July-Sept 2015 Pdf.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arj-Oano. 836-2019

MAHARASHTRA ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL MUMBAI BENCH AT AURANGABAD ORIGINAL APPLICATION NO. 836 OF 2019 DIST. : DHULE Sajidbanu Gulamnabi Shahpure, ) Age. 47 years, Occu. Service, ) as Executive Engineer, Dhule Irrigation ) Division, Dhule, ) R/o P.W.D. Class I Quarter 1/6, ) Room No. 3, Oppo. Zilla Parishad, ) Dhule, Dist. Dhule. )-- APPLICANT V E R S U S 1. The State of Maharashtra, ) Through its Principal Secretary, ) Water Resources Department, ) M.S., Mantralaya, Mumbai - 32. ) 2. The Chief Engineer, ) Tapi Irrigation Development ) Corporation, Jalgaon, ) Sinchan Bhavan, ) Akashwani Chowk, Jalgaon – 01. ) 3. The Superintending Engineer, ) Command Area Development ) Authority, Jalgaon, ) Girana Bhavan, Opp. Akashwani, ) Jalgaon – 425 001. ) -- RESPONDENTS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ APPEARANCE :- Shri A.S. Deshmukh, learned Advocate for the applicant. : Shri M.S. Mahajan, learned Chief Presenting Officer for the respondent no. 1. : Smt. Suchita A. Dhongde, learned Advocate holding for Shri S.D. Dhongde, learned Advocate for respondent nos. 2 & 3. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ CORAM : Hon’ble Shri B.P. Patil, Vice Chairman RESERVED ON : 23.6.2020 PRONOUNCED ON : 30.6.2020 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 O.A. NO. 836/19 O R D E R 1. The applicant has challenged the order dated 17.9.2019 passed by the respondent no. 1 the Principal Secretary, Water Resources Department, Mantralaya, Mumbai thereby transferring her from the post of Executive Engineer, Dhule Irrigation Division, Dhule to the post of Executive Engineer, Canal Design Division No. 2, Nashik, by filing the present O.A. 2. The applicant has passed B.E. (Civil) in the year 1994. On 18.1.1999 she entered in the Government service as a Junior Engineer. On 24.1.2001 she was appointed as a Assistant Engineer, Grade-II in the Public Works Department. -

July-Sept 2015 Pdf.Cdr

CHAPTER -V 5.1 PresentJEconomic Status of Kokana Tribes. a) Age b) Language 86 Religion c) Family Type. d) Formal 85 Non-formal (Special) Social status of the Respondents. e) Social background of family Members. f) Sources of Income 5.2 Present Trend of Education among the Kokana Tribe. a) Present Educational Condition of Children Between the age of 6 -12 years. b) Reasons for not attending the school c) Relationship of Education with Socio-Economic Status of the Respondents. 5.3 Motivational and Attitudinal Responses of the concerned people. a) Expected level of education by parents and students. b) Attitude of Household and Student Respondent towards Education and future career. c) Expected place for Education and future living. d) Opinion of Household Respondents in terms of study of children and working village school. e) Forms of motivating children for education. f) Attitude of students towards education. g) Motivation among the students for education. h) Difficulties faced by students Respondents in studying in various subjects. i) Reasons of facing difficulties in studying various subjects. j) Opinion of Teachers on the need for having special training for tribal education. k) Languages used by Teachers in teaching /communicating with Tribal Children. 1) Teachers perception regarding attitude of tribal parents towards school, functioning of schools and education. 5.1 PRESENT SOCIO- ECONOMIC STATUS OF KOKANA TRIBE The data analyzed and presented in the chapter was collected mainly through three types of units in order to project the picture of socio-economic condition of Kokana Tribe. These units consisted of 360 respondents. I.e. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Office Address Permanent Address S. G. Patil Arts, Sci & Comm VIJAY BHAIDAS College, BACHCHHAV Sakri, 46,SUSHILA NAGAR SAKRI - Dist : Dhulia. 424304 Dist : DHULE Tal : Pin - 424304 (MS.) SAKRI Maharashtra Personal Details Name VIJAY BHAIDAS BACHCHHAV Date of Birth 1 st Jun. 1961 Nationality Indian Marital status Married Category Open Present Post Associate Professor and Head, Deptt. Of English Date of Appointment 08/08/1988 Scale of Pay and Present AGP- 9000/- Pay 46,SUSHILA NAGAR SAKRI - 424304 Dist : DHULE Tal : Present Address SAKRI. Maharashtra Mobile No. +91-9423942851 E-Mail [email protected] Teaching Experience 25 years (U.G.) Research Experience 10 years Languages Known Marathi, Hindi, and English Educational Qualification Exam. Name of The University Year of Class Subject Passed Passing B. A University of Pune, Pune 1986 First English M. A University of Pune, Pune 1988 Second English P.G.D.T.E CIEFL, Hyderabad 1993 B English grade Ph.D. North Maharashtra Univ., Jalgaon Registration - ELT in- Feb2011 MS-CIT M.S.B.T.E., Mumbai Dec. 2004 First I.T. Orientation and Refresher courses attended Sr. No. Name of the A.S.College Duration 1 A.S.C.Devi Ahjilya Vishwavidyalaya Indore 2 Pratap College Amalner 7 to 27/3/1991 3 A.S.C. University of Pune, Pune 6/9 to 3/10/1994 4 A.S.C. Saurashtra University Rajkot 8/5 to 1/6/1996 Ph.D.Research Topic ACHIEVEMENT IN ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE: AN IINVESTIGATION OF ERRORS COMMIITED BY THE UNDERGRADUATE TRIBAL AND NON- TRIBAL STUDENTS IN THE COLLEGES OF DHULIA AND NANDURBAR DISTRICT: IN NORTH MAHARASHTRA REGION: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC STUDY Guide - Dr. -

