The Capitol Commission; Involvement of the Olmsted Brothers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The LDS Church and Public Engagement

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Asbury Theological Seminary The LDS Church and Public Engagement: Polemics, Marginalization, Accomodation, and Transformation Dr. Roland E. Bartholomew DOI: 10.7252/Paper. 0000 44 | The LDS Church and Public Engagement: Te history of the public engagement of Te Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as the “Mormons”) is a study of their political, social, and theological shift from polemics, with the associated religious persecution and marginalization, to adjustments and accommodations that have rendered periods of dramatically favorable results. In two generations Mormonism went from being the “ultimate outcast”—its members being literally driven from the borders of the U.S. and persecuted abroad—to becoming the “embodiment of the mainstream” with members fguring prominently in government and business circles nationally and internationally; what one noted journalist has deemed “a breathtaking transformation.”1 I will argue that necessary accommodations made in Church orthodoxy and orthopraxy were not only behind the political, social, and theological “mainstream,” but also consistently outlasted their “acceptability,” as the rapidly changing world’s values outpaced these changes in Mormonism. 1830-1889: MARGINALIZATION Te frst known public engagement regarding Mormonism was when the young Joseph Smith related details regarding what has become known as his 1820 “First Vision” of the Father and the Son. He would later report that “my telling the story had excited a great deal of prejudice against me among professors of religion, and was the cause of great persecution.”2 It may seem strange that Joseph Smith should be so criticized when, in the intense revivalistic atmosphere of the time, many people claimed to have received personal spiritual manifestations, including visions. -

The Mormons Are Coming- the LDS Church's

102 Mormon Historical Studies Nauvoo, Johann Schroder, oil on tin, 1859. Esplin: The Mormons are Coming 103 The Mormons Are Coming: The LDS Church’s Twentieth Century Return to Nauvoo Scott C. Esplin Traveling along Illinois’ scenic Highway 96, the modern visitor to Nauvoo steps back in time. Horse-drawn carriages pass a bustling blacksmith shop and brick furnace. Tourists stroll through manicured gardens, venturing into open doorways where missionary guides recreate life in a religious city on a bend in the Mississippi River during the mid-1840s. The picture is one of prosper- ity, presided over by a stately temple monument on a bluff overlooking the community. Within minutes, if they didn’t know it already, visitors to the area quickly learn about the Latter-day Saint founding of the City of Joseph. While portraying an image of peace, students of the history of Nauvoo know a different tale, however. Unlike other historically recreated villages across the country, this one has a dark past. For the most part, the homes, and most important the temple itself, did not peacefully pass from builder to pres- ent occupant, patiently awaiting renovation and restoration. Rather, they lay abandoned, persisting only in the memory of a people who left them in search of safety in a high mountain desert more than thirteen hundred miles away. Firmly established in the tops of the mountains, their posterity returned more than a century later to create a monument to their ancestral roots. Much of the present-day religious, political, economic, and social power of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traces its roots to Nauvoo, Illinois. -

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

Editor's Introduction: in the Land of the Lotus-Eaters

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 10 Number 1 Article 2 1998 Editor's Introduction: In the Land of the Lotus-Eaters Daniel C. Peterson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Peterson, Daniel C. (1998) "Editor's Introduction: In the Land of the Lotus-Eaters," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 10 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol10/iss1/2 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Editor’s Introduction: In the Land of the Lotus-Eaters Author(s) Daniel C. Peterson Reference FARMS Review of Books 10/1 (1998): v–xxvi. ISSN 1099-9450 (print), 2168-3123 (online) Abstract Introduction to the current issue, including editor’s picks. Peterson explores the world of anti-Mormon writing and fiction. Editor's Introduction: In the Land of the Lotus-Eaters Daniel C. Peterson We are the persecuted children of God-the chosen of the Angel Merona .... We are of those who believe in those sacred writings, drawn in Egyptian letters on plates of beaten gold, which were handed unto the holy Joseph Smith at Palmyra. - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarletl For years, I have marveled at the luxuriant, even rank, growth that is anti-Mormonism. -

The Lot Smith Cavalry Company: Utah Goes to War

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2013-10 The Lot Smith Cavalry Company: Utah Goes to War Joseph R. Stuart Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Kenneth L. Alford Ph.D. Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Stuart, Joseph R. and Alford, Kenneth L. Ph.D., "The Lot Smith Cavalry Company: Utah Goes to War" (2013). Faculty Publications. 1645. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1645 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Erected on the grounds of the Utah State Capitol by the Daughters of Utah Pioneers in 1961, this monument honors the men who served in the Lot Smith Utah Cavalry. (Courtesy of W. Jeffrey Marsh) CHAPTER 8 Joseph R. Stuart and Kenneth L. Alford THE LOT SMITH CAVA L RY C OM PANY Utah Goes to War hen the American Civil War is studied, a time.2 Indian attacks on mail and telegraph Wit is almost always the major battles and stations left the nation without cross-country campaigns that draw our attention and focus communication, threatening further confu- our interest—Manassas, Chancellorsville, Fred- sion on both sides of the country.3 ericksburg, Antietam, Gettysburg, and many Given geographic realities and Washing- others. In remembering a war that cost hun- ton’s attitude, Utah’s active participation in dreds of thousands of lives, it is often easy to the Civil War was limited. -

