COUNTERTERRORISM SPENDING: Protecting America While Promoting Efficiencies and Accountability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corpus Christi College the Pelican Record

CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LI December 2015 CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LI December 2015 i The Pelican Record Editor: Mark Whittow Design and Printing: Lynx DPM Limited Published by Corpus Christi College, Oxford 2015 Website: http://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk Email: [email protected] The editor would like to thank Rachel Pearson, Julian Reid, Sara Watson and David Wilson. Front cover: The Library, by former artist-in-residence Ceri Allen. By kind permission of Nick Thorn Back cover: Stone pelican in Durham Castle, carved during Richard Fox’s tenure as Bishop of Durham. Photograph by Peter Rhodes ii The Pelican Record CONTENTS President’s Report ................................................................................... 3 President’s Seminar: Casting the Audience Peter Nichols ............................................................................................ 11 Bishop Foxe’s Humanistic Library and the Alchemical Pelican Alexandra Marraccini ................................................................................ 17 Remembrance Day Sermon A sermon delivered by the President on 9 November 2014 ....................... 22 Corpuscle Casualties from the Second World War Harriet Fisher ............................................................................................. 27 A Postgraduate at Corpus Michael Baker ............................................................................................. 34 Law at Corpus Lucia Zedner and Liz Fisher .................................................................... -

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Woodford, I., & Smith, M. L. R. (2017). The Political Economy of the Provos: Inside the Finances of the Provisional IRA – A Revision. STUDIES IN CONFLICT AND TERRORISM. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

A Global Alliance for Open Society

INTRODUCTION A Global Alliance for Open Society The goal of the Soros foundations network throughout the world is to transform closed societies into open ones and to protect and expand the values of existing open societies. In pursuit of this mission, the Open Society Institute (OSI) and the foundations established and supported by George Soros seek to strengthen open society principles and practices against authoritarian regimes and the negative consequences of globalization. The Soros network supports efforts in civil society, education, media, public health, and human and women’s rights, as well as social, legal, and economic reform. 6 SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK | 2001 REPORT Our foundations and programs operate in more than national government aid agencies, including the 50 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, the former United States Agency for International Soviet Union, Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Development (USAID), Britain’s Department for the United States. International Development (DFID), the Swedish The Soros foundations network supports the concept International Development Cooperation Agency of open society, which, at its most fundamental level, is (SIDA), the Canadian International Development based on the recognition that people act on imperfect Agency (CIDA), the Dutch MATRA program, the knowledge and that no one is in possession of the ultimate Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation truth. In practice, an open society is characterized by the (SDC), the German Foreign Ministry, and a num- rule of law; respect for human rights, minorities, and ber of Austrian government agencies, including minority opinions; democratically elected governments; a the ministries of education and foreign affairs, market economy in which business and government are that operate bilaterally; separate; and a thriving civil society. -

The Attacks OPEN SOCIETY NEWS EDITOR’S NOTE

OPEN SOCIETY SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK NEWS WINTER | 2002 NEWS After the Attacks OPEN SOCIETY NEWS EDITOR’S NOTE WINTER 2002 SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK The September 11 terrorist attacks on America and the war in Afghanistan have prompted a host of responses from individuals, organizations, and CHAIRMAN George Soros governments around the world. For the Soros foundations network, the PRESIDENT aftermath of September 11 has had a resounding impact in areas ranging from Aryeh Neier the protection of immigrants in the United States to the promotion of human EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT Stewart J. Paperin rights in Uzbekistan. VICE PRESIDENT Deborah Harding SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR This issue of OSN examines some of the key areas of concern that have Laura Silber DEPUTY DIRECTOR emerged since September 11 to call attention to the importance of protecting James Goldston and strengthening open society values in this time of crisis. DIRECTOR OF U. S . PROGRAMS Gara LaMarche DIRECTOR OF NETWORK PROGRAMS By including materials from the “After the Attacks” section of the Soros website Elizabeth Lorant EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF OSI– BUDAPEST (www.soros.org), this issue of OSN also highlights the many ways the Soros Katalin E. Koncz network is helping the public understand the ramifications of September 11. Open Society News In addition to essays and editorials by prominent open society advocates, the EDITOR “After the Attacks” section on the web features forums and discussions with William Kramer leading policymakers, experts, and activists. It also provides information about ASSISTANT EDITOR Sarah Miller-Davenport where and how people can get help in dealing with the sadness, anger, and CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Ari Korpivaara confusion created by terrorism and war. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ ANGLO-SAUDI CULTURAL RELATIONS CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CONTEXT OF BILATERAL TIES, 1950- 2010 Alhargan, Haya Saleh Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 1 ANGLO-SAUDI CULTURAL RELATIONS: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CONTEXT OF BILATERAL TIES, 1950-2010 by Haya Saleh AlHargan Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Middle East and Mediterranean Studies Programme King’s College University of London 2015 2 ABSTRACT This study investigates Anglo-Saudi cultural relations from 1950 to 2010, with the aim of greater understanding the nature of those relations, analysing the factors affecting them and examining their role in enhancing cultural relations between the two countries. -

