My Pessoa: Uncovering “The Others in Me”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pessoa's Names

JOHN FROW “A Nonexistent Coterie”: Pessoa’s Names A narrative begins at the end of a journey, at a place where “the sea ends and the earth begins. It is raining over the colorless city. The waters of the river are polluted with mud, the riverbanks flooded. A dark vessel, the Highland Brigade, ascends the somber river and is about to anchor at the quay of Alcântara.”1 A passenger disembarks, a certain Doctor Ricardo Reis, aged 48, born in Oporto and arriving from Rio de Janeiro, as we learn when he signs the register at the Hotel Bragança. He has returned to Lisbon after receiving a telegram from a fellow poet, Álvaro de Campos, informing him of the death of their friend Fernando Pessoa. Reading through the newspaper archives, Dr Reis finds an obituary that reports that Pessoa died “in silence, just as he had always lived,” and it adds that “[i]n his poetry he was not only Fernando Pessoa but also Álvaro de Campos, Alberto Caeiro, and Ricardo Reis. There you are,” the narrator continues, an error caused by not paying attention, by writing what one misheard, because we know very well that Ricardo Reis is this man who is reading the newspaper with his own open and living eyes, a doctor forty-eight years of age, one year older than Fernando Pessoa when his eyes were closed, eyes that were dead beyond a shadow of a doubt. No other proofs or testimonies are needed to verify that we are not dealing with the same person, and if there is anyone who is still in doubt, the narrator persists, let him go to the Hotel Bragança and check with the manager, a man of impeccable credentials (23-24). -

Rhyming Dictionary

Merriam-Webster's Rhyming Dictionary Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Springfield, Massachusetts A GENUINE MERRIAM-WEBSTER The name Webster alone is no guarantee of excellence. It is used by a number of publishers and may serve mainly to mislead an unwary buyer. Merriam-Webster™ is the name you should look for when you consider the purchase of dictionaries or other fine reference books. It carries the reputation of a company that has been publishing since 1831 and is your assurance of quality and authority. Copyright © 2002 by Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merriam-Webster's rhyming dictionary, p. cm. ISBN 0-87779-632-7 1. English language-Rhyme-Dictionaries. I. Title: Rhyming dictionary. II. Merriam-Webster, Inc. PE1519 .M47 2002 423'.l-dc21 2001052192 All rights reserved. No part of this book covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission of the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America 234RRD/H05040302 Explanatory Notes MERRIAM-WEBSTER's RHYMING DICTIONARY is a listing of words grouped according to the way they rhyme. The words are drawn from Merriam- Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Though many uncommon words can be found here, many highly technical or obscure words have been omitted, as have words whose only meanings are vulgar or offensive. Rhyming sound Words in this book are gathered into entries on the basis of their rhyming sound. The rhyming sound is the last part of the word, from the vowel sound in the last stressed syllable to the end of the word. -

Fernando Pessoa, Poet, Publisher, and Translator

FERNANDO PESSOA, POET, PUBLISHER, AND TRANSLATOR R. W. HOWES FERNANDO PESSOA is widely considered to be the greatest Portuguese poet of the twentieth century and a major writer of European stature. His enigmatic personality and the potent combination of poetic genius and metaphysics in his verse have fascinated a wide variety of readers both in Portugal and abroad. His invention of heteronyms, or alter egos, poets of his own creation who conducted a poetic 'drama in people', has found a response in the anxieties of the twentieth century, while the innovations in his poetic style, partly influenced by his fluency in English, have revolutionized modern Portuguese poetry. Pessoa published a relatively small proportion of his work during his lifetime, much of it in ephemeral periodical publications. He left behind a trunk full of manuscript poems and fragments of verse into which successive researchers have delved to produce a seemingly inexhaustible supply of'unpublished' writings. This has tended to divert attention from a detailed study of the works which he did publish while alive. ^ The British Library is fortunate to possess copies of all five of the volumes of Fernando Pessoa's verse which were published in his lifetime as well as some of the periodicals in which he published contributions, together with various other publications associated with him. These help to illuminate not only the bibliographical history of Pessoa as a poet but also his activities as a publisher and translator. They provide too an interesting illustration of the complex way in which a large research library's collections are built up, even where the works of a relatively modern author are concerned. -