Printable Bike

c ycle The ciTy c ycle The ciTy DeStInAtIonS DeStInAtIonS CYCLE THE About the Route: Cycle the City is suit- SLC Main Library: An able for bicyclists who are generally comfortable riding 7 architectural gem designed by on urban streets with bike lanes. the route mostly uses world-renowned architecture firm bike lanes and paths, on fairly flat terrain, with one long, Moshe Safdie and Associates, the CITY gradual hill up lower City Creek Canyon. Library has five floors and over a half-million books. Shops on the Pioneer Park: t he starting point to our route, main floor offer a variety of services, 1 Pioneer Park is the former site of the old Pioneer Fort, such as food, coffee, artwork and a florist. erected the week the first Mormon pioneers arrived in Salt Lake in 1847. today it is home to the twilight t he Leonardo: t his contem- Concert Series, Saturday Farmers’ Market, and many 8 porary museum of art, science and more community activities. technology is named after Leonardo DaVinci. the Leonardo features Temple Square: Situated in one-of-a-kind interactive exhibits, 2 the heart of downtown, temple Square programs, workshops and classes. features the temple, exquisite gardens, tabernacle, and the world headquar- Liberty Park: A classic urban ters of the Church of Jesus Christ of 9 park with a central tree-lined prome- Latter-day Saints. Please dismount and nade, Liberty Park features a walk- walk your bicycle through the Square. ing/biking loop path that you will sample on this ride. Memory Grove: this beauti- t racy Aviary: Located in a tranquil, wooded 3 ful park features several memorials to utah’s veterans, a replica of the 10 setting within Liberty Park, the Aviary is one of the Liberty bell, and hiking trails through a largest in the country: home to over 100 species of botanical garden. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996

Journal of Mormon History Volume 22 Issue 1 Article 1 1996 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1996) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol22/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --The Emergence of Mormon Power since 1945 Mario S. De Pillis, 1 TANNER LECTURE • --The Mormon Nation and the American Empire D. W. Meinig, 33 • --Labor and the Construction of the Logan Temple, 1877-84 Noel A. Carmack, 52 • --From Men to Boys: LDS Aaronic Priesthood Offices, 1829-1996 William G. Hartley, 80 • --Ernest L. Wilkinson and the Office of Church Commissioner of Education Gary James Bergera, 137 • --Fanny Alger Smith Custer: Mormonism's First Plural Wife? Todd Compton, 174 REVIEWS --James B. Allen, Jessie L. Embry, Kahlile B. Mehr. Hearts Turned to the Fathers: A History of the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1894-1994 Raymonds. Wright, 208 --S. Kent Brown, Donald Q. Cannon, Richard H.Jackson, eds. Historical Atlas of Mormonism Lowell C. "Ben"Bennion, 212 --Spencer J. Palmer and Shirley H. -

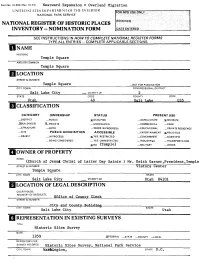

Temple Square AND/OR COMMON Temple Square [LOCATION

Form NO. 10-300 (Rev io-74) Westward Expansion - Overland Migration UNITED STAThS DEPARTMENT OF THH INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Temple Square AND/OR COMMON Temple Square [LOCATION STREETS NUMBER Temple Square _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Salt Lake City _. VICINITY OF 2 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Utah. 49 Salt Lake 035 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM JSBUILDING(S) X_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE — ENTERTAINMENT X-REL'GIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X.NO (Temple) —MILITARY _ OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME (.Church, of Jesui Christ of Latter Day Saints ) Mr. Keith Garner,President,Temple STREETS NUMBER Vistors Center Temple Square CITY. TOWN STATE Salt Lake City _ VICINITY OF Utah 84101 HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Office*j- £J of,- County„ Clerk^11 STREET & NUMBER .... City- and County . Building .. .. - - CITY. TOWN Salto 1*. LakeT 7 Cityoj*. STATE Utah REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey DATE 1959 .XFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Historic Sites _Survey , Park Service CITY. TOWN Washington , STATE D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -XEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED .—UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED AMOVED DATE **•*•*•1912 _FAIR _UNEXPOSED (log cabin) DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Temple Square is a ten acre block in Salt Lake City, the point from which all city streets are numbered. -