2020090269.Pdf

INDEX Sr. No. Description Page No. Part I:District Survey Report for Sand Mining Or River Bed Mining 1. Introduction 8 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District 8 3. The list of Mining Leases in the district with the location and period of Validity 10 4. Details of royalty or revenue received in last three year 11 5. Details Of Production Of Sand Or Bajri Or Minor Mineral In Last Three Years 11 6. Recommendation of Enforcement & Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining by 11 MoEF&CC- 2020: 7. Process Of Deposition Of Sediments In The Rivers Of The District 16 8. General profile of the district 24 9. Land Utilization Pattern Of The District 26 10. Physiography Of The District 27 11. Rainfall Data Of The District 28 12. Geology Of The District 29 Part II: for Other Minor Minerals other than sand 1 Introduction 39 2 Overview of mining activity in the district 39 3 General Profile of district 41 4 Geology of District 44 5 Drainage of Irrigation pattern; 45 6 Land Utilization Pattern in the District: Forest, Agricultural, Horticultural, Mining 45 etc. 7 Surface Water and Ground Water scenario of the district 47 8 Rainfall of the district and climatic condition 48 9 Details of the mining leases in the District as per the format 49 10 Details of Royalty or Revenue received in last three years 50 11 Details of Production of Minor Mineral in last three years 50 12 Mineral Map of the District 51 13 List of Letter of Intent (LOI) Holders in the District along with its validity as per 51 the format 14 Total Mineral Reserve available in the District 52 15 Quality /Grade of Mineral available in the District 52 16 Use of Mineral 52 17 Demand and Supply of the Mineral in the last three years 52 18 Mining leases marked on the map of the district 52 19 Details of the area of where there is a cluster of mining leases viz. -

District Census Handbook, Dhulia

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK DHULIA Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS OFFICE BOMBAY Printed in India by the IV[anager, Gm-enullent Press and Book Depot, Nagpur, and Published by the Director, Government Printing and Stationery, .l\faharashtra State, BombaY-4. 1965 [Price-Rs. Eight] .L J ~ 'f T Q II a. J. S 0, g I !1 <So \> ~.,. o )lI,. '1-._ • ... ". ,,.;> I. , J. 'L ,---------- CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 Central Government Publications Census Report, Volume X-Maharashtra, is published in the following Parts I-A and B General Report I-C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables II-B (i) General Economic Tables-Industrial Classification II-B (ii) General Economic Tables-Occupational Classification II-C (i) Social and Cultural Tables II-C (ii) Migration Tables III Household Economic Tables IV Report on Housing and Establishments V-A Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in IVIaharashtra-Tables V-B Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in Maharashtra-Et.\lnographic ~~ . VI (1-35) Village Surveys (35 monographs on 35 selected villages) VII-A Handicrafts in Maharashtra VII-B Fairs and Festivals in Maharashtra VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration (For official use only) VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation (For official use only) IX Census Atlas of Maharashtra X (1-12) Cities of l\1aharashtra (15 Volumes-Four volumes on Greater Bombay and One each on other eleven Cities) State Government Publications 25 Volumes of District Census Handbooks in English 25 Volumes of District Census Handbooks in Marathi Alphabetical List of Villages in Maharashtra J -856-i-b (Dhulia) PREFACE On the suggestion of the Census Commissioner, India, the Government of lVlaharashtra decided to publish the District Census Handbooks on the basis of the material collected during the 1961 Census for all the districts in Maharashtra. -