Download Issue

www.literaryendeavour.org ISSN 0976-299X LITERARY ENDEAVOUR International Refereed / Peer-Reviewed Journal of English Language, Literature and Criticism UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 VOL. X NO. 1 JANUARY 2019 Chief Editor Dr. Ramesh Chougule Registered with the Registrar of Newspaper of India vide MAHENG/2010/35012 ISSN 0976-299X ISSN 0976-299X www.literaryendeavour.org LITERARY ENDEAVOUR UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 INDEXED IN GOOGLE SCHOLAR EBSCO PUBLISHING Owned, Printed and published by Sou. Bhagyashri Ramesh Chougule, At. Laxmi Niwas, House No. 26/1388, Behind N. P. School No. 18, Bhanunagar, Osmanabad, Maharashtra – 413501, India. LITERARY ENDEAVOUR ISSN 0976-299X A Quarterly International Refereed Journal of English Language, Literature and Criticism UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 VOL. X : NO. 1 : JANUARY, 2019 Editorial Board Editorial... Editor-in-Chief Writing in English literature is a global phenomenon. It represents Dr. Ramesh Chougule ideologies and cultures of the particular region. Different forms of literature Associate Professor & Head, Department of English, like drama, poetry, novel, non-fiction, short story etc. are used to express Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Sub-Campus, Osmanabad, Maharashtra, India one's impressions and experiences about the socio-politico-religio-cultural Co-Editor and economic happenings of the regions. The World War II brings vital Dr. S. Valliammai changes in the outlook of authors in the world. Nietzsche's declaration of Department of English, death of God and the appearance of writers like Edward Said, Michele Alagappa University, Karaikudi, TN, India Foucault, Homi Bhabha, and Derrida bring changes in the exact function of Members literature in moulding the human life. -

Encoding, Visualizing, and Generating Variation in Fernando Pessoa's

Encoding, Visualizing, and Generating Variation in Fernando Pessoa’s Livro do Desassossego Manuel Portela and António Rito Silva Abstract: One of the goals of the LdoD Digital Archive is to show Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet as a network of potential authorial intentions and a conjectural construction of its successive editors. Our digital repre- sentation of the dynamics of textual and bibliographical variation depends on both XML encoding of variation sites (deletions, additions, substitutions, etc.) and metatextual information concerning authorial and editorial witnesses (date, order, heteronym, etc.). While TEI-XML markup may be considered as a particular kind of critical apparatus on its own, it is through visualization tools and graphical interface that users will be able to engage critically with the dynamics of varia- tion in authorial and editorial witnesses. Besides representation of textual and bibliographical variation in the work’s genetic and edito- rial history, the LdoD Digital Archive will enable readers to generate new virtual forms of the work, assuming the roles of editor and/or author. Our paper discusses the theoretical and technical aspects of the various strategies adopted for encoding, visualizing, and generating variation in the LdoD Digital Archive. These issues are discussed with the support of a prototype currently under development. Keywords: Fernando Pessoa, digital archive, social edition, TEI-encoding, visual- ization, variants, variation Fernando Pessoa’s Livro do Desassossego (Book of Disquiet) is an unfinished book project.1 Pessoa wrote more than five hundred texts meant for this work between 1913 and 1935, the year of his 1 “Nenhum Problema Tem Solução: Um Arquivo Digital do Livro do Desas- sossego” [No Problem Has a Solution: A Digital Archive of the Book of Disquiet] is a research project of the Centre for Portuguese Literature at the University of Coimbra (2012‒2015), funded by FCT (Foundation for Science and Technology). -