Wh Owat Ches the Wat Chmen

WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO I see powerful echoes of what I personally experienced as Director of NSA and CIA. I only wish I had access to this fully developed intellectual framework and the courses of action it suggests while still in government. —General Michael V. Hayden (retired) Former Director of the CIA Director of the NSA e problem of secrecy is double edged and places key institutions and values of our democracy into collision. On the one hand, our country operates under a broad consensus that secrecy is antithetical to democratic rule and can encourage a variety of political deformations. But the obvious pitfalls are not the end of the story. A long list of abuses notwithstanding, secrecy, like openness, remains an essential prerequisite of self-governance. Ross’s study is a welcome and timely addition to the small body of literature examining this important subject. —Gabriel Schoenfeld Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Author of Necessary Secrets: National Security, the Media, and the Rule of Law (W.W. Norton, May 2010). ? ? The topic of unauthorized disclosures continues to receive significant attention at the highest levels of government. In his book, Mr. Ross does an excellent job identifying the categories of harm to the intelligence community associated NI PRESS ROSS GARY with these disclosures. A detailed framework for addressing the issue is also proposed. This book is a must read for those concerned about the implications of unauthorized disclosures to U.S. national security. —William A. Parquette Foreign Denial and Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Gary Ross has pulled together in this splendid book all the raw material needed to spark a fresh discussion between the government and the media on how to function under our unique system of government in this ever-evolving information-rich environment. -

RESTORING AMERICAN LEADERSHIP Restoring American Leadership

RESTORING AMERICAN LEADERSHIP Restoring American Leadership The United States today faces a daunting array of international crises and simmering transnational problems. The current administration has committed itself to “effective multilateralism” and a world in which strong alliances play a key role in solving transnational challenges. | Cooperative Restoring American Leadership provides analysis and 13 COOPERA recommendations on 13 critical issues from international cooperation in the war on terror to curbing proliferation Steps of nuclear weapons to advancing the rights of women across the globe. Each paper offers a specific set of recommendations for action by the president consistent TIVE STEPS TO ADV with his stated values. Restoring American Leadership is to Advance Global Progress offered as a constructive contribution to the ongoing debate about how America can best assert responsible leadership in a new era. ANCE GLOBAL PROGRESS 13 Open Society Institute | Security and Peace Institute Open Society Institute | Security and Peace Institute Restoring American Leadership Cooperative Steps 13to Advance Global Progress Open Society Institute | Security and Peace Institute Copyright © 2005 by Open Society Institute and The Century Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publishers. This book is cosponsored by the Open Society Institute, a private operating and grantmaking foundation which aims to shape public policy to promote democratic governance, human rights, and economic, legal, and social reform, and by the Security and Peace Institute (SPI), a joint initiative of the Center for American Progress and The Century Foundation, which works to advance a responsible U.S. -

Black Lives Matter: Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Criminal Justice

BLACK LIVES MATTER: ELIMINATING RACIAL INEQUITY IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM For more information, contact: This report was written by Nazgol Ghandnoosh, Ph.D., Research Analyst at The Sentencing Project. The report draws on a 2014 publication The Sentencing Project of The Sentencing Project, Incorporating Racial Equity into Criminal 1705 DeSales Street NW Justice Reform. 8th Floor Washington, D.C. 20036 Cover photo by Brendan Smialowski of Getty Images showing Congressional staff during a walkout at the Capitol in December 2014. (202) 628-0871 The Sentencing Project is a national non-profit organization engaged sentencingproject.org in research and advocacy on criminal justice issues. Our work is twitter.com/sentencingproj supported by many individual donors and contributions from the facebook.com/thesentencingproject following: Atlantic Philanthropies Morton K. and Jane Blaustein Foundation craigslist Charitable Fund Ford Foundation Bernard F. and Alva B. Gimbel Foundation General Board of Global Ministries of the United Methodist Church JK Irwin Foundation Open Society Foundations Overbrook Foundation Public Welfare Foundation Rail Down Charitable Trust David Rockefeller Fund Elizabeth B. and Arthur E. Roswell Foundation Tikva Grassroots Empowerment Fund of Tides Foundation Wallace Global Fund Working Assets/CREDO Copyright © 2015 by The Sentencing Project. Reproduction of this document in full or in part, and in print or electronic format, only by permission of The Sentencing Project. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 I. Uneven Policing in Ferguson and New York City 6 II. A Cascade of Racial Disparities Throughout the Criminal Justice System 10 III. Causes of Disparities 13 A. Differential crime rates 13 B. Four key sources of unwarranted racial disparities in criminal justice outcomes 15 IV. -