18 Annual Report 2007-2008

NORTH MAHARASHTRA UNIVERSITY || ÓÖ¸üß ¯Öêü¾Öæ ÖÖÖµÖÖêÖ || ANNUAL REPORT 2007 - 08 North Maharashtra University Post Box No. 80, Umavinagar, Jalgaon - 425 001. Telegraphic Address : 'UTTAMVIDYA'. Telephone Nos. : 2257100, 2258428 - 2258429. Fax No. : 0257-2258403. E-mail : [email protected] Website : http ://www.nmu.ac.in EIGHTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT - 2007-2008 NORTH MAHARASHTRA UNIVERSITY ×¾ÖªÖ¯Ößü ÖßÖ EIGHTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT - 2007-2008 NORTH MAHARASHTRA UNIVERSITY MISSION OF THE UNIVERSITY To impart relevant quality higher education to the students, to groom them to be conscious researchers, technologists, professionals and citizens, bearing the torch for disseminating knowledge in masses for sustainable socio-economic development of the society. EIGHTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT - 2007-2008 NORTH MAHARASHTRA UNIVERSITY PUBLICATION COMMITTEE (1) DR. P. R. CHAUDHARI CHAIRMAN (2) DR. M.V. BARIDE MEMBER (3) DR. M. S. KHARATE MEMBER (4) MR. B. P. SAVAKHEDKAR MEMBER (5) DR. K. M. PATIL MEMBER (6) DR. M. V. KULKARNI MEMBER (upto 30/05/2008) (7) DR.MRS. R.S. BENDRE MEMBER (8) DR. R.B. CHINCHOLKAR CO-ORDINATOR Published by : Registrar, North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon. Matter Compilation, Photographs : Public Relations Office Designed by Composing & Setting by : D.T. P. Unit, Registrar Office NORTH MAHARASHTRA UNIVERSITY, JALGAON EIGHTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT - 2007-2008 NORTH MAHARASHTRA UNIVERSITY P R E F A C E With great pleasure, we are submitting the Eighteenth Annual Report of the North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon to the Senate. This report has been prepared under the directions of the Management Council in compliance with Section 104 of the Maharashtra Universities Act, 1994. It highlights facts and figures relating to qualitative and quantitative progress of the University during the academic year; July, 2007 to June, 2008. -

Comparative Study of Wenner and Schlumberger Electrical Resistivity Method for Groundwater Investigation: a Case Study from Dhule District (M.S.), India

Appl Water Sci DOI 10.1007/s13201-017-0576-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Comparative study of Wenner and Schlumberger electrical resistivity method for groundwater investigation: a case study from Dhule district (M.S.), India 1 1 1 Baride Mukund Vasantrao • Patil Jitendra Bhaskarrao • Baride Aarti Mukund • 2 3 Golekar Rushikesh Baburao • Patil Sanjaykumar Narayan Received: 6 December 2016 / Accepted: 18 May 2017 Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract The area chosen for the present study is Dhule resistivity and thickness for Wenner method. Regionwise district, which belongs to the drought prone area of curves were prepared based on resistivity layers for Sch- Maharashtra State, India. Dhule district suffers from water lumberger method. Comparing the two methods, it is problem, and therefore, there is no extra water available to observed that Wenner and Schlumberger methods have supply for the agricultural and industrial growth. To merits or demerits. Considering merits and demerits from understand the lithological characters in terms of its hydro- the field point of view, it is suggested that Wenner inverse geological conditions, it is necessary to understand the slope method is more handy for calculation and interpre- geology of the area. It is now established fact that the tation, but requires lateral length which is a constrain. geophysical method gives a better information of subsur- Similarly, Schlumberger method is easy in application but face geology. Geophysical electrical surveys with four unwieldy for their interpretation. The work amply proves electrodes configuration, i.e., Wenner and Schlumberger the applicability of geophysical techniques in the water method, were carried out at the same selected sites to resource evaluation procedure. -