The Lonesome Death of Bridget Furey Or: Pessoa Down Under

ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics Issue 17 October 2019 The Lonesome Death of Bridget Furey or: Pessoa Down Under Jack Ross The Dead this is the war I lost a woman versus three poets – Bridget Furey, ‘Brag Art’ (brief 7 (1997): 31) New Zealand poet Bridget Furey flickered into existence for a brief moment between the late 1980s and 1990s. Her contributor’s bio in Landfall 168 (1988), describes her as ‘22 years of age. Recently returned from an extended working holiday overseas; presently living and working in Dunedin.’ That would put her date of birth sometime around 1966. Her next, and final, contributor note, in A Brief Description of the Whole World 7 (1997), says simply: ‘Bridget Furey has just returned to Dunedin after a stint overseas.’ (brief 56) The rest, it would appear, is silence. In her brief period in the limelight, Furey contributed three poems – ‘Ricetta per Critica,’ ‘The Idea of Anthropology on George Street,’ and ‘The Book-Keepings of a Ternary Mind in Late February’ – to our most celebrated literary periodical, Landfall. And another, ‘Brag Art,’ which must now be regarded as her swansong, to its antithesis, the avant-garde quarterly A Brief Description of the Whole World. Out of curiosity, I spent some time recently trying to track down an image of Bridget Furey. I drew a blank in the local repositories, but the photograph opposite, taken by Alen MacWeeney and dated ‘Loughrea, 1966,’ though clearly not of the poet herself (unless she was unusually prone to concealing information about her age) may come, perhaps, from some cognate branch of the family? Loughrea is in County Galway, Ireland. -

A a Posteriori a Priori Aachener Förderdiagnostische Abbild

WSK-Gesamtlemmaliste (Stand: Januar 2017) A abgeleitetes Adverb Abklatsch a posteriori abgeleitetes Nominal Abkürzung a priori abgeleitetes Verb Abkürzungsprozess Aachener abgeleitetes Wort Abkürzungspunkt Förderdiagnostische abgerüstete Abkürzungsschrift Abbild Transliterationsvariante Abkürzungswort Abbildtheorie abgeschlossene Kategorie Ablativ Abbildung Abgeschlossenheit Ablativ, absoluter Abbildung, Beschränkung Abglitt einer ablative Abgraph Abbildung, Bild einer ablative case Abgrenzungssignal Abbildung, konzeptuelle ablativus absolutus abhängige Prädikation Abbildung-1 ablativus causae abhängige Rede Abbildungen, ablativus comitativus abhängige Struktur Komposition von ablativus comparationis abhängiger Fragesatz Abbildungsfunktion ablativus copiae abhängiger Hauptsatz Abbildungstheorie ablativus discriminis abhängiger Satz Abbreviation ablativus instrumenti abhängiges Morphem abbreviatory convention ablativus limitationis Abhängigkeit Abbreviatur ablativus loci Abhängigkeit, entfernte Abbreviaturschrift ablativus mensurae Abhängigkeit, funktionale Abbruchpause ablativus modi Abbruchsignal Abhängigkeit, gegenseitige ablativus originis Abc Abhängigkeit, kodierte ablativus pretii Abdeckung Abhängigkeit, ablativus qualitatis Abduktion konzeptuelle ablativus respectus Abecedarium Abhängigkeit, ablativus separativus sequenzielle abessive ablativus sociativus Abhängigkeitsbaum A-Bewegung ablativus temporis Abhängigkeitsgrammatik Abfolge Ablaut Abhängigkeitshypothese Abfolge, markierte Ablaut, qualitativer ability abfragen Ablaut, quantitativer -

THE ULTIMATE HOMONYM GROUP HEY Dingl HI Ghizit~ HIE Dingr HOE Dian HY Dingh; HY- Bush; DMITRI A

