matters as sexual mores, the position of women in society and in the workplace and child protection during the period covered by this Report. These are broad topics on which many have written extensively. I shall not attempt to summarise the published and academic work on these subjects. Instead, I shall attempt only to provide a background against which to set my examination of the BBC’s awareness of and attitudes towards Savile’s conduct and character. Changes in Sexual Mores in British Society 3.3 As Britain emerged from post-war austerity and began to enjoy the rising living standards which came with economic expansion in the late 1950s and early 1960s, there was a rapid change in social and sexual mores, particularly amongst the younger generation. -

Views on the News

Dear Supporter, Welcome to the Christmas edition of the Campaign to End Loneliness E-update! Loneliness and social isolation in older age have been mentioned frequently in newspapers and on the radio over the past few weeks. As Christmas is a time when we emphasise spending time with family and friends, it also raises awareness of those who do not have these connections. But there are many organisations and individuals who will be working hard over this festive season to try and combat loneliness. We now have a selection of Christmas case studies submitted by Campaign supporters on our website, which we hope will inspire and encourage action from all. This week Tracey Crouch spoke powerfully in the House of Commons on the issue of loneliness in older age and the work of the Campaign to End Loneliness. As she observed, this “seclusion is not confined to the Christmas season”. So as we enter 2012, the Campaign and all our supporters will continue to strive to raise awareness of, alleviate and prevent loneliness across the United Kingdom. Views on the News The Sun newspaper has been running a Christmas campaign on the theme of loneliness and social isolation. ‘Care for the Elderly this Christmas’ is asking members of the public to remember the difficulties some older people face, and volunteer or donate to look out for the elderly particularly by volunteering or donating to the charity, Friends of the Elderly. The second article on this campaign can be found here. Esther Rantzen has announced her intention to set up ‘SilverLine’, a phone line for vulnerable older people. -

Voicing the Silence: the Maternity Care Experiences of Women Who Were Sexually Abused in Childhood

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES Voicing the silence: the maternity care experiences of women who were sexually abused in childhood by Elsa Montgomery Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES Midwifery Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy VOICING THE SILENCE: THE MATERNITY CARE EXPERIENCES OF WOMEN WHO WERE SEXUALLY ABUSED IN CHILDHOOD Elsa Mary Wells Montgomery Childhood sexual abuse is a major, but hidden public health issue estimated to affect approximately 20% of females and 7% of males. As most women do not disclose to healthcare professionals, midwives may unwittingly care for women who have been sexually abused. The purpose of this study was to address the gap in our understanding of women’s maternity care experiences when they have a history of childhood sexual abuse with the aim of informing healthcare practice. -

Home Affairs Committee: Written Evidence Localised Child Grooming

Home Affairs Committee: Written evidence Localised child grooming This volume contains the written evidence accepted by the Home Affairs Committee for the Localised child grooming inquiry. No. Author Page 01 Greater Manchester Police 1 03 Jim Phillips 3 04 The End Violence Against Women Coalition 4 05 NSPCC 8 05a Supplementary 13 06 Department for Education 16 06a Supplementary 35 07 Barnardo’s 41 08 Birmingham City Council 53 09 Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre 56 10 Missing People 65 11 Home Office 79 12 Carol Hopewell 86 13 The Howard League for Penal Reform 89 14 Serious Organised Crime Agency 94 15 Esther Rantzen 97 16a Steven Walker and Samantha Roberts 102 17 The Children's Society 107 17a Supplementary 120 18 South Yorkshire Police 125 19 Safe and Sound Derby 129 20 Chris Longley MBE 133 21 The Law Society 135 22 NWG Network in Association with Victim Support 137 23 Shaun Wright, South Yorkshire Police and Crime Commissioner 140 24 Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council 144 24a Supplementary 149 As at 23 April 2013 Supplementary written evidence submitted by Sir Peter Fahy, Chief Constable, Greater Manchester Police (LCH 01) Thank you for your letter dated 20th June 2012 requesting further information following the evidence we gave to the Committee on the 12th June. In GMP we consider the following alternative methods both in terms of investigation and/or in order to disrupt offenders activity in respect of grooming and child sexual exploitation cases: 1. DNA testing of clothing of potential victims of CSE. Often deployed in relation to regular Missing From Home's who are not disclosing intelligence to form the basis of a case. -

Table of Membership Figures For

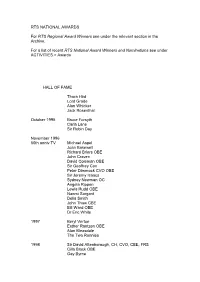

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D. -

The Dame Janet Smith Review Report

THE DAME JANET SMITH REVIEW REPORT AN INDEPENDENT REVIEW INTO THE BBC’S CULTURE AND PRACTICES DURING THE JIMMY SAVILE AND STUART HALL YEARS FOR PUBLICATION ON 25 FEBRUARY 2016 THIS REPORT CONTAINS EVIDENCE OF SEXUAL ABUSE WHICH SOME READERS MAY FIND DISTRESSING THE DAME JANET SMITH REVIEW REPORT VOLUME 1 Table of Contents CONCLUSIONS – THE QUESTIONS ANSWERED AND THE LESSONS TO BE LEARNED ...................................................................................... 1 Did Savile commit acts of inappropriate sexual conduct in connection with his work for the BBC? ................................................................ 1 Were any concerns raised within the BBC whether formally or informally about Savile’s inappropriate sexual conduct? ................................................................................................... 2 To what extent were BBC personnel aware of inappropriate sexual conduct by Savile in connection with his work for the BBC? .............................................................................................................. 7 To what extent ought BBC personnel to have been aware of inappropriate sexual conduct by Savile in connection with his work for the BBC? ................................................................................. 14 Did the culture and practices within the BBC during the years of Savile’s employment enable Savile’s inappropriate sexual conduct to continue unchecked? ............................................................ 18 The Culture of Not Complaining