PREFACE: Karm

SELF STUDY REPORT 2015 PREFACE: Karm. A. M. Patil Arts, Commerce & Kai. Annasaheb N. K. Patil Science Sr. College Pimpalner, Tehasil Sakri, Dist. Dhule is governed by Pimpalner Education Society. The college was established in June 1983 with commerce faculty & from 1985 Arts & Science faculties for providing educational facility to the undergraduate level to the masses who were economically backward and socially downtrodden, particularly tribal peoples from western zone of Sakri Tehasil. More than 85% tribal people live in this area which is far away from the main stream of the society. Previously there were no facilities for higher education to the students of this region and they had to go to Sakri or Dhule district for higher education, which was not at all feasible and affordable for common man. In such situation the college was started by a great social worker form this region Karm. Bapusaheb Anandrao Manikrao Patil, Kai. Annasaheb N. K. Patil and Kai. Dadasaheb V. K. Wani to fulfil the basic need of society. Our co-educational college was started in the humble way. By facing various difficulties, this college now becomes one of the leading college in our District. The credit goes to the management, students, teaching and non-teaching staff. The college is affiliated to North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon and conducts undergraduate programmes for Arts, Science and Commerce. The library is well furnished with reading hall and internet facility. It has sufficient books, encyclopedias, reference books, textbooks, periodicals, journals and daily newspapers. The college has Gymkhana department which provides outdoor game facilities to the students for inter-college, Zonal and University level sport competitions. -

Vigyan Ashram Status Report

Vigyan Ashram Status Report Volume 25 Issue 1 January 2007 In this issue… • Beginning of Silver Jubilee year of Vigyan ashram • Life skill training program under Sarva shiksha Abhiyan • Screening of Documentary at various places • Launch of Gubal project Vigyan Ashram enters into Silver Jubilee year Dr.Kalbag started Vigyan Ashram on 1st Jan 1983 on this barren hill at Pabal. We completed 24years on 1st Jan 07 and this is our Silver Jubilee year. On this occasion, We would like to congratulate our supporters, students, funding agencies, Indian Institute Of Education for their support. We are planning following programs to celebrate our silver jubilee. 1) Association of our alumni and their get together 2) Release of book on articles written by Dr.Kalbag 3) We are also targeting to 100 schools in our IBT network. Life skill training program under SSA Sangali, Kolhapur and Pune Zillha Parishad decided to implement our program in five schools each for 5th – 7th std. We conducted following training program for their instructors. 1) Training for five Schools in Sangli Dist. at Palus on 3rd and 4th Jan. {20 instructors, 5 teachers, 5 Principal } 2) Training for five schools in Kolhapur Dist. at Dewale on 11th and 12th Jan. { 20 instructors, 5 teachers, 5 Principal } 3) Training for five schools in Chakan Dist.Pune at Chakan on 19th and 20th Jan { 20 instructors, 5 teachers, 5 Principal } We also conducted training program for 171 schools at the request of Kolhapur Z.P On 22nd & 23rd Jan. Screening of documentary Mr.Sameer Shipurkar organized screening of new documentary on ‘Vigyan Ashram’ at various places. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Office Address Permanent Address Associate- Professor, Saraansh”16, sushila Nagar, Department of Zoology, V. Sakri, Dist. Dhulia V. M’s S. G. Patil Arts, Pin - 424304 (MS) Science & Commerce Email: [email protected] College, Sakri, Dist : Dhulia. Email: [email protected] Pin - 424304 (M.S.). Mobile: +91-9421885464, Phone: 02568242323 +91-9766804023. Phone: 02568240355. Personal Details Name DR. SHATRUGHNA SUKDEO PATOLE Date of Birth 1st May 1963. Nationality Indian Marital status Married Category S. C. Present Post Associate Professor, Department of Zoology. Date of Appointment 27/07/1987. Scale of Pay and Present Pay AGP- 9000/- 16, “Saraansh” SushilaNagar, Sakri, Present Address Dist. Dhulia 424304 (MS) Mobile No. +91-9421885464 E-Mail [email protected] Teaching Experience 26 years (U.G.) Research Experience 20 years Languages Known Marathi, Hindi, and English. 1 Educational Qualification Exam. Name of The University Year of Class Subject Passed Passing B. Sc. University of Pune, Pune April 1985 Distinc Zoology M. Sc. University of Pune, Pune April 1987 First Zoology M.Phil. North Maharashtra Univ., Jalgaon. Oct 1995 A grade Zoology Ph.D. North Maharashtra Univ., Jalgaon. Aug 2007 -- Zoology C. C. C. O M.S.B.T.E., Mumbai 1999 First computer M. Phil/ Ph.D. Research Topic M. Phil: Dissertation title “Studies on fish toxicants of plant origin”. Ph. D. Thesis title “Evaluation of indigenous plants for their biological activities with special reference to insecticides” Guide: Dr. R. T. Mahajan, HOD, Zoology Department, M. J. College, Jalgaon. Orientation and Refresher courses attended Sr. No. Name of the A. S. College Duration 1 Academic Staff College University of Pune. -