224 HEI Rheirr THE ULTIMATE HOMONYM GROUP HEY dingl HI ghizit~ HIE dingr HOE dian HY dingh; HY- bush; DMITRI A. BORGMANN 1 police Dayton, Washington 1- quasi IA Virgin Two or more words spelled differently but pronounced the same 1E brief are called homonyms by logologists. Today I slinguistics appears 1EH Diehl to have no name for such words homonyms, homophones, and 1EU Nieu\\ homographs mayor even must all be spelled and sounded alike. IG chigno Exemplifying logological homonyms at their best are the word IGH Denbi groups RIGHT, RITE, WRIGHT, and RITE; MAIN, MAINE, MANE, IGHT Kirk and MESNE; and RHODE (as in "Rhode 1sland"), ROAD, RODE, ROED, IH ihleite and ROW ED. Larger homonym groups exist (the group ineluding 11 lizuka AIR and HEIR, for instance), but these invariably include aestheti 1] Ljubijc cally unattractive words or names. Even if we accept the object ILL tortil ionable members of the larger groups, no such group ineludes 15 debris more than 10 or 12 words and/or names. 1T esprit 1X Grand To overcome this severe limitation, the dedicated homonymist IX Oktyat turns to letter homonym groups; letters and letter combinations ]0 sjomil representing one specific sound. In this realm, much larger homo nym groups are possible. The largest such group heretofore identi My choic~ fied is the group consisting of representations of the final vowel E is the sound in WORDPLAY. According to a note in the May 1979 Colloquy chance of in Word Ways, Richard Lederer has found 34 ways in which that long sound sound is represented in English. -

Ghostspeaking: Heteronyms and the Translation of Poetry

Ghostspeaking: Heteronyms and the Translation of Poetry Peter Anthony Boyle Doctor of Creative Arts 2017 Western Sydney University Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Chris Andrews for his patient, insightful, generous and encouraging support throughout the research and writing process. His willingness to read carefully though many drafts and make helpful suggestions has been invaluable in the completion of this project. Special thanks are also due to the Writing and Society Research Centre at Western Sydney University. The Centre's friendly collegiate atmosphere and stimulating discussions and seminars were of great value in developing my ideas. My special thanks are due to Professor Ivor Indyk for his support. I would also like to thank the always helpful Research Support staff, Melinda Jewell and Suzanne Gapps, for their assistance in many administrative matters. Western Sydney University provided generous financial assistance to enable me to attend the 2016 Festival de Poesía Amada Libertad in El Salvador. I would like to acknowledge and thank the organisers of this Festival and of other Festivals I have attended over several years: the Medellín Poetry Festival (1997), the Festival franco-anglais de poésie (1999), the Caracas Poetry Festival (2005), the Struga International Poetry Festival (2009), the Poetry Festival of Granada Nicaragua (2013) and the Trois Rivières Festival (2013). Through the exposure to new writing and the personal contacts and exchanges they offer, these festivals have greatly furthered my development as a poet and a translator. My attendance at several of these festivals was made possible by assistance from the Australia Council of the Arts. I would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of many in the poetry community: Luke Fischer and Dalia Nassar in whose Poetry Salon several of the poems in Ghostspeaking were first presented to the public; Judith Beveridge, David Brooks, M.T.C. -

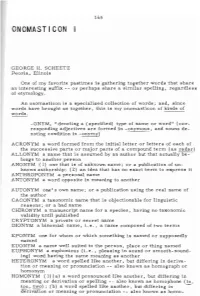

Onomasticon Is a Specialized Collection of Words; And, Since Words Have Brought Us Together, This Is My Onomasticon of Kinds of 5 Yield Web 3 Words

165 ehead ONOMASTICON ,hen it be RUN ABOUT alphabetical .de s to GEORGE H. SCHEETZ (e.g. J HOW Peoria, illinois Ie stion to a an ?" One of my favorite pastime s is gathering togethe r words that share an interesting suffix -- or perhaps share a similar spelling, regardless 5, all in Web of etymology. rom the An onomasticon is a specialized collection of words; and, since words have brought us together, this is my onomasticon of kinds of 5 yield Web 3 words. dment yields -ONYM, 11 denoting a (specified) type of name or word'1 (cor responding adjectives are formed in -onymous, and nouns de )VINCE, noting condition in -onymy) eIetion CRONE, ACRONYM a word formed from the initial letter or letters of each of the successive parts or major parts of a compound term (as radar) ALLONYM a name that is assumed by an author but that actually be OFF, longs to another person me for cur ANONYM (1) one that is of unknown name; or a publication of un t...FFRON known authorship; (2) an idea that has no exact term to express it me of a ANTHROPONYM a peJ;'sonal name ANTONYM a word opposite in meaning to another ,TELE, A UTONYM o~ I s own name; or a publication using the re al name of 3; may be the author L, ST, TE, CACONYM a taxonomic name that is objectionable for linguistic reasons; or a bad name CHIRONYM a manuscript name for a species, having no taxonomic c... (in Web 3) validity until publisbed CRYPTONYM a private or secret name onants and DIONYM a binomial name, 1. -