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia Michael Krepon, Rodney W. Jones, and Ziad Haider, editors Copyright © 2004 The Henry L. Stimson Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Henry L. Stimson Center. Cover design by Design Army. ISBN 0-9747255-8-7 The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street NW Twelfth Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations..................................................................................................... vii Introduction......................................................................................................... ix 1. The Stability-Instability Paradox, Misperception, and Escalation Control in South Asia Michael Krepon ............................................................................................ 1 2. Nuclear Stability and Escalation Control in South Asia: Structural Factors Rodney W. Jones......................................................................................... 25 3. India’s Escalation-Resistant Nuclear Posture Rajesh M. Basrur ........................................................................................ 56 4. Nuclear Signaling, Missiles, and Escalation Control in South Asia Feroz Hassan Khan ................................................................................... -

June 10, 2021 Hearing Transcript

HEARING ON CHINA’S NUCLEAR FORCES HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION THURSDAY, JUNE 10, 2021 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2021 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, CHAIRMAN ROBIN CLEVELAND, VICE CHAIRMAN Commissioners: BOB BOROCHOFF DEREK SCISSORS JEFFREY FIEDLER HON. JAMES M. TALENT KIMBERLY GLAS ALEX N. WONG HON. CARTE P. GOODWIN MICHAEL R. WESSEL ROY D. KAMPHAUSEN The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 106–398 (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002), as amended by: The Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act, 2002, Pub. L. No. 107–67 (Nov. 12, 2001) (regarding employment status of staff and changing annual report due date from March to June); The Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003, Pub. L. No. 108–7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); The Science, State, Justice, Commerce, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2006, Pub. L. No. 109–108 (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of the Commission and applicability of FACA); The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008, Pub. L. No. 110–161 (Dec. 26, 2007) (regarding submission of accounting reports; printing and binding; compensation for the executive director; changing annual report due date from June to December; and travel by members of the Commission and its staff); The Carl Levin and Howard P. -

Contributors

Contributors Ralph A. Cossa is Executive Director of the Pacific Forum CSIS in Honolulu, a non-profit, foreign policy research institute affiliated with the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. He is also a board member of the Council on US–Korean Security Studies and an Overseas Honorary Research Fellow with the Korea Institute for Defense Analysis. Cossa is a founding member of the Steering Committee of the multinational Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP), a nongovernmental organization focusing on regional confidence building and multilateral security cooperation, and also serves as Executive Director of the US Committee (USCSCAP). He also co-chairs the international CSCAP working group on confidence and security building measures. Richard E. Darilek is a senior staff member of the RAND Corporation in Washington, D.C. He is also project director for Korean and Middle East Arms Control studies. From August 1989–March 1991, he served as Distinguished Visiting Analyst at the US Army’s Concepts Analysis Agency (CAA) in Bethesda, Maryland. Previously, he has worked at the Council on Foreign Relations, the International Institute for Strategic Studies (London), and the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Darilek is the author of A Loyal Opposition in time of War: The Republican Party and the Politics of Foreign Policy from Pearl Harbor to Yalta (1976), various RAND studies, and numerous publications on US foreign and defense policy issues. He holds a Ph.D. and an M.A. in History from Princeton University. Sony Devabhaktuni is Program Assistant for South Asia at the Asia Society in New York City. -

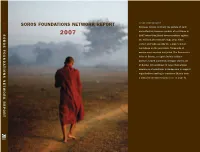

Soros Foundations Network Report

2 0 0 7 OSI MISSION SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT C O V E R P H O T O G R A P H Y Burmese monks, normally the picture of calm The Open Society Institute works to build vibrant and reflection, became symbols of resistance in and tolerant democracies whose governments SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT 2007 2007 when they joined demonstrations against are accountable to their citizens. To achieve its the military government’s huge price hikes mission, OSI seeks to shape public policies that on fuel and subsequently the regime’s violent assure greater fairness in political, legal, and crackdown on the protestors. Thousands of economic systems and safeguard fundamental monks were arrested and jailed. The Democratic rights. On a local level, OSI implements a range Voice of Burma, an Open Society Institute of initiatives to advance justice, education, grantee, helped journalists smuggle stories out public health, and independent media. At the of Burma. OSI continues to raise international same time, OSI builds alliances across borders awareness of conditions in Burma and to support and continents on issues such as corruption organizations seeking to transform Burma from and freedom of information. OSI places a high a closed to an open society. more on page 91 priority on protecting and improving the lives of marginalized people and communities. more on page 143 www.soros.org SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT 2007 Promoting vibrant and tolerant democracies whose governments are accountable to their citizens ABOUT THIS REPORT The Open Society Institute and the Soros foundations network spent approximately $440,000,000 in 2007 on improving policy and helping people to live in open, democratic societies.