JAIIB | CAIIB | RRB NTPC | SSC and State Government 1 Jobs Ambitiousbaba.Com Online Test Series

ambitiousbaba.com Online Test Series Best Online Test Series Site for Bank | JAIIB | CAIIB | RRB NTPC | SSC and State Government 1 Jobs ambitiousbaba.com Online Test Series PARA 13.2 GA CAPSULE (Covered MARCH to AUGUST 2021) Index No. of Chapter Topics Name Page No. Chapter 1 Important Appointment (National, International) 4-21 Chapter 2 Awards (National, International) 22-51 Chapter 3 Government Scheme/ campaign 51-57 Chapter 4 Summit/ Conference 57-61 Chapter 5 Ranking Index 61-69 Chapter 6 Partnership/ Agreement 69-77 Chapter 7 loans agreement for India from different 77-80 organizations Chapter 8 Mergers and Acquires 80-82 Chapter 9 APP/Website/Card 82-85 Chapter 10 India’s GDP Forecast FY21 &22 (Last Update 12th 85-86 Jan 2021) Chapter 11 Budget 2020 & Atma Nirbhar Package 86-94 Chapter 12 Important Committee 94-97 Chapter 13 Banking & Financial 98-117 Chapter 14 Current Affairs (National) In Short 117-133 Chapter 15 Current Affairs (International) In Short 133-138 Chapter 16 Defence News 138-149 Chapter 17 Sports News 149-162 Chapter 18 Upcoming Sports Events & Venues 162-164 Chapter 19 List of Important Book and Author 2020 164-166 Chapter 20 Important Day and Theme 2020 166-184 Best Online Test Series Site for Bank | JAIIB | CAIIB | RRB NTPC | SSC and State Government 2 Jobs ambitiousbaba.com Online Test Series Chapter 21 Obituary 184-188 Chapter 22 Science related News 188-190 Chapter 23 Banks Name & CEO of Bank & Headquarter & 190-193 Tagline Chapter 24 State Chief Ministers and Governors 193-195 Chapter 25 Cabinet ministers of India with their constituency 195-200 Chapter 26 List of Union Ministry Secretary 200-201 Static No. -

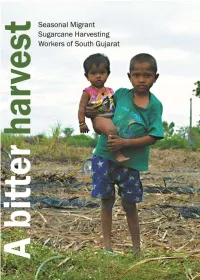

Studies Surat for Providing Critical Inputs in Design and Writing of the Study and Hosting Two Consultations Related to the Study

Acknowledgements The report was researched and published by Prayas Centre for Labor Research and Action (PCLRA). It was sponsored by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation e.v. with funds of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of the Federal Republic of Germany. We thank Centre for Social Studies Surat for providing critical inputs in design and writing of the study and hosting two consultations related to the study. PCLRA would like to thank the workers who participated in the study. Research team Prof. Kiran Desai Sudhir Katiyar Video and photography Denis Macwan Data collection Shanti Lal Meena Denis Macwan Amar Nath Sanjay Dayal Thakor Balwant Singh Dinesh Parmar Editing Dhruv Sharma Design Pollencomm Printed at .................... A Bitter Harvest Seasonal Migrant Sugarcane Harvesting Workers of South Gujarat Findings of a Research Study December 2017 Study undertaken by Prayas through its designated unit Centre for Labour Research and Action Sponsored by Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung PrayasCentre for Labour Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Research and Action (PCLRA) FORWARD Sugarcane is the money spinning crop which has much added to the wealth of the main landowners in south Gujarat. The cutting of this crop is known as ‘the campaign’ and lasts for four to five months in between November and May. A huge labour army is annually recruited already for more than half a century by the management of mills set up and owned by co-operatives to harvest the cane which is cultivated in the fields of the farmers who are members and owners of these enterprises. “The crushing of cane and of labour” was how I wrote up my findings of the anthropological fieldwork in and around Bardoli.