WSK-Gesamtlemmaliste (Stand: Mai 2017)

WSK-Gesamtlemmaliste (Stand: Mai 2017) A abgeleitetes Verb Ablativ a posteriori abgeleitetes Wort Ablativ, absoluter a priori abgerüstete ablative Transliterationsvariante Aachener Förderdiagnostische ablative case abgeschlossene Kategorie Abbild ablativus absolutus Abgeschlossenheit Abbildtheorie ablativus causae Abglitt Abbildung ablativus comitativus Abgraph Abbildung, Beschränkung ablativus comparationis einer Abgrenzungssignal ablativus copiae Abbildung, Bild einer abhängige Prädikation ablativus discriminis Abbildung, konzeptuelle abhängige Rede ablativus instrumenti Abbildung-1 abhängige Struktur ablativus limitationis Abbildungen, Komposition abhängiger Fragesatz von ablativus loci abhängiger Hauptsatz Abbildungsfunktion ablativus mensurae abhängiger Satz Abbildungstheorie ablativus modi abhängiges Morphem Abbreviation ablativus originis Abhängigkeit abbreviatory convention ablativus pretii Abhängigkeit, entfernte Abbreviatur ablativus qualitatis Abhängigkeit, funktionale Abbreviaturschrift ablativus respectus Abhängigkeit, gegenseitige Abbruchpause ablativus separativus Abhängigkeit, kodierte Abbruchsignal ablativus sociativus Abhängigkeit, konzeptuelle Abc ablativus temporis Abhängigkeit, sequenzielle Abdeckung Ablaut Abhängigkeitsbaum Abduktion Ablaut, qualitativer Abhängigkeitsgrammatik Abecedarium Ablaut, quantitativer Abhängigkeitshypothese abessive Ablautausgleich ability A-Bewegung Ablautbildung Abjad Abfolge Ablautdoppelung Abklatsch Abfolge, markierte Ablautkombination Abkürzung abfragen Ablautreihe Abkürzungsprozess -

The Mask in Verse. Imaginary Poets and Their Autobiographical Poetry (Jan Wagner, Die Eulenhasser in Den Hallenhäusern)

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF LIFE WRITING VOLUME X (2021) SV13–SV32 The Mask in Verse. Imaginary Poets and Their Autobiographical Poetry (Jan Wagner, Die Eulenhasser in den Hallenhäusern) Jutta Müller-Tamm Freie Universität Berlin Abstract This article examines German poet Jan Wagner’s Die Eulenhasser in den Hallenhäusern [The Owl Haters in the Hall Houses] (2012) and the effects of fictional authorship with respect to autobiographical poetry. Wagner's fiction of three poets—their lives and their poems—proves to be an artfully ambivalent construction: on the one hand, the link between persona and poetic voice seems to be undeniably given, while on the other hand, the autobiographical impact of the poems appears to be an effect of the reader’s desire and his or her response to the work. Wagner’s text exploits, confirms and, at the same time, challenges the desire to read poetry as autobiographical expression. Keywords: Autobiographical Poetry, Heteronyms, Jan Wagner, Fernando Pessoa Zusammenfassung Dieser Artikel untersucht den Band Die Eulenhasser in den Hallenhäusern (2012) des deutschen Lyrikers Jan Wagner im Hinblick auf den autobiographischen Charakter fiktionaler Autorschaft. Wagners Erfindung von drei Dichtern und ihrer – offenkundig mit ihrem Leben verwobenen – Lyrik erweist sich als kunstvoll ambivalente Konstruktion: Einerseits wird die Verbindung zwischen Persona und Copyright © 2021 Jutta Müller-Tamm https://doi.org/10.21827/ejlw.10.37637 This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Jutta Müller-Tamm – The Mask in Verse. Imaginary Poets and Their Autobiographical Poetry 14 poetischer Stimme ausgestellt, andererseits wird die Verbindung zwischen Dichtung und Leben als Leküreeffekt gekennzeichnet.