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

Temple Square Tours

National Association of Women Judges 2015 Annual Conference Salt Lake City, Utah Salt Lake City Temple Square Tours One step through the gates of Temple Square and you’ll be immersed in 35 acres of enchantment in the heart of Salt Lake City. Whether it’s the rich history, the gorgeous gardens and architecture, or the vivid art and culture that pulls you in, you’ll be sure to have an unforgettable experience. Temple Square was founded by Mormon pioneers in 1847 when they arrived in the Salt Lake Valley. Though it started from humble and laborious beginnings (the temple itself took 40 years to build), it has grown into Utah’s number one tourist attraction with over three million visitors per year. The grounds are open daily from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and admission is free, giving you the liberty to enjoy all that Temple Square has to offer. These five categories let you delve into your interests and determine what you want out of your visit to Temple Square: Family Adventure Temple Square is full of excitement for the whole family, from interactive exhibits and enthralling films, to the splash pads and shopping at City Creek Center across the street. FamilySearch Center South Visitors’ Center If you’re interested in learning about your family history but not sure where to start, the FamilySearch Center is the perfect place. Located in the lobby level of the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, the FamilySearch Center is designed for those just getting started. There are plenty -1- of volunteers to help you find what you need and walk you through the online programs. -

Alabama Governor's Office Robert Bentley State Capitol 600 Dexter Avenue Montgomery, Alabama 36130

Alabama Governor’s Office Robert Bentley State Capitol 600 Dexter Avenue Montgomery, Alabama 36130 http://governor.alabama.gov/contact/contact_form.aspx Arizona Governor’s Office The Honorable Janice K. Brewer Arizona Governor Executive Tower 1700 West Washington Street Phoenix, AZ 85007 http://www.azgovernor.gov/contact.asp California Governor’s Office Governor Jerry Brown c/o State Capitol, Suite 1173 Sacramento, CA 95814 http://gov.ca.gov/m_contact.php Colorado Governor’s Office John W Hickenlooper, Governor 136 State Capitol Denver, CO 80203-1792 http://www.colorado.gov/cs/Satellite/GovHickenlooper/CBON/124967424031 7 Delaware Governor’s Office Office of the Governor - Dover 150 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. South 2nd Floor Dover, DE 19901 https://governor.delaware.gov/locations.shtml Florida Governor’s Office Office of Governor Rick Scott State of Florida The Capitol 400 S. Monroe St. Tallahassee, FL 32399-0001 http://www.flgov.com/contact-gov-scott/email-the-governor/ Georgia Governor’s Office Office of the Governor Nathan Deal 206 Washington Street 111 State Capitol Atlanta, Georgia 30334 http://gov.georgia.gov/webform/contact-governor-domestic-form Hawaii Governor’s Office The Honorable Neil Abercrombie Governor, State of Hawai'i Executive Chambers, State Capitol Honolulu, Hawai'i 96813 Idaho Governor’s Office Office of the Governor State Capitol P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720 http://gov.idaho.gov/ourgov/contact.html Illinois Governor’s Office Office of the Governor 207 State House Springfield, IL 62706 http://www2.illinois.gov/gov/pages/contactthegovernor.aspx Indiana Governor’s Office Office of the Governor Statehouse Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2797 http://www.in.gov/gov/2333.htm Kansas Governor’s Office Governor Sam Brownback Capitol, 300 SW 10th Ave., Ste. -

Addresses for All State Governors

Addresses for all State Governors Powers of Governors: Governors, all of whom are popularly elected, serve as the chief executive officers of the fifty states and five commonwealths and territories. As state managers, governors are responsible for implementing state laws and overseeing the operation of the state executive branch. As state leaders, governors advance and pursue new and revised policies and programs using a variety of tools, among them executive orders, executive budgets, and legislative proposals and vetoes. Governors carry out their management and leadership responsibilities and objectives with the support and assistance of department and agency heads, many of whom they are empowered to appoint. A majority of governors have the authority to appoint state court judges as well, in most cases from a list of names submitted by a nominations committee. Although governors have many roles and responsibilities in common, the scope of gubernatorial power varies from state to state in accordance with state constitutions, legislation, and tradition, Veto Power All 50 state governors have the power to veto whole legislative measures. In a large majority of states a bill will become law unless it is vetoed by the governor within a specified number of days, which vary among states. In a smaller number of states, bills will die (pocket veto) unless they are formally signed by the governor, also within a specified number of days. Other types of vetoes available to the governors of some states include "line-item" (by which a governor can strike a general item from a piece of legislation), "reduction" (by which a governor can delete a budget item), and "amendatory" (by which a governor can revise